Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Lol Conway,

06 May 2025

|

Lol Conway, Curriculum Consultant and Trainer for the Design and Technology Association

Throughout my teaching, inclusivity has always been at the forefront of my mind – ensuring that all students can access learning, feel included, and thrive. Like many of my fellow teachers, at the start of my teaching career my focus was often directed towards supporting SEND or disadvantaged students, for example. I have come to realise, to my dismay, that more able students were not high up in my consideration. I thought about them, but often as an afterthought – wondering what I could add to challenge them. Of course, it should always be the case that all students are considered equally in the planning of lessons and curriculum progression and this should not be dictated by changes in school data or results. Inclusivity should be exactly that – for everyone.

True inclusivity for more able students isn’t about simply adding extra elements or extensions to lessons, much in the same way that inclusivity for students with learning difficulties isn’t about simplifying concepts. Instead, it’s about structuring lessons from the outset in a way that ensures all students can access learning at an appropriate level.

I realised that my approach to lesson planning needed to change to ensure I set high expectations and included objectives that promoted deep thinking. This ensured that more able students were consistently challenged whilst still providing structures that supported all learners. It is imperative that teachers have the confidence and courage to relentlessly challenge at the top end and are supported with this by their schools.

As a Design and Technology (D&T) teacher, I am fortunate that our subject naturally fosters higher-order thinking, with analysis and evaluation deeply embedded in the design process. More able students can benefit from opportunities to tackle complex, real-world problems, encouraging problem-solving and interdisciplinary connections. By integrating these elements into lessons, we can create an environment where every student, including the most able, is stretched and engaged. However, more often than not, these kinds of skills are not always nurtured at KS3.

Maximizing the KS3 curriculum

The KS3 curriculum is often overshadowed by the annual pressures of NEA and examinations at GCSE and A-Level, often resulting in the inability to review KS3 delivery due to the lack of time. However, KS3 holds immense potential. A well-structured KS3 curriculum can inspire and motivate students to pursue D&T while also equipping them with vital skills such as empathy, critical thinking, innovation, creativity, and intellectual curiosity.

To enhance the KS3 delivery of D&T, the Design and Technology Association has developed the Inspired by Industry resource collection – industry-led contexts which provide students with meaningful learning experiences that go beyond theoretical knowledge. We are making these free to all schools this year, to help teachers deliver enhanced learning experiences that will equip students with the skills needed for success in design and technology careers.

By connecting classroom projects to real-world industries, students gain insight into the practical applications of their learning, fostering a sense of purpose and motivation. The focus shifts from achieving a set outcome to exploring the design process and industry relevance. This has the potential to ‘lift the lid’ on learning, helping more able learners to develop higher-order skills and self-directed enquiry.

These contexts offer a diverse range of themes, allowing students to apply their knowledge and skills in real-world scenarios while developing a deeper understanding of the subject and industry processes. Examples include:

- Creating solutions that address community issues such as poverty, education, or homelessness using design thinking principles to drive positive change;

- Developing user-friendly, inclusive and accessible designs for public spaces, products, or digital interfaces that accommodate people with disabilities;

- Designing eco-friendly packaging solutions that consider materials, manufacturing processes, and end-of-life disposal.

These industry-led contexts foster independent discovery and limitless learning opportunities, particularly benefiting more able students. By embedding real-world challenges into the curriculum, we can push the boundaries of what students can achieve, ensuring they are not just included but fully engaged and empowered in their learning journey.

Find out more…

NACE is partnering with the Design & Technology Association on a free live webinar on Wednesday 4 June 2025, exploring approaches to challenge all learners in KS3 Design & Technology. Register here.

Tags:

access

cognitive challenge

creativity

design

enquiry

free resources

KS3

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

problem-solving

project-based learning

technology

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Charlotte Newman,

03 February 2025

|

Charlotte Newman shares five approaches to challenge learners in secondary school religious education (RE).

I want to start off by sharing my context with you as I believe this is important in what I have found works well in my school. I am a Head of Religious Education in a secondary school in Cambridgeshire. We are the largest school in the county and as a result we are truly comprehensive with a wide range of student abilities and backgrounds. At KS3, our classes are mixed ability and therefore, it can sometimes be difficult to stretch and challenge the most able when there may be other students in the group that need more support. At KS4, we set by ability with English, taking into account students’ target grades and KS3 data.

1. Teach to the top (and beyond!)

At KS3, we always aim to teach to the top and scaffold for those students who require more support. This ensures that every student in the class is challenged. Regular opportunities are built into the lessons to extend students’ thinking. This does not simply mean additional tasks, as this is something our students often get frustrated with – that ‘challenge’ equals ‘do more’. Instead, we will ask them to research something from the key stage above. For example, when teaching about the Four Noble Truths in Buddhism I might ask more able students to research the idea of dependent arising to better understand the Buddhist philosophy. At KS4, when teaching about Jesus’ resurrection to sets 1 and 2, I will bring in the views of Rudolf Bultmann and N.T. Wright on the idea of a metaphorical versus historical resurrection from KS5.

To ensure all teachers across the department are doing this effectively, we have spent CPD time mapping our KS3 against our GCSE specification to highlight the links we can make. We have done the same between our GCSE and A Level specifications. This has been particularly useful for those teachers who do not teach KS5, to increase their subject knowledge in order to stretch high ability students.

2. Encourage deep analytical thinking

In our school, we have employed PiXL ‘Thinking Harder’ strategies. These ensure students are showing their understanding of our topic by having to analyse the knowledge they have learnt. For example: which of a set of factors (Paul’s missionary journeys, martyrs, the Nicene Creed, Constantine) contributed most to the development of the early Church? They may order these and have to justify their choices.

We can also do this through questioning during philosophical debates to get students articulating their thoughts in a sophisticated argument. Examples include: “Why might that be the case?”; “Why is that significant?”; “What evidence do you have to support that view?”; “Can you add to what X just said?”

Additionally, it is important to ensure that students have the opportunity to engage with primary religious texts such as the Qur’an, as well as those from different scholars, such as Descartes’ Meditations. This enables them to develop their hermeneutical skills to really understand the text and its context, compare interpretations/perspectives of it and critically analyse it.

3. Allow opportunities for multidisciplinary connections

Religious education is a multidisciplinary subject. The Ofsted RE Review (2021) promotes “ways of knowing”, that students should understand how they know, through the disciplines of Theology, Philosophy and Social Sciences. You could arguably add others too: Psychology, History, Anthropology, etc.

When developing an enquiry question for a scheme of work, you may have in mind a particular discipline you wish the students to approach it from, for example exploring “What does it mean to be chosen by God?” using a theological method/tools to study the question from the perspective of Judaism. However, in order to stretch the most able students it would be fantastic if you gave them opportunities to think about this from a different ‘lens’. How might a Christian/Muslim approach this question? What would a philosophical/social scientist approach to this question look like?

4. Facilitate independent research projects

I currently run the NATRE Cambridgeshire RE Network Hub and so I regularly have the opportunity to meet up with other teachers/schools in my region. I was recently involved in a curriculum audit with other secondary teachers and I loved a scheme of work employed by one of my colleagues. Prior to starting the GCSE course, students are given the chance to choose a topic of interest to them within RE to conduct independent research and eventually present their findings. They are given a framework and some suggested ideas/resources to guide them as well as different ways in which they could present their research. This is a fantastic idea to stretch the most able as there is so much scope with this student-led project.

In my colleague’s school, all students have access to a handheld device, therefore IT is easily accessible to support this work. Teachers can easily share documents and links to students this way too. Unfortunately, this is not the case in my context and so wouldn’t be feasible, but I am in the process of thinking about how we could do something similar that works for us.

5. Promote independent learning outside of the classroom

In RE, we have the privilege of being able to teach about many real-world issues and ethical debates that students find fascinating. As a result, they often want to explore these further in their own time. Therefore, in my school we have compiled ‘Independent Study’ materials for each unit of both the GCSE and A Level courses.

At GCSE, we have compiled booklets where we suggest something to read, something to watch something to listen to, and something to research. These have enabled us to introduce A Level thinkers into the course and engage students with high-level thinking through The RE Podcast or Panspycast, for example. This is key as it piques students’ curiosity and promotes a real love of the subject.

At A Level, we provide students with university lectures (the University of Chester is great for this for RE) and debates between scholars on YouTube (e.g. Richard Dawkins and Alister McGrath on the relationship between religion and science). We then expect to see evidence of this further reading/research in their exam answers and their contributions to lessons.

About the author: Charlotte Newman is a Trust Lead for Religious Studies for Archway Learning Trust. She is on the Steering Group for the National Association for Teachers of RE (NATRE) and the Oak Academy Expert Group for RE. She is also a member of Cambridgeshire SACRE and has until recently led an RE local group. She has delivered much CPD on RE nationally.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

KS3

KS4

philosophy

project-based learning

questioning

religious education

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Oliver Barnes,

04 December 2024

|

Ollie Barnes is lead teacher of history and politics at Toot Hill School in Nottingham, one of the first schools to attain NACE Challenge Ambassador status. Here he shares key ingredients in the successful addition of a module on Hong Kong to the school’s history curriculum. You can read more in this article published in the Historical Association’s Teaching History journal.

When the National Security Law came into effect in Hong Kong, it had a profound and unexpected impact 6000 miles away, in Nottinghamshire’s schools. Important historical changes were in process and pupils needed to understand them. As a history department in a school with a growing cohort of Hong Kongers, it became essential to us that students came to appreciate the intimate historical links between Hong Kong and Britain and this history was largely hidden, or at least almost entirely absent, in the history curriculum.

But exploring Hong Kong gave us an opportunity to tell our students a different story, explore complex concepts and challenge them in new ways. Here I will outline the opportunities that Hong Kong can offer as part of a broad and diverse curriculum.

Image source: Unsplash

1. Tell a different story

In our school in Nottinghamshire, the student population is changing. Since 2020, the British National Overseas Visa has allowed hundreds of families the chance to start a new life in the UK. Migration from Hong Kong has rapidly increased. Our school now has a large Cantonese-speaking cohort, approximately 15% of the school population. The challenge this presented us with was how to create a curriculum which is reflective of our students.

Hong Kong offered us a chance to explore a new narrative of the British Empire. In textbooks, Hong Kong barely gets a mention, aside from throwaway statements like ‘Hong Kong prospered under British rule until 1997’. We wanted to challenge our students to look deeper.

We designed a learning cycle which explored the story of Hong Kong, from the Opium Wars in 1839 to the National Security Law in 2020. This challenged our students to consider their preconceptions about Hong Kong, Britain’s impact and migration.

2. Use everyday objects

To bring the story to life, we focused on everyday objects, which are commonly used by our students and could help to tell the story.

First, we considered a cup of tea. We asked why a drink might lead to war? We had already explored the Boston Tea Party, as well as British India, so students already knew part of this story, but a fresh perspective led to rich discussions about war, capitalism, intoxicants and the illegal opium trade.

Our second object was a book, specifically Mao’s Little Red Book. We used it to explore the impact of communism on China, showing how Hong Kong was able to develop separately, with a unique culture and identity.

Lastly, an umbrella. We asked: how might this get you into trouble with the police? Students came up with a range of uses that may get them arrested, before we revealed that possessing one in Hong Kong today could be seen as a criminal act. This allowed us to explore the protest movement post-handover.

At each stage of our enquiry, objects were used to drive the story, ensuring all students felt connected to the people we discussed.

Umbrella Revolution Harcourt Road View 2014 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

3. Keep it complex

In order to challenge our students, we kept it complex. They were asked to draw connections and similarities between Hong Kong and other former British colonies. We also wanted them to encounter capitalism and communism, growth and inequality. Hong Kong gave us a chance to do this in a new and fresh way.

Part of this complexity was to challenge students’ preconceptions of communism, and their assumptions about China. By exploring the Kowloon walled city, which was demolished in 1994, students could discuss the problems caused by inequality in a globalised capitalist city.

Image source: Unsplash

What next?

Our Year 9 students responded overwhelmingly positively. The student survey we conducted showed that they enjoyed learning the story and it helped them understand complex concepts.

Hong Kong offers curricula opportunities beyond the history classroom. In English, students can explore the voices of a silenced population, forced to flee or face extradition. In geography, Hong Kong offers a chance to explore urbanisation, the built environment and global trade.

Additional reading and resources

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

enquiry

history

KS3

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Zoe Enser,

15 November 2022

|

Zoe Enser, author of the new book Bringing Forth the Bard, shares eight key steps to help your students get to grips with (and enjoy!) the symbolic, allusive, musical, motif-packed language of Shakespeare.

The language of Shakespeare is perhaps one of the greatest barriers to most readers unfamiliar with its style, allusions and patterns. Shakespeare’s language can be something of a leveller as it doesn’t necessarily matter how proficient you are at reading generally; all students (and indeed many adults) will stumble across his words and need to deploy a different approach to reading than they are used to.

With so many finding the language problematic, there is a temptation to strip some of the complexity away; to focus instead on summaries or modern adaptations. There is, though, much to be gained by examining his words as they appear, much as you would when exploring a poem with your class.

Getting it can be really satisfying, and a key light-bulb moment for me at school was seeing how unpicking meaning could be looked at like a problem to be solved, much like solving equations in maths or finding the intricate pieces of a jigsaw. Most importantly perhaps is that his use of poetry, imagery and musicality frequently stays with us, and lines from Shakespeare that linger in our mind and our everyday language remain due to their crafting. We want to allow students to have that opportunity too.

Here are eight steps to bring Shakespeare’s language to life in your own classroom:

1. Begin by giving students an overview of the plot, characters and themes. Good quality performance, coupled with summary and questioning, will mean students arrive at language analysis ready to see how it relates to these bigger ideas. Audio readings of the plays can also be useful here to allow them to hear the language spoken and to model fluency.

2. Reassure students they won’t get it all immediately. Explain that the joy in studying Shakespeare’s language comes from the gradual understanding we gain and how it enriches our understanding, which is a process: one which even those familiar with his work will continue to go through. It is a process where we layer understanding, deepening each time we revisit it. If students have been used to exploring simpler texts this might be a challenge at first to consider this different approach, but model this for them, demonstrating how you can return to the same quote or extract again and again to delve deeper each time.

3. Look at short extracts and quotes from across a play or a range of texts to examine patterns and connections. Linger on individual words and then trace them as they are used elsewhere so students can notice where these links are and hypothesise as to why.

4. Use freely available searches to explore the frequency and location of key words and phrases. For example, a search on Open-Source Shakespeare reveals there are 41 direct references to ‘blood’ or ‘bloody’ in the play Macbeth, some of which are clustered within a few lines. This provides an opportunity to explore why this is the case and what Shakespeare was doing with these language choices. Equally, looking for references to the sun in Romeo and Juliet reveals 17 instances, and if then cross-referenced with light it brings forth a further 34 references, suggesting that there is a motif running through the text which demands further attention. Allowing students to explore this trail in their discussions and consider the prevalence of some words over others can reveal much about the themes Shakespeare was trying to convey too. For example, simply looking at the light and dark references in Romeo and Juliet enables students to see the binaries he has woven into the play to mirror the idea of conflict.

5. Discuss the imagery Shakespeare is trying to create with his language via pictures, selecting those which are most appropriate to convey his choices at different points. Thinking about how different audiences may respond to these is also a useful way to examine alternative interpretations of a single word, line or idea. This can also support learners with different needs as they have visual images to link to ideas, especially abstract ones, repeated throughout the text. This will provide them with something more concrete to link to the text and, as images are repeated throughout the narrative, can act as support for the working memory and enhance fluency of retrieval as they recognise the recurring images visually. This can be particularly useful for EAL students, supporting them to follow the plot and explore the patterns that emerge.

6. Teach aspects of metre (such as iambic and trochaic pentameter), ensuring students have lots of opportunities to hear the language spoken aloud so they can appreciate the musicality of the language and choice of form. Using methods such as walking the text, whereby students physically walk around the room whilst reading the text and responding to the punctuation, can be a powerful way to convey how a character feels at any given point. Lots of phrases, short clauses, or single syllable words can change the pace of the reading and we should model this and give students the opportunity to examine how this may then impact on performance. Long, languid sentences can create a different performance, and where the punctuation has finally landed in his work can reveal a lot about how a character or scene has been read. Try different ways of reading a single line to illustrate why we place emphasis on certain words and pauses at different points.

7. Read the text aloud together. As well as modelling reading for students, employing practices such as choral reading (where the class all read the text aloud together with you) or echo reading (where they repeat lines back) can be another way in which we remove the barriers the language can create. Students build confidence over time as the language becomes more familiar but also they do not feel so exposed as they are reading with the group, and not alone.

8. Let students play with and manipulate the language so they are familiar with it, and it doesn’t become a block to their interaction with the plays. Pre-teach the vocabulary, letting students consider words in isolation and explore quotes so that they don’t become overwhelmed at trying to interpret them. Even translating short phrases and passages can provide a useful coding activity which can support later analysis.

Zoe Enser was a classroom teacher for 20 years, during which time she was also a head of English and a senior leader with a responsibility for staff development and school improvement. This blog post is an excerpt from her latest book, Bringing Forth the Bard (Crown House Publishing). NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on this and all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website; for details log in to our member offers page.

Tags:

access

confidence

creativity

English

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

literacy

literature

oracy

pedagogy

reading

Shakespeare

vocabulary

writing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Chloe Bateman,

07 October 2022

|

Chloe Bateman is a Teacher of History at Maiden Erlegh School, a NACE Challenge Award-accredited school. Chloe has recently led the development of a whole-school oracy strategy. In this blog post, she shares some of the ways in which Maiden Erlegh has established and embedded a culture of oracy across the school to benefit all students, including the more able.

Oracy is ‘both everywhere and nowhere in a school’. At Maiden Erlegh, we realised that although plenty of classroom talk was taking place, opportunities for this could be ad hoc and students did not always recognise these as opportunities to develop oracy skills. At the same time, a significant number of students lacked the confidence to speak in front of larger groups and in more formal contexts, hindering their ability to engage with oracy-related elements of the taught curriculum and extracurricular activities. The national picture indicates that many schools experience similar challenges to developing student oracy and an oracy culture within the school.

Drawing on our experience, here are seven steps to establish a whole-school oracy culture:

1. Investigate your context to determine your priorities

Every school is different. Whilst the national trend shows a decline in oracy as a result of the Covid-19 lockdowns, every school will have different areas of strength and development in terms of the current oracy level of their students and their staff confidence in teaching to enhance oracy. Oracy too is itself a complex skill, made up not just of the verbal ability, but multiple components such as the physical and cognitive elements. To design a strategy which really works for your context, it is beneficial to gather student and staff voice to inform the precise nature of this. At Maiden Erlegh, we conducted quantitative and qualitative staff and student surveys, asking students to rate their level of confidence when communicating and why they may feel less confident in some areas than others. Staff were asked to share feedback on levels of student oracy and what support they would need to feel confident in developing an oracy culture in their own classrooms. From this data, we could easily identify clear priorities to be addressed through our strategy.

2. Secure buy-in from staff to secure buy-in from students

A strategy is only as effective as those who make it a reality on a day-to-day basis: the teaching staff. Our oracy work was launched via a training session to staff which centred on communicating the rationale for our new oracy focus. Here the student and staff voice surveys came into their own, enabling us to explain why we needed to develop oracy using the words of students and staff themselves and showing the overwhelming statistics. We also took time to share the wide-ranging holistic benefits of enhanced oracy for students, including for mental health, academic progress, and career opportunities. For maximum exposure, include students in the launch too and keep them as informed as you would do staff. We delivered assembles to all students sharing very similar messages to those shared during the staff launch, ensuring students were aware and engaged with our upcoming work.

3. Get staff and students on board with ‘quick wins’

It can be tempting to try to launch all strands of a strategy at once. However, this is unlikely to succeed in the long run as it risks overwhelming the very people you are attempting to get on board. Instead, generate enthusiasm and interest in oracy by sharing ‘quick wins’: low-preparation, high-impact activities to integrate more oracy opportunities into lessons. Staff and students loved our ‘no filler’ game in which students were challenged to answer questions or speak about a relevant topic without using filler words such as ‘erm’, ‘like’, and ‘basically’. As staff become more confident in creating their own oracy-based activities, encourage colleagues to share their own ‘quick wins’ via staff briefings and bulletins to build a culture of enthusiasm.

4. Give oracy an identity

Too often strategies and initiatives can be become lost in the organisational noise of a school and the day-to-day challenges and immediate priorities. Borrow from the world of marketing and promotions to create a clear identity for oracy by designing a logo and branding for your strategy using a simple graphic design website such as Canva. A catchy slogan can also help to build a ‘brand’ around the strategy and increase staff and student familiarity with the overall vision. At Maiden Erlegh School (MES), we use the slogan ‘MES Speaks Up!’ – a motto that has become synonymous with our vision for a culture of oracy across the school.

5. Establish and reinforce consistent high expectations for oracy

Most schools have shared and consistent high expectations for students’ literacy and numeracy, but how many have the same for oracy? Whilst many teachers will have high standards for communication in their classrooms, these will not have the same impact on students as if they are school-wide. At Maiden Erlegh, we established a set of ‘Guidelines for Great Oracy’, a clear list of five expectations including the use of formal vocabulary and projecting loudly and clearly. These expectations were launched to both staff and students and all classrooms now display a poster to promote them. The key to their success has been clearly communicating how easily these can be embedded into lessons, for example as success criteria for self- and peer-assessment during oracy-based activities such as paired or group discussions.

6. Create a shared understanding that oracy will enhance the existing curriculum

With so many competing demands on a classroom teacher’s time, it is easy to see why strategies and initiatives which feel like ‘add-ons’ can miss the mark and fail to become embedded in a school’s culture. Central to the success of our oracy strategy has been raising staff, student, and parent awareness that a focus on oracy will enhance our existing curriculum, rather than distract from it. From the very beginning, staff have been encouraged to return to existing lesson activities which cover existing content and adapt these with oracy in mind. In History, for example, an essay was preceded by a parliamentary debate to help students to construct convincing arguments, whilst in Maths students developed complex verbal explanations for the processes they were performing rather than simply completing calculations. Not only do such activities support oracy skills, but they demonstrate the inherent importance of oracy across the curriculum and allow departments to better meet their own curricular aims.

7. Keep the momentum going with high-profile events

As with any new strategy or initiative, we realised that after the initial enthusiasm there was a potential for staff and students to lose interest as the year wore on. To combat this, we developed high-profile events to return oracy to centre stage and engage students and staff alike. In May, we held MES Speaks Up! Oracy Month – a month of activities focused on celebrating oracy and its importance across all aspects of school life. In form time, students were challenged to discuss a topical ‘Question of the Day’ from our ‘Discussion Calendar’ to get them communicating from the moment they arrived in school. Every subject dedicated at least one lesson during the month to an activity designed to develop and celebrate oracy skills, including public speaking, debating, and presenting. Outside of lessons, students from each year group participated in a range of extracurricular parliamentary debates on issues relevant to their age group. All of these activities were widely promoted via our school social media to generate a buzz around oracy with our parents and guardians.

References

Interested in developing oracy within your own school?

• Join our free member meetup on this theme (18 October 2022)

• Join this year’s NACE R&D Hub with a focus on oracy for high achievement (first meeting 20 October 2022)

• Explore more content about oracy

Tags:

campaigns

confidence

curriculum

enrichment

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

oracy

pedagogy

personal development

questioning

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Howell's School, Llandaff,

20 June 2022

|

Sue Jenkins, Head of Years 10 and 11, and Hannah Wilcox, Deputy Head of Years 10 and 11, share five reasons they’ve found The Day an invaluable resource for tutor time activities.

Howell’s School, Llandaff, is an independent school in Cardiff which educates girls aged 3-18 and boys aged 16-18. It is part of the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST).

The Day publishes daily news articles and resources with the aim of help teachers inspire students to become critical thinkers and better citizens by engaging their natural curiosity in real-world problems. We first came across it as a library resource and recognised its potential for pastoral activities when the length of our tutor time sessions was extended to allow more discussion time and flexibility in their use.

Post-Covid, it has never been more important to promote peer collaboration, discussion and debate in schools. There is an ever-increasing need for students to select, question and apply their knowledge when researching; it has never been more important for students to have well-developed thinking and analytical skills. We find The Day invaluable in helping us to prompt students to discuss and understand current affairs, and to enable those who are already aware to extend and debate their understanding.

Here are five key pastoral reasons why we would recommend subscribing to The Day:

1. Timely, relevant topics throughout the year

You will always find a timely discussion topic on The Day website. The most recent topics feature prominently on the homepage, and a Weekly Features section allows you to narrow down the most relevant discussion topic for the session you are planning. Assembly themes, such as Ocean Day in June, are mapped across the academic year for ease of forward planning. We particularly enjoyed discussing the breakaway success of Emma Raducanu in the context of risk-taking, and have researched new developments in science, such as NASA’s James Webb telescope, in the week they have been launched.

2. Supporting resources to engage and challenge students

The need to involve and interest students, make sessions straightforward for busy form tutors, and cover tricky topics, combine to make it daunting to plan tutor time sessions – but resources linked to The Day’s articles make it manageable. Regular features such as The Daily Poster allow teachers to appeal to all abilities and learning styles with accessible and interesting infographics. These can also be printed and downloaded for displays, making life much easier for academic departments too. One of the best features we’ve found for languages is the ability to read and translate articles in target languages such as French and Spanish. Reading levels can be set on the website for literacy differentiation, and key words are defined for students to aid their understanding of each article.

3. Quick PSHE links for busy teachers

Asked to cover a class at the last minute? We’ve all been there! With The Day, you are sure to find a relevant subject story to discuss within seconds, and, best of all, be certain that the resources are appropriate for your students. With our Year 10 and 11 students, we have covered topics such as body image with the help of The Day by prompting discussion of Kate Winslet’s rejection of screen airbrushing. Using articles is particularly useful with potentially difficult or emotive issues where students may be more able to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of certain attitudes by looking at news events, detaching themselves from but also gaining insight about the personal situations they may be experiencing. The PSHE programme is vast; it is great to use The Day to plan tutor time sessions and gives us the opportunity to touch on a wide range of issues relatively easily.

4. Motivational themes brought to life through real stories

We have also found The Day’s articles useful for providing examples of motivational themes for our year groups. The Themes Calendar is particularly useful here; for example, tutor groups discussed the themes of resilience and diversity using the article on Preet Chandi’s trek to the South Pole. If you’re looking for assembly inspiration, The Day is a great starting point.

5. Develop oracy, thinking and research skills through meaningful debate

Each article has suggested tasks and discussion questions which we have found very useful for planning tutor time activities which develop students’ oracy, thinking and research skills. The Day promotes high-level debates about environmental, societal and political issues which students are keen to explore. One recent example is the discussion of privacy laws and press freedom prompted by the article about Rebel Wilson’s forced outing by an Australian newspaper. Activities can be easily adapted or combined to promote effective discussion. ‘Connections’ articles contain links to similar areas of study, helping teachers to plan and students to see the relevance of current affairs.

Find out more…

NACE is partnering with The Day on a free live webinar on Thursday 30 June, providing an opportunity to explore this resource, and its role within cognitively challenging learning, in more detail. You can sign up here, or catch up with the recording afterwards in our webinars library (member login required).

Plus: NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to The Day. For details of this and all current member offers, take a look at our member offers page (login required).

Tags:

critical thinking

enrichment

independent learning

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

libraries

motivation

oracy

personal development

questioning

research

resilience

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Kate Hosey,

17 June 2022

|

Kate Hosey, Assistant Headteacher at Ferndown Upper School, shares lessons learned from an intervention to develop students’ metacognitive skills in the classroom – emphasising the importance of focusing on process, not task, when modelling.

Metacognition is not new; many of us use it without realising in our classrooms every day. Those questions we ask students about what they understand about a topic, or why they have come to the conclusion they have, as well as the use of retrieval practice, interleaving and knowledge organisers, are all based on a metacognitive understanding of the process of learning. The EEF’s Teaching and Learning Toolkit suggests that metacognition can raise the attainment of pupils by seven months, which is justification in itself for focusing on it in school.

For a while now I have been conscious that the students at my school are generally well-behaved and want to do well, but that a number of them find it hard to motivate themselves to be more active in their learning. This has come out in areas like homework and attitudes to learning, where often the same students are receiving sanctions regularly for not doing homework.

We developed an intervention based around teaching metacognition skills with the aim of empowering the students to take control of their learning. Teaching students to be more aware of how they learn will enable them to find links and develop strategies to become more independent and more in control.

Research suggests that most classrooms are set up to promote metacognition in teachers rather than students; a bit like having a personal trainer who says “I’m going to help you meet all your fitness goals – now sit back while I lift all the weights”. We need to shift responsibility; for years our students have internalised the idea that students are supposed to get answers from teachers, and so stop trying to find out for themselves – they assume the person in charge of their learning is someone other than them. A great teacher teaches as little as possible, while modelling behaviours of how to figure something out.

We decided to focus on three key areas:

- Promote purposeful dialogue about thinking in the classroom;

- Provide challenge;

- Model metacognitive skills – talk about thinking and how as a teacher we think things through.

The first two areas were fairly straightforward to implement. Teachers needed to be more aware of their own language and questioning in their classrooms and could use the strategies suggested by websites such as metacognition.org.uk to support them if they wished.

Number 3, however, was a bit trickier. We were good at breaking down a task into manageable stages for students and scaffolding their writing, but found that next time we asked them complete a similar activity, they had forgotten how to do it. Looking at an exam-style question for the fifth time and saying to the class “so what do we do first?” we were met with blank faces and puzzled silence. In verbalising our own thought processes we allow the students to see how to work out what to do, which eventually will enable them to use the strategy for any assessment they are asked to complete.

Here is a modelling example from history (although other subjects would be similar!). It is important to focus on the modelling of process – not modelling the task:

| What to do: modelling process |

What to avoid: modelling task |

|

“The first thing I think about when I’m about to start writing is ‘how can I make sure I directly answer this question?’ One simple way I know I can do that is to pick out words from the question to include in my first sentence, because I know if I get the first sentence right then my paragraph will be well focused.”

The teacher writes the first sentence.

|

“The first sentence of our answer always needs to include words from the question so that we focus our answer in the right area.”

The teacher writes the first sentence.

|

|

“Next I’m thinking ‘what do I know about this topic that is relevant to the point I’ve just made?’ Here I tend to pause for a bit to run through the knowledge I’ve got and make some choices about which pieces of evidence will best support my point. Once I’ve made a decision I start writing again.”

Teacher writes second sentence, describing key historical facts connected to the point.

|

“Next I need to include key pieces of precise evidence that will support my point.”

Teacher writes second sentence, describing key historical facts connected to the point.

|

In verbalising their thought processes in this way, teachers are showing students how to think about their learning. They are giving students knowledge of the process so that they can also use it when approaching assessments, which of course they will have to do on their own eventually.

Having worked on this for two terms, we discussed how well we thought the students had taken on board the skills we were teaching them and how it had impacted on their progress and homework sanctions. The data showed they had an improvement in P8 score, on average of +0.40 (over half a grade) and 40% students had received fewer sanctions for no homework.

Of course, it is difficult to measure whether or not the strategies we employed directly impacted on students’ progress – it could also have been down to other influencing factors both in and out of school. However, the soft data gathered from staff and student surveys showed an improvement in students’ own understanding of metacognition as well as staff willingness and ability to use metacognitive approaches in their own teaching. Anecdotally there was a sense that lessons were more focused and students more engaged as a result of the attention being paid to metacognition in the classroom.

References

Tags:

cognitive challenge

feedback

KS3

KS4

language

metacognition

motivation

pedagogy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Tom Stewart,

01 April 2022

|

Tom Stewart, Head of History at Maiden Erlegh School, sets out tangible strategies that he and his department take when challenging more able students in history lessons.

History at secondary school level is a subject that, from my experience, is usually taught in mixed ability classes. Due to this, and to rightfully ensure the progress of those who struggle with literacy and require further support, lessons can tend to be pitched towards the middle with scaffolding and structure in place to help those struggling. The potential problem with this approach is that it risks neglecting the more able students and those who need to be challenged or stretched (or whichever phrase is used in your setting), to reach their potential. I hope this blog post will give you some ideas to take away to challenge the more able learners in your history lessons.

#1. Short-term: Questioning

A simple and easy way to challenge those more able students is through effective use of the questioning they face in a lesson. I imagine most teachers know about open and closed questions and how the latter can limit students to a one-word answer, whilst the former can require students to elaborate in more depth. Therefore, the answer the students give can often depend on how much thought has gone into the question asked.

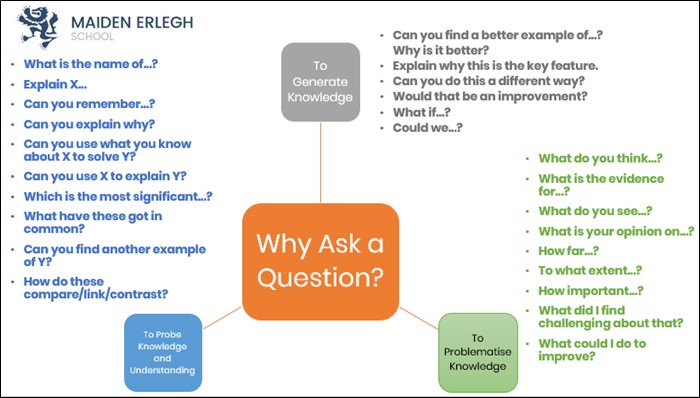

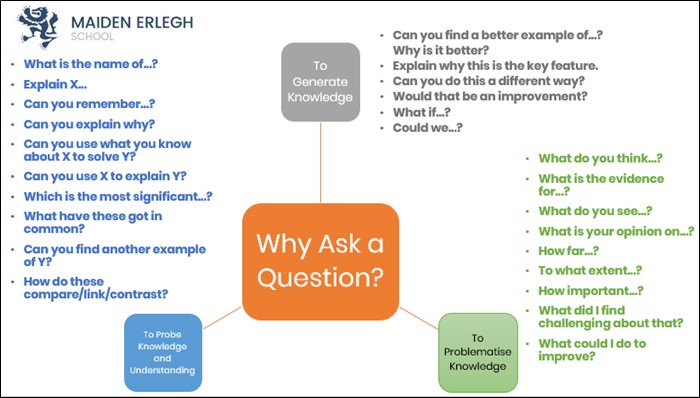

It is important to consider why a teacher is asking a question and this can then be applied to challenging the more able students by asking a variety of questions for different reasons. In a recent CPD session at my school, delivered by two excellent Assistant Headteachers, Rob Buck and Ben Garner, this principle, with some examples, was shared with staff (Figure 1). It reminded myself and my department to think carefully about the questioning we carried out and to target those more able students, whether they be in Year 7, Year 10 or Year 13.

Figure 1

#2. Medium-term: Widen their perspectives

More able students are often characterised by a curious and inquisitive nature. To support this, it is important to not be overly selective with the history shared with students, but find opportunities to reveal more of the story. Students of all abilities enjoy learning knowledge that isn’t necessarily vital to the topic – knowledge that Bailey-Watson calls ‘hinterland’ knowledge – and we should be willing to share with students more of the big picture in order to widen their perspectives and improve their historical thinking.

Homework can be an outlet for this; the previously mentioned Bailey-Watson and Kennet launched their ‘meanwhile, elsewhere…’ project (Figure 2) with the explicit intention of ‘expanding historical horizons’. Used effectively, this is a strategy that challenges the more able students to make those links between what they know and what they are yet to know.

Figure 2

#3. Long-term: Enquiry-based topics

History lends itself to a wealth of interesting topics. This selection narrows at GCSE and A-Level as specifications force middle leaders to select one topic and not another. However, at Key Stage 3, there is normally more choice and also an opportunity to challenge more able students. We have found evolving already-established topics – or creating new ones where time allowed and necessity demanded – into enquiry-based ones supports more able students by forcing them to ‘think hard’.

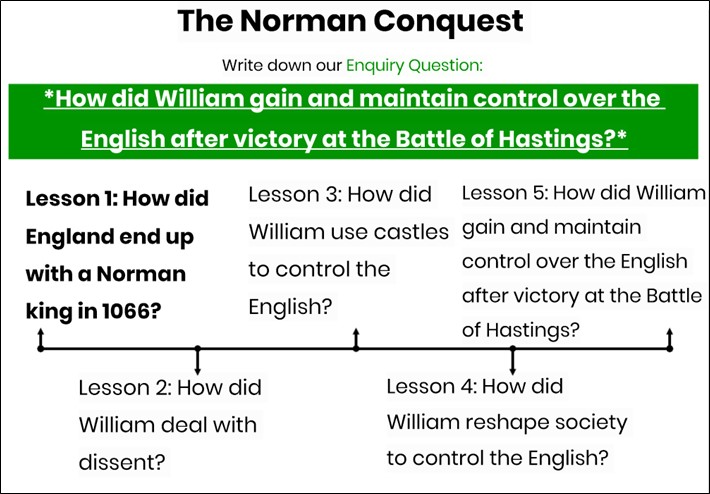

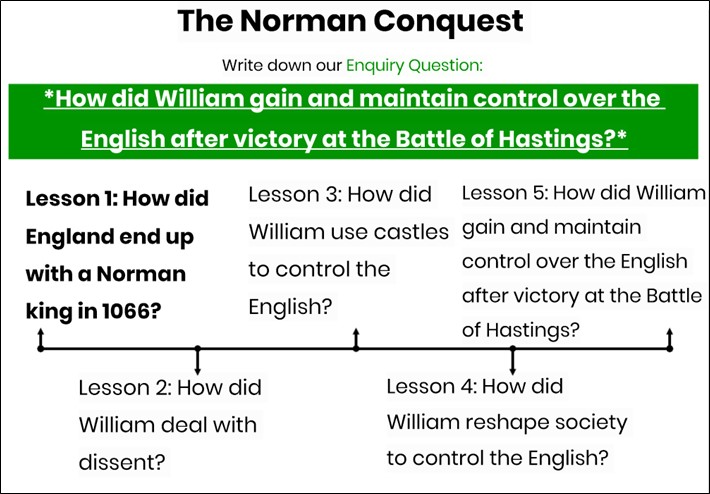

Our topic on the Norman Conquest, an event described by Peter Rex as ‘the single most important event in English history’ avoids a simpler narrative of events and instead forces students, especially the more able, to consider how King William managed not only to gain control but maintain it after the Battle of Hastings (Figure 3). This topic was designed by my fantastic colleague, Chloe Bateman, and this approach provides all students with an overview of where the lesson and topic fits in and also encourages deep thinking about the answer to the enquiry question before it has even been covered.

Combined with sharing demanding texts with students in lessons and homework that relates directly to the enquiry question, whilst extending their knowledge and understanding even further, enquiry-based topics can prove very effective at challenging more able students in secondary history.

Figure 3

There are plenty of strategies out there and there are more that I use and could have shared with you, but here are three that you could look to introduce to your setting. The important point is to be mindful about the experience more able students get in our classrooms. Do they feel challenged? Would you in their shoes? If not, then be active in doing something about it.

References

- Bailey-Watson, W. and Kennett, R. (2019). '"Meanwhile, elsewhere…": Harnessing the power of community to expand students’ historical horizons’, Teaching History, 176.

- https://meanwhileelsewhereinhistory.wordpress.com/

- Paramore, J. (2017). Questioning to Stimulate Dialogue, in Paige R., Lambert, S. and Geeson, R. (eds), Building Skills for Effective Primary Teaching, London: Learning Matters.

- Rex, P. (2011). 1066: A New History of the Norman Conquest, Amberley Publishing.

Read more:

Tags:

enquiry

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elena Stevens,

28 March 2022

Updated: 24 March 2022

|

History lead and author Elena Stevens shares four approaches she’s found to be effective in diversifying the history curriculum – helping to enrich students’ knowledge, develop understanding and embed challenge.

Recent political and cultural events have highlighted the importance of presenting our students with the most diverse, representative history curriculum possible. The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the tearing down of Edward Colston’s statue the following month prompted discussion amongst teachers about the ways in which we might challenge received histories of empire, slavery and ‘race’; developments in the #MeToo movement – as well as instances of horrific violence towards women – have caused many to reflect on the problematic ways in which issues of gender are present within the curriculum. Diversification, decolonisation… these are important aims, the outcomes of which will enrich the learning experiences of all students, but how can we exploit the opportunities that they offer to challenge the most able?

At its heart, a more diverse, representative curriculum is much better placed to engage, inspire and include than one which is rooted in traditional topics and approaches. A 2018 report by the Royal Historical Society found that BAME student engagement was likely to be fostered through a broader and more ‘global’ approach to history teaching, whilst a 2014 study by Mohamud and Whitburn reported on the benefits of – in Mohamud and Whitburn’s case – shifting the focus to include the histories of Somali communities within their school. A history curriculum that reflects Black, Asian and ethnic minorities, as well as the experiences of women, the working classes and LGBT+ communities, is well-placed to capture the interest and imagination of young people in Britain today, addressing historical and cultural silences. There are other benefits, too: a more diverse offering can help not only to enrich students’ knowledge, but to develop their understanding of the historical discipline – thereby embedding a higher level of challenge within the history curriculum.

Below are four of the ways in which I have worked to diversify the history schemes of work that I have planned and taught at Key Stages 3, 4 and 5 – along with some of the benefits of adopting the approaches suggested.

1: Teach familiar topics through unfamiliar lenses

Traditionally, historical conflicts are taught through the prism of political or military history: students learn about the long-term, short-term and ‘trigger’ causes of the conflict; they examine key ‘turning points’; and they map the war’s impact on international power dynamics. However, using a social history approach to deliver a scheme of work about, for example, the English Civil War, complicates students’ understanding of the ‘domains’ of history, shifting the focus so that students come to appreciate the numerous ways in which conflict impacts on the lives of ‘ordinary’ people. The story of Elizabeth Alkin – the Civil War-era nurse and Parliamentary-supporting spy – can help to do this, exposing the shortfalls of traditional disciplinary approaches.

2: Complicate and collapse traditional notions of ‘power’

Exam specifications (and school curriculum plans) are peppered with influential monarchs, politicians and revolutionaries, but we need to help students engage with different kinds of ‘power’ – and, beyond this, to understand the value of exploring narratives about the supposedly powerless. There were, of course, plenty of powerful individuals at the Tudor court, but the stories of people like Amy Dudley – neglected wife of Robert Dudley, one of Elizabeth I’s ‘favourites’ – help pupils gain new insight into the period. Asking students to ‘imaginatively reconstruct’ these individuals’ lives had they not been subsumed by the wills of others is a productive exercise. Counterfactual history requires students to engage their creativity; it also helps them conceive of history in a less deterministic way, focusing less on what did happen, and more on what real people in the past hoped, feared and dreamed might happen (which is much more interesting).

3: Make room for heroes, anti-heroes and those in between

It is important to give the disenfranchised a voice, lingering on moments of potential genius or insight that were overlooked during the individuals’ own lifetimes. However, a balanced curriculum should also feature the stories of the less straightforwardly ‘heroic’. Nazi propagandist Gertrud Scholtz-Klink had some rather warped values, but her story is worth telling because it illuminates aspects of life in Nazi Germany that can sometimes be overlooked: Scholtz-Klink was enthralled by Hitler’s regime, and she was one of many ‘ordinary’ people who propagated Nazi ideals. Similarly, Mir Mast challenges traditional conceptions of the gallant imperial soldiers who fought on behalf of the Allies in the First World War, but his desertion to the German side can help to deepen students’ understanding of the global war and its far-reaching ramifications.

4: Underline the value of cultural history

Historians of gender, sexuality and culture have impacted significantly on academic history in recent years, and it is important that we reflect these developments in our curricula, broadening students’ history diet as much as possible. Framing enquiries around cultural history gives students new insight into the real, lived experiences of people in the past, as well as spotlighting events or time periods that might formerly have been overlooked. A focus, for example, on popular entertainment (through a study of the theatre, the music hall or the circus) helps students construct vivid ‘pictures’ of the past, as they develop their understanding of ‘ordinary’ people’s experiences, tastes and everyday concerns.

There is, I think, real potential in adopting a more diversified approach to curriculum planning as a vehicle for embedding challenge and stretching the most able students. When asking students to apply their new understanding of diverse histories, activities centred upon the second-order concept of significance help students to articulate the contributions (or potential contributions) that these individuals made. It can also be interesting to probe students further, posing more challenging, disciplinary-focused questions like ‘How can social/cultural history enrich our understanding of the past?’ and ‘What can stories of the powerless teach us about __?’. In this way, students are encouraged to view history as an active discipline, one which is constantly reinvigorated by new and exciting approaches to studying the past.

About the author

Elena Stevens is a secondary school teacher and the history lead in her department. Having completed her PhD in the same year that she qualified as a teacher, Elena loves drawing upon her doctoral research and continued love for the subject to shape new schemes of work and inspire students’ own passions for the past. Her new book 40 Ways to Diversify the History Curriculum: A practical handbook (Crown House Publishing) will be published in June 2022.

NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website; for details of this and all NACE member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

References

Further reading

- Counsell, C. (2021). ‘History’, in Cuthbert, A.S. and Standish, A., eds., What should schools teach? (London: UCL Press), pp. 154-173.

- Dennis, N. (2021). ‘The stories we tell ourselves: History teaching, powerful knowledge and the importance of context’, in Chapman, A., Knowing history in schools: Powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge (London: UCL Press), pp. 216-233.

- Lockyer, B. and Tazzymant, T. (2016). ‘“Victims of history”: Challenging students’ perceptions of women in history.’ Teaching History, 165: 8-15.

More from the NACE blog

Tags:

critical thinking

curriculum

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Kyriacos Papasavva,

26 August 2021

|

Kyriacos Papasavva, Head of Religious Studies at St Mary’s and St John’s (SMSJ) CE School, shares three ways in which the school seeks to nurture a love of learning – for students and staff alike.

Education becomes alive when educators and students love what they do. This is, I think, the whole point of teaching: to inspire a love of learning among those we teach. Love, however, is not something that can be forced. Instead, it is ‘caught’.

For such a desire to develop in our pupils, there must be a real freedom in the learning journey. From the teacher’s perspective, this can be a scary prospect, but we must remember that a teacher is a guide only; you cannot force children to learn, but it is genuinely possible to inspire among pupils a love of learning. To enable this, we should ask ourselves: to what extent do we as teaching practitioners allow the lesson to go beyond the bulwark we impose upon any limited, pre-judged ‘acceptable range’? How do we allow students to explore the syllabus in a way that is free and meaningful to the individual? If we can find a way to do this, then learning really becomes magical.

While there is the usual stretch and challenge, meta-questions, challenge reading, and more, the main thrust of our more able provision in the religious studies (RS) department at SMSJ is one which encourages independent research and exploration. Here are several of the more unique ways that we have encouraged and challenged our more able students in RS and across the school, with the aim of developing transferable skills across the curriculum and inspiring a love of learning amongst both students and staff.

1. Papasavitch (our very own made-up language)

We had used activities based on Jangli and Yelrib, made-up languages used at Eton College, to stretch our pupils and give them exciting and unique learning opportunities. These activities were so well received by our pupils; they wanted more. So we developed ‘Papasavitch’, our very own made-up language.

This is partly what I was referring to earlier: if you find something students enjoy doing, give them a space to explore that love; actively create it. To see if your pupils can crack the language, or have a go yourself, try out this sample Papasavitch activity sheet. 2. The RS SMSJ Essay Writing Competition (open to all schools)

In 2018, SMSJ reached out to a number of academics at various universities to lay the foundations of what has become a national competition. We would like to thank Professor R. Price, Dr E. Burns, Dr G. Simmonds, Dr H. Costigane, Dr S. Ryan and Dr S. Law for their support.

Biannually, we invite students from around the UK (and beyond) to enter the competition, which challenges them to write an essay of up to 1,000 words on any area within RS, to be judged by prestigious academics within the field of philosophy, theology and ethics. While we make this compulsory for our RS A-level pupils, we receive copious entries from students in Years 7-11 at SMSJ, and beyond, owing to the range of possible topics and broad interest from students. Hundreds of students have entered to date, including those from top independent and grammar schools around the UK. (Note: submissions should be in English, and only the top five from each school should be submitted.)

You can learn more about the competition – including past and future judges, essay themes, examples of past entries, and details of how to enter – on the SMSJ website. 3. Collaboration and exploration – across and beyond the school

The role of a Head of Department (HoD), as I see it, is to actively seek opportunities for collaboration and exploration – within the school family and beyond into the wider subject community, as well as among the members of the department. At SMSJ, this ethos is shared by HoDs and other staff alike and expressed in a number of ways.

Regular HoD meetings to discuss and seek opportunities for implementing cross-curricular links are a must, and have proven fruitful in identifying and utilising overlap in the curriculum. Alongside this, we run a Teacher Swaps programme where teachers can study each other’s subjects in a tutorial fashion, naturally creating an awareness and understanding of other subjects.

The Humanities Faculty offers a ‘Read Watch Do’ supplementary learning programme for each year group, which runs alongside regular home learning tasks. The former also supports other departments through improved literacy, building cultural capital and exploration via the independent learning tasks.

Looking beyond the school, our partnerships with the K+ and Oxford Horizons programmes help our sixth-formers prepare for university, while mentoring with Career Ready and the Civil Service supports our students to gain new skills from external providers. Our recent launch of The Spotlight, a newspaper run by students at SMSJ, has heralded a collaboration with a BBC Press Team. Again, this shows other opportunities for cross-curricular overlap, as students are directed to report on different departments’ extracurricular enrichment activities. The possibilities are endless, and limited only by our imagination.

To learn more about any of the initiatives mentioned in this blog post, and/or to share what’s working in your own department/school, please contact communications@nace.co.uk.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

collaboration

creativity

enrichment

free resources

independent learning

KS3

KS4

motivation

philosophy

writing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|