Tom Stewart, Head of History at Maiden Erlegh School, sets out tangible strategies that he and his department take when challenging more able students in history lessons.

History at secondary school level is a subject that, from my experience, is usually taught in mixed ability classes. Due to this, and to rightfully ensure the progress of those who struggle with literacy and require further support, lessons can tend to be pitched towards the middle with scaffolding and structure in place to help those struggling. The potential problem with this approach is that it risks neglecting the more able students and those who need to be challenged or stretched (or whichever phrase is used in your setting), to reach their potential. I hope this blog post will give you some ideas to take away to challenge the more able learners in your history lessons.

#1. Short-term: Questioning

A simple and easy way to challenge those more able students is through effective use of the questioning they face in a lesson. I imagine most teachers know about open and closed questions and how the latter can limit students to a one-word answer, whilst the former can require students to elaborate in more depth. Therefore, the answer the students give can often depend on how much thought has gone into the question asked.

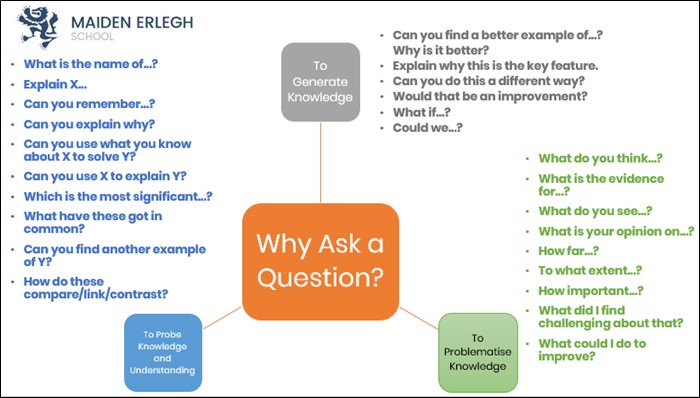

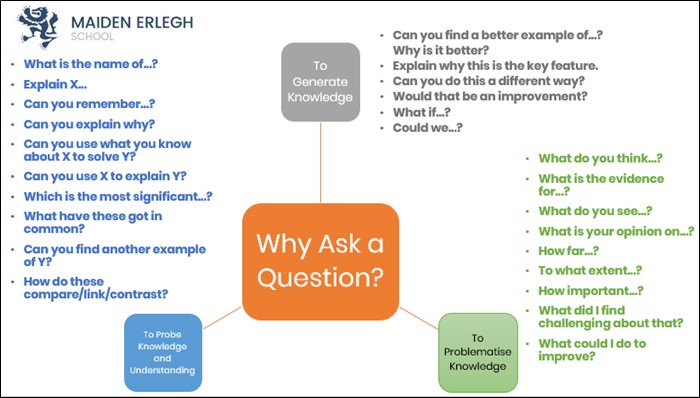

It is important to consider why a teacher is asking a question and this can then be applied to challenging the more able students by asking a variety of questions for different reasons. In a recent CPD session at my school, delivered by two excellent Assistant Headteachers, Rob Buck and Ben Garner, this principle, with some examples, was shared with staff (Figure 1). It reminded myself and my department to think carefully about the questioning we carried out and to target those more able students, whether they be in Year 7, Year 10 or Year 13.

Figure 1

#2. Medium-term: Widen their perspectives

More able students are often characterised by a curious and inquisitive nature. To support this, it is important to not be overly selective with the history shared with students, but find opportunities to reveal more of the story. Students of all abilities enjoy learning knowledge that isn’t necessarily vital to the topic – knowledge that Bailey-Watson calls ‘hinterland’ knowledge – and we should be willing to share with students more of the big picture in order to widen their perspectives and improve their historical thinking.

Homework can be an outlet for this; the previously mentioned Bailey-Watson and Kennet launched their ‘meanwhile, elsewhere…’ project (Figure 2) with the explicit intention of ‘expanding historical horizons’. Used effectively, this is a strategy that challenges the more able students to make those links between what they know and what they are yet to know.

Figure 2

#3. Long-term: Enquiry-based topics

History lends itself to a wealth of interesting topics. This selection narrows at GCSE and A-Level as specifications force middle leaders to select one topic and not another. However, at Key Stage 3, there is normally more choice and also an opportunity to challenge more able students. We have found evolving already-established topics – or creating new ones where time allowed and necessity demanded – into enquiry-based ones supports more able students by forcing them to ‘think hard’.

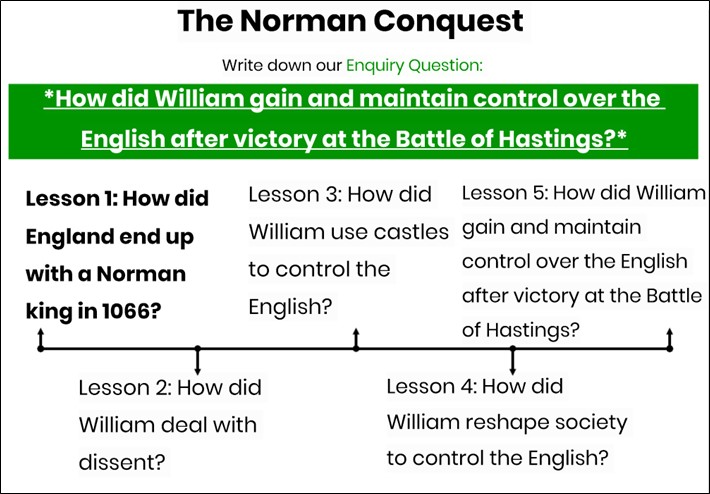

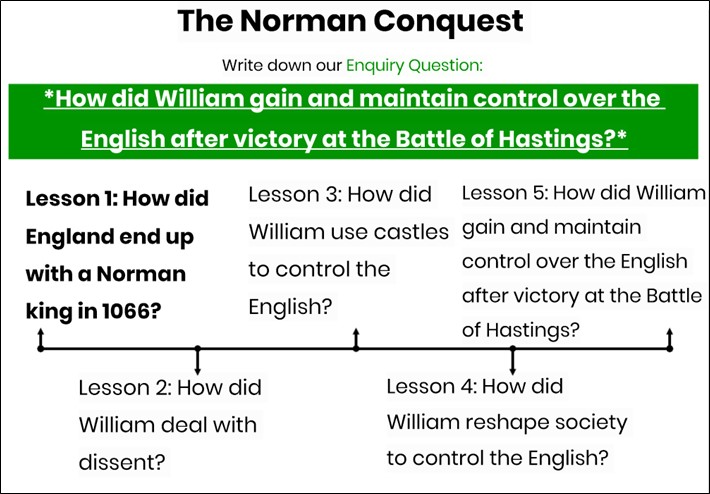

Our topic on the Norman Conquest, an event described by Peter Rex as ‘the single most important event in English history’ avoids a simpler narrative of events and instead forces students, especially the more able, to consider how King William managed not only to gain control but maintain it after the Battle of Hastings (Figure 3). This topic was designed by my fantastic colleague, Chloe Bateman, and this approach provides all students with an overview of where the lesson and topic fits in and also encourages deep thinking about the answer to the enquiry question before it has even been covered.

Combined with sharing demanding texts with students in lessons and homework that relates directly to the enquiry question, whilst extending their knowledge and understanding even further, enquiry-based topics can prove very effective at challenging more able students in secondary history.

Figure 3

There are plenty of strategies out there and there are more that I use and could have shared with you, but here are three that you could look to introduce to your setting. The important point is to be mindful about the experience more able students get in our classrooms. Do they feel challenged? Would you in their shoes? If not, then be active in doing something about it.

References

- Bailey-Watson, W. and Kennett, R. (2019). '"Meanwhile, elsewhere…": Harnessing the power of community to expand students’ historical horizons’, Teaching History, 176.

- https://meanwhileelsewhereinhistory.wordpress.com/

- Paramore, J. (2017). Questioning to Stimulate Dialogue, in Paige R., Lambert, S. and Geeson, R. (eds), Building Skills for Effective Primary Teaching, London: Learning Matters.

- Rex, P. (2011). 1066: A New History of the Norman Conquest, Amberley Publishing.

Read more: