Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 January 2021

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Associate and co-author of NACE’s new publication “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”.

To group or not to group: that is the question…

The organisation and management of cognitively challenging learning environments is one of three focus areas highlighted in NACE’s new research publication, “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”, which marks the first phase in our “Making Space for Able Learners” project. Developed in partnership with NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools, the research examines the impact of cognitive challenge in current school practice against a backdrop of relevant research.

As teachers, we aim to provide a cognitively challenging learning environment for our more able and exceptionally able pupils, which is beneficial to them. The organisational decisions surrounding this should therefore optimise opportunities for learning. Teachers and school leaders must not only consider content to be studied, but also the impact of classroom management decisions from the perspective of the learner. The NACE research showed that these classroom management and organisational decisions were one of three key factors impacting on cognitively challenging learning, alongside curriculum organisation and design and the use of rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse.

One aspect of managing cognitively challenging learning environments is any choice relating to mixed ability teaching versus a variety of designs for selection and grouping by ability. Within the classroom the teacher also balances demands to provide opportunities for all, while simultaneously identifying the nature and opportunity for challenge.

Does ability grouping benefit learners?

There is a paucity of strong evidence that ability grouping is beneficial to academic outcomes for all. However, Parsons and Hallam (2014) did find that grouping can benefit more able pupils. This benefit is not necessarily associated with the act of setting, but with the quality of teaching provided for these groups. Pupils also have opportunities to work at a faster pace, but against this aspiration, Boaler et al. (2000) found pace incompatible with understanding for many pupils. Regardless of the choice made to group or not to group, there is a need to reflect on whether teaching is homogenous or designed to meet the needs of the pupils. Often the weakness is the assumption that grouping alone will drive the learning experience, without an understanding of the cognitive and emotional impact this has on the pupils themselves.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has examined the use of setting and streaming, which are usually related to attainment rather than ability, and has found that there is often a small negative impact for disadvantaged pupils and lower abilities. When designing learner groupings, it is important to be aware of the impact for all learners and create a beneficial model for all.

How should teachers and schools approach ability grouping?

First, decide what you hope to teach and what it is pupils have the potential to achieve, given enough learning opportunities. Remember, learning is not limited to reproducing planned content by rote, but instead its success lies within a growth of knowledge, its complexity, and its application. Pupils bring a wide range of prior learning, knowledge and experiences which they can share with each other and use to construct new schema. In a well-designed learning environment, pupils have the potential to develop their knowledge, skills and understanding beyond the delivered content. Young et al. (2014) demonstrate the importance of powerful knowledge which takes pupils beyond their own experiences. The development of metacognition and exposure to wider experience should therefore be included in decisions related to the organisation of groups and lesson planning.

Second, decide what environment will provide the best learning experience for the pupils.

- Is it best to present advanced curricula at an accelerated rate?

- Does teaching include multiple high-order thinking models and skills?

- Is learning pupil-centred?

- Are multiple modality enquiry methods in play?

- Will grouping take account of the complexity of ability and enhance its manifestation?

- Will pupils benefit from a wide range of perspectives?

- Will pupils utilise the learning experiences of others to reflect upon and refine their own learning?

The answers to these questions will help teachers to make decisions regarding the nature of grouping and classroom organisation. The choice of model should be one which most benefits the learner, one which is not driven by systemic organisational requirements, and one which recognises the impact of external factors on perceived ability.

Finally, what models are available and how can cognitive challenge be achieved within them?

- Mixed ability grouping has the benefit of exposing pupils to the wider knowledge, background, and experience of others. In these environments, problems with different layers of complexity and multiple learning routes are often used. The big question or cognitively challenging proposition often promotes the learning with supporting systems and prompts in place for those challenged by the learning.

- Cutaway models are an alternative to the simpler mixed ability model. In the cutaway approach, the teacher constantly assesses pupils’ learning and needs and directs their learning to maximise opportunities, growth, and development. Pupils join and leave the shared learning (“cutting away” as appropriate), based on prior learning and their response to the existing task. This model develops and utilises independence and metacognition.

- Grouping by task is often used when it is possible to create smaller groups working on different tasks within the same classroom. The teacher uses very specific knowledge relating to pupils’ prior learning and abilities to organise the classroom groups. The teacher can therefore target the teaching to respond to more specific learning opportunities, which in turn can increase pupils’ enjoyment and engagement in their learning.

- Grouping by subject is an extension of grouping by task. If pupils learn all their subjects within the same class group, this enables the teacher to note the different strengths within the subject. In larger schools, pupils are often grouped by overall performance in specific subjects. This model might include advanced curriculum and require higher-order thinking skills. Pupils might be given opportunities to research more deeply into areas of interest. For this model to be successful there needs to be fluidity between the groups so that pupils are well-placed to enjoy cognitively challenging experiences.

With these ideas in mind, schools will then create an overarching model which reflects the school vision, ethos and culture. Teachers will consistently strive to provide cognitively challenging learning opportunities which benefit all. They use their knowledge of the pupils’ past and present learning and their vision of what the pupils can be and can achieve in the future to design the learning environment. They then organise the classroom to excite, engage and challenge their pupils – remembering that regardless of the sophistication of the approach, every group will be mixed ability as no two pupils are identical. If high-quality and engaging teaching is child-centred and not homogenous, then pupils will excel in cognitively challenging classrooms.

References

- Boaler, J., Wiliam, D. and Brown, M. (2000). Students’ experiences of ability grouping – disaffection, polarisation and the construction of failure. British Education Research Journal, 26 (5), 631–648.

- Education Endowment Foundation, Teaching and Learning Toolkit

- Parsons, S. and Hallam, S. (2014). The impact of streaming on attainment at age seven: evidence from the Millennium Cohort Study. The Oxford Review of Education, 40 (5), 567-589.

- VanTassel-Baska, J. and Brown, E. (2007) Toward Best Practice: An analysis of the efficacy of curriculum models in gifted education. Gifted Child Quarterly, 52, 342.

- Young, M and Muller, J. (2013). On the Powers of Powerful Knowledge. Review of Education1(3) 229-250.

Additional reading and support

Share your views

How do you use ability grouping, and why? Share your experiences by commenting on this blog post or by contacting communications@nace.co.uk

Tags:

cognitive challenge

CPD

differentiation

grouping

leadership

pedagogy

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

17 November 2020

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Associate and co-author of NACE’s new publication “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”.

When you’re planning a lesson, are your first thoughts about content, resources and activities, or do you begin by thinking about learning and cognitive challenge? How often do you consider lessons from the viewpoint of your more able pupils? Highly able pupils often seek out cognitively challenging work and can become distressed or disengaged if they are set tasks which are constantly too easy.

NACE’s new research publication, “ Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”, marks the first phase in our “Making Space for Able Learners” project. Developed in partnership with NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools, the research examines the impact of cognitive challenge in current school practice against a backdrop of relevant research. What do we mean by ‘cognitive challenge’?

Cognitive challenge can be summarised as an approach to curriculum and pedagogy which focuses on optimising the engagement, learning and achievement of highly able children. The term is used by NACE to describe how learners become able to understand and form complex and abstract ideas and solve problems. Cognitive challenge prompts and stimulates extended and strategic thinking, as well as analytical and evaluative processes.

To provide highly able pupils with the degree of challenge that will allow them to flourish, we need to build our planning and practice on a solid foundation.

This involves understanding both the nature of our pupils as learners and the learning opportunities we’re providing. When we use “challenge” as a routine, learning will be extended at specific times on specific topics – which has useful but limited benefit. However, by strategically building cognitive challenge into your teaching, pupils’ learning expertise, their appetite for learning and their wellbeing will all improve.

What does this look like in practice?

The research identified three core areas:

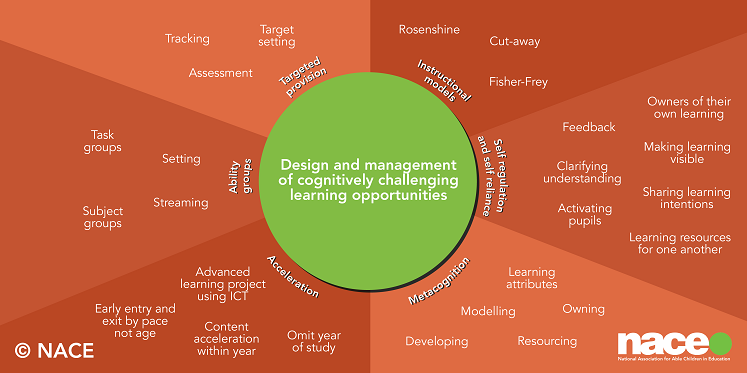

1. Design and management of cognitively challenging learning opportunities

In the most successful “cognitive challenge” schools, leaders have a clear vision and ambition for pupils, which explicitly reflects an understanding of teaching more able pupils in different contexts and the wider benefits of this for all pupils. This vision is implemented consistently across the school. All teachers engage with the culture and promote it in their own classrooms, involving pupils in their own learning. When you walk into any classroom in the school, pupils are working to the same model and expectation, with a shared understanding of what they need to do.

Pupils are able to take control of their learning and become more self-regulatory in their behaviours and increasingly autonomous in their learning. Through intentional and well-planned management of teaching and learning, children move from being recipients in the learning environment to effective learners who can call on the resources and challenges presented. They understand more about their own learning and develop their curiosity and creativity by extending and deepening their understanding and knowledge.

2. Rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse to support cognitive challenge

The importance of questions and questioning in effective learning is well understood, but the importance of depth and complexity of questioning is perhaps less so. When you plan purposeful, stimulating and probing questions, it gives pupils the freedom to develop their thought processes and challenge, engage and deepen their understanding. Initially the teacher may ask questions, but through modelling high-order questioning techniques, pupils in turn can ask questions which expose new ways of thinking.

This so-called “dialogic teaching” frames teaching and learning within the perspective of pupils and enhances learning by encouraging children to develop their thinking and use their understanding to support their learning. Initially, pupils might use the knowledge the teacher has given them, but when they’re shown how to use classroom discourse effectively, they’ll start to work alone, with others or with the teacher to extend their repertoire.

By using an enquiry-orientated approach, you can more actively engage children in the production of meaning and acquisition of new knowledge and your classroom will become a more interactive and language-rich learning domain where children can increase their fluency, retrieval and application of knowledge.

3. Curriculum organisation and design

How can you ensure your curriculum is organised to allow cognitive challenge for more able pupils? You need to consider:

- What is planned for the students

- What is delivered to the students

- What the students experience

Schools with a high-quality curriculum for cognitive challenge use agreed teaching approaches and a whole-school model for teaching and learning. Teachers expertly and consistently utilise key features relating to learning preferences, knowledge acquisition and memory.

Planning a curriculum for more able pupils means providing a clear direction for their learning journey. It’s necessary to think beyond individual subjects, assessment systems, pedagogy and extracurricular opportunities, and to look more deeply at the ways in which these link together for the benefit of your pupils. If teachers can understand and deliver this curriculum using their subject knowledge and pedagogical skills, and if your school can successfully make learning visible to pupils, you’ll be able to move from well-practised routines to highly successful and challenging learning experiences.

Taking it further…

If we’re going to move beyond the traditional monologic and didactic models of teaching, we need to recast the role of teacher as a facilitator of learning within a supportive learning environment. For more able pupils this can be taken a step further. If you can build cognitive challenge into your curriculum and the way you manage learning, and support this with a language-rich classroom, the entire nature of teaching and learning can change. Your highly able pupils will become increasingly autonomous and more self-reliant. They’ll become masters of their learning as they gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter. You can then extend your role even further, from learning facilitator to “learner activator”.

This blog post is based on an article originally written for and published by Teach Primary magazine – read the full version here.

Additional reading and support:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

independent learning

metacognition

mindset

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

questioning

research

student voice

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By York St John University,

20 October 2020

|

NACE is collaborating with York St John University on research and resources to help schools support more able learners with higher levels of perfectionism. In this blog post, the university’s Laura C. Fenwick, Marianne E. Etherson and Professor Andrew P. Hill explain how some classrooms are more perfectionistic than others and how reducing the degree to which classrooms are perfectionistic can help enhance learning and maintain student wellbeing.

Research suggests that more able learners are typically more perfectionistic than their classmates. Accordingly, more able learners place great demands on themselves to achieve unrealistic standards and respond with harsh self-criticism when their standards go unmet. However, more recently researchers have begun to explore the idea that perfectionism may not solely be an individual problem. Instead, environments such as the classroom have perfectionistic qualities that can both increase levels of perfectionism among those in the environment as well as having a detrimental impact on everyone in the environment regardless of their personal level of perfectionism. This is of concern as perfectionistic environments are likely to hinder learners’ capacity to thrive, and contribute to a range of negative outcomes, such as greater stress and poorer wellbeing.

A perfectionistic environment (or “perfectionistic climate”) refers to cues and messages that promote the view that performances (e.g. grades) must be perfect and less than perfect performances are unacceptable. The cues and messages are created by important social agents such as teachers, coaches and parents, and can be communicated both intentionally as well as inadvertently. In the classroom, the teacher is likely to be the main source of this information; in particular, though the language that is used, how tasks are structured, and the strategies used to reward or sanction student behaviour. Fortunately, teachers also have the potential to help reduce how perfectionistic the classroom is by purposefully avoiding certain cues and messages and promoting others. Here, we identify key components of a perfectionistic classroom and provide alternative strategies aimed at reducing the likelihood that the classroom is experienced as being perfectionistic by students.

Unrealistic expectations

Perfectionistic classrooms include expectations that are unrealistic and never lowered. The expectations are uniformly applied and do not account for the individual ability of the learner, their personal progress, or individual circumstances.

Key takeaways: In most classrooms, it is likely that learners will know what is expected of them in terms of behaviours and grades. However, what is most important about these targets and expectations is that they are realistic and adaptable for each learner. Standards that are personally challenging and lie within reach with concerted effort are the most optimally motivating and offer the greatest development opportunity for students.

Frequent or excessive criticism

Frequent or excessive criticism is also a feature of a perfectionistic classroom. This can include a focus on minor and inconsequential mistakes or an undue emphasis on the need to get everything “just right”.

Key takeaways: Avoid pointing out unimportant mistakes and focusing on errors when work reflects a student’s best effort or shows progress. Remedial feedback is obviously necessary, but the language used is important. Effective feedback focuses on the quality of the work, not the qualities of the learner (“this aspect of the work can be improved” versus “you have made a mistake here”). Ensure that positives are highlighted and reinforced before offering critical comments, especially for more perfectionistic students.

Problematic use of rewards and sanctions

The use of rewards and sanctions are common and powerful motivational tools in the classroom but when used to create feelings of shame or guilt, they can become problematic. Public displays of reward or sanction are best avoided because they promote these types of coercive emotions and encourage social comparison as opposed to a focus on personal development. Withdrawal of recognition and appreciation based on performance, for example, also reinforces the view that personal value comes solely from recognition and achievement.

Key takeaways: It is difficult to avoid the use of rewards and sanctions, but where possible these need to be provided privately. For rewards, focus on behaviours (e.g. effort) rather than innate qualities and for sanctions, encourage a sense of personal ownership and agency in proposed repreparation. Ultimately, it is important that students feel liked and valued regardless of their performances and behaviour, good or bad.

Anxiousness or preoccupation with mistakes

One final aspect of a perfectionistic classroom is anxiousness or preoccupation with mistakes. Risk taking is avoided and failure is discouraged.

Key takeaways: Mistakes (even big ones) need to be normalised in the classroom. A strong focus on creativity, problem-solving, and opportunities for learning through “trial and error” will instil a more resilient mindset and counterbalance undue apprehension regarding mistakes.

Summary

The concept of perfectionistic environments emphasises the need for more purposeful construction of the classroom. In being mindful of each of the issues above, and better monitoring and changing the cues and messages provided in the classroom, we believe teachers can alter the degree to which the environment is experienced as perfectionistic by students. In addition, in doing so, this will help reduce perfectionism and its negative effects among all students and be especially useful and important for more able and talented students who are more prone to the problems associated with perfectionism.

References

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 456-470.

Hill, A. P., & Grugan, M. (2020). Introducing perfectionistic climate. Perspectives on Early Childhood Psychology and Education, 4, 263-276.

Stricker, J., Buecker, S., Schneider, M., & Preckel, F. (2020). Intellectual giftedness and multidimensional perfectionism: A meta-analytic review. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 391-414.

Read more:

Join the conversation… York St John University’s Professor Andrew P. Hill will lead a keynote session on 17 November 2020 as part of the NACE Leadership Conference, exploring current research on perfectionism and more able learners, and how schools can create learning environments that reduce perfectionistic thinking. View the full conference programme.

Tags:

confidence

creativity

feedback

mindset

motivation

perfectionism

research

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Marianne Etherson,

11 May 2020

|

NACE is collaborating with York St John University on research and resources to help schools support more able learners with high levels of perfectionism. In this blog post, the university’s Marianne E. Etherson and Prof. Andrew P. Hill outline the importance of the need to “matter” in perfectionistic students and how we can begin to promote a sense of mattering in the classroom.

More able learners are typically bright, talented and ambitious. They possess innate aptitude and ability, but with it comes an intense pressure to succeed. Stemming from these intense pressures, students are highly motivated to demonstrate their talents, to fulfil expectations, and to reach their potential. And subsequently, many place irrational importance on their academic achievements. But when expectations become impossibly high, the pressure of being highly able will take an emotional toll. Indeed, because of their ability, more able learners often base their sense of self on their academic achievements. In the face of failure and setbacks, they may begin to question their worth, and as a result, many fall victim to psychological ill-being, lower self-esteem, and lower perceptions of mattering to others.

To matter to others is fundamental to building health and resilience. And a perceived sense of mattering is instrumental to protect against failures and setbacks. Mattering is defined as the feeling that others depend on us, are interested in us, and are concerned with our fate. Researchers have also begun to examine the idea of anti-mattering. Anti-mattering fundamentally differs from low perceptions of mattering as it includes feeling insignificant and marginalised by others. Research suggests that perceptions of anti-mattering can adversely impact psychological wellbeing. Anti-mattering, for instance, is associated with lower self-esteem and increased risk of depression and anxiety. Indeed, feelings of anti-mattering may also adversely impact student achievement and behaviour. For these reasons, it is important to examine personality traits that may influence perceptions of mattering and anti-mattering. One such trait is perfectionism.

Perfectionism is a particularly pervasive characteristic among the more able. Researchers define perfectionism as a personality trait by which individuals set irrational standards and engage in harsh self-criticism. Underpinning their incessant striving for achievement is a need to attain validation, approval, and a need to matter. Accordingly, perfectionistic individuals will be driven to attain expectations because they believe that only when expectations (e.g. grades) are met, they will be of worth and will matter to people who matter to them. Those high in anti-mattering may also catastrophise and overgeneralise their thoughts to perceive they do not matter at all and will not matter in the future. The profound need to matter can be intensified when unmet and thus, many will continue to strive relentlessly to counteract feelings of inferiority.

Because of its importance, people have begun to explore ways of boosting students’ sense of mattering. Mattering is indeed central to promoting healthy and positive development in schools. Ideally, a focus on mattering should be adopted as a whole-school approach, including all aspects of the school community. However, learning environments can act as focal points, to reinforce key messages to students (e.g. you are worthy, and you matter). Environments, such as the classroom, can also be designed to convey a sense of mattering, in addition to minimising external pressures. Teachers, certainly, play a prominent role in boosting learners’ sense of mattering. To convey a sense of interest and care for students, for instance, may be enough to transform students’ academic self-concept (i.e. how they think about, evaluate, or perceive themselves) and sense of what they can achieve.

Research examining school-based interventions shows promise in developing young people’s resilience and self-worth, which can act as protective factors against academic setbacks and interpersonal stress. This work provides a strong indication of the potential value of interventions that focus specifically on mattering. However, interventions focusing on mattering are still in development stages. Similarly, so are interventions that embed mattering and perfectionism. With this in mind, we (York St John University) are collaborating with NACE to pilot an intervention for more able learners aimed at increasing knowledge of perfectionism that includes elements of mattering and other key aspects of making perfectionism less harmful, such as self-compassion. Early indication is that informative videos are sufficient to increase awareness of perfectionism and we hope to learn more about the benefits of other resources and lessons shortly.

In collaboration with NACE, our hope is to better prepare more able learners for the challenges they face. Our intervention aims to convey the message that students are important, are valued and matter. Ultimately, we aspire to establish positive learning environments in which perfectionistic students can thrive and flourish.

Post-script reflection: COVID-19

In this reflection, we consider the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on perfectionistic students.

The COVID-19 pandemic has swept across the globe and has disrupted students’ daily lives. With schools closed, students are facing unprecedented change and must learn to adapt to a new way of living. Amid increased isolation and overwhelming uncertainty, many students will be experiencing heightened stress and anxiety, and in its aftermath, it is likely that teachers and educators will observe a steep surge in mental health problems. In particular, the global health crisis will likely be exacerbating the stress, distress and mental health problems of perfectionistic students. As we undergo a period of great uncertainty, students will likely intensify their perfectionistic behaviours as a means to cope and gain some control. Undoubtedly, perfectionists will become further distressed when their expectations are not met.

Evidently students are experiencing severe disruption to their daily routines and goals, and thus, it is important they reappraise failures and setbacks as opportunities for growth and learn to adopt self-acceptance when goals do not go to plan. Teachers and educators can certainly help implement a sense of self-acceptance and significance and should remain a vital source of contact to calm the uncertainties and doubts of their students. Indeed, the benefits of showing students that they are significant and matter are particularly instrumental amidst the unfolding pandemic.

References:

- Flett, G. L. (2018). The psychology of mattering: Understanding the human need to be significant. London: Elsevier.

- Flett, G. L. (2018). Resilience to interpersonal stress: Why mattering matters when building the foundation of mentally healthy schools. In A. W. Leschied, D. H. Saklofske, & G. L. Flett (Eds.), Handbook of School-Based Mental Health Promotion. New York, NY: Springer Publishing.

- Flett, G. L., & Zangeneh, M. Mattering as a vital support for people during the COVID-19 pandemic: The benefits of feeling and knowing that someone cares during times of crisis. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 2, 106-123.

- Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Mikail, S. F. (2017). Perfectionism: A relational approach to conceptualization, assessment, and treatment. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2020). The perfectionism pandemic meets COVID-19: Understanding the stress, distress, and problems in living for perfectionists during the global health crisis. Journal of Concurrent Disorders, 2, 80-105.

Tags:

perfectionism

research

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Laura March,

11 May 2020

|

NACE Associate and R&D Hub Lead Laura March explains how Southend High School for Boys (SHSB) is ensuring learners continue to encounter “desirable difficulty” during the current period of remote learning.

In a recent ResearchEd presentation, Paul Kirshner delivered an insightful presentation based on the book Lessons for Learning. In one of his tips, he highlighted the need to avoid offering too much new subject matter during remote learning and to instead use this time to focus on maintaining the skills and knowledge that have been previously learnt. We know how easy it is to forget this learning without regular retrieval practice – we see this happen every year over the six-week summer break. Sometimes we underestimate the power of revision and repetition and this is a good opportunity to encourage pupils to consolidate knowledge from prior learning (see example retrieval grid).

For effective independent learning to take place, it is helpful to provide step-by-step worked solutions and provide alternative routes for all learners so they are offered support during their practice. On the other hand, we want there to be some form of “desirable difficulty” – not too hard, not too easy. Desirable difficulties are important because they trigger encoding and retrieval processes that support learning, comprehension and remembering. If, however, they are too difficult (the learner does not have the background knowledge or skills to respond to them successfully) they become undesirable difficulties and pupils can become disengaged, especially when working from home without teacher instruction and regular prompting (Bjork, 2009).

As time goes on, students’ internal resources start to increase as they begin to learn the content. At this point students are in danger of finding the task too easy. If there is no difficulty involved, then learning is less likely to occur. The best choice here is to start reducing the amount of support so pupils can achieve independence.

To help us reflect on this research, departments at SHSB have used two frameworks when considering and reviewing the tasks and activities being presented for remote learning:

Fisher and Frey: the gradual release of responsibility

In Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility (2008), Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey probe the how and why of the gradual release of responsibility instructional framework – a model which is deeply embedded across SHSB (see this summary of how we are using this model to inform our approach to remote learning). To what extent have we been providing tasks that fit into each of the four stages of effective structured learning? Is there a gradual shift in responsibility from the teacher to the pupil, moving from “I do” to “you do together” and “you do alone”? Sandringham Research School: the memory clock

We also wanted to think of simple ways to continue to achieve the interactivity that is crucial to teaching and learning. The “ memory clock” shared with us by Sandringham Research School has helped pupils revise and consolidate their knowledge. To avoid offering too much subject matter at once, the clock prompts pupils to structure learning into chunks and to always end with ‘assessing’ to self-regulate their own learning (see this example from SHSB Business department). It is important to ensure each study session has targeted questioning to check content is understood before moving on. Ensuring learning is transferred into long-term memory

A wealth of research tells us that delivering new information in small chunks is more effective for working memory – the type of memory we use to recall information while actively engaged in an activity. The capacity to store this information is vital to many learning activities in the classroom and just as important for remote learning. Presenting too much material at once may confuse students because they will be unable to process it using working memory. We can observe when this happens in the classroom and respond by explaining and repeating the material. It is more difficult for us to identify this in remote learning.

In both models outlined above, you will see recall and retrieval plays an important role. This has been embedded in our SIP over the last few years and departments at SHSB have been creative in revisiting material after a period of time using low stakes quizzes, retrieval grids, multiple choice questions and images. This review helps to provide some of the processing needed to move new learning into long-term memory and helps us to identify any misconceptions before introducing new material.

Additional reading and resources

- Daisy Christodoulou, “Remote learning: why hasn’t it worked before and what can we do to change that?” (March 2020) – includes a list of learning apps that are effective in helping pupils to recall and self-regulate their learning at home.

- Fisher, D. and N. Frey, Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A Framework for the Gradual Release of Responsibility, Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development, Alexandria, Virginia, 2008.

- Kornell, N., Hays, M. J., & Bjork, R. A. (2009). Unsuccessful retrieval attempts enhance subsequent learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 35, 989–998.

- Free resources: supporting challenge beyond the classroom – roundup of free resources from NACE partners and other organisations.

- NACE community forums – share what’s working for your staff and students.

Tags:

apps

free resources

independent learning

lockdown

memory

remote learning

research

retrieval

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By University of Oxford (Oxplore),

06 February 2020

|

The University of Oxford’s Oxplore website offers free resources to get students thinking about and debating a diverse range of “Big Questions”. Read on for three ways to get started with the platform, shared by Oxplore’s Sarah Wilkin…

Oxplore is a free, educational website from the University of Oxford. As the “Home of Big Questions”, it aims to engage 11- to 18-year-olds with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom. Big Questions tackle complex ideas across a wide range of subjects and draw on the latest research from Oxford.

Oxplore’s Big Questions reflect the kind of interdisciplinary and critical thinking students undertake at universities like Oxford. Each question is made up of a wide range of resources including: videos, articles, infographics, multiple-choice quizzes, podcasts, glossaries, and suggestions from Oxford faculty members and undergraduates.

Questioning can take many different forms in the classroom and is a skill valued in most subjects. Developing students’ questioning skills can empower them to:

- Critically engage with a topic by breaking it down into its component parts;

- Organise their thinking to achieve certain outcomes;

- Check that they are on track;

- Pursue knowledge that fascinates them.

Here are three ways Oxplore’s materials can be used to foster questioning and related skills…

1. Investigate what makes a question BIG

A useful starting point can be to get students thinking about what makes a question BIG. This can be done by displaying the Oxplore homepage and encouraging students to create their own definitions of a Big Question:

- Ask what unites these questions in the way we might approach them and the kinds of responses they would attract.

- Ask why questions such as “What do you prefer to spread on your toast: jam or marmite?” are not included.

- Share different types of questions like the range shown below and ask students to categorise them in different ways (e.g. calculable, personal opinion, experimental, low importance, etc.). This could be a quick-fire discussion or a more developed card-sort activity depending on what works best with your students.

2. Answer a Big Question

You could then set students the challenge of answering a Big Question in groups, adopting a research-inspired approach (see image below) whereby they consider:

- The different viewpoints people could have;

- How different subjects would offer different ideas;

- The sources and experts they could ask for help;

- The sub-questions that would follow;

- Their group’s opinion.

If you have access to computers, students could use the resources on the Oxplore website to inform their understanding of their assigned Big Question. Alternatively, download and print out a set of our prompt cards, offering facts, statistics, images and definitions taken from the Oxplore site:

Additional resources:

This activity usually encourages a lot of lively debate so you might want to give students the opportunity to report their ideas to the class. One reporter per group, speaking for one minute, can help focus the discussion.

3. Create your own Big Questions

We’ve found that no matter the age group, students love the opportunity to try thinking up their own Big Questions. The chance to be creative and reflect on what truly fascinates them has the appeal factor! Again, you might want to give students the chance to explore the Oxplore site first, to gain some inspiration. Additionally, you could provide word clouds and suggested question formats for those who might need the extra support:

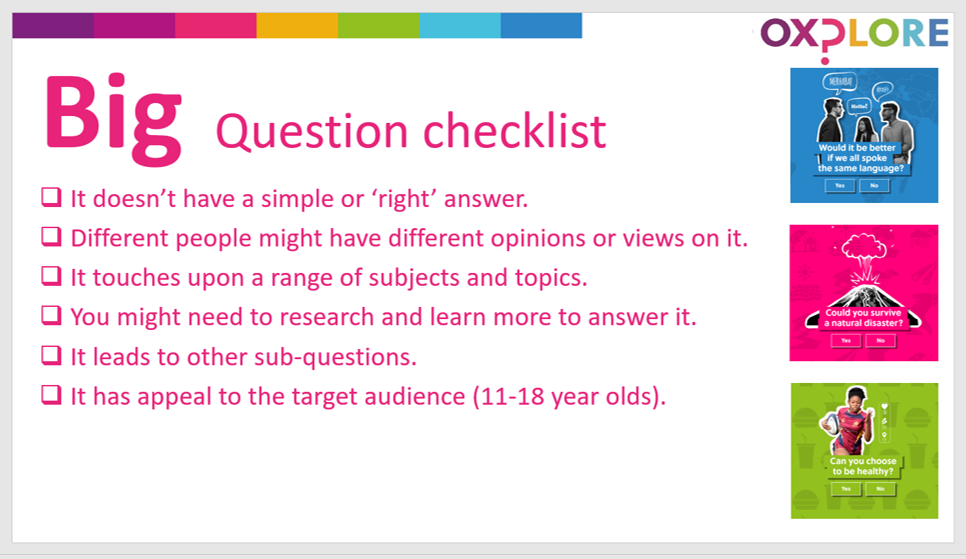

To encourage students to think carefully and evaluate the scope of their Big Question, you could present them with a checklist like the one below:

Extension activities could include:

- Students pitching their Big Question to small groups or the class (Why does it interest them? What subjects could it include? etc);

- This could feed into a class competition for the most thought-provoking Big Question;

- Students could conduct a mini research project into their Big Question, which they then compile as a homework report or present to the class at a later stage.

Take it further: join a Big Question debate

Each term the Oxplore team leads an Oxplore LIVE event. Teachers can tune in with their classes to watch a panel of Oxford academics debating one of the Big Questions. During the event, students have opportunities to send in their own questions for the panel to discuss, plus there are competitions, interactive activities and polls. Engaging with Oxplore LIVE gives students the chance to observe the kinds of thinking, knowledge and questions that academics draw upon when approaching complex topics, and they get to feel part of something beyond the classroom.

The next Oxplore LIVE event is on Thursday 13 February at 2.00-2:45pm and will focus on our latest Big Question: Is knowledge dangerous? If you and your students would like to take part, simply register here. You can also join the Oxplore mailing list to receive updates on new Big Questions and upcoming events.

Any questions? Contact the Oxplore team.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

enrichment

independent learning

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By York St John University,

30 January 2020

|

NACE is collaborating with York St John University on research and resources to help schools support more able learners with high levels of perfectionism. In this blog post, the university’s Luke F. Olsson, Michael C. Grugan and Andrew P. Hill outline the current research in this field and how growing awareness of the problem can be used to reshape classroom climates for the better.

The need to be or appear perfect pervades all aspects of society. In education, this is evident in that the experiences of many students appear to be underpinned by irrational beliefs that they need to perform perfectly. Perfectionism – an aspect of people’s personality that involves unrealistically high standards and overly critical evaluation – is therefore a particularly important characteristic to examine when considering the experiences of students.

Recent research suggests that perfectionism has become a hidden epidemic among students over the last 30 years, with students now more perfectionistic than ever before. In addition, this complex characteristic has been found to explain a wide range of outcomes among students. On one hand, some aspects of being perfectionistic are related to better academic performance. But, on the other hand, other aspects of perfectionism have been found to be significant sources of psychological distress for students, including burnout and depression.

Regarding more able learners, one interesting study of 10 samples including over 4,000 students found that intellectually gifted students tend to display higher levels of aspects of perfectionism than non-gifted students. One implication is that more able students are potentially at greater risk for mental health and wellbeing issues. This is evident in other research which has found that while more able students perform better academically, they can also be unhappier, lonelier, and have lower self-esteem. Tellingly, this may also be why more able students often respond to failure and setbacks more negatively.

As a consequence of what we have learned from research, it is apparent that more may need to be done to better support perfectionistic more able learners. Critically, if more able learners display signs of mental health difficulties, they need to be referred to a mental health professional. As such, those who work with more able students will need to be able to recognise when this might be the case. Improving mental health literacy among teachers is one way to do so.

There is also a great deal that can be done in regard to preventing mental health difficulties before they arise. We believe that prevention efforts aimed at reducing perfectionism are particularly important in this regard. One new area of research focuses on understanding how the environment created in achievement contexts such as the classroom can be designed in a way to discourage perfectionistic thinking among students. Our work in this area suggests that perfectionistic environments can involve a number of features including unrealistic standards (e.g. demanding extremely high standards regardless of ability), harsh criticism (e.g. fixating on minor mistakes and errors), manipulation and control (e.g. public punishments and rewards to motivate students), and anxiousness (e.g. signalling excessive concern over mistakes).

As awareness of the negative effects of perfectionism for more able learners students increases, there will be a greater emphasis on what teachers can do to support students. We believe that reshaping the classroom climate and making it less perfectionistic is one way teachers can help do so, and combat the hidden epidemic of perfectionism in young students.

NACE, York St John University and Haybridge High School (a NACE R&D Hub leading school) are currently trialling new resources to help schools raise awareness about perfectionism and support students with high levels of perfectionism. Watch out for updates in our monthly email newsfeed.

Tags:

collaboration

mindset

perfectionism

research

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Neil Jones,

22 January 2020

|

Neil Jones, Lead Practitioner for More Able Students at Impington Village College, shares key findings from the school’s focus on understanding the gender gap and moving beyond common stereotypes to develop more effective forms of support.

In common with many schools in England, our school identifies a gap in attainment between boys and girls at GCSE. In my role as Lead Practitioner for More Able Students, I had also noted an even larger gap, between boys and girls identified by teachers as having particularly high academic ability or talent in foundation subjects. It seemed there might have been a perception that girls (as a group) simply outperform boys (as a group). As a result, one of our strategic priorities for 2018-19 was that “all students make accelerated progress, with a particular focus on disadvantaged students and boys”.

We established a working group to investigate the causes of the attainment gap, whether anything was happening (or not happening) in classrooms to cause or sustain this gap, and what we could realistically do to address this. Our investigation aimed to build on previous work and existing practice, drawing on the insight and support of the middle leaders who make up our professional learning group, while fully engaging all teachers.

Phase 1: developing our thinking

The working group developed an online questionnaire to gather colleagues’ perceptions on the gender attainment and engagement gap. This included the 15 “barriers to boys’ learning” outlined in Gary Wilson’s influential book Breaking Through Barriers to Boys’ Achievement: Developing a Caring Masculinity (2013). It also contained a ‘pre-mortem’ question: “Imagine we innovated a whole range of things to improve boys' engagement and progress... and it was a spectacular failure. Write down examples of what we got wrong, and the impacts.” This open approach led to heated and productive debate, with a high response rate and a wide range of opinions and concerns expressed.

With suggestions from teachers across the school, we compiled a reading list around the gender gap (see below for examples), aiming to identify core themes and patterns. The key findings from our reading were that:

- In the UK, there has been a 9% gap in achievement between girls and boys since at least 2005; prior to that a gap was in evidence at O-Level and the 11+ exam.

- This gap is the same in many developed countries, but the narrative is different. In France, for example, the gap causes less consternation.

- Historically, almost all cultures have bemoaned adolescent boys’ “idleness” and their “ideal of effortless achievement”.

- The gap narrows in late adolescence and, internationally, by the age of 30 males have outstripped females in terms of their level of education and training, and earnings.

- Gender is an unstable indicator of individual student’s attainment and engagement: not all boys are underachieving, and not all girls are achieving.

- Gender-based approaches to teaching and learning are too often gimmicky, distracting and have no discernible effect on achievement. Learning has always been difficult; engagement comes from excellent subject knowledge of the teacher, supportive monitoring of understanding and confidence between teacher and learner.

Members of the working group visited several other schools, including one investigating boys who were following or bucking the trend of underachievement, and two using one-to-one mentoring to support underachieving students.

Phase 2: interventions

We asked the Director of Progress to share lists of students whose reports showed they were making both less progress and less effort than required. While this selection was gender-blind, the lists were, unsurprisingly, dominated by boys.

We then ran two six-week trials concurrently: a series of one-to-one 20-minute mentoring sessions with Year 8 students and a series of small-group, hour-long mentoring discussions with Year 10 students. The working group consulted during this process and fed back on what we judged was effective or otherwise, from our perspective and the students’.

Phase 3: lessons learned

We learned, crucially, that we mustn’t and can’t reduce our response to identity politics; what we can do is focus on teaching effectively and caring well.

Impact on teaching

The first impact on effective teaching is that our already tailored CPD will continue to focus on quality-first teaching. Members of the working group led well-received sessions scotching myths about the need for “boy-friendly” approaches such as competitions, kinaesthetic tasks, novelty/technology, befriending the “alpha” male, banter/humour, peer-to-peer teaching, negotiation, single-sex classes or male teachers.

What is proven to work instead, since time immemorial, is excellent teacher subject knowledge, firm but fair behaviour management and high-quality feedback – all of which are in place through our school’s existing assessment, accountability and quality management systems.

Impact on pastoral support

The second impact, on pastoral care, is that we understood that our underachieving students are, overwhelmingly but not exclusively, male; lack confidence; are therefore risk-averse academically; do not feel listened to; do not talk enough in order to explore their goals; cannot therefore link their learning meaningfully to their lives; feel lonely.

While Year 8 students responded quite well to one-to-one interventions, they were not yet mature enough to reflect very usefully on their experience. The two small groups of Year 10 students, however, were eager to talk, reflect and offer solidarity in encouraging ways. Insights from participants included:

- “We work hard for the teachers who like us.”

- “Extended day is pointless.”

- “If we’re put in intervention, no one explains why.’”

- “Interventions make me feel sh*t.”

- “You need confidence to be motivated.”

- “Some of our targets are genuinely too high.”

- “It feels like the school is just after the grades.”

- “If you share how you really feel with your mates it will all crumble.”

Phase 4: ongoing provision and evaluation

As of September 2019, we are running fortnightly after-school mentoring sessions for small groups of Year 11 students identified as being below target in progress and effort (chosen gender blind – 75% male, 25% female). These mentoring sessions run as an option for students, alongside two compulsory interventions for a much larger cohort of Year 11s. The first of these is an extended day, where students can revise together in the school library and focus on their own defined areas of study. The second is a series of extra lessons delivered at the end of the school day.

Keeping mentoring as an option for students (and their parents) seems to give them more sense of agency and responsibility. Numbers participating can fluctuate from week to week, but those participating are very positive. Many of the conversations involve making priorities and keeping things in perspective, and we encourage students to come up with their own solutions.

While it may be impossible to quantify the precise impact of this intervention with more able students, several students did better in their mocks than predicted, and more in line with their aspirational targets. Several parents, too, have been in touch to say that they find it makes a difference to their child’s attitude to learning. Goals post-16 are more defined. My overall hope for the programme is rather like Dr Johnson’s hope for literature: to help these young people find ways “better to enjoy life or, at least, endure it.” We will continue to monitor the programme’s popularity with students and its effectiveness.

Our approach frames underachievement as an issue requiring a further level of pastoral intervention, aimed at developing good habits of mind, a sense of purpose and the confidence these things bring. We hope these sessions will build solidarity between mentors and mentees, mentees and class teachers, and between the young people themselves. This will be vital if underachieving students are to reframe study and school life as opportunities to become excited about their aspirations and aims in life. Importantly, this intervention does not create gimmicky, evidence-free busywork for the teaching body, neither does it discriminate unfairly against girls.

Key takeaways:

- The attainment gap between boys and girls of this age is perennial. The work we do in schools can only go some of the way to address it, so concentrate on what is in your control: teaching well and caring well.

- Excellent teaching is what it always has been: that which allows students, male and female, to think. Learning is what it always has been: necessary, sometimes exciting, sometimes hard and distasteful. That goes for all of us, male and female.

- That said, all children need to develop positive habits of mind to stay motivated and happy enough that their actions have meaning. There will be challenges to this, different between time and time and community and community. To work out what these challenges are, and how to address them intelligently, use a wide range of data to ask meaningful questions.

- Loneliness and a lack of discussion about aims and habits are main drivers of underachievement and can quickly erode wellbeing. Boys as a group appear to feel these deficits more keenly than girls as a group (but not exclusively). We are in loco parentis and need to prioritise time and space for students who don’t do so at home to explore and examine how to develop successfully, in ways that are personal to them.

- Use your colleagues’ professional expertise and nous and encourage them to engage in contextual reading. It is alarming at the present time – perhaps encouraged by the instantaneity of the Twittersphere – how much change can be reactive and ignore lessons from the history of education policy. Before initiating any major or contentious change, aim to run it by as many colleagues as possible and get a pre-mortem. In our experience, colleagues’ insights, suggestions and misgivings all played a crucial role in preventing us making major mistakes.

Recommended reading:

- UNESCO 2019 Gender Review: https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/2019genderreport

- Gender and Education Association: www.genderandeducation.com

- Gender issues in schools: what works to improve achievement for boys and girls – DCSF 2009

- Gary Wilson, Breaking Through Barriers to Boys’ Achievement: Developing a Caring Masculinity (2013)

- Matt Pinkett and Mark Roberts, Boys Don’t Try? Rethinking Masculinity in Schools (2019) - review

Before you buy… For discounts of up to 30% from a range of education publishers, view the list of current NACE member offers (login required).

Share a review… Have you read a good book lately with relevance to provision for more able learners? Share it with the NACE community by submitting a review.

This blog post is based on a case study originally published in the SSAT journal Leading Change: The Leading Edge Network Magazine, Innovation Grants Special Edition 2018-2019, LC22 (Autumn 2019)

Tags:

gender

mentoring

myths and misconceptions

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Southend High School for Boys,

10 December 2019

|

Laura March, Hub Lead of the NACE R&D Hub at Southend High School for Boys, shares eight key issues discussed at the Hub’s inaugural meeting earlier this term.

Our inaugural NACE R&D Hub meeting was attended by colleagues from 12 schools, spanning a range of phases and subject areas. Ensuring the Hub meetings are focused on evidence and research allows us to respond to the masses of misinformation presented to us. A collaborative approach to understanding the needs of more able and talented (MAT) learners, and how to support them, enables colleagues to become more open and reflective in their discussions.

We started the meeting by sharing our own experience at Southend High School for Boys (SHSB), exploring our work towards gaining and maintaining the NACE Challenge Award over the last 15 years, and what strategies have had the biggest impact.

In the following discussion, it was interesting to explore what ‘differentiation’ means to different colleagues and key issues raised about what constitutes ‘good’ practice. It was also useful for colleagues from different fields – science, MFL, primary, physics, English and RE – to share approaches to developing writing skills, such as using ‘structure strips’, visualisers to model work, or tiered approaches to subject vocabulary. Finally, some questions were raised about communicating more able needs with parents; what should be included in the school’s more able policy; and how to monitor the impact of strategies on more able learners.

Here are eight key areas discussed during the meeting:

1. Strengthening monitoring and evaluation

This had been identified as an area for development at SHSB. MAT Coordinators and Subject Leaders are responsible for completing an audit to review their previous targets for more able learners and to outline opportunities, trips, competitions, resources and targets for the new academic year. This enables the MAT Lead to identify areas for pedagogical development so that targeted support can be put in place, as well as any budget requirements to purchase new resources.

2. Engaging with parents and carers

We shared the example of our parent support sheet. Not only are we bridging the gap between academic research and classroom practice, we aim to encourage a positive dialogue with parents by sharing the latest research on memory and strategies of how to stretch and challenge their sons and daughters at home. This has been very positive during parents’ evenings, with departments recommending extended reading; apps for effective revision such as Quizlet and Seneca; and You Tube videos for specific topics.

3. The zone of proximal development

As part of the Department for Education Teachers’ Standards, teachers must adapt teaching to respond to the strengths and needs of all pupils. This includes knowing when and how to differentiate appropriately and using approaches which enable pupils to be taught effectively (Department for Education, 2011). We looked at the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky) and how we ensure pupils avoid the ‘panic zone’.

As Martin Robinson (2013) says: “We are empowered by knowing things and this cannot be left to chance”. We cannot assume that more able learners know it all and simply leave them to their own devices in lessons. In contrast, we must avoid providing work that they are too comfortable with, resulting in easy learning and limited progress.

4. Myths and misconceptions

We looked at common myths surrounding more able learners and agreed that many of these are unfounded and untrue. Not all more able pupils are easy to identify because the opportunities are not always provided for talents to emerge. Likewise, SEN can mask multi-exceptionalities and we should ensure we have measures in place to identify these. We are also aware that the more able learners are not always the most popular or confident; many will suffer from ‘tall poppy syndrome’ or ‘imposter syndrome’.

5. High expectations for all

The key message is ensuring all learners have high aspirations and expectations and are provided with different routes to meet these. The research indicates that good differentiation is setting high-challenge learning objectives defined in detail with steps to success mapped out. It includes looking at the variety of ways teachers support and scaffold students to reach ambitious goals over time. We should avoid using language that sends a message to students that this part of the curriculum is not for them and that high expectations are only for ‘some’. We know that teaching to the top will raise aspirations for all learners.

“Effective differentiation is about ensuring every pupil, no matter their background and starting point, is headed towards the same destination, albeit their route and pace may differ. In other words, we should not ‘dumb down’ and expect less of some pupils, but should have high expectations of every pupil.” – Matt Bromley (SecEd, April 2019)

6. Developing literacy and writing skills

As part of our School Improvement Plan, we have a renewed focus on disciplinary literacy. Embedding this in lessons is a key way to ensure all pupils are able to express themselves within their subject domain.

“The limits of my language are the limits of my mind.” – Ludwig Wittgenstein

The range of writing we ask students to do is broad: analytical, evaluative, descriptive, explanatory, persuasive. Expecting them to shift between these without a clear structure is understandably going to create problems, so good modelling is essential. To support this, our MAT Coordinators have been using visualisers to model how to use key words in writing and to close the ‘knowing and doing gap’.

7. Metacognition

Externalising our thinking aloud enables pupils to improve metacognition. This is an essential skill in critical thinking and self-regulated, lifelong learning. It is important for learners to have skills in metacognition because they are used to monitor and regulate reasoning, comprehension, and problem-solving, which are fundamental components of effective learning.

8. Curriculum planning

We finished our meeting by looking at the new education inspection framework, specifically the guidance on subject curriculum content. Does it emphasise ‘enabling knowledge’ to ensure that it is remembered? Is the subject content sequenced so pupils build useful and increasingly complex schemata?

Our next Hub meeting will focus on the most effective ways to build up pupils’ store of knowledge in long-term memory.

References:

Before you buy… For discounts of up to 30% from a range of education publishers, view the list of current NACE member offers (login required).

Join your nearest NACE R&D Hub

NACE’s Research and Development (R&D) Hubs offer regional opportunities for NACE members to exchange effective practice, develop in-school research skills and collaborate on enquiry-based projects. Each Hub is led by a Challenge Award-accredited school, bringing together members from all phases, sectors and contexts. Participation is free for staff at NACE member schools. Find out more.

Tags:

collaboration

curriculum

differentiation

literacy

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

parents and carers

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Richard Bailey,

03 December 2019

|

In this article, originally published on the Psychology Today website, NACE patron Richard Bailey explores the problem(s) with praise…

There have been a number of reports and research articles trying to help teachers distinguish between effective and ineffective practices. One useful example comes from the University of Durham, when a team led by Professor Robert Coe reviewed a wide range of literature to find out what works, and what probably does not, in the Sutton Trust report What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research (2014).

Among the report’s examples of teaching techniques whose efficacy is not supported by research evidence was the widely discredited idea of "learning styles," as well as commonly used practices like "ability grouping" and "discovery learning." Even more surprising for many readers, perhaps, was the inclusion of "Use praise lavishly" in the list of questionable strategies. This is likely to be surprising because praise for students is seen as inherently affirming and beneficial by many people and is a core element of a positive philosophy of teaching, coaching, and parenting. In a similar way, criticism is now frequently condemned for being negative and harmful.

There are school programs and sports organisations based explicitly on the dual premises of plenty of praise and minimal criticism. And the rationale for this is usually that praise bolsters self-esteem and criticism harms it. In effect, this is the "gas gauge" theory of self-esteem, in which praise fills up the tank with good feelings and social approval, and criticism drains it.

Creating positive learning experiences

How can one not applaud the movement towards more positive approaches to education and sports? Especially for young people, these settings should be joyous, exciting experiences, and we know from vast amounts of research evidence from the United States and elsewhere that this is not always the case (link) (link).

We know, for example, that bullying, harassment and abuse still hide in dark corners, and that far too many parents, coaches, and teachers confuse infant needs with adult wants and infant games with professional competitions. We also know that such behaviours drive children away from engagement in and enjoyment of these pursuits because young people, if not all adults, know that learning, playing sports, and taking part in other activities are supposed to be fun.

Consider sports specifically for a moment. Research from the United States suggests that sports participation drops by 30% each year after age 10. According to a report from the National Alliance for Youth Sports, over 70% of children drop out of organised sports by age 13.

Numerous studies report that many children are put off participating in sports by an over-emphasis on winning and that this effect is especially strong among girls. Children are too often presented with a narrow and uninspiring range of opportunities, and while many love team games and athletic events, others find these traditional forms of physical activity irrelevant, boring, or upsetting.

Remember: this pattern of children dropping out from sports is happening as the health and happiness of young people are being compromised by unprecedented levels of physical inactivity. With activity levels low, and predicted to go even lower, we cannot afford to turn children off sports, and the movement toward more positive athletic experiences is undoubtedly a movement in the right direction.

There is a danger, though, in embracing praise as wholeheartedly and unconditionally as some parents, coaches, and teachers seem to have done.

When praise goes wrong…

Praise for students may be seen as affirming and positive, but a number of studies suggest that the wrong kinds of praise can be very harmful to learning. Psychologist Carol Dweck has carried out some of the most valuable research in this regard. In one study from 1998, fifth-graders were asked to solve a set of moderately difficult mathematical problems and were given praise that focused either on their ability ("You did really well; you're so clever") or on their hard work ("You did really well; you must have tried really hard”). The children were then asked to complete a set of more difficult challenges and were led to believe they had been unsuccessful. The researchers found that the children who had been given effort-based praise were more likely to show willingness to work out new approaches. They also showed more resilience and tended to attribute failure to lack of effort, not lack of ability. The children who had been praised for their intelligence tended to choose tasks that confirmed what they already knew, displayed less resilience when problems got harder, and worried more about failure.

What many might consider a common-sense approach – praising the child for being smart, clever, or "a natural" – turned out to be an ineffective strategy. The initial thrill of a compliment soon gave way to a drop in self-esteem, motivation, and overall performance. And this was the result of just one sentence of praise.

Some researchers have argued that praise that is intended to be encouraging and affirming of low-attaining students actually conveys a message of low expectations. In fact, children whose failure was responded to with sympathy were more likely to attribute their failure to lack of ability than those who were presented with anger. They claim:

“Praise for successful performance on an easy task can be interpreted by a student as evidence that the teacher has a low perception of his or her ability. As a consequence, it can actually lower rather than enhance self-confidence. Criticism following poor performance can, under some circumstances, be interpreted as an indication of the teacher's high perception of the student's ability.”

So, at the least, the perception that praise is good for children and criticism is bad needs a serious rethink: praise can hinder rather than help development and learning if given inappropriately. Criticism offered cautiously and wisely can be empowering.

Well-chosen criticism over poorly judged praise

These findings would seem to call for a reconsideration of a very widely held belief among teachers and coaches that they should avoid making negative or critical comments, and that if they must do so, then they should counter-balance a single criticism with three, four, or even five pieces of praise. This assumption is clearly based on the "gas gauge" model of self-esteem described earlier, viewing any negative comment as necessarily damaging, and requiring positive comments to be heaped around it in order to offset the harm.

I am unaware of any convincing evidence that criticism or negative feedback necessarily causes any harm to children's self-esteem. Of course, abusive comments and personal insults may well do so, but these are obviously inappropriate and unacceptable behaviours. Well-chosen criticism, delivered in an environment of high expectations and unconditional support, can inspire learning and development, whilst poorly judged praise can do more harm than good. Even relatively young children can tell the difference between constructive and destructive criticism, and it is a serious and unhelpful error to conflate the two.

We actually know quite a lot about effective feedback, and that knowledge is summarised nicely by the educational researcher John Hattie: "To be effective, feedback needs to be clear, purposeful, meaningful, and compatible with students’ prior knowledge, and to provide logical connections.”

I suggest that it would be extremely difficult to deliver feedback that is clear, purposeful, etc. in the context of voluminous praise. Eventually, the parent, teacher, or coach simply ends up making vague, meaningless or tenuous platitudes. And this can cause more damage to the learner-teacher relationship than criticism.

Build confidence by being present

The psychoanalyst Stephen Grosz describes a conversation he had with a school teacher named Charlotte Stiglitz – the mother of the Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz:

"I don't praise a small child for doing what they ought to be able to do," she said. "I praise them when they do something really difficult – like sharing a toy or showing patience. I also think it is important to say ‘thank you’, … but I wouldn't praise a child who is playing or reading.”

Grosz watched as a four-year-old Stiglitz showed her a picture he had been drawing. She did not do what many would have done (including me when I taught this age group) and immediately praise such a lovely drawing. Instead, she had an unhurried conversation with the child about his picture. “She observed, she listened. She was present,” Grosz noted.

I think Stephen Grosz’s conclusion from this seemingly everyday event is correct and important: being present for children builds their confidence by demonstrating that they are listened to. Being present avoids an inherent risk associated with excessive praise, as with any type of reward, that the praise becomes an end in itself and the activity is merely a means to that end. When that happens, learning, achievement, and the love of learning are compromised.

Praise is like sugar. Used too liberally or in an inappropriate way, it spoils. But used carefully and sparingly, it can be a wonderful thing!

This article previously appeared in Psychology Today (https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/smart-moves).

Copyright Richard Bailey

Tags:

confidence

feedback

mindset

motivation

myths and misconceptions

research

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|