Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

independent learning

oracy

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

critical thinking

language

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By NACE,

05 December 2024

Updated: 05 December 2024

|

“Our world is at a unique juncture in history, characterised by increasingly uncertain and complex trajectories shifting at an unprecedented speed. These sociological, ecological and technological trends are changing education systems, which need to adapt. Yet education has the most transformational potential to shape just and sustainable futures.” (UNESCO, Futures of Education)

NACE welcomed the opportunity to respond to the Curriculum and Assessment Review (which closed for submissions on 22 November), based on our work with thousands of schools across all phases and sectors over the last 40 years.

Our response first emphasised the importance of an overarching, strategic vision for curriculum reform based on:

- Evidence and beliefs about the purposes of education and schooling at this point in the century;

- Knowledge of human capacities and capabilities and how they are best nurtured and realised;

- Addressing the needs of the present generation while building the skills of future generations;

- An approach that is sustainable and driven and coordinated by national policy;

- Appropriate selection of knowledge/content and teaching methodologies that are fit for purpose and flexibility in curriculum planning and implementation;

- Recognition of system and structural changes in and outside schools to support curriculum reform;

- Acknowledgement of the professional expertise and agency of educators and the importance of school-level autonomy;

- The perspectives and experiences of groups experiencing barriers to learning and opportunity (equity and inclusion).

Core foundations

NACE supports the importance of a curriculum built on core foundations which include:

- “Language capital” (wide-ranging forms of literacy and oracy) – viz evidence supporting the importance of reading, comprehension and vocabulary acquisition in successful learning and their place at the heart of the curriculum

- Numeracy and mathematical fluency

- Critical thinking and problem solving

- Emotional and physical well-being

- Metacognitive and cognitive skills

- Physical and practical skills

- An introduction to disciplinary domains (with a focus not just on content but on initiation into key concepts and processes)

The design of the curriculum needs to allow for the space and time to develop these skills as key threads throughout.

Whilst the current National Curriculum stresses the importance of developing basic literacy and numeracy skills at Key Stage 1, to open the doors to all future learning, schools continue to be pressured by the expectations of the wider curriculum/foundation subjects. This needs to be revisited to ensure that literacy, numeracy and wider skills can be securely embedded before schools expose children to a broader curriculum.

Content: knowledge and competencies

In secondary education an increasingly concept-/process-based approach to delivery of disciplinary fields should be envisaged alongside ‘knowledge-rich’ curriculum models already pervasive in many schools. Core foundation competencies and skills should continue to be developed, ensuring that learners acquire so-called ‘transformative competencies’ such as planning, reflection and evaluation. The curriculum must enshrine the ‘learning capital’ (e.g. language, cultural, social and disciplinary capital) which will enable young people to adapt to, thrive in and ultimately shape whatever the future holds.

Knowledge, skills, attitudes and values are developed interdependently. The concept of competency implies more than just the acquisition of knowledge and skills; it involves the mobilisation of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values in a range of specific contexts to meet complex demands. In practice, it is difficult to separate knowledge and skills; they develop together. Researchers have recognised how knowledge and skills are interconnected. For example, the National Research Council's report on 21st century competencies (2012) notes that “developing content knowledge provides the foundation for acquiring skills, while the skills in turn are necessary to truly learn and use the content. In other words, the skills and content knowledge are not only intertwined but also reinforce each other.”

Consideration needs to be given to breadth versus balance versus depth in curriculum design, alongside the production of guidance which articulates key and ‘threshold’ concepts and processes in subject areas. NACE training and development stresses the importance of teachers and learners understanding the concept of ‘desirable difficulty’ as this is essential in developing resilience and, therefore, supporting wellbeing. It is difficult to provide learners with appropriate levels of challenge/difficulty and time to work through these if curriculum content is over-heavy. In the later stages of schooling a greater emphasis could be placed on interdisciplinary links and advanced critical thinking competencies.

At all stages of education evidence-based approaches to pedagogy and assessment to maximise student learning should be incorporated into curriculum design. Such practices should also incorporate adaptations and recognition of different learning needs and address issues of equity and removing barriers to learning.

Summary

In schools achieving high-quality provision of challenge for all, the design of the curriculum includes planned progression and continuity for all groups of learners through key stages. Where school leaders understand the steps needed to develop deep learning, knowledge and understanding, rich content and secure skills are developed.

The Curriculum Review presents a much-needed opportunity to interrogate the purposes of curriculum and 21st century schooling, the fitness of the current National Curriculum and potential reforms needed. The review must be holistic, vision- and evidence-led, as well as recognising that a ‘national curriculum’ is only one part of the overall learning experience of children. Revised curriculum proposals and their implementation may also rely on reviewing and transforming existing school structures and systems as well as national resourcing issues to ensure more equitable access to high-quality education no matter where young people live and attend school. The proposals must also take account of ongoing teacher supply and quality issues and possible reforms to teacher education and professional development to match the aspirations of an English education system which is equitable, inclusive and one of the best in the world.

Most importantly, the new curriculum proposals must go much further than previously in trying to ensure that all young people leave school equipped to realise their ambitions for their personal and working lives, and to contribute to shaping their own and others’ destinies in a more equitable and caring society, along with the courage to face the unknown challenges which lie ahead.

Tags:

assessment

curriculum

policy

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Gianluca Raso,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

Gianluca Raso, Senior Middle Leader for MFL at NACE Challenge Award-accredited Maiden Erlegh School, explores the real meaning of “adaptive teaching” and what this means in practice.

When I first came across the term “adaptive teaching”, I thought: “Is that not what we already do? Surely, the label might be new, but it is still differentiation.” Monitoring progress, supporting underperforming students and providing the right challenge for more able learners: these are staples in our everyday practice to allow students to actively engage with and enjoy our subjects.

I was wrong. Adaptive teaching is not merely differentiation by another name. In adaptive teaching, differentiation does not occur by providing different handouts or the now outdated “all, most, some” objectives, which intrinsically create a glass ceiling in students’ achievement. Instead, it happens because of the high-quality teaching we put in for all our students.

Adaptive teaching is a focus of the Early Career Framework (DfE, 2019), the Teachers’ Standards, and Ofsted inspections. It involves setting the same ambitious goals for all students but providing different levels of support. This should be targeted depending on the students’ starting points, and if and when students are struggling.

But of course it is not as simple as saying, “this is what adaptive teaching means: now use it”.

So how, in practice, do we move from differentiation to adaptive teaching?

A sensible way to look at it is to consider adaptive teaching as an evolution of differentiation. It is high-quality teaching based on:

- Maintaining high standards, so that all learners have the opportunity to meet expectations.

Supporting all students to work towards the same goal but breaking the learning down – forget about differentiated or graded learning objectives.

- Balancing the input of new content so that learners master important concepts.

Giving the right amount of time to our students – mastery over coverage.

- Knowing your learners and providing targeted support.

Making use of well-designed resources and planning to connect new content with pupils' prior knowledge or providing additional pre-teaching if learners lack critical knowledge.

- Using Assessment for Learning in the classroom – in essence check, reflect and respond.

Creating assessment fit for purpose – moving away from solely end of unit assessments.

- Making effective use of teaching assistants.

Delivering high quality one-to-one and small group support using structured interventions.

In conclusion, adaptive teaching happens before the lesson, during the lesson and after the lesson.

Aim for the top, using scaffolding for those who need it. Consider: what is your endgame and how do you get there? Does everyone understand? How do you know that? Can everyone explain their understanding? What mechanisms have you put in place to check student understanding ? Encourage classroom discussions (pose, pause, pounce, bounce), use a progress checklist, question the students (hinge questions, retrieval practice), adapt your resources (remove words, simplify the text, include errors, add retrieval elements).

Adaptive teaching is a valuable approach, but we must seek to embed it within existing best practice. Consider what strikes you as the most captivating aspect of your curriculum in which you can enthusiastically and wisely lead the way .

Ask yourself:

- Could all children access this?

- Will all children be challenged by this?

… then go from there…

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

differentiation

feedback

pedagogy

professional development

progression

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

20 February 2023

Updated: 20 February 2023

|

NACE Research and Development Director Dr Ann McCarthy explores the ethos behind this year’s NACE R&D Hub on the theme “rethinking assessment” – including some key questions for all school leaders and teachers to consider.

“Rethinking assessment” is the focus of one of our NACE Research and Development Hubs this year. The question we are asking ourselves is:

If I rethink an aspect of assessment, to include it as part of the learning process, will more able pupils have a better understanding of the learning process; as such will they exhibit greater depth, complexity or analytic skills in their learning?

Within this Hub, leaders and teachers are seeking to improve the value and effectiveness of assessment. Some are making small changes to classroom practice; others are seeking to make changes within teams; and others are making strategic decisions which include a change in school policies.

One might ask why this is of interest and indeed necessary when there are so many initiatives being introduced into our schools. The answer is that assessment dominates the learning environment in that it provides summative evaluations and provides instructional feedback to help learners progress. It also has the potential to enable pupils to become powerful, autonomous and self-regulating learners, both now and into the future.

However, assessment practice does not always benefit more able learners and often detracts from the learning itself. In this article I begin by raising awareness of potential hazards when planning assessment, before thinking about the purpose of assessment and the possibilities open to us if we rethink our own practice.

Tests, examinations and potential hazards

Every year following the publication of examination results we hear the statistics about the change in numbers achieving specific grades. Schools are then judged on the effectiveness of reaching performance thresholds. It is not surprising that curriculum in some schools is at risk of becoming narrow and entirely examination-focused.

For those that oppose the current system, there are arguments that methods for obtaining grades or performance measures should be reviewed and changed. There has been discussion about whether employers and universities understand the endpoint grades. At all stages of learning endpoint grades do not always lead to progression in learning. Prior learning is not always understood as learners move from primary to secondary, Year 11 to sixth form or on to schools, colleges, universities and employment.

Another issue is that testing does not necessarily respond to the different ways pupils learn, the additional needs they might have or the wider intellectual, developmental or metacognitive gains which might be possible. Pupils with differing learning needs or experiences can find it difficult to demonstrate their skills and abilities within the format of the current assessments.

More able pupils deserve the highest grades and the expectation from parents and pupils is that this will become a reality. This puts pressure on both the class teacher and school to provide a curriculum which consistently leads to these outcomes. It also places pressure on the pupils to achieve an examination or test standard bounded by a fixed curriculum. Schools carefully package the curriculum into small but connected areas of learning which can be delivered, revised and assessed effectively.

However, another potential hazard lies in the preparation of the curriculum in that pupils can experience too many assessments. Schools wishing to maintain a prescribed standard each year with a trajectory of performance with the target grade as the endpoint will often use data-driven assessment. Here they risk placing numeric data ahead of meaningful learning. Pupils are then at risk from pressure imposed by continuous high- and low-stakes assessment detached from learning. In the worst-case scenario, more time is invested in measuring learning rather than developing the pupils’ potential.

Another problem associated with a prescribed endpoint measure is that the assessments which pupils experience throughout the period of instruction mirror the endpoint assessment even though pupils may not have the maturity, linguistic capability or experience to make the greatest learning gains from the experience. This is often seen most clearly in the secondary phase of learning when pupils are given GCSE-style questions as young as age 11.

Regardless of all these points, the reality is that for all the problems which exist within the current system, we live in a country where our qualifications have international recognition and value. So how then, working within the current constraints, can we help our pupils to become confident and successful learners while avoiding some of these hazards?

What then are we seeking to rethink, if not the system itself?

In rethinking assessment, we seek to enable our pupils to achieve the highest standards; because they have mastered the learning through effective curriculum, teaching, learning and assessment. To achieve this, we need to imagine what pupils have the potential to know, learn, think and do. We also need to think beyond the limitations of compulsory prescribed content. We can enable more able pupils with their variety of backgrounds, learning needs and potential to acquire a deeper understanding of subject, context, applications, and of their own learning. We can provide pupils with more information about the nature of learning and their own learning so that they feel in control of the process.

Deciding the purpose of assessment

When rethinking assessment, it must align with the educational philosophy held by all stakeholders. Different schools will adopt different approaches to assessment, but the most effective practices exist when the purpose of assessment is clearly articulated and understood. It works well when there is consistent practice, which not only informs the teaching but also facilitates learning and engages pupils in their learning. Assessment should not create an additional workload, nor should it be focused on the acquisition of data which is detached from learning.

There have been many attempts to characterise good assessment practice. An example here comes from The Assessment Reform Group who summarised the characteristics of assessment that promotes learning using the following seven principles:

- It is embedded in a view of teaching and learning of which it is an essential part;

- It involves sharing learning goals with pupils;

- It aims to help pupils to know and to recognise the standards they are aiming for;

- It involves pupils in self-assessment;

- It provides feedback which leads to pupils recognising their next steps and how to take them;

- It is underpinned by confidence that every student can improve;

- It involves both teacher and pupils reviewing and reflecting on assessment data.

Broadfoot et al., 1999, p. 7

When planning formative assessment teachers may want to reflect on the view expressed by Black and Wiliam that it is:

“the extent that evidence about student achievement is elicited, interpreted, and used by teachers, learners, or their peers, to make decisions about the next steps in instruction that are likely to be better, or better founded, than the decisions they would have taken in the absence of the evidence that was elicited.”

Black & Wiliam, 2009, p. 9

When deciding the purpose of assessment, we need to be clear about the way in which it will feed information back into the learning process. Students need to understand themselves as learners and know what else they need to learn. This moves us away from activities which are pressured and demotivating. It moves us towards assessment choices which increase motivation and focus. Good assessment practice will allow pupils to take greater control of their learning when they understand the level of challenge, can set themselves challenges and utilise information or feedback to make progress.

When you rethink assessment:

- How would you summarise the characteristics of good assessment in your school?

- What is the purpose of the planned assessments?

- What impact will they have on learning and progress?

- What impact will assessment have on teaching?

- How will pupils use the assessment and feedback to regulate their own learning

To what extent will authentic assessment enhance learning?

Authentic assessment practices are seen to be favourable by linking the classroom to wider experience. However, there are a wide range of views on what this might look like. We often see examination questions which are set within a “real life context”. The difficulty with this approach is that the questions become complicated and often distract the pupils from the learning rather than contributing to it. Gulikers, Bastiaens and Kirschner proposed assessment which relates more directly to the context in which the learning might be experienced. Their model enabled:

“students to use the same competencies, or combinations of knowledge, skills, and attitudes that they need to apply in the criterion situation in professional life.”

Gulikers et al, 2004, p. 69

Litchfield and Dempsey (2015), proposed authentic assessment would lead to in-depth learning and the application of knowledge. Assessment activity becomes meaningful, interesting and collaborative. Through authentic practice pupils can develop a greater range of learning attributes. They become more active learners using critical thinking, problem solving and metacognitive strategies.

Whether or not we use the idea of authentic assessment as a driver for our assessment practices, we would all agree that we want pupils to engage in meaningful and interesting activities. If our assessment practices sit within the learning process and enable pupils to work collaboratively to achieve more, then the assessment activity and the learning activity can combine to improve the quality of learning and cognitive development.

Evaluating our practice

Once a decision has been made to rethink assessment, we need to revisit our aims and principles.

Do your aims and principles:

- Promote assessment as integral to learning and the shaping of future learning?

- Promote high expectations for all pupils and ensure assessment places no inadvertent ceiling on achievement?

- Value and represent achievement for all pupils across the breadth and depth of the curriculum using a variety of approaches?

- Recognise that assessment needs to be constructive, motivate pupils, extend learning, and develop resilient, independent learners?

- Take account of how the expanding knowledge of the science of how pupils learn is changing modes of assessing what pupils know?

These principles are used by NACE members to audit assessment practice in their schools. Here we can see how the pupil is catered for within the process. We seek to help the pupil to become more resilient, resourceful and independent. We want both the pupil and the teacher to have realistic high expectations so that there is no ceiling on learning but also no undue pressure by praising the outcome over the effort.

The assessment itself is integral to the learning process. The assessment shapes the learning and the learner. It guides the teacher’s practice and is dependent on a good understanding of both the curriculum and cognition. By rethinking assessment we can still achieve the endpoint measures but also go beyond this to create an environment for learning which nourishes and develops each individual.

Metacognition and assessment

If we are truly committed to using assessment as a practice integral to learning and as a learning tool for both teacher and pupil, we need a good knowledge of the curriculum, the connections between areas of learning, potential for depth and breadth of learning beyond the limitations of core curriculum, cognition and cognitive processes. When assessment practices enable pupils to develop metacognition and metacognitive skills, they will be able to respond well to new experiences and learning.

Dunlosky and Metcalfe (2009) describe three processes of metacognition: knowledge, monitoring, and control.

- Knowledge: understanding how learning works and how to improve it.

- Monitoring: self-assessment of understanding,

- Control: any required self-regulation.

I would argue that rethinking assessment should be driven by our increased understanding of metacognition. Self-assessment skills sit at the heart of metacognitive competencies. If we view metacognition as “thinking about thinking” or “learning about learning” we can then see that the pupils need answers to some questions.

- What should I be thinking about?

- What do I need to know?

- Am I understanding this material at the level of competency needed for my upcoming challenge?

- What am I trying to learn?

- How am I learning?

- Do I need to change my focus?

- Do I need to change my learning strategy?

Self-assessment is a core metacognitive skill that links understanding of learning and how to improve it to the development of self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is a person’s belief in an ability to succeed in a particular situation. Self-efficacy is the product of experience, observation, persuasion, and emotion. If pupils learn to monitor their developing competencies and control their cognitive strategies, they will be able to organise and execute the actions needed to respond to new learning experiences.

Next steps for teachers and leaders

All schools, regardless of outcomes, will review and evaluate practice each year. As a part of this it is important to revisit assessment practices within the classroom, across subjects and phases and at a whole-school strategic level.

Within the classroom the teacher can begin by imagining small changes which can lead to a better learning experience and a greater impact on learning and metacognition. These changes might include:

- Changes to recall practices with acquired vocabulary or knowledge being used in different contexts;

- Organisation of collaborative learning groups where understanding can be observed through pupils’ interaction;

- Pre-planned “big questions” and extended questioning which challenges understanding;

- Independent research, challenges or project work;

- Changes to feedback and response activities;

- Use of entry and exit tickets;

- Use of “cutaway” learning models;

- Pupil-led diagnostic responses;

- Pupil self-selected challenge and extension activities;

- Whole-class marking, feedback and active response.

Many of these are possibly in use at present but they have greatest impact when planned within the lesson structure and used consistently so that teachers and pupils share an understanding of learning and learning potential. When planning within a subject or phase, a strategy which is shared between teachers and understood by pupils will reap the greatest rewards. If pupils know what they are doing and why they are doing it, they will recognise the importance of the activity. When activities combine cumulatively to improve knowledge, learning and understanding of both subject and self, then pupils will make the greatest gains.

The preparation for endpoint examination then appears in the final months of study, when the format of the testing is explained, shared and practised; not to increase knowledge and understanding, but to secure outcomes. Pupils will be able to approach this preparation, as they would any testing or competitive situation, as training and warm-up for the final event. Their education as a whole having been confident and secure, they will approach this new challenge with a sense of purpose and self-belief.

So how then can leaders manage a whole-school strategy? This can often prove an obstacle when planning to make change. Leaders must know how well pupils are progressing, how well the curriculum is being delivered and the quality of teaching in the classroom. This is where school ethos, aims and principles are important. By agreeing a model for assessment practice which does not overload teachers but provides evidence of the quality of education, leaders can themselves adopt the same assessment and evaluation models as they use in their classrooms.

When teachers all work towards a common and agreed framework for curriculum, teaching, learning and assessment, pupils do not need to be tested to measure teacher performance. High-quality professional development, dialogue and collaboration supports high-quality practice. Good-quality systems provide the narrative which expose the quality of learning and performance within the school. It is the responsibility of school leaders to create a narrative which can be evidenced through consistency of belief and practice in all classrooms. The conversation then returns to learning and teaching and individual pupils’ needs or aspirations rather than numeric data tracking.

Whatever style of data tracking and targets a school chooses to use, it is important to keep the pupils and their learning at the centre of the conversation.

Taking steps to rethink assessment

The NACE “Rethinking Assessment” R&D Hub is supporting teachers and leaders to take a small step in making a change in practice. The Hub supports those wishing to plan a small-scale project through which they can evidence the impact of change. Here we can see how activities which may be evident in other schools can be trialled over a short period of time so that their true impact can be observed. Teachers and leaders participating in the Hub are engaged in a variety of activities as they seek to rethink assessment practices in their classrooms and schools. These include:

- Improving pupils’ understanding of assessment by providing greater guidance;

- Enabling pupils to respond well to questions which have greater stretch and challenge;

- Make better use of feedback and individual response activities;

- Reconfiguring the sequence of assessment so that there is a more coherent structure;

- Developing assessment strategies for project-based learning which enable pupils to challenge themselves and extend their knowledge;

- Making use of “what if…” questions and developing teachers’ skills in new ways of assessing the responses;

- Refining the language of feedback so that pupils can extend and deepen thinking;

- Updating marking and feedback policies and strategies so that there is a whole-staff appreciation of effective practice;

- Improving the use of disciplinary language within teaching, learning and assessment;

- Planning assessments within a metacognitive model.

The ideas proposed for rethinking assessment in all these schools build on existing good practice. Teachers have examined the context within their schools and evaluated the impact of current practice. From this they hypothesised on elements of practice which could be improved, replaced or refined. They are now seeking to enhance existing good practice to meet the aims and principles as discussed. Regardless of your position in the school it is possible to revisit your assessment practices.

Share your experience with others

- Do you routinely use an assessment practice or approach which helps you to assess, monitor or evaluate learning well?

- Do you have a good assessment strategy which you can share which enables pupils to learn well or helps them to improve their performance?

- Do you have some advice for others which you can share?

- Can you describe some changes to classroom assessment practices which have improved learning?

- Can you share a whole-school assessment strategy which has made a difference in your school?

If you feel you can add to the conversation, please contact us so we can help to share your successes with the wider NACE community.

References

- Black, P. J., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5-31.

- Broadfoot, P. M., Daugherty, R., Gardner, J., Gipps, C. V., Harlen, W., James, M., & Stobart, G. (1999). Assessment for learning: beyond the black box. Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge School of Education.

- Dunlosky, J. & Metcalfe, J. (2009). Metacognition. Sage Publications Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA.

- Gulikers, J. T., Bastiaens, T. J., & Kirschner, P. A. (2004). A five-dimensional framework for authentic assessment. Educational technology research and development, 52(3), 67-86.

- Litchfield, B. C., & Dempsey, J. V. (2015). Authentic assessment of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2015(142), 65-80.

Tags:

assessment

feedback

leadership

metacognition

pedagogy

professional development

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Claire Gadsby,

16 January 2023

|

Claire Gadsby, educational trainer, author and founder of Radical Revision, shares five practical approaches to make your students’ revision more effective.

Did you know that 88% of pupils who revise effectively exceed their target grade? Interestingly, most pupils do not know this and fail to realise exactly how much of a gamechanger revision really is. Sitting behind this simple-looking statement, though, lies the key question: what is effective revision?

In my revision work with thousands of pupils around the world, I have not met many who are initially overjoyed at the thought of revision, often perceiving it as an onerous chore to be endured on their own before facing the trial of the exams. It does not have to be this way and I am passionate about taking the pain out of the process.

Revision can – and should – be fun. Yes, you read that right. The following strategies may be helpful for you in motivating and supporting your pupils on their revision journey.

1. Timer challenge

Reassure your pupils that not everything needs revising: lots is actually still alive and well in their working memory. Put a timer on the clock and challenge pupils to see how much they can recall about a particular topic off the top of their head in just five minutes. The good news is that this is ‘banked’: now what pupils need to do is to focus their revision on the areas they did not write down. It is only at this point that they need to start scanning through notes to identify things they had missed.

2. Bursts and breaks

It is quite common for young people to feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount of revision. Be confident when you reassure them that ‘little and often’ really is the best way to tackle it. Indeed, research suggests that a short burst of 25 minutes revision followed by a five-minute break is the ideal. Make the most of any ‘dead time’ slots in the school day to include these short revision bursts.

3. Better together

Show pupils the power of collaborative revision. Working with at least one other person is energising and gets the job done quicker. Activities such as ‘match the pairs’ or categorising tasks have the added advantage of also promoting higher-order thinking and discussion.

4. Take the scaffolds away

It is not effective to simply keep reading the same words during revision. Instead, ‘generation’ is one of the key strategies proven to support long-term learning. Tell pupils not to write out whole words in their revision notes. Instead, they should write just the first letter of key words and then leave a blank space. When they look back at their notes, their brain will be challenged to work harder to recall the rest of the missing word which, in turn, makes it more likely to be retained for longer.

5. Playful but powerful

We know that low-stakes quizzing is ideal, and my ‘lucky dip’ approach is helpful here. Keep revision information, such as key terms and concepts, ‘in play’ by placing them in a gift bag or similar. Mix these up and pull one out at random to check for understanding. Quick, out of context, checks like this are a type of inter-leaving which is proven to strengthen recall.

Following feedback from pupils and their parents that they would benefit from more sustained support and structure in the lead up to their exams, in 2021 I launched Radical Revision – an online revision programme for schools with short video tutorials (ideal for use in tutor time) to introduce students to our cutting-edge revision techniques. The online portal also contains a plethora of downloadable resources and CPD for teachers, as well as resources and webinars for parents. For more information please visit the Radical Revision website, where you can sign up to access a free trial version. We’re also offering NACE members a 15% discount on the cost of an annual subscription for your school – log in to the NACE member offers page for details.

Sources: National strategies GCSE Booster materials, DfES publications 2003.

For even more great practical ideas from Claire, join us the NACE annual conference on 20 June 2023 – details coming soon!

Tags:

assessment

collaboration

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

retrieval

revision

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Rob Bick,

09 December 2022

|

Rob Bick, Curriculum Leader of Mathematics and Assistant Headteacher, explains how the use of exit tickets has improved assessment (and teacher workload) at Haybridge High School and Sixth Form.

The maths department at Haybridge High School introduced exit tickets almost 10 years ago, inspired by a suggestion in Doug Lemov’s book ‘Teach like a Champion 2.0’. Here’s how it works in our department…

In general, students would be given a coloured piece of A5/A6 paper towards the end of a lesson. On the whiteboard their teacher would write a hinge question (or questions) to assess whether or not students have a reasonable understanding of the key concept(s) covered in that lesson. A shared bank of exit ticket questions is available, often using exam-style questions, but teachers are encouraged to use a flexible approach and set their own question(s) in response to how the lesson has progressed. We wouldn’t use a pre-suggested exit ticket for a lesson if that was no longer appropriate.

Students copy the exit ticket question(s) down on to their piece of paper and then write their answers, showing full workings. As students leave the lesson they hand their completed exit ticket to their teacher. The teacher will then mark the exit tickets with either a tick or cross, no corrections, putting them into three piles: incorrect, correct, perfect. Those with perfect (and correct if applicable) exit tickets are awarded achievement points. Marking the exit tickets is very quick and easy and gives the teacher a quick insight into the success of the lesson, whether a concept needs to be retaught, whether the class is ready to build on the key concepts, any common misconceptions that need to be addressed, whether students are using correct mathematical language…

After the starter activity of the next lesson, the teacher will review the exit tickets using the visualisers in a variety of ways. This could be to model a perfect solution which students can then use to annotate their own returned exit ticket, or to explore a common misconception. The teacher may display an exit ticket and say “What’s wrong with this?”. Names can be redacted but hopefully the teacher has established a “no fear of mistakes” environment where students are comfortable with their exit ticket being displayed. Students always correct their own errors using coloured pens for corrections to make them stand out. Annotated exit tickets are then stuck into books.

Exit tickets can also be set to aid recall of previous topics. This is particularly helpful when the scheme of work will soon be extending upon some form of previous knowledge. For example, exit tickets could be used to prompt students to recall how to solve linear equations in advance of a lesson on simultaneous linear equations, or to review basic trigonometry before moving on to 3D trigonometry.

Other than marking formal assessments, this is the only other marking expected of staff and the expectation is that an exit ticket will take place every other lesson. In sixth form we turn this on its head and do entrance tickets, so questions are asked at the start of the lesson using exact questions which were set for homework due that lesson. This gives teachers a quick method of assessing students’ understanding and identifying those who haven’t completed their homework successfully. It saves a great deal of teacher time and yet provides a much clearer understanding of how our students are progressing.

Obviously, exit and entrance tickets are just one approach to check for understanding. We also use learning laps with live formative assessment during every lesson. We make extensive use of mini-whiteboards and hinge questioning to quickly assess understanding. We also only use cold calling when asking for a response from the class – all students are asked to answer a problem and then one is asked to share their response – rather than choosing only from those with hands up.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective assessment practices – including new initiatives and well-established practices. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- Which area of assessment is used most effectively?

- What assessment practices are having the greatest impact on learning?

- How do teachers and pupils use the assessment information?

- How do you develop an understanding of pupils’ overall development?

- How do you use assessment information to provide wider experience and developmental opportunities?

- Is assessment developing metacognition and self-regulation?

Read more about our focus on assessment.

Tags:

assessment

feedback

maths

pedagogy

progression

retrieval

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

25 April 2022

Updated: 21 April 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research & Development Director, shares examples from our recent member meetup on the theme “rethinking assessment”.

As part of NACE’s current research into effective assessment strategies, we recently brought our member schools together for a meetup at New College Oxford, to share thoughts and examples of successful practice. We examined assessment as a systematic procedure drawing from a range of activities and evidence. We saw how this contrasted with the necessary but limiting practice of testing, which is a product not open to interpretation.

Practitioners attending the meetup generously shared established and emerging approaches to assessment and were able to discuss the related strengths and challenges. They had time to examine the ways in which new practices had been introduced and strategies used to overcome any barriers or difficulties. Most importantly, they articulated the positive impact that these practices were having on the learning and development of pupils in their care.

When schools develop successful assessment strategies, they consider the following questions:

- How does it link to whole school vision?

- Where does it sit inside the model for curriculum, teaching and learning?

- Who is the assessment for?

- What is the plan for assessment?

- What types of assessment can be used?

- What is going to be assessed?

- What evidence will result from the assessment?

- How will the evidence be used or interpreted?

- How can assessment information be used by teacher and pupil?

- What impact does assessment information have on teaching and learning?

- How does assessment impact on cognition, cognitive strategies, metacognition and personal development?

Example 1: “purple pen” at Toot Hill School

Toot Hill School shared how the use of the “purple pen” strategy can be effective in developing the learning and metacognition of secondary-age pupils.

Pupils most commonly receive feedback at three stages in the learning process:

- Immediate feedback (live) – at the point of teaching

- Summary feedback – at the end of a phase of knowledge application/topic/assessment

- Review feedback – away from the point of teaching (including personalised written comments)

A purple pen can be used to:

- Annotate purposeful learning steps;

- Make notes when listening to key learning points;

- Respond to whole-class feedback;

- Facilitate peer assessment;

- Respond to teacher marking;

- Question and develop themes to achieve learning objectives;

- Recognise key vocabulary;

- Explain learning processes.

Much of the success of this strategy at Toot Hill School can be attributed to the clear teaching and learning strategy which is in place and the consistency of practice across the school. Some schools have used this practice in the past and abandoned it due to inconsistency, lack of evidence of impact or increased workload. At Toot Hill this is not the case as its introduction included a consideration of overall practice and workload. Pupils are fully conversant with the aims and expectations. Subject leaders are well-informed and work together to ensure that pupils moving between subjects have the same expectation. Here we find assessment planned carefully within ambitious teaching and learning routines.

This example of effective assessment demonstrates the importance of feedback within the assessment process. In this example pupils are being assessed but also assessing their own learning. They have greater control of their learning. This practice is particularly effective for more able learners, who will make their own notes on actions needed to improve. They are also influential in promoting good learning behaviours within their classrooms as they model actions needed for improved learning. This practice keeps the focus of assessment on the needs of the learner and the information needed by the learner to become more independent and self-regulating.

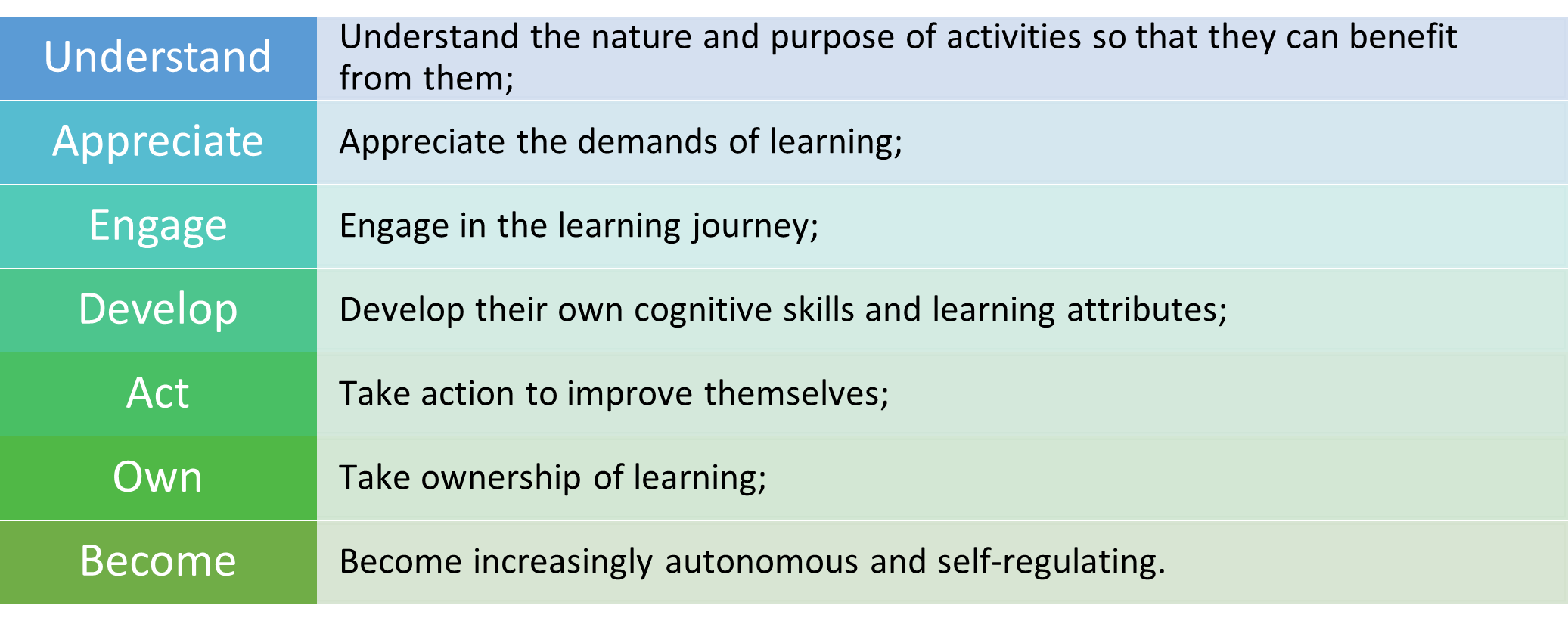

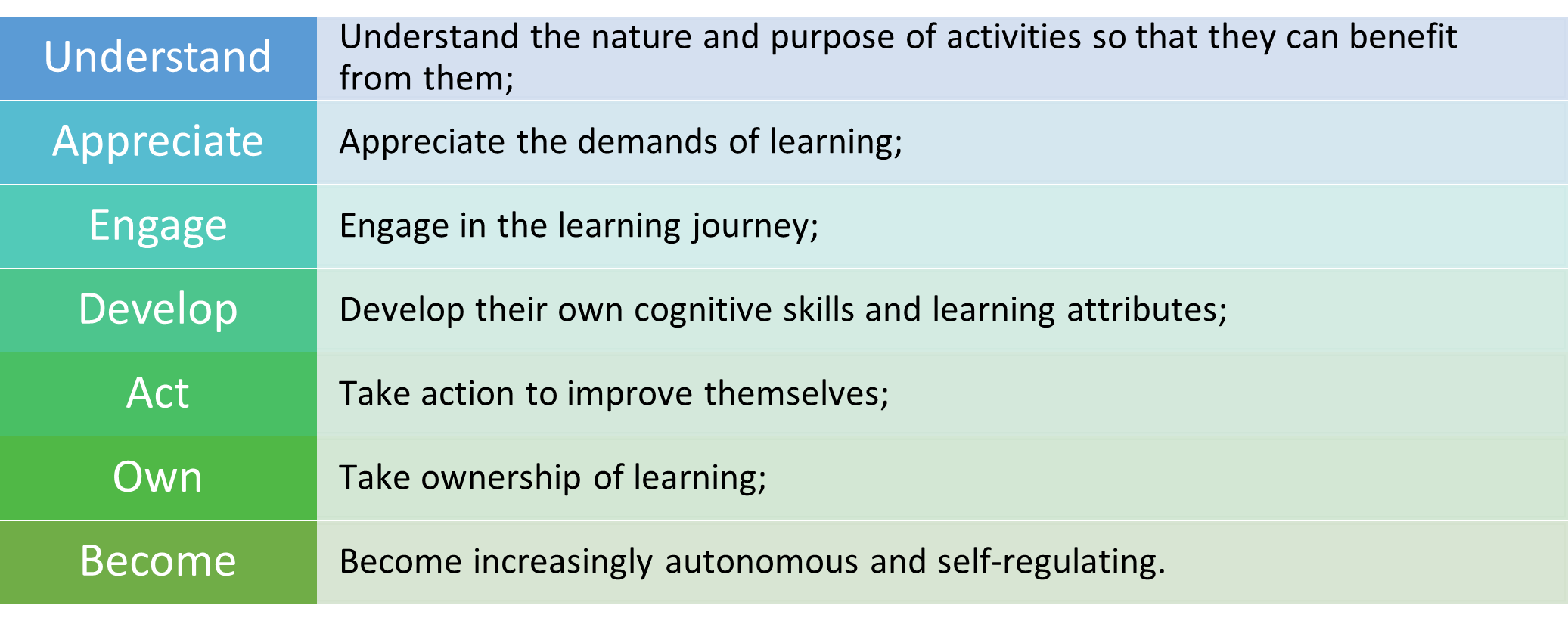

Successful assessment practice places the pupil at the heart of the process. Assessment enables pupils to:

Example 2: “closing the loop” at Eggar’s School

Eggar’s School shared details of an initiative which is being piloted, aiming to improve outcomes in formal assessments. A template for whole-class “feed-forward” sheets has been introduced. This shared template enables teachers to keep a track record of assessments. It also tracks their intentions to adapt their teaching as a result of evaluating student assessments. They are focusing on “closing the loop” in feedback and learning.

The rationale behind the strategy is that it is easier for teachers to:

- Reflect on attainment over the course of the year, comparing pieces of work by the same student over time;

- Compare attainment between year groups and ask: Has teaching improved? Are there different needs / interventions required in the current cohort compared with those of previous years?

- Get a snapshot of a student’s work.

The approach also allows the Lead Teacher and Curriculum Leader to spot-check progress and discuss successes or concerns with the class teacher.

As this is an emerging practice, the teachers are learning and adapting their practice to make it increasingly useful. The school’s findings include:

- The uniformity of the layout of the feed-forward sheets is helping students to understand the feed-forward process.

- Completion of the feed-forward sheets was originally time-consuming, but is now taking less time.

- In feed-forward lessons live modelling is being used rather than pre-prepared models.

- More prepared models are created in advance of assessment points as guidelines/reference tools for students.

- Prepared models are used after formal assessment as a comparison for students to use when self- or peer-assessing their performance.

- The specific focus in the feed-forward sheets on SPaG has been a helpful reminder to utilise micro-moments in lessons to consolidate technical skills.

- The teacher uses a ‘Students of Concern’ section (not visible to students) to provide additional support and interventions and to reflect on the success of any previous intervention.

- ‘Closing the Loop’ books have been introduced and have become a powerful tool in improving the value of assessment as a teaching and learning experience. These use a template for whole-class feedback and enable teachers to keep a track record of assessments and a track of their intentions in terms of adaptations to teaching as a result of assessment information about students’ knowledge, understanding and progress.

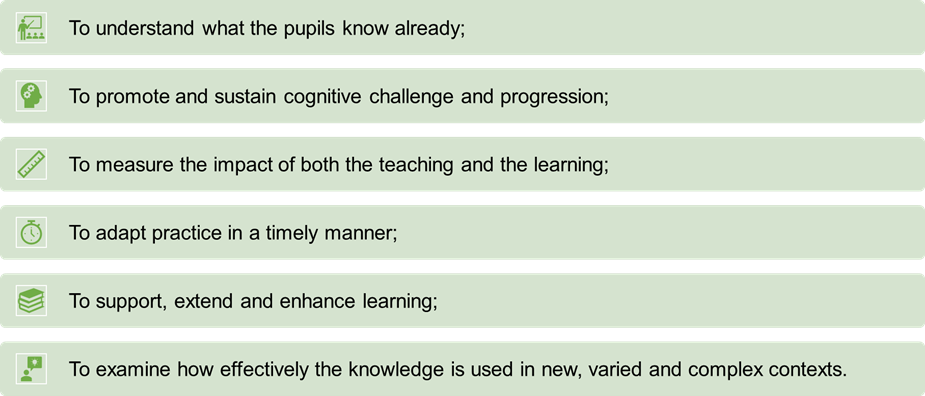

This is an example of assessment which is increasing the teacher’s criticality of the teaching and learning process and their expertise within this. The pupils benefit from the focused response to their work and the modelled practice. This exemplifies aspects of assessment used to achieve high-quality teaching:

“Rethinking assessment” across the NACE community

Other NACE member schools shared their experiences, including:

- A focus on understanding personal development – considering ways in which pupils’ overall experience and development can be better understood and supported, as part of assessment.

- Retrieval introduced as a core and explicit part of lesson sequences and schemes of work.

- The use of science practical activities linked to examination questions, to expose pupils to desirable difficulties. These reveal pupils’ knowledge and skills; support development and progress; and provide information needed to scaffold support at an individual level.

- Changes to reporting introduced to empower pupils, as well as informing leaders, teachers and parents.

- Developing the use of Rosenshine’s principles with a focus on higher-order questioning; this challenges more able pupils to think more deeply, extends their thinking, and has demonstrable benefits for other pupils in a mixed ability classroom.

- Models of excellence shared with pupils.

- Use of film resources and extended book study to encourage critical thinking and application of skills.

These varied approaches to assessment reflect the different contexts in which teachers work. They include assessment being used in three distinct ways:

Each of these has a place within teaching and learning. It is important that each type of assessment has a clear purpose and will impact effectively on the quality of teaching and the depth of learning. Pupils need to develop both within and beyond the content constraints of a curriculum. They need to learn about concepts as well as content. They need to understand what they are learning and how it links to other areas of learning. They need to develop cognition and cognitive strategies so that their learning is more useful to them both within school and in life.

The greatest gains can be achieved when the assessment itself is a part of learning and pupils have greater ownership of the process. As assessment practices develop within schools, the aim should be to upskill pupils so that they have the information they need to become self-regulating and to develop metacognitively.

Key factors for successful implementation

During the meetup, we observed that the schools with well-established assessment practice have introduced this within a whole-school ethos and strategy. Staff and pupils have a shared understanding of the use, purpose and benefits of the practice. Middle leaders are influential in the development of strategy, its consistency and the successful use within a subject specific context. Pupils are at the heart of the model and interact with assessment and feedback to improve their own learning. They develop cognitively and understand their own thinking and learning.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective assessment practices – including new initiatives, and well-established practices.

You may feel that some of the examples cited above are similar to practices in your own school, or you may have well-developed assessment models that would be of interest to others. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- Which area of assessment is used most effectively?

- What assessment practices are having the greatest impact on learning?

- How do teachers and pupils use the assessment information?

- How do you develop an understanding of pupils’ overall development?

- How do you use assessment information to provide wider experience and developmental opportunities?

- Is assessment developing metacognition and self-regulation?

Read more:

Plus: NACE is partnering with The Brilliant Club on a webinar exploring the links between metacognition and assessment, featuring practical examples from NACE member schools. Details coming soon – check our webinars page.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

collaboration

feedback

metacognition

pedagogy

progression

research

Permalink

| Comments (1)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

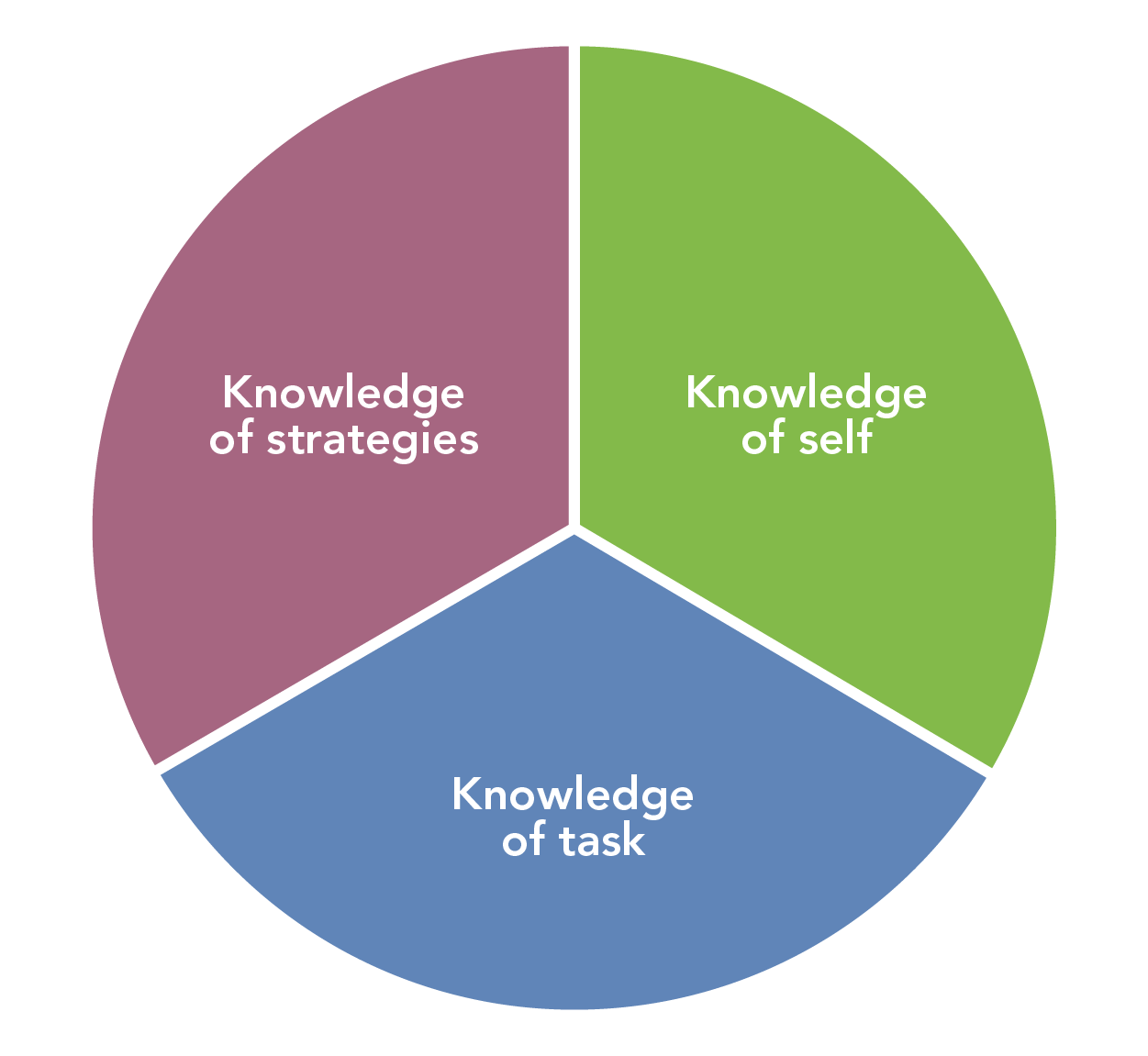

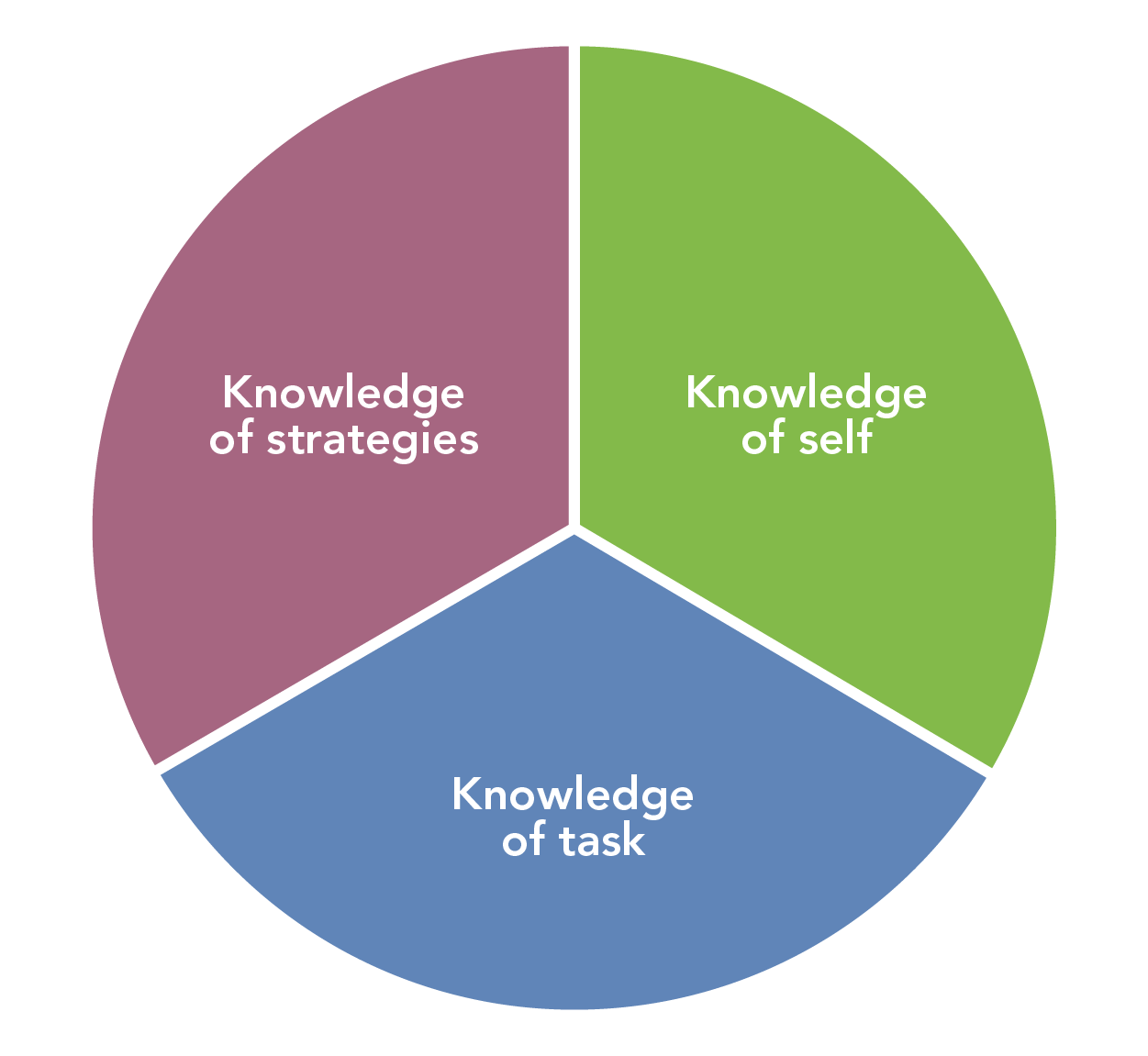

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 October 2021

|

NACE Research & Development Director Dr Ann McCarthy shares key principles for effective assessment planning and practice, within cognitively challenging learning environments.

Following two academic years of uncertainty and alternative arrangements for teaching and assessment, the conversation regarding testing and assessment has become increasingly important. Upon return to the routines of day-to-day classroom teaching, schools have had to find ways to assess knowledge, progress and understanding achieved through distance learning or redesigned classroom practices. For older pupils there has been a need to provide evidence to examination boards to secure grades and guarantee appropriate progression routes. This inherent need to provide checks and balances before pupils’ achievement is recognised can become a distraction from the art of teaching. In fact, Rimfield et al (2019) found a very high agreement between teacher assessments and exam grades in English, maths, and science.

- Could we examine less often and use classroom-based assessment more often?

- Should we rethink testing and assessment and their position in the learning process?

Testing vs assessment

The terms test and assessment are often used interchangeably, but in the context of education we need to recognise the difference. A test is a product which is not open to interpretation; it uses learning objectives and measures success achieved against these. Teachers use tests to measure what someone knows or has learned. These may be high-stakes or low-stakes events. High-stakes tests may lead to a qualification, grading or grouping, whereas low-stakes tests can support cognition and learning. Testing takes time away from the process of learning and as such testing should be used sparingly, when necessary and when it contributes significantly to the next steps in teaching or learning.

Assessment, by contrast, is a systematic procedure which draws on a range of activities or evidence sources which can then be interpreted. Regardless of the position teachers hold regarding the use of testing and examinations, meaningful assessment remains an essential part of teaching and learning. Assessment sits within curriculum and pedagogy, beginning with diagnostic assessment to plan learning which best reflects the needs of the learner. A range of formative assessment activities enable the teacher and pupils to understand progress, improve learning and adapt the learning to reflect current needs. Endpoint activities can be used as summative assessments to appreciate the degree to which knowledge has been acquired, alongside varied and complex ways in which that knowledge can be used.

Assessment might be viewed in three different ways: assessment of learning; assessment for learning; and assessment as learning. The choice of assessment practice will then impact on its use and purpose. Regardless of the process chosen and the procedures used, the teacher must remember that the value of the assessment is in the impact it has on pedagogy and practice and the resulting success for the pupils, rather than as an evidence base for the organisation.

NACE research has shown that cognitively challenging experiences – approaches to curriculum and pedagogy that optimise the engagement, learning and achievement of very able young people – will have a significant and positive impact on learning and development. But how can we see this working, and what role does assessment play? When planning for cognitively challenging learning, assessment planning should reflect the priorities for all other aspects of learning.

A strategic approach to assessment which supports cognitively challenging learning environments

When considering the place of assessment in education, teachers must be clear about:

- What they are trying to assess;

- How they plan to assess;

- Who the assessment is for;

- What evidence will become available;

- How the evidence can be interpreted;

- How the information can then be used by the teacher and the pupil;

- The impact the information has on the planned teaching and learning;

- The contribution assessment makes to cognition, learning and development.

Effective assessment is integral to the provision of cognitively challenging learning experiences. With careful and intentional planning, we can assess cognitive challenge and its impact, not only for the more able pupils, but for all pupils. Assessments are used to measure the starting point, the learning progression, and the impact of provision. When working with more able pupils, in cognitively challenging learning environments, the aim is to extend assessment practices to include assessment of higher-order, complex and abstract thinking.

When used well, assessment provides the teacher with a detailed understanding of the pupils’ starting points, what they know, what they need to know and what they have the potential to do with their learning. The teacher can then plan an engaging and exciting learning journey which provides more able pupils with the cognitive challenge they need, without creating cognitive overload.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has joined with others to recognise the importance of cognitive science to inform interventions and classroom practice. Spaced learning, interleaving, retrieval practice, strategies to manage cognitive load and dual coding all support cognitive development – but are dependent on effective assessment practices which guide the teaching and learning. The best assessment methods are those that integrate fully within curriculum teaching and learning.

Assessment and classroom management