Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Gianluca Raso,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

Gianluca Raso, Senior Middle Leader for MFL at NACE Challenge Award-accredited Maiden Erlegh School, explores the real meaning of “adaptive teaching” and what this means in practice.

When I first came across the term “adaptive teaching”, I thought: “Is that not what we already do? Surely, the label might be new, but it is still differentiation.” Monitoring progress, supporting underperforming students and providing the right challenge for more able learners: these are staples in our everyday practice to allow students to actively engage with and enjoy our subjects.

I was wrong. Adaptive teaching is not merely differentiation by another name. In adaptive teaching, differentiation does not occur by providing different handouts or the now outdated “all, most, some” objectives, which intrinsically create a glass ceiling in students’ achievement. Instead, it happens because of the high-quality teaching we put in for all our students.

Adaptive teaching is a focus of the Early Career Framework (DfE, 2019), the Teachers’ Standards, and Ofsted inspections. It involves setting the same ambitious goals for all students but providing different levels of support. This should be targeted depending on the students’ starting points, and if and when students are struggling.

But of course it is not as simple as saying, “this is what adaptive teaching means: now use it”.

So how, in practice, do we move from differentiation to adaptive teaching?

A sensible way to look at it is to consider adaptive teaching as an evolution of differentiation. It is high-quality teaching based on:

- Maintaining high standards, so that all learners have the opportunity to meet expectations.

Supporting all students to work towards the same goal but breaking the learning down – forget about differentiated or graded learning objectives.

- Balancing the input of new content so that learners master important concepts.

Giving the right amount of time to our students – mastery over coverage.

- Knowing your learners and providing targeted support.

Making use of well-designed resources and planning to connect new content with pupils' prior knowledge or providing additional pre-teaching if learners lack critical knowledge.

- Using Assessment for Learning in the classroom – in essence check, reflect and respond.

Creating assessment fit for purpose – moving away from solely end of unit assessments.

- Making effective use of teaching assistants.

Delivering high quality one-to-one and small group support using structured interventions.

In conclusion, adaptive teaching happens before the lesson, during the lesson and after the lesson.

Aim for the top, using scaffolding for those who need it. Consider: what is your endgame and how do you get there? Does everyone understand? How do you know that? Can everyone explain their understanding? What mechanisms have you put in place to check student understanding ? Encourage classroom discussions (pose, pause, pounce, bounce), use a progress checklist, question the students (hinge questions, retrieval practice), adapt your resources (remove words, simplify the text, include errors, add retrieval elements).

Adaptive teaching is a valuable approach, but we must seek to embed it within existing best practice. Consider what strikes you as the most captivating aspect of your curriculum in which you can enthusiastically and wisely lead the way .

Ask yourself:

- Could all children access this?

- Will all children be challenged by this?

… then go from there…

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

differentiation

feedback

pedagogy

professional development

progression

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Rob Bick,

09 December 2022

|

Rob Bick, Curriculum Leader of Mathematics and Assistant Headteacher, explains how the use of exit tickets has improved assessment (and teacher workload) at Haybridge High School and Sixth Form.

The maths department at Haybridge High School introduced exit tickets almost 10 years ago, inspired by a suggestion in Doug Lemov’s book ‘Teach like a Champion 2.0’. Here’s how it works in our department…

In general, students would be given a coloured piece of A5/A6 paper towards the end of a lesson. On the whiteboard their teacher would write a hinge question (or questions) to assess whether or not students have a reasonable understanding of the key concept(s) covered in that lesson. A shared bank of exit ticket questions is available, often using exam-style questions, but teachers are encouraged to use a flexible approach and set their own question(s) in response to how the lesson has progressed. We wouldn’t use a pre-suggested exit ticket for a lesson if that was no longer appropriate.

Students copy the exit ticket question(s) down on to their piece of paper and then write their answers, showing full workings. As students leave the lesson they hand their completed exit ticket to their teacher. The teacher will then mark the exit tickets with either a tick or cross, no corrections, putting them into three piles: incorrect, correct, perfect. Those with perfect (and correct if applicable) exit tickets are awarded achievement points. Marking the exit tickets is very quick and easy and gives the teacher a quick insight into the success of the lesson, whether a concept needs to be retaught, whether the class is ready to build on the key concepts, any common misconceptions that need to be addressed, whether students are using correct mathematical language…

After the starter activity of the next lesson, the teacher will review the exit tickets using the visualisers in a variety of ways. This could be to model a perfect solution which students can then use to annotate their own returned exit ticket, or to explore a common misconception. The teacher may display an exit ticket and say “What’s wrong with this?”. Names can be redacted but hopefully the teacher has established a “no fear of mistakes” environment where students are comfortable with their exit ticket being displayed. Students always correct their own errors using coloured pens for corrections to make them stand out. Annotated exit tickets are then stuck into books.

Exit tickets can also be set to aid recall of previous topics. This is particularly helpful when the scheme of work will soon be extending upon some form of previous knowledge. For example, exit tickets could be used to prompt students to recall how to solve linear equations in advance of a lesson on simultaneous linear equations, or to review basic trigonometry before moving on to 3D trigonometry.

Other than marking formal assessments, this is the only other marking expected of staff and the expectation is that an exit ticket will take place every other lesson. In sixth form we turn this on its head and do entrance tickets, so questions are asked at the start of the lesson using exact questions which were set for homework due that lesson. This gives teachers a quick method of assessing students’ understanding and identifying those who haven’t completed their homework successfully. It saves a great deal of teacher time and yet provides a much clearer understanding of how our students are progressing.

Obviously, exit and entrance tickets are just one approach to check for understanding. We also use learning laps with live formative assessment during every lesson. We make extensive use of mini-whiteboards and hinge questioning to quickly assess understanding. We also only use cold calling when asking for a response from the class – all students are asked to answer a problem and then one is asked to share their response – rather than choosing only from those with hands up.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective assessment practices – including new initiatives and well-established practices. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- Which area of assessment is used most effectively?

- What assessment practices are having the greatest impact on learning?

- How do teachers and pupils use the assessment information?

- How do you develop an understanding of pupils’ overall development?

- How do you use assessment information to provide wider experience and developmental opportunities?

- Is assessment developing metacognition and self-regulation?

Read more about our focus on assessment.

Tags:

assessment

feedback

maths

pedagogy

progression

retrieval

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

25 April 2022

Updated: 21 April 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research & Development Director, shares examples from our recent member meetup on the theme “rethinking assessment”.

As part of NACE’s current research into effective assessment strategies, we recently brought our member schools together for a meetup at New College Oxford, to share thoughts and examples of successful practice. We examined assessment as a systematic procedure drawing from a range of activities and evidence. We saw how this contrasted with the necessary but limiting practice of testing, which is a product not open to interpretation.

Practitioners attending the meetup generously shared established and emerging approaches to assessment and were able to discuss the related strengths and challenges. They had time to examine the ways in which new practices had been introduced and strategies used to overcome any barriers or difficulties. Most importantly, they articulated the positive impact that these practices were having on the learning and development of pupils in their care.

When schools develop successful assessment strategies, they consider the following questions:

- How does it link to whole school vision?

- Where does it sit inside the model for curriculum, teaching and learning?

- Who is the assessment for?

- What is the plan for assessment?

- What types of assessment can be used?

- What is going to be assessed?

- What evidence will result from the assessment?

- How will the evidence be used or interpreted?

- How can assessment information be used by teacher and pupil?

- What impact does assessment information have on teaching and learning?

- How does assessment impact on cognition, cognitive strategies, metacognition and personal development?

Example 1: “purple pen” at Toot Hill School

Toot Hill School shared how the use of the “purple pen” strategy can be effective in developing the learning and metacognition of secondary-age pupils.

Pupils most commonly receive feedback at three stages in the learning process:

- Immediate feedback (live) – at the point of teaching

- Summary feedback – at the end of a phase of knowledge application/topic/assessment

- Review feedback – away from the point of teaching (including personalised written comments)

A purple pen can be used to:

- Annotate purposeful learning steps;

- Make notes when listening to key learning points;

- Respond to whole-class feedback;

- Facilitate peer assessment;

- Respond to teacher marking;

- Question and develop themes to achieve learning objectives;

- Recognise key vocabulary;

- Explain learning processes.

Much of the success of this strategy at Toot Hill School can be attributed to the clear teaching and learning strategy which is in place and the consistency of practice across the school. Some schools have used this practice in the past and abandoned it due to inconsistency, lack of evidence of impact or increased workload. At Toot Hill this is not the case as its introduction included a consideration of overall practice and workload. Pupils are fully conversant with the aims and expectations. Subject leaders are well-informed and work together to ensure that pupils moving between subjects have the same expectation. Here we find assessment planned carefully within ambitious teaching and learning routines.

This example of effective assessment demonstrates the importance of feedback within the assessment process. In this example pupils are being assessed but also assessing their own learning. They have greater control of their learning. This practice is particularly effective for more able learners, who will make their own notes on actions needed to improve. They are also influential in promoting good learning behaviours within their classrooms as they model actions needed for improved learning. This practice keeps the focus of assessment on the needs of the learner and the information needed by the learner to become more independent and self-regulating.

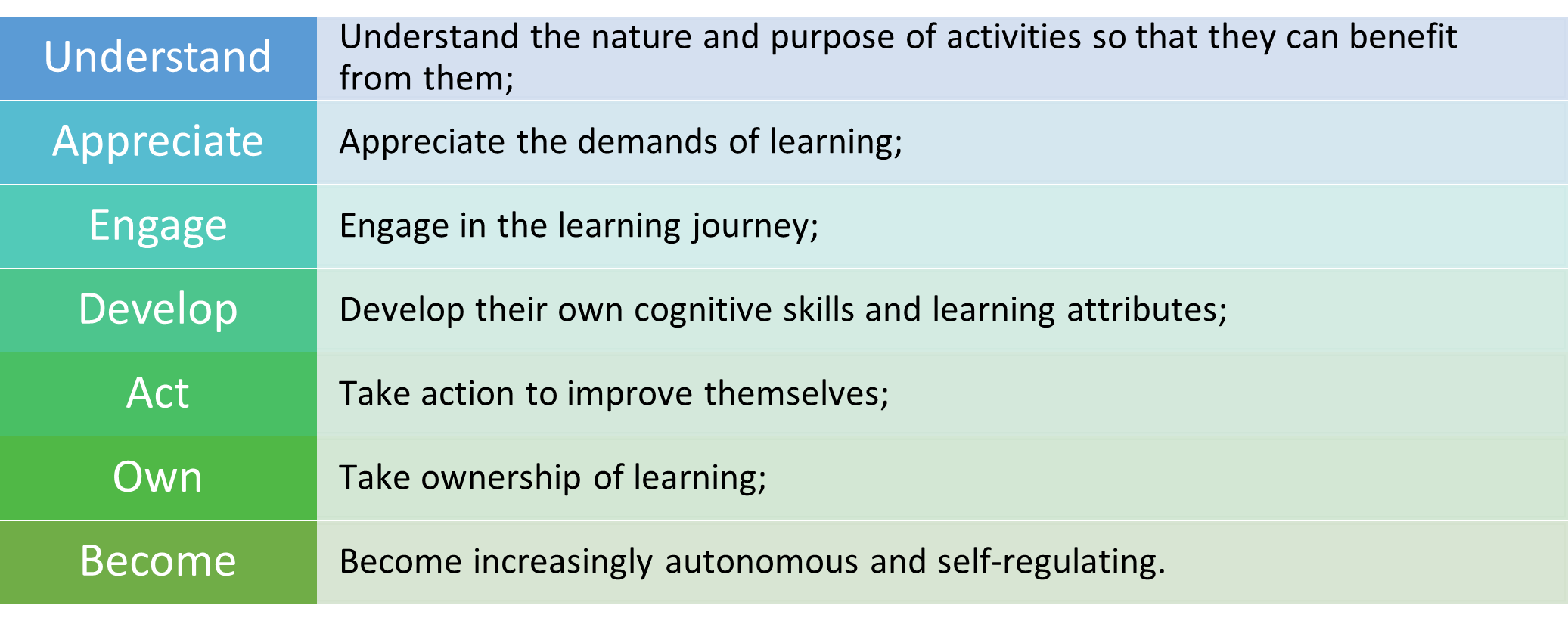

Successful assessment practice places the pupil at the heart of the process. Assessment enables pupils to:

Example 2: “closing the loop” at Eggar’s School

Eggar’s School shared details of an initiative which is being piloted, aiming to improve outcomes in formal assessments. A template for whole-class “feed-forward” sheets has been introduced. This shared template enables teachers to keep a track record of assessments. It also tracks their intentions to adapt their teaching as a result of evaluating student assessments. They are focusing on “closing the loop” in feedback and learning.

The rationale behind the strategy is that it is easier for teachers to:

- Reflect on attainment over the course of the year, comparing pieces of work by the same student over time;

- Compare attainment between year groups and ask: Has teaching improved? Are there different needs / interventions required in the current cohort compared with those of previous years?

- Get a snapshot of a student’s work.

The approach also allows the Lead Teacher and Curriculum Leader to spot-check progress and discuss successes or concerns with the class teacher.

As this is an emerging practice, the teachers are learning and adapting their practice to make it increasingly useful. The school’s findings include:

- The uniformity of the layout of the feed-forward sheets is helping students to understand the feed-forward process.

- Completion of the feed-forward sheets was originally time-consuming, but is now taking less time.

- In feed-forward lessons live modelling is being used rather than pre-prepared models.

- More prepared models are created in advance of assessment points as guidelines/reference tools for students.

- Prepared models are used after formal assessment as a comparison for students to use when self- or peer-assessing their performance.

- The specific focus in the feed-forward sheets on SPaG has been a helpful reminder to utilise micro-moments in lessons to consolidate technical skills.

- The teacher uses a ‘Students of Concern’ section (not visible to students) to provide additional support and interventions and to reflect on the success of any previous intervention.

- ‘Closing the Loop’ books have been introduced and have become a powerful tool in improving the value of assessment as a teaching and learning experience. These use a template for whole-class feedback and enable teachers to keep a track record of assessments and a track of their intentions in terms of adaptations to teaching as a result of assessment information about students’ knowledge, understanding and progress.

This is an example of assessment which is increasing the teacher’s criticality of the teaching and learning process and their expertise within this. The pupils benefit from the focused response to their work and the modelled practice. This exemplifies aspects of assessment used to achieve high-quality teaching:

“Rethinking assessment” across the NACE community

Other NACE member schools shared their experiences, including:

- A focus on understanding personal development – considering ways in which pupils’ overall experience and development can be better understood and supported, as part of assessment.

- Retrieval introduced as a core and explicit part of lesson sequences and schemes of work.

- The use of science practical activities linked to examination questions, to expose pupils to desirable difficulties. These reveal pupils’ knowledge and skills; support development and progress; and provide information needed to scaffold support at an individual level.

- Changes to reporting introduced to empower pupils, as well as informing leaders, teachers and parents.

- Developing the use of Rosenshine’s principles with a focus on higher-order questioning; this challenges more able pupils to think more deeply, extends their thinking, and has demonstrable benefits for other pupils in a mixed ability classroom.

- Models of excellence shared with pupils.

- Use of film resources and extended book study to encourage critical thinking and application of skills.

These varied approaches to assessment reflect the different contexts in which teachers work. They include assessment being used in three distinct ways:

Each of these has a place within teaching and learning. It is important that each type of assessment has a clear purpose and will impact effectively on the quality of teaching and the depth of learning. Pupils need to develop both within and beyond the content constraints of a curriculum. They need to learn about concepts as well as content. They need to understand what they are learning and how it links to other areas of learning. They need to develop cognition and cognitive strategies so that their learning is more useful to them both within school and in life.

The greatest gains can be achieved when the assessment itself is a part of learning and pupils have greater ownership of the process. As assessment practices develop within schools, the aim should be to upskill pupils so that they have the information they need to become self-regulating and to develop metacognitively.

Key factors for successful implementation

During the meetup, we observed that the schools with well-established assessment practice have introduced this within a whole-school ethos and strategy. Staff and pupils have a shared understanding of the use, purpose and benefits of the practice. Middle leaders are influential in the development of strategy, its consistency and the successful use within a subject specific context. Pupils are at the heart of the model and interact with assessment and feedback to improve their own learning. They develop cognitively and understand their own thinking and learning.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective assessment practices – including new initiatives, and well-established practices.

You may feel that some of the examples cited above are similar to practices in your own school, or you may have well-developed assessment models that would be of interest to others. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- Which area of assessment is used most effectively?

- What assessment practices are having the greatest impact on learning?

- How do teachers and pupils use the assessment information?

- How do you develop an understanding of pupils’ overall development?

- How do you use assessment information to provide wider experience and developmental opportunities?

- Is assessment developing metacognition and self-regulation?

Read more:

Plus: NACE is partnering with The Brilliant Club on a webinar exploring the links between metacognition and assessment, featuring practical examples from NACE member schools. Details coming soon – check our webinars page.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

collaboration

feedback

metacognition

pedagogy

progression

research

Permalink

| Comments (1)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

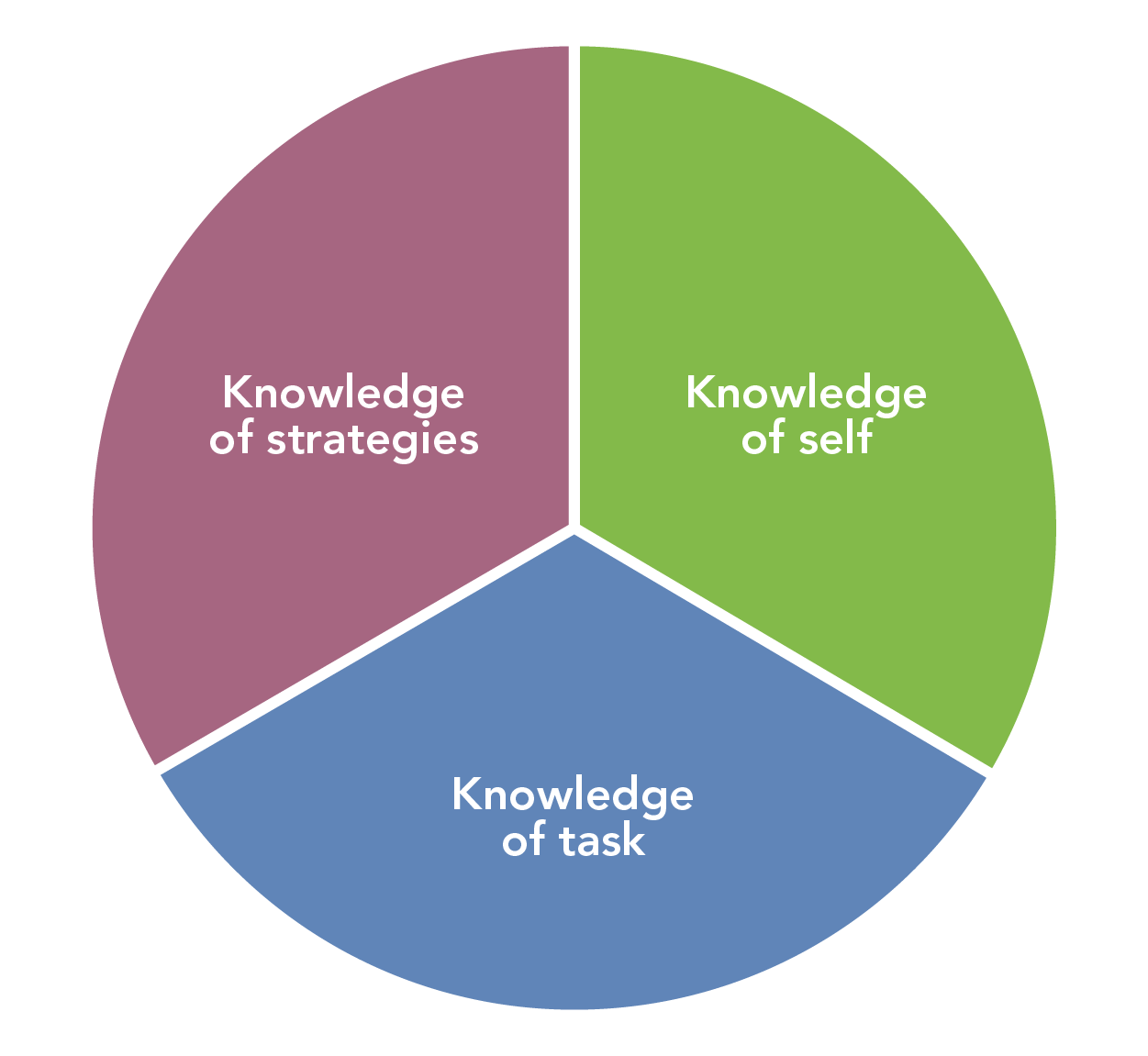

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 October 2021

|

NACE Research & Development Director Dr Ann McCarthy shares key principles for effective assessment planning and practice, within cognitively challenging learning environments.

Following two academic years of uncertainty and alternative arrangements for teaching and assessment, the conversation regarding testing and assessment has become increasingly important. Upon return to the routines of day-to-day classroom teaching, schools have had to find ways to assess knowledge, progress and understanding achieved through distance learning or redesigned classroom practices. For older pupils there has been a need to provide evidence to examination boards to secure grades and guarantee appropriate progression routes. This inherent need to provide checks and balances before pupils’ achievement is recognised can become a distraction from the art of teaching. In fact, Rimfield et al (2019) found a very high agreement between teacher assessments and exam grades in English, maths, and science.

- Could we examine less often and use classroom-based assessment more often?

- Should we rethink testing and assessment and their position in the learning process?

Testing vs assessment

The terms test and assessment are often used interchangeably, but in the context of education we need to recognise the difference. A test is a product which is not open to interpretation; it uses learning objectives and measures success achieved against these. Teachers use tests to measure what someone knows or has learned. These may be high-stakes or low-stakes events. High-stakes tests may lead to a qualification, grading or grouping, whereas low-stakes tests can support cognition and learning. Testing takes time away from the process of learning and as such testing should be used sparingly, when necessary and when it contributes significantly to the next steps in teaching or learning.

Assessment, by contrast, is a systematic procedure which draws on a range of activities or evidence sources which can then be interpreted. Regardless of the position teachers hold regarding the use of testing and examinations, meaningful assessment remains an essential part of teaching and learning. Assessment sits within curriculum and pedagogy, beginning with diagnostic assessment to plan learning which best reflects the needs of the learner. A range of formative assessment activities enable the teacher and pupils to understand progress, improve learning and adapt the learning to reflect current needs. Endpoint activities can be used as summative assessments to appreciate the degree to which knowledge has been acquired, alongside varied and complex ways in which that knowledge can be used.

Assessment might be viewed in three different ways: assessment of learning; assessment for learning; and assessment as learning. The choice of assessment practice will then impact on its use and purpose. Regardless of the process chosen and the procedures used, the teacher must remember that the value of the assessment is in the impact it has on pedagogy and practice and the resulting success for the pupils, rather than as an evidence base for the organisation.

NACE research has shown that cognitively challenging experiences – approaches to curriculum and pedagogy that optimise the engagement, learning and achievement of very able young people – will have a significant and positive impact on learning and development. But how can we see this working, and what role does assessment play? When planning for cognitively challenging learning, assessment planning should reflect the priorities for all other aspects of learning.

A strategic approach to assessment which supports cognitively challenging learning environments

When considering the place of assessment in education, teachers must be clear about:

- What they are trying to assess;

- How they plan to assess;

- Who the assessment is for;

- What evidence will become available;

- How the evidence can be interpreted;

- How the information can then be used by the teacher and the pupil;

- The impact the information has on the planned teaching and learning;

- The contribution assessment makes to cognition, learning and development.

Effective assessment is integral to the provision of cognitively challenging learning experiences. With careful and intentional planning, we can assess cognitive challenge and its impact, not only for the more able pupils, but for all pupils. Assessments are used to measure the starting point, the learning progression, and the impact of provision. When working with more able pupils, in cognitively challenging learning environments, the aim is to extend assessment practices to include assessment of higher-order, complex and abstract thinking.

When used well, assessment provides the teacher with a detailed understanding of the pupils’ starting points, what they know, what they need to know and what they have the potential to do with their learning. The teacher can then plan an engaging and exciting learning journey which provides more able pupils with the cognitive challenge they need, without creating cognitive overload.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has joined with others to recognise the importance of cognitive science to inform interventions and classroom practice. Spaced learning, interleaving, retrieval practice, strategies to manage cognitive load and dual coding all support cognitive development – but are dependent on effective assessment practices which guide the teaching and learning. The best assessment methods are those that integrate fully within curriculum teaching and learning.

Assessment and classroom management

It is important to place the learner at the centre of any curriculum plan, classroom organisation and pedagogical practice. Initially the teacher must understand the pupils’ strengths and weaknesses, together with the skills and knowledge they possess, before engaging in new learning. This understanding facilitates curriculum planning and classroom management, which have been recognised as essential elements of cognitively challenging learning. Often, learning time is lost through additional testing and data collection, but when working in cognitively challenging environments, planned learning should be structured to include assessment points within the learning rather than devising separate assessment exercises.

When assessing cognitively challenging learning, pupils need opportunities to demonstrate their abilities using analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. They must also show how they use their existing knowledge in new, creative, or complex ways, so questions might include opportunities to distinguish between fact and opinion, to compare, or describe differences. The problems may have multiple solutions or alternative methodologies. Alternatively, pupils may have to extend learning by combining information shared with the class and then adding new perspectives to develop ideas.

Assessing cognitively challenging learning will also include measures of pupils’ abilities to think strategically and extend their thinking. Strategic thinking requires pupils to reason, plan, and sequence as they make decisions about the steps needed to solve problems, and assessment should measure this ability to make decisions, explain solutions, justify their methods, and obtain meaningful answers. Assessments which demonstrate extended thinking will include investigations, research, problem solving, and applications to the real world. Pupils’ abilities to extend their thinking can be observed through problems with multiple conditions, a range of sources, or those drawn from a variety of learning areas. These problems will take pupils beyond classroom routines and previously observed problems. Assessment at this level does not depend on a separate assessment task, but teaching and learning can be reviewed and evaluated within the learning process itself.

Assessment in language-rich learning environments

Language-rich learning environments support cognitive challenge, high-order thinking and deep learning for more able pupils. It is therefore inevitable that language, questioning and dialogic discourse are key elements of formative assessment. They allow the teacher to assess learning in the moment and adjust the course of learning to adapt to the needs of the pupils.

Assessment in the moment, utilising effective questions and dialogic discourse, does not happen by accident, but is planned into the learning. When planning a lesson, the big ideas and essential questions which will expose, extend and deepen the learning are central to the planning and assessment. When posing the planned questions or creating opportunities for discourse, pupils need time to formulate their ideas and think before discussing the responses and extending learning with their own questions and ideas.

Within the language-rich classroom where an understanding of assessment is shared with pupils, the ownership of learning can be passed to them. The teacher will introduce the theory, necessary linguistic skills, and technical language, using these to model good questions and questioning techniques. More able pupils will develop their own oracy, language and questioning techniques, and then develop them together. Through regular practice and good classroom routines, pupils gain the confidence and skills to ask ‘big questions’ themselves and engage in dialogue. At this point, discussion and questioning becomes an effective mode of ongoing assessment. As pupils explain their thinking, misconceptions or gaps in knowledge will be exposed, allowing the teacher to assess, support learning, and encourage deeper thinking.

Priorities for effective assessment

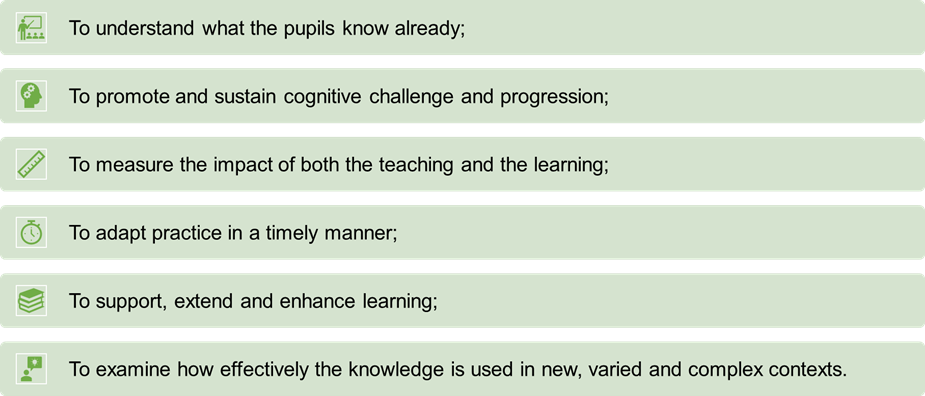

Within the classroom, the teacher needs to use assessment:

- To understand what the pupils know already;

- To promote and sustain cognitive challenge and progression:

- To measure the impact of both the teaching and the learning;

- To adapt practice in a timely manner;

- To support, extend and enhance learning;

- To examine how effectively the knowledge is used in new, varied and complex contexts.

Assessment has the potential to support pupils as learners as they will:

- Understand the nature and purpose of activities so that they can benefit from them;

- Appreciate the demands of learning;

- Engage in the learning journey;

- Develop their own cognitive skills and learning attributes;

- Take action to improve themselves;

- Take ownership of learning;

- Become increasingly autonomous and self-regulating.

Assessment is not a separate part of teaching and learning, but should be planned within the teaching. Assessment should not distract pupils from learning, and learning should not be framed to meet assessment criteria. Assessment is not about data gathering and organisational checks, but it should lead to enriched learning and refined practice with teachers and pupils working together to achieve an exciting learning environment.

What next?

This year, NACE is focusing on exploring effective assessment practices within Challenge Award-accredited schools. We hope that many schools will participate in this project, to provide evidence and share examples of effective assessment: what works, how, and why? By sharing our expertise with others we can move the conversation about assessment forwards and provide exciting and engaging learning for our pupils. To find out more or to express your school’s interest in contributing to this initiative, please contact communications@nace.co.uk

References

- Education Endowment Foundation (2021), Cognitive science approaches in the classroom (a review of the evidence)

- Rimfield. K, et.al. (2019), Teacher assessment during compulsory education are as reliable, stable, and heritable as standardized test scores. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 60(12) (1278-1288)

Read more:

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

myths and misconceptions

oracy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Sue Cowley,

11 November 2019

|

Alongside her webinar for NACE members, author and teacher trainer Sue Cowley shares five ways to ensure all learners are stretched and challenged – it’s differentiation, but not as you might expect!

It is tempting to think of differentiation as being about preparing different materials for different students – the classic ‘differentiation by task’. However, this type of differentiation is the most time-consuming for teachers in terms of planning. It can also be hard to create stretch through this approach, because it is difficult to pitch tasks at exactly the right level.

In reality, rather than being about preparing different activities, differentiation is a subtle skill that is not easily spotted ‘in action’. For instance, it might include adaptations to the teacher’s use of language, or ‘in the moment’ changes to a lesson, based on the teacher’s knowledge of individual learners.

1. Identify and account for prior knowledge

The highest-attaining students often have a great deal of knowledge about a diverse range of subjects – typically those areas of learning that fascinate them. They are likely to be autodidacts – reading widely around a favoured subject at home to find out more. Sometimes they will teach themselves new skills without any direct teacher input – for instance using YouTube to learn a language that is not on offer at school. At times, their level of knowledge or skill might outpace yours.

A key frustration for high attainers is the feeling that they are being taught things in school that they already know. Find ways to assess and ascertain the prior knowledge of your class before you start a new topic, and incorporate this information into your teaching. One simple strategy is to ask the class to write down the things they already know about a topic, before you begin to study it, and any questions that they want answered during your studies. Use these questions as a simple way to provide extension opportunities in lessons.

Where a learner has extensive prior knowledge of a topic, ask if they would like to present some of the knowledge they have to the class – this can help build confidence and presentational skills. It can also be useful for high-attaining learners to explain something they understand easily to a child who doesn’t ‘get it’ so quickly. The act of having to rephrase or reconceptualise something in order to teach it requires the learner to build empathy, understand alternative perspectives and think laterally.

2. Build on interests to extend

Where a high-attaining learner has an interest in a subject, they typically want to explore it far more widely than you have time to do at school. Encourage your high attainers to read widely around a subject outside of lesson time by providing them with information about suitable materials. A lovely way to do this is to give them suitable adult-/higher-level texts to read (especially some of your own books on a subject from home).

3. Inch wide, mile deep

When thinking about how to make an aspect of a subject more challenging, it is helpful to think about curriculum as being made up of both surface-level material and at the same time ideas that require much deeper levels of understanding. A useful metaphor is a chasm that must be crossed: those learners who struggle need you to build a bridge to help them to get over it. However, other students will be able to climb all the way down into the chasm to see what is at the bottom, before climbing up the other side.

For each area of a subject, consider what you can add to create depth. This might typically be about digging into an area more deeply, going laterally with a concept, or asking students to use more complex terminology to describe abstract ideas.

4. Use questioning techniques to boost thinking

The effective use of questions is vital for stretching your highest-attaining learners. Studies have shown that teachers tend to use far more closed questions than open ones, even though open-ended questions lead to more challenge because they require higher-order thinking.

Socratic questioning is a very useful way to increase the level of difficulty of your questions, because it asks learners to dig down into the thinking behind questions and to provide evidence for their answers. You can find out more about this technique at www.criticalthinking.org.

Another useful approach to questioning is a technique commonly used in early years settings, and known as ‘sustained shared thinking’ (for more on this, see this report on the Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years Project). In this approach, the child’s thinking is developed through the use of a ‘serve and return’ conversation in which open-ended questions are asked to build understanding.

5. Consider learner roles

Taking on a fresh role or perspective can really help to challenge our thinking. This is particularly so where we are asked to argue in favour of a viewpoint that we do not ourselves hold. This encourages the learner to build empathy with different viewpoints and to consider how a topic looks from alternative perspectives. A simple way to do this is by asking students to argue the opposite position to that which they actually hold, during a class debate.

Sue Cowley is an author, presenter and teacher educator. Her book The Ultimate Guide to Differentiation is published by Bloomsbury.

To find out more about these techniques for creating stretch and challenge, watch Sue Cowley's webinar on this topic (member login required).

Not yet a NACE member? Find out more, and join our mailing list for free updates and free sample resources.

Tags:

critical thinking

depth

differentiation

independent learning

progression

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Tracy Goodyear,

17 October 2019

|

Ahead of her workshop on this topic, NACE Associate and Head of English Tracy Goodyear shares three key considerations when planning a challenging KS3 English curriculum.

After getting the ‘new’ GCSEs firmly under our belts, schools and departments across the country are now being given the space to carefully consider the quality of the diet that all students receive in their secondary years.

For any department, reviewing the curriculum is an ongoing process. There’s no quick win or easy fix: it takes vision, clarity of thought and careful consideration – all whilst trying to navigate an educational, social and political landscape that is constantly shifting.

There’s an imperative to provide students with a curriculum that is enlightening, challenging and enriching. As emphasised in the current Ofsted education inspection framework, the curriculum should be ambitious and appropriate for all students. It’s vital that complex concepts or ideas are not ignored or brushed over, and that the expectation for success and high achievement is clear. A rising tide lifts all boats, after all.

Here are some key considerations, which we’ll explore in more detail during November’s workshop.

1. Start with the end in mind

When planning a new/revised curriculum, it’s imperative to consider what the end ‘product’ is likely to look like. In other words, ask yourselves: “At the end of Year 9, if we had given the students what they really need in our subject, what sort of behaviours, skills and attributes would our students display? How will we know we have been successful?”

This goes much further than hitting target grades; we have to think beyond that. As Christine Counsell has written, “If the curriculum itself is the progression model, then the numbers change their meaning.”

During a department meeting a couple of years ago, we brainstormed some ideas about our ‘finished article’ and came up with the following statements. These are core departmental values that drive our curriculum design and delivery.

As a result of learning in our department, students will:

- Be creative, articulate, imaginative learners, who are confident and secure in their opinions and thoughts;

- Be adaptable and flexible communicators in spoken and written word;

- Be unafraid to challenge complex ideas and material.

Our students will develop these dispositions and habits:

- Having a critical eye, so that they do not blindly accept things;

- They will openly welcome feedback, criticism and differing views and interpretations and not feel threatened by these;

- They will be skilled in planning, showing evidence of deep thinking;

- They will take risks, knowing that the learning they will experience is more valuable than the fear of failure;

- They will actively listen to and reason with the ideas and expertise of others;

- They will construct meaningful arguments, supporting their ideas with confidence and conviction.

They will experience learning activities that:

- Have pace, choice and challenge;

- Provide a healthy combination of independent and collaborative work;

- Give them ample opportunity to speak in front of others;

- Give them the time and space to write independently;

- Offer the choice and autonomy to self-select activities that best challenge their thinking and ability;

- Are well-planned by the teacher/ department, where activities have clear direction and purpose;

- Enable them to build a sophisticated vocabulary, consistently;

- Are academically rigorous and personally challenging.

2. Why this? Why now?

Once you have firm statements in place and a clear vision, you can start to consider the content and the validity of current content being delivered.

There are a whole host of questions to consider. Here are just a few:

- Is it important to you that students know the origins of stories/ origins of language?

- Is it important that students understand how or why contextual factors may influence our reception of a text?

- Is it important that they understand the five act structure of a Shakespeare play?

- Is it important that they are able to speak knowledgeably in a debate or a group discussion?

- Is it important to you that they can write with originality and flair?

Sitting as a team and deciding the answers to these sorts of questions is hugely valuable. It encourages teachers to share their particular passions and interests and leads to purposeful discussion about your curriculum offer. It’s important that you consider your own school’s context too – what is important here? What is it vital that we equip our students with? Vocabulary instruction? Cultural capital?

3. Timing is everything!

When planning a challenging curriculum, there is a temptation to hurtle through centuries of literature at a pace; the temptation to move on and cover as much content as possible seems attractive when teaching able young people. However, any successful curriculum needs to build in purposeful time to reflect – to recognise how concepts fit together as part of a much wider picture. All students require time to reflect on feedback (and time to act on it!), time for repetition, recall and a deeper investigation into a topic or idea.

Time is crucial in the breaking down of complex tasks, too. The EEF’s recent report Improving Literacy in Secondary Schools stresses the importance of modelling and scaffolding at all levels and dedicating curriculum time to this. Breaking tasks down (rather than simplifying them!) helps students to navigate their way through challenging tasks more effectively.

Consider the various demands on a student’s working memory when asked to write. How can teachers intervene to break down some of these processes to ensure working memories are not overwhelmed? How can we ensure that our curriculum plan incorporates the time and space to enable us to do this?

It’s not just the timing of what is being taught that’s key. Timely reflection for you and your team is also crucial. Wherever possible, make reviewing aspects of your curriculum part of your weekly/ fortnightly meetings. Speak about how students are progressing, where misunderstandings have arisen, how a scheme or unit of work needs to be adapted to suit the changing needs of the students. If all curriculum review does not take place while it’s still fresh, many of those smaller, nuanced observations about learning could be lost.

Enjoy the challenge!

Recommended reading:

- Turner, S. (2016), Secondary Curriculum and Assessment Design, Bloomsbury

- Myatt, M. (2018), The Curriculum: Gallimaufry to Coherence, John Catt

Ready to review your KS3 curriculum?

Join Tracy Goodyear’s workshop on 28 November: Leading curriculum change for more able learners in KS3 English

Tags:

curriculum

English

KS3

language

literacy

literature

progression

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Sarah Carpenter,

05 April 2018

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

Are your primary maths lessons too quiet? Ahead of her upcoming workshop on strengthening talk in primary maths, NACE associate Sarah Carpenter explains why effective discussions are key to deepening and extending learning in this core subject.

Often there’s an assumption that primary mathematics is about numbers, concepts, operations – and not about language. But developing the language of maths and the ability to discuss mathematical problems is essential to help learners explore, reflect on and advance their understanding.

This is true for learners of all abilities. But for more able mathematicians in particular, regular opportunities to engage in talk about maths can hold the key to deeper, more secure understanding. Moving away from independent, paper-based work and the tunnel-vision race to the answer, discussion can be used to extend and deepen learning, refocus attention on the process, and develop important analytical, reflective and creative skills – all of which will help teachers to provide, and learners to be ready for, the next challenge.

If you’re still not sure why or how to use discussions effectively in your primary mathematics lessons, here are five reasons that will hopefully get you – and your learners – talking about maths…

1. Spoken language is an essential foundation for development.

This is recognised in the national curriculum: “The national curriculum for mathematics reflects the importance of spoken language in pupils’ development across the whole curriculum – cognitively, socially and linguistically. The quality and variety of language that pupils hear and speak are key factors in developing their mathematical vocabulary and presenting a mathematical justification, argument or proof.” – National curriculum in England, Department for Education, 2013

Or to put this another way, when else would we expect learners to write something if they cannot say it? As Anita Straker writes: “Sadly, children are frequently expected to write mathematics before they have learned to imagine and to discuss, and those who do not easily make connections are offered more pencil and paper work instead of vital talk and discussion. Yet in other subjects it would be unthinkable to ask children to write what they cannot say.” – Anita Straker, Talking Points in Mathematics, 1993

2. Practice is needed for fluency…

… and fluency is what the new SATs expect – not only in numbers and operations, but in the language of mathematics as well. For mathematical vocabulary to become embedded, learners need to hear it modelled and have opportunities to practise using it in context. More able learners are often particularly quick to spot links between mathematical vocabulary and words or uses encountered in other spheres – providing valuable opportunities for additional discussion which can help to embed the mathematical meaning alongside others.

Free resource: For assistance in introducing the right words at the right stage to support progress in primary maths, Rising Stars’ free Mathematical Vocabulary ebook provides checklists for Years 1 to 6, aligned with the national curriculum for mathematics.

3. Discussion deepens and extends mathematical thinking.

The work of researchers including Zoltan Dienes, Jerome Bruner, Richard Skemp and Lev Vygotsky highlights the importance of language and communication in enabling learners to deepen and extend their mathematical thinking and understanding. Beyond written exercises, learners need opportunities to collaborate, explain, challenge, justify and prove, and to create their own mathematical stories, theories, problems and questions. Teachers can support this by modelling the language of discussion (“I challenge/support your idea because…”); using questioning to extend thinking; stimulating discussion using visual aids; and building in regular opportunities for paired, group and class discussions.

4. Talk supports effective assessment for learning.

More able learners often struggle to articulate their methods and reasoning, often replying “I did it in my head” or “I just knew”. This makes it difficult for teachers to accurately assess the true depth of their understanding. Focusing on developing the skills and language to discuss and explain mathematical processes helps teachers gain a clearer picture of each learner’s current understanding, and provide appropriate support and challenge. This will be an ongoing process, but a good place to start is with a “prior learning discussion” at the beginning of each new maths topic, allowing learners to discuss what they already know (or think they know) and what they want to find out.

5. Discussion helps higher attainers refocus on the process.

More able mathematicians often romp through learning tasks, focusing on reaching the answer as quickly as possible. Discussion can help them to slow down and refocus on the process, reflecting on their existing knowledge and understanding, taking on others’ ideas, and strengthening their conceptual understanding. This slowing down can be further encouraged by starting with the answer rather than the question; asking learners to devise their own questions; pairing learners to work collaboratively; using concept cartoons to prompt discussion of common misconceptions; and moving away from awarding marks only for the final solution.

During her 20-year career in education, Sarah has taken on a variety of roles in the early years and primary sectors, including classroom teaching, deputy headship and local authority positions. After a period as literacy and maths consultant for an international company, she returned to West Berkshire local authority, where she is currently school improvement adviser for primary maths and English. As a NACE associate, Sarah supports schools developing their provision for more able learners, leading specialised seminars, training days and bespoke CPD.

Tags:

assessment

language

maths

oracy

progression

questioning

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Tom Hills,

19 June 2017

Updated: 07 August 2019

|

Ynysowen Community Primary School is a successful primary school in Merthyr Tydfil, South Wales. The school is a Digital Pioneer School for the Welsh government and is a self-improving school. Ynysowen achieved its second NACE Challenge Award accreditation in May 2017.

Tom Hills, deputy headteacher and additional learning needs coordinator, gives an overview of the substantial work the school has done in the area of marking and feedback.

For a long time now schools have known that the feedback students receive is a vital component in moving learning forward. Some, like John Hattie, go as far as to say that it is the single most powerful modification we can make with regards to improving achievement, while the Education Endowment Foundation cites an average gain of up to eight months progress.

Couple this with the fact that marking features at or near the top of every survey conducted into teacher workload, and there are potentially huge benefits to all involved – if we get it right. And if we get it right, then we can lift the lid and remove some of the traditional glass ceilings that are in place in education, particularly for MAT learners.

“Non-negotiables” for marking and feedback

Based on this, we took the decision to review our already established good practice at Ynysowen Community Primary School. This led to us forming the following requirements as the basis for all subsequent work in this area.

We insisted that marking and feedback must:

- Be highly valued by the pupils;

- Be informative in terms of next steps;

- Impact upon pupil progress;

- Be highly valued by the staff;

- Be manageable;

- Put the onus on learners taking ownership and responsibility for their improvement and progress.

In order to achieve this, we set out the following non-negotiables.

- Every time a member of staff puts pen to paper to mark, learners will respond.

- When marking a body of text, marking will signpost learners to errors to correct via a coded marking system. (Code placed in the margin on the line where the error occurred.)

- When providing feedback by comment it will, where possible, contain an element of self-regulation, as this develops greater skills in self-evaluation or confidence to engage further on a task. Where this isn't appropriate, comments will focus on the process used in the task, or on the content of the completed work.

- Dedicated Improvement and Response Time (DIRT) must be used at the start of every lesson.

Impact and ongoing developments

The new coded marking was implemented in conjunction with DIRT and immediately had the desired impact of increasing pupil engagement with marking, and substantially reducing teacher workload. Within two weeks, staff reported learners beginning to use the coded mark system without prompting to self-assess and improve their work – before their teacher could mark it.

Over time, training was given to staff with regards to moving from task- and product-related comments to process and self-regulation. Initial baseline book review showed 65% of comments across KS2 were task- and product-related, 30% were related to process and only 5% self-regulation. After training, this moved to a much more balanced 40%, 35% and 25% respectively. Work is ongoing to further improve this swing.

When asked about marking and feedback, learners respond very positively. They talk with confidence about the purpose of marking and articulate clearly how it helps them move on in their learning; they love DIRT time. All teachers report a huge reduction in marking time.

This project has been the catalyst for more evidence-based reviews of practice. We have undertaken substantial work with regards to questioning and are currently taking some tentative steps in beginning to explore the area of metacognition for our older learners. Marking and feedback will be reviewed next year to look at how best to incorporate the features available in Google for Education (previously Google Apps for Education) – something the school uses extensively.

Making use of Google for Education

Google for Education offers facilities, the likes of which have never been readily available to schools in such a user-friendly way. Learners can use the apps to share their work and allow comments, so peers can suggest changes and leave feedback. This, however, need not be limited to within the classroom or even school – opening up all sorts of possibilities for school-to-school working across the world.

Then there’s Google Forms, which provides a different dimension to peer- and self-assessment. Theoretically learners could create their own form asking for feedback on specific things in their work and invite responses from people across the world.

Google Classroom makes collating learners’ work easy and quick and allows teachers to make and/or grade work and send it back to the pupil who can make alterations and re-submit. With the huge range of extensions and apps available in the Google Marketplace, this feedback could now take the form of saved audio clips – something that will make feedback even more detailed and accurate, with no time cost.

For those who prefer to use a pen to mark, there are now apps that allow the use of a stylus to physically mark pupils’ digital work. This is then converted to a .pdf and stored alongside the original work.

Given that Google for Education is continually updating and adding new features, the feedback functionality stands to get better and better, which can only be a good thing!

Tags:

assessment

feedback

independent learning

marking

progression

technology

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|