Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Zoe Enser,

15 November 2022

|

Zoe Enser, author of the new book Bringing Forth the Bard, shares eight key steps to help your students get to grips with (and enjoy!) the symbolic, allusive, musical, motif-packed language of Shakespeare.

The language of Shakespeare is perhaps one of the greatest barriers to most readers unfamiliar with its style, allusions and patterns. Shakespeare’s language can be something of a leveller as it doesn’t necessarily matter how proficient you are at reading generally; all students (and indeed many adults) will stumble across his words and need to deploy a different approach to reading than they are used to.

With so many finding the language problematic, there is a temptation to strip some of the complexity away; to focus instead on summaries or modern adaptations. There is, though, much to be gained by examining his words as they appear, much as you would when exploring a poem with your class.

Getting it can be really satisfying, and a key light-bulb moment for me at school was seeing how unpicking meaning could be looked at like a problem to be solved, much like solving equations in maths or finding the intricate pieces of a jigsaw. Most importantly perhaps is that his use of poetry, imagery and musicality frequently stays with us, and lines from Shakespeare that linger in our mind and our everyday language remain due to their crafting. We want to allow students to have that opportunity too.

Here are eight steps to bring Shakespeare’s language to life in your own classroom:

1. Begin by giving students an overview of the plot, characters and themes. Good quality performance, coupled with summary and questioning, will mean students arrive at language analysis ready to see how it relates to these bigger ideas. Audio readings of the plays can also be useful here to allow them to hear the language spoken and to model fluency.

2. Reassure students they won’t get it all immediately. Explain that the joy in studying Shakespeare’s language comes from the gradual understanding we gain and how it enriches our understanding, which is a process: one which even those familiar with his work will continue to go through. It is a process where we layer understanding, deepening each time we revisit it. If students have been used to exploring simpler texts this might be a challenge at first to consider this different approach, but model this for them, demonstrating how you can return to the same quote or extract again and again to delve deeper each time.

3. Look at short extracts and quotes from across a play or a range of texts to examine patterns and connections. Linger on individual words and then trace them as they are used elsewhere so students can notice where these links are and hypothesise as to why.

4. Use freely available searches to explore the frequency and location of key words and phrases. For example, a search on Open-Source Shakespeare reveals there are 41 direct references to ‘blood’ or ‘bloody’ in the play Macbeth, some of which are clustered within a few lines. This provides an opportunity to explore why this is the case and what Shakespeare was doing with these language choices. Equally, looking for references to the sun in Romeo and Juliet reveals 17 instances, and if then cross-referenced with light it brings forth a further 34 references, suggesting that there is a motif running through the text which demands further attention. Allowing students to explore this trail in their discussions and consider the prevalence of some words over others can reveal much about the themes Shakespeare was trying to convey too. For example, simply looking at the light and dark references in Romeo and Juliet enables students to see the binaries he has woven into the play to mirror the idea of conflict.

5. Discuss the imagery Shakespeare is trying to create with his language via pictures, selecting those which are most appropriate to convey his choices at different points. Thinking about how different audiences may respond to these is also a useful way to examine alternative interpretations of a single word, line or idea. This can also support learners with different needs as they have visual images to link to ideas, especially abstract ones, repeated throughout the text. This will provide them with something more concrete to link to the text and, as images are repeated throughout the narrative, can act as support for the working memory and enhance fluency of retrieval as they recognise the recurring images visually. This can be particularly useful for EAL students, supporting them to follow the plot and explore the patterns that emerge.

6. Teach aspects of metre (such as iambic and trochaic pentameter), ensuring students have lots of opportunities to hear the language spoken aloud so they can appreciate the musicality of the language and choice of form. Using methods such as walking the text, whereby students physically walk around the room whilst reading the text and responding to the punctuation, can be a powerful way to convey how a character feels at any given point. Lots of phrases, short clauses, or single syllable words can change the pace of the reading and we should model this and give students the opportunity to examine how this may then impact on performance. Long, languid sentences can create a different performance, and where the punctuation has finally landed in his work can reveal a lot about how a character or scene has been read. Try different ways of reading a single line to illustrate why we place emphasis on certain words and pauses at different points.

7. Read the text aloud together. As well as modelling reading for students, employing practices such as choral reading (where the class all read the text aloud together with you) or echo reading (where they repeat lines back) can be another way in which we remove the barriers the language can create. Students build confidence over time as the language becomes more familiar but also they do not feel so exposed as they are reading with the group, and not alone.

8. Let students play with and manipulate the language so they are familiar with it, and it doesn’t become a block to their interaction with the plays. Pre-teach the vocabulary, letting students consider words in isolation and explore quotes so that they don’t become overwhelmed at trying to interpret them. Even translating short phrases and passages can provide a useful coding activity which can support later analysis.

Zoe Enser was a classroom teacher for 20 years, during which time she was also a head of English and a senior leader with a responsibility for staff development and school improvement. This blog post is an excerpt from her latest book, Bringing Forth the Bard (Crown House Publishing). NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on this and all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website; for details log in to our member offers page.

Tags:

access

confidence

creativity

English

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

literacy

literature

oracy

pedagogy

reading

Shakespeare

vocabulary

writing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Chloe Bateman,

07 October 2022

|

Chloe Bateman is a Teacher of History at Maiden Erlegh School, a NACE Challenge Award-accredited school. Chloe has recently led the development of a whole-school oracy strategy. In this blog post, she shares some of the ways in which Maiden Erlegh has established and embedded a culture of oracy across the school to benefit all students, including the more able.

Oracy is ‘both everywhere and nowhere in a school’. At Maiden Erlegh, we realised that although plenty of classroom talk was taking place, opportunities for this could be ad hoc and students did not always recognise these as opportunities to develop oracy skills. At the same time, a significant number of students lacked the confidence to speak in front of larger groups and in more formal contexts, hindering their ability to engage with oracy-related elements of the taught curriculum and extracurricular activities. The national picture indicates that many schools experience similar challenges to developing student oracy and an oracy culture within the school.

Drawing on our experience, here are seven steps to establish a whole-school oracy culture:

1. Investigate your context to determine your priorities

Every school is different. Whilst the national trend shows a decline in oracy as a result of the Covid-19 lockdowns, every school will have different areas of strength and development in terms of the current oracy level of their students and their staff confidence in teaching to enhance oracy. Oracy too is itself a complex skill, made up not just of the verbal ability, but multiple components such as the physical and cognitive elements. To design a strategy which really works for your context, it is beneficial to gather student and staff voice to inform the precise nature of this. At Maiden Erlegh, we conducted quantitative and qualitative staff and student surveys, asking students to rate their level of confidence when communicating and why they may feel less confident in some areas than others. Staff were asked to share feedback on levels of student oracy and what support they would need to feel confident in developing an oracy culture in their own classrooms. From this data, we could easily identify clear priorities to be addressed through our strategy.

2. Secure buy-in from staff to secure buy-in from students

A strategy is only as effective as those who make it a reality on a day-to-day basis: the teaching staff. Our oracy work was launched via a training session to staff which centred on communicating the rationale for our new oracy focus. Here the student and staff voice surveys came into their own, enabling us to explain why we needed to develop oracy using the words of students and staff themselves and showing the overwhelming statistics. We also took time to share the wide-ranging holistic benefits of enhanced oracy for students, including for mental health, academic progress, and career opportunities. For maximum exposure, include students in the launch too and keep them as informed as you would do staff. We delivered assembles to all students sharing very similar messages to those shared during the staff launch, ensuring students were aware and engaged with our upcoming work.

3. Get staff and students on board with ‘quick wins’

It can be tempting to try to launch all strands of a strategy at once. However, this is unlikely to succeed in the long run as it risks overwhelming the very people you are attempting to get on board. Instead, generate enthusiasm and interest in oracy by sharing ‘quick wins’: low-preparation, high-impact activities to integrate more oracy opportunities into lessons. Staff and students loved our ‘no filler’ game in which students were challenged to answer questions or speak about a relevant topic without using filler words such as ‘erm’, ‘like’, and ‘basically’. As staff become more confident in creating their own oracy-based activities, encourage colleagues to share their own ‘quick wins’ via staff briefings and bulletins to build a culture of enthusiasm.

4. Give oracy an identity

Too often strategies and initiatives can be become lost in the organisational noise of a school and the day-to-day challenges and immediate priorities. Borrow from the world of marketing and promotions to create a clear identity for oracy by designing a logo and branding for your strategy using a simple graphic design website such as Canva. A catchy slogan can also help to build a ‘brand’ around the strategy and increase staff and student familiarity with the overall vision. At Maiden Erlegh School (MES), we use the slogan ‘MES Speaks Up!’ – a motto that has become synonymous with our vision for a culture of oracy across the school.

5. Establish and reinforce consistent high expectations for oracy

Most schools have shared and consistent high expectations for students’ literacy and numeracy, but how many have the same for oracy? Whilst many teachers will have high standards for communication in their classrooms, these will not have the same impact on students as if they are school-wide. At Maiden Erlegh, we established a set of ‘Guidelines for Great Oracy’, a clear list of five expectations including the use of formal vocabulary and projecting loudly and clearly. These expectations were launched to both staff and students and all classrooms now display a poster to promote them. The key to their success has been clearly communicating how easily these can be embedded into lessons, for example as success criteria for self- and peer-assessment during oracy-based activities such as paired or group discussions.

6. Create a shared understanding that oracy will enhance the existing curriculum

With so many competing demands on a classroom teacher’s time, it is easy to see why strategies and initiatives which feel like ‘add-ons’ can miss the mark and fail to become embedded in a school’s culture. Central to the success of our oracy strategy has been raising staff, student, and parent awareness that a focus on oracy will enhance our existing curriculum, rather than distract from it. From the very beginning, staff have been encouraged to return to existing lesson activities which cover existing content and adapt these with oracy in mind. In History, for example, an essay was preceded by a parliamentary debate to help students to construct convincing arguments, whilst in Maths students developed complex verbal explanations for the processes they were performing rather than simply completing calculations. Not only do such activities support oracy skills, but they demonstrate the inherent importance of oracy across the curriculum and allow departments to better meet their own curricular aims.

7. Keep the momentum going with high-profile events

As with any new strategy or initiative, we realised that after the initial enthusiasm there was a potential for staff and students to lose interest as the year wore on. To combat this, we developed high-profile events to return oracy to centre stage and engage students and staff alike. In May, we held MES Speaks Up! Oracy Month – a month of activities focused on celebrating oracy and its importance across all aspects of school life. In form time, students were challenged to discuss a topical ‘Question of the Day’ from our ‘Discussion Calendar’ to get them communicating from the moment they arrived in school. Every subject dedicated at least one lesson during the month to an activity designed to develop and celebrate oracy skills, including public speaking, debating, and presenting. Outside of lessons, students from each year group participated in a range of extracurricular parliamentary debates on issues relevant to their age group. All of these activities were widely promoted via our school social media to generate a buzz around oracy with our parents and guardians.

References

Interested in developing oracy within your own school?

• Join our free member meetup on this theme (18 October 2022)

• Join this year’s NACE R&D Hub with a focus on oracy for high achievement (first meeting 20 October 2022)

• Explore more content about oracy

Tags:

campaigns

confidence

curriculum

enrichment

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

oracy

pedagogy

personal development

questioning

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Howell's School, Llandaff,

20 June 2022

|

Sue Jenkins, Head of Years 10 and 11, and Hannah Wilcox, Deputy Head of Years 10 and 11, share five reasons they’ve found The Day an invaluable resource for tutor time activities.

Howell’s School, Llandaff, is an independent school in Cardiff which educates girls aged 3-18 and boys aged 16-18. It is part of the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST).

The Day publishes daily news articles and resources with the aim of help teachers inspire students to become critical thinkers and better citizens by engaging their natural curiosity in real-world problems. We first came across it as a library resource and recognised its potential for pastoral activities when the length of our tutor time sessions was extended to allow more discussion time and flexibility in their use.

Post-Covid, it has never been more important to promote peer collaboration, discussion and debate in schools. There is an ever-increasing need for students to select, question and apply their knowledge when researching; it has never been more important for students to have well-developed thinking and analytical skills. We find The Day invaluable in helping us to prompt students to discuss and understand current affairs, and to enable those who are already aware to extend and debate their understanding.

Here are five key pastoral reasons why we would recommend subscribing to The Day:

1. Timely, relevant topics throughout the year

You will always find a timely discussion topic on The Day website. The most recent topics feature prominently on the homepage, and a Weekly Features section allows you to narrow down the most relevant discussion topic for the session you are planning. Assembly themes, such as Ocean Day in June, are mapped across the academic year for ease of forward planning. We particularly enjoyed discussing the breakaway success of Emma Raducanu in the context of risk-taking, and have researched new developments in science, such as NASA’s James Webb telescope, in the week they have been launched.

2. Supporting resources to engage and challenge students

The need to involve and interest students, make sessions straightforward for busy form tutors, and cover tricky topics, combine to make it daunting to plan tutor time sessions – but resources linked to The Day’s articles make it manageable. Regular features such as The Daily Poster allow teachers to appeal to all abilities and learning styles with accessible and interesting infographics. These can also be printed and downloaded for displays, making life much easier for academic departments too. One of the best features we’ve found for languages is the ability to read and translate articles in target languages such as French and Spanish. Reading levels can be set on the website for literacy differentiation, and key words are defined for students to aid their understanding of each article.

3. Quick PSHE links for busy teachers

Asked to cover a class at the last minute? We’ve all been there! With The Day, you are sure to find a relevant subject story to discuss within seconds, and, best of all, be certain that the resources are appropriate for your students. With our Year 10 and 11 students, we have covered topics such as body image with the help of The Day by prompting discussion of Kate Winslet’s rejection of screen airbrushing. Using articles is particularly useful with potentially difficult or emotive issues where students may be more able to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of certain attitudes by looking at news events, detaching themselves from but also gaining insight about the personal situations they may be experiencing. The PSHE programme is vast; it is great to use The Day to plan tutor time sessions and gives us the opportunity to touch on a wide range of issues relatively easily.

4. Motivational themes brought to life through real stories

We have also found The Day’s articles useful for providing examples of motivational themes for our year groups. The Themes Calendar is particularly useful here; for example, tutor groups discussed the themes of resilience and diversity using the article on Preet Chandi’s trek to the South Pole. If you’re looking for assembly inspiration, The Day is a great starting point.

5. Develop oracy, thinking and research skills through meaningful debate

Each article has suggested tasks and discussion questions which we have found very useful for planning tutor time activities which develop students’ oracy, thinking and research skills. The Day promotes high-level debates about environmental, societal and political issues which students are keen to explore. One recent example is the discussion of privacy laws and press freedom prompted by the article about Rebel Wilson’s forced outing by an Australian newspaper. Activities can be easily adapted or combined to promote effective discussion. ‘Connections’ articles contain links to similar areas of study, helping teachers to plan and students to see the relevance of current affairs.

Find out more…

NACE is partnering with The Day on a free live webinar on Thursday 30 June, providing an opportunity to explore this resource, and its role within cognitively challenging learning, in more detail. You can sign up here, or catch up with the recording afterwards in our webinars library (member login required).

Plus: NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to The Day. For details of this and all current member offers, take a look at our member offers page (login required).

Tags:

critical thinking

enrichment

independent learning

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

libraries

motivation

oracy

personal development

questioning

research

resilience

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Tom Stewart,

01 April 2022

|

Tom Stewart, Head of History at Maiden Erlegh School, sets out tangible strategies that he and his department take when challenging more able students in history lessons.

History at secondary school level is a subject that, from my experience, is usually taught in mixed ability classes. Due to this, and to rightfully ensure the progress of those who struggle with literacy and require further support, lessons can tend to be pitched towards the middle with scaffolding and structure in place to help those struggling. The potential problem with this approach is that it risks neglecting the more able students and those who need to be challenged or stretched (or whichever phrase is used in your setting), to reach their potential. I hope this blog post will give you some ideas to take away to challenge the more able learners in your history lessons.

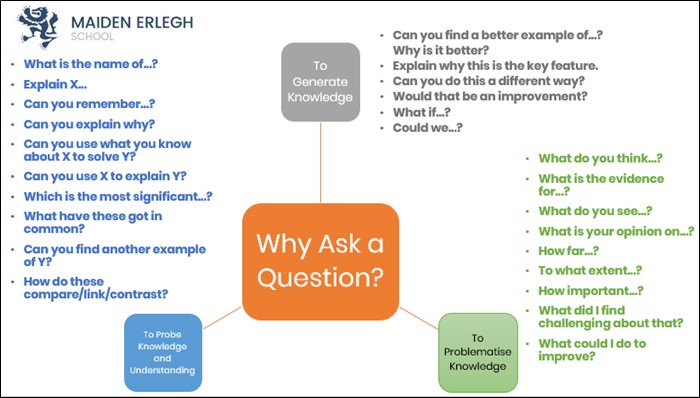

#1. Short-term: Questioning

A simple and easy way to challenge those more able students is through effective use of the questioning they face in a lesson. I imagine most teachers know about open and closed questions and how the latter can limit students to a one-word answer, whilst the former can require students to elaborate in more depth. Therefore, the answer the students give can often depend on how much thought has gone into the question asked.

It is important to consider why a teacher is asking a question and this can then be applied to challenging the more able students by asking a variety of questions for different reasons. In a recent CPD session at my school, delivered by two excellent Assistant Headteachers, Rob Buck and Ben Garner, this principle, with some examples, was shared with staff (Figure 1). It reminded myself and my department to think carefully about the questioning we carried out and to target those more able students, whether they be in Year 7, Year 10 or Year 13.

Figure 1

#2. Medium-term: Widen their perspectives

More able students are often characterised by a curious and inquisitive nature. To support this, it is important to not be overly selective with the history shared with students, but find opportunities to reveal more of the story. Students of all abilities enjoy learning knowledge that isn’t necessarily vital to the topic – knowledge that Bailey-Watson calls ‘hinterland’ knowledge – and we should be willing to share with students more of the big picture in order to widen their perspectives and improve their historical thinking.

Homework can be an outlet for this; the previously mentioned Bailey-Watson and Kennet launched their ‘meanwhile, elsewhere…’ project (Figure 2) with the explicit intention of ‘expanding historical horizons’. Used effectively, this is a strategy that challenges the more able students to make those links between what they know and what they are yet to know.

Figure 2

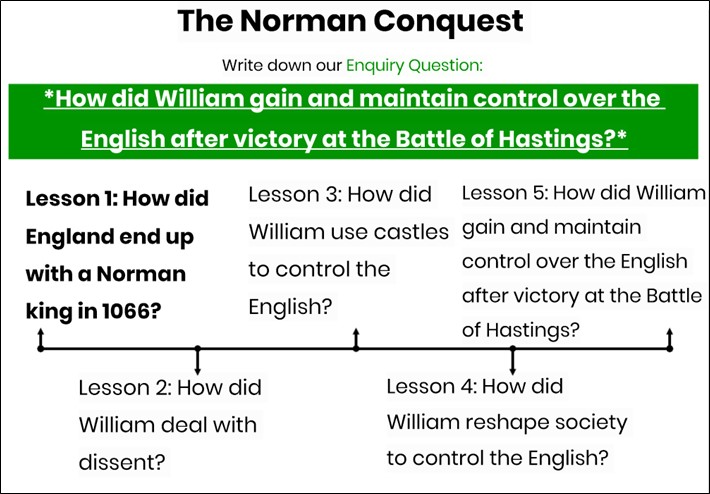

#3. Long-term: Enquiry-based topics

History lends itself to a wealth of interesting topics. This selection narrows at GCSE and A-Level as specifications force middle leaders to select one topic and not another. However, at Key Stage 3, there is normally more choice and also an opportunity to challenge more able students. We have found evolving already-established topics – or creating new ones where time allowed and necessity demanded – into enquiry-based ones supports more able students by forcing them to ‘think hard’.

Our topic on the Norman Conquest, an event described by Peter Rex as ‘the single most important event in English history’ avoids a simpler narrative of events and instead forces students, especially the more able, to consider how King William managed not only to gain control but maintain it after the Battle of Hastings (Figure 3). This topic was designed by my fantastic colleague, Chloe Bateman, and this approach provides all students with an overview of where the lesson and topic fits in and also encourages deep thinking about the answer to the enquiry question before it has even been covered.

Combined with sharing demanding texts with students in lessons and homework that relates directly to the enquiry question, whilst extending their knowledge and understanding even further, enquiry-based topics can prove very effective at challenging more able students in secondary history.

Figure 3

There are plenty of strategies out there and there are more that I use and could have shared with you, but here are three that you could look to introduce to your setting. The important point is to be mindful about the experience more able students get in our classrooms. Do they feel challenged? Would you in their shoes? If not, then be active in doing something about it.

References

- Bailey-Watson, W. and Kennett, R. (2019). '"Meanwhile, elsewhere…": Harnessing the power of community to expand students’ historical horizons’, Teaching History, 176.

- https://meanwhileelsewhereinhistory.wordpress.com/

- Paramore, J. (2017). Questioning to Stimulate Dialogue, in Paige R., Lambert, S. and Geeson, R. (eds), Building Skills for Effective Primary Teaching, London: Learning Matters.

- Rex, P. (2011). 1066: A New History of the Norman Conquest, Amberley Publishing.

Read more:

Tags:

enquiry

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elena Stevens,

28 March 2022

Updated: 24 March 2022

|

History lead and author Elena Stevens shares four approaches she’s found to be effective in diversifying the history curriculum – helping to enrich students’ knowledge, develop understanding and embed challenge.

Recent political and cultural events have highlighted the importance of presenting our students with the most diverse, representative history curriculum possible. The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the tearing down of Edward Colston’s statue the following month prompted discussion amongst teachers about the ways in which we might challenge received histories of empire, slavery and ‘race’; developments in the #MeToo movement – as well as instances of horrific violence towards women – have caused many to reflect on the problematic ways in which issues of gender are present within the curriculum. Diversification, decolonisation… these are important aims, the outcomes of which will enrich the learning experiences of all students, but how can we exploit the opportunities that they offer to challenge the most able?

At its heart, a more diverse, representative curriculum is much better placed to engage, inspire and include than one which is rooted in traditional topics and approaches. A 2018 report by the Royal Historical Society found that BAME student engagement was likely to be fostered through a broader and more ‘global’ approach to history teaching, whilst a 2014 study by Mohamud and Whitburn reported on the benefits of – in Mohamud and Whitburn’s case – shifting the focus to include the histories of Somali communities within their school. A history curriculum that reflects Black, Asian and ethnic minorities, as well as the experiences of women, the working classes and LGBT+ communities, is well-placed to capture the interest and imagination of young people in Britain today, addressing historical and cultural silences. There are other benefits, too: a more diverse offering can help not only to enrich students’ knowledge, but to develop their understanding of the historical discipline – thereby embedding a higher level of challenge within the history curriculum.

Below are four of the ways in which I have worked to diversify the history schemes of work that I have planned and taught at Key Stages 3, 4 and 5 – along with some of the benefits of adopting the approaches suggested.

1: Teach familiar topics through unfamiliar lenses

Traditionally, historical conflicts are taught through the prism of political or military history: students learn about the long-term, short-term and ‘trigger’ causes of the conflict; they examine key ‘turning points’; and they map the war’s impact on international power dynamics. However, using a social history approach to deliver a scheme of work about, for example, the English Civil War, complicates students’ understanding of the ‘domains’ of history, shifting the focus so that students come to appreciate the numerous ways in which conflict impacts on the lives of ‘ordinary’ people. The story of Elizabeth Alkin – the Civil War-era nurse and Parliamentary-supporting spy – can help to do this, exposing the shortfalls of traditional disciplinary approaches.

2: Complicate and collapse traditional notions of ‘power’

Exam specifications (and school curriculum plans) are peppered with influential monarchs, politicians and revolutionaries, but we need to help students engage with different kinds of ‘power’ – and, beyond this, to understand the value of exploring narratives about the supposedly powerless. There were, of course, plenty of powerful individuals at the Tudor court, but the stories of people like Amy Dudley – neglected wife of Robert Dudley, one of Elizabeth I’s ‘favourites’ – help pupils gain new insight into the period. Asking students to ‘imaginatively reconstruct’ these individuals’ lives had they not been subsumed by the wills of others is a productive exercise. Counterfactual history requires students to engage their creativity; it also helps them conceive of history in a less deterministic way, focusing less on what did happen, and more on what real people in the past hoped, feared and dreamed might happen (which is much more interesting).

3: Make room for heroes, anti-heroes and those in between

It is important to give the disenfranchised a voice, lingering on moments of potential genius or insight that were overlooked during the individuals’ own lifetimes. However, a balanced curriculum should also feature the stories of the less straightforwardly ‘heroic’. Nazi propagandist Gertrud Scholtz-Klink had some rather warped values, but her story is worth telling because it illuminates aspects of life in Nazi Germany that can sometimes be overlooked: Scholtz-Klink was enthralled by Hitler’s regime, and she was one of many ‘ordinary’ people who propagated Nazi ideals. Similarly, Mir Mast challenges traditional conceptions of the gallant imperial soldiers who fought on behalf of the Allies in the First World War, but his desertion to the German side can help to deepen students’ understanding of the global war and its far-reaching ramifications.

4: Underline the value of cultural history

Historians of gender, sexuality and culture have impacted significantly on academic history in recent years, and it is important that we reflect these developments in our curricula, broadening students’ history diet as much as possible. Framing enquiries around cultural history gives students new insight into the real, lived experiences of people in the past, as well as spotlighting events or time periods that might formerly have been overlooked. A focus, for example, on popular entertainment (through a study of the theatre, the music hall or the circus) helps students construct vivid ‘pictures’ of the past, as they develop their understanding of ‘ordinary’ people’s experiences, tastes and everyday concerns.

There is, I think, real potential in adopting a more diversified approach to curriculum planning as a vehicle for embedding challenge and stretching the most able students. When asking students to apply their new understanding of diverse histories, activities centred upon the second-order concept of significance help students to articulate the contributions (or potential contributions) that these individuals made. It can also be interesting to probe students further, posing more challenging, disciplinary-focused questions like ‘How can social/cultural history enrich our understanding of the past?’ and ‘What can stories of the powerless teach us about __?’. In this way, students are encouraged to view history as an active discipline, one which is constantly reinvigorated by new and exciting approaches to studying the past.

About the author

Elena Stevens is a secondary school teacher and the history lead in her department. Having completed her PhD in the same year that she qualified as a teacher, Elena loves drawing upon her doctoral research and continued love for the subject to shape new schemes of work and inspire students’ own passions for the past. Her new book 40 Ways to Diversify the History Curriculum: A practical handbook (Crown House Publishing) will be published in June 2022.

NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website; for details of this and all NACE member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

References

Further reading

- Counsell, C. (2021). ‘History’, in Cuthbert, A.S. and Standish, A., eds., What should schools teach? (London: UCL Press), pp. 154-173.

- Dennis, N. (2021). ‘The stories we tell ourselves: History teaching, powerful knowledge and the importance of context’, in Chapman, A., Knowing history in schools: Powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge (London: UCL Press), pp. 216-233.

- Lockyer, B. and Tazzymant, T. (2016). ‘“Victims of history”: Challenging students’ perceptions of women in history.’ Teaching History, 165: 8-15.

More from the NACE blog

Tags:

critical thinking

curriculum

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By NACE team,

10 February 2022

|

Hodder Education’s Review magazines provide subject-specific expertise aimed at GCSE and A-level students, featuring the latest research, thought-provoking articles, exam-style questions and discussion points to deepen learners’ subject knowledge and develop independent learning skills.

Earlier this academic year, we partnered with Hodder on a live webinar for NACE members, followed by an opportunity to undertake a free trial subscription to the Review magazines, and then reconvening for an online focus group to share experiences, ideas and feedback.

Below are 15 ways NACE members suggested this resource could be used:

- Wider reading – encouraging learners to read more widely in their subjects, developing deeper and broader subject knowledge

- Flipped learning – tasking students with reading an article (or articles) on a topic ahead of a lesson, so they are prepared to discuss during class time (members noted that this approach benefits from practising reading comprehension during lesson time first)

- Developing cultural capital – exposure to content, contexts, vocabulary, and text formats which learners might not otherwise encounter

- Independent research and project work – to support independent research and projects such as EPQs, for example by using the digital archives to search on a particular theme

- Developing literacy and vocabulary – exposure to subject-specific and advanced vocabulary; this was highlighted by some schools as a particular concern post-pandemic

- Shared text during lessons – used to support lessons on a particular topic, and/or to develop comprehension skills

- Developing exam skills – using the magazines’ links to specific exam skills/modules, and practice exam questions at the end of articles

- Examples of academic/exam skills in practice – providing examples of how a text or topic could be approached and analysed, and ways of structuring an essay/response

- Library resource – signposted to students and teachers by school librarian to ensure a diverse, challenging reading menu is available to all

- Linking learning to real-world contexts – providing examples of how curriculum content is being applied in current contexts around the world, helping to bring learning to life

- Broadening career horizons – examples of different careers in each subject area, giving learners exposure to a range of potential future pathways

- Extracurricular provision – used as a resource to support subject-specific clubs, or general research/debate clubs

- Developing critical thinking and oracy skills – to support strategies such as the Harkness method, as part of a wider focus on developing critical thinking and oracy skills

- Exposure to academic research – preparing students for further education and career opportunities

- Fresh perspectives on curriculum content – new angles and insights on well-established modules and topics – for teachers, as well as students!

Find out more:

Discount offer for NACE members

NACE members can benefit from a 25% discount on Hodder's digital and print resources, including the Review magazines (excluding student £15 subscriptions). To access this, and our full range of member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

Does your school use the Review magazines or a similar resource? To share your experience and ideas, contact communications@nace.co.uk

Tags:

aspirations

enrichment

independent learning

KS4

KS5

literacy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Chris Yapp,

26 August 2020

|

This blog post is based on an article originally published on LinkedIn on 16 August 2020 – click here to read in full.

The fallout from A-level and GCSE results will be uncomfortable for government and upsetting and challenging for teachers and students alike. Arguments over whether this year’s results are robust and fair miss one key issue.

Put simply: "Has the exam system in England ever been robust and fair for individual pupils?"

For those of us who did well in exams and whose children also did well, it is too easy to be confident. Accepting that our success and others’ failure is a systemic problem, not a result of competence and capability, is not easy.

Let me be clear: I do not have confidence in the exam system in England as a measure either of success or capability.

[…] Try this as a thought experiment. Imagine that I gave an exam paper submission to 100 examiners. Let me assume that it "objectively" is a C grade.

Would all 100 examiners give it a C? If not, what is the spread? Is the spread the same for English literature, physics and geography, as just three examples? If you cannot provide clear evidenced answers to these questions, how can you be confident that the system is objective?

If we look at the examiners, the same challenge appears. Are all examiners equally consistent in their marking, or do some tend to mark up or down? Where is the evidence, reviewed and published to demonstrate robustness?

We also know that the month you are born still has an effect on GCSE grades. What is robust about that?

[…] I have known children who have missed out on grades after divorce, separation and death of parents, siblings and pets. I cannot objectively give a measure of the impact, but then neither can the exam system. I would add that I suspect a classmate of mine missed out because of hayfever. Children with health issues such as leukaemia and asthma whose schooling is disrupted have had their grades affected every year, not just this one.

So, the high stakes exam system is, for me, a winner-takes-all loaded gun embedding inequality and privilege in the outcomes.

Can we do better? Well, if we want to use exams, then each paper needs to be marked by say five independent assessors. If they all agree on a "B" then that is a measure of confidence. This is often a model used for assessing loans, grants and investments in businesses. It does not guarantee success of course, but what it does is reduce reliance on potentially biased individuals. If I was an examiner and woke up today in a foul mood, would I mark a paper the same today as yesterday? I would not bet on it.

The really interesting cases in my experience are where you get 2As, a C and 2Ds, for instance. In my experience, I've seen it more often in "creative subjects", but some non-traditional thinkers in subjects like mathematics (a highly creative discipline, by the way) often don't fit the narrow models of assessment of our exam system. The problem with this example of bringing people together to try get a consensus on a "B" is that it eliminates the value that comes from the diverse views and the richness of the different perceptions.

So, for me, for a system to be robust it has to have more than one measure to allow the individual, parents, universities, FE and employers access to a richer view of an individual. If someone got an ABBCD in English that is as interesting as someone who got straight Bs.

[…] There are already models that command respect in grading skill levels. Parents are quite happy if a child is doing grade 6 piano and grade 2 flute at the same time. They are quite happy for a child to sit when ready and have the chance to resit. Yet in the school setting the pressure is there for a child to be at level 8 say for all subjects. That puts unnecessary pressure on pupils, teachers and schools.

Imagine how society would react if you could only take the driving test once at 17 and barriers were raised to stop you retaking it.

[…] This year’s bizarre algorithmic system is not robust, but then we have never had a robust system as far as I am concerned. Let's open our eyes and build something that we should have more confidence in. Carpe diem.

Join the discussion: share your views in the comments below (member login required).

Tags:

assessment

disadvantage

KS4

KS5

lockdown

policy

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By The Bromfords School & Sixth Form College,

03 July 2020

|

Amy Clark, Assistant Headteacher for Quality of Education, explains how The Bromfords School and Sixth Form College has used Microsoft Teams to support both students and staff – delivering remote learning, pastoral support and peer-led CPD.

Being thrust into the world of remote learning has galvanised us to dig deep as a profession and do what we do best: find ways to make learning enjoyable – even in the toughest of times. At The Bromfords School, a small group of us had already been trialling the use of Microsoft Teams with our sixth form pupils to enhance the provision they were receiving, with the focus on enabling students to participate in a learning-rich environment without having to be in the classroom. Students loved having access to a digital learning space, outside of school, that they could use to have academic debates on key topics, share links to wider reading or resources and generally support each other in a collaborative way.

We also saw Teams as a way for staff to share best practice CPD. We all know what happens when you attend an amazing INSET day or twilight session; you eventually find time to do planning and create some wonderful resources that you share with colleagues, but they get lost amongst the mass of emails, meaning the brilliant work done often gets lost. The plan was to use Microsoft Teams to provide a specific space for professional dialogue about teaching and learning, where teachers could share resources, upskill each other and continue to develop as professionals.

Then along came COVID-19 and thrust our plans forward…

Using Teams for academic, pastoral and peer support

Even though the timeline for rolling out Microsoft Teams across the school was sped up, our staff certainly rose to the challenge. Whilst Teams isn’t the only software we have used to communicate remote learning to students, it is quickly becoming a space that students use for both academic and pastoral purposes.

Tutor group channels were set up on Teams for every year group, where tutors have been able to ‘check in’ each week with pupils. This has ensured that students’ academic needs are met, that students have access to advice should they need it, but most importantly, tutors could keep track of students’ mental wellbeing. Open lines of communication meant that if a child was struggling, we could support them. Students didn’t know how to work remotely, how to organise their time or how to be self-motivated; our use of Teams has provided them with methods for easy communication with an adult they are familiar with on a daily basis.

We hope that by having the lines of communication open to students and having a compulsory check-in each week, the bridge between students working in isolation at home and returning back into the building is eased and that that we are able to lower anxiety for our students.

Our Teams CPD channel has supported staff not only in developing their IT skills to enable the best possible provision for students, but also in accessing a range of ideas they might not have come across before. Our channel has ‘How to…’ videos on topics including the use of narrated PowerPoints, quizzes or forms on Teams, how to use ‘assignments’ within Teams and mark these using a rubric to give feedback on the work completed, to name just a few. Staff have also shared information on how to create drop-down and tick-boxes in Microsoft Word, where to go to get icons for dual coding, methods for increasing student engagement and other concepts that will improve remote learning.

Even staff members who are self-proclaimed ‘technophobes’ have been able to develop their IT skills to ensure the digital learning process for our pupils is as strong as it can be. The channel has enabled everyone to feel like we are all in this process together, all learning together – and nothing is as daunting when you have others by your side.

Five core principles for effective remote learning

As a school, we were keen to ensure we were catering to the needs of all our pupils during this time, with our more able students being a key focus. We wanted to ensure the provision offered to this group remained high quality so they were able to continue to be challenged academically – avoiding the dreaded generic worksheet, a one-size-fits-all approach. We also found that many of our more able were struggling with managing workload, which developed increased levels of anxiety.

A group of leaders and I developed what we felt were the five core principles of remote learning and delivered this to staff through CPD meetings, to ensure our more able students were academically and emotionally supported.

We felt that remote learning should be:

- Concrete: it should have a clear purpose and learning intent that fits with the wider curriculum. There should also be clear timings for tasks so that students do not spend excessive amounts of time on projects.

- Inclusive: consider how you stretch your most able students by providing links to wider reading, podcasts, challenge tasks or breadth of choice such as presentation methods.

- Considerate: taking into consideration students’ learning environments and access to materials they could need. Also planning tactically so that students do not become overwhelmed with the sheer amount of work expected of them.

- Reflective: students should have feedback at key points and self-assessment opportunities through sharing clearly defined success criteria.

- Engaging: staff should incorporate a range of learning activities and software to avoid students becoming demotivated. Also focusing on mechanisms for praise so that students know their hard work is being recognised.

The concepts here are not new. But when staff are also dealing with the pressures and anxiety a COVID-19 teaching world presents, it is a timely reminder that the core principles of teaching must remain so that students can continue to succeed. The five core principles listed above all aim not only to enrich the remote learning a student receives, but also take into consideration students’ mental wellbeing too.

When we return to school, I hope the lessons learnt from using technology during this time do not get lost. Many members of staff have told me how much they have enjoyed using Microsoft Teams to support learning and how they will continue to use it moving forward, particularly to aid collaborative work with peers and to support home learning. Our eyes have been opened to the potential of this technology in supporting and enriching the curriculum for more able students though many of the methods listed above. It has certainly provided both staff and students with a very different learning experience, with the potential to continue to enrich learning beyond the classroom for students and increase enjoyment in developing pedagogy for staff.

Read more:

Tags:

apps

collaboration

CPD

KS5

lockdown

pedagogy

remote learning

technology

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Alex Pryce, Oxplore,

30 November 2018

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

Looking for ideas to challenge your more able learners in the humanities? In this blog post, Dr Alex Pryce selects four “Big Questions” from the University of Oxford’s Oxplore project that will spark debate, relate the humanities to the modern world, and encourage independence of mind…

Oxplore is an innovative digital outreach portal from the University of Oxford. As the “Home of Big Questions”, it aims to engage 11- to 18-year-olds with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom. Tackling complex ideas across a wide range of subjects and drawing on the latest research undertaken at Oxford, Oxplore aims to raise aspirations and stimulate intellectual curiosity.

Our “Big Questions” reflect the kind of thinking students undertake at universities like Oxford. Each question is accompanied by supporting resources – including videos; quiz questions; possible answers, explanations and areas for investigation; and suggestions from Oxford faculty members and current undergraduates.

The following four questions touch on subjects as diverse as history, philosophy, literature, linguistics and psychology. They are daring, provocative and rooted in current issues. Teachers can use them to engage able learners as the focus for a mini research project, a topic for classroom debate, or the springboard for students to think up Big Questions of their own.

Over 6,000 languages are spoken worldwide… what’s the point? Imagining a world without linguistic difference will encourage learners to think more globally, while examining the benefits of multilingualism will start conversations about culture, nationality and identity. Investigate multilingualism’s benefits and drawbacks, both historically and with reference to today’s world. For additional stimulation, check out the recording of Oxplore’s live event on this Biq Question.

Perfect for: interdisciplinary language teaching.

This question challenges students to think more deeply about why they hold their beliefs, who shapes their behaviour and choices, and how this colours their view of the world. It also creates room for able learners to have nuanced discussions about complex topical issues such as political beliefs, sexuality and ethnic identity, but with reference to public figures they care about – so they get the chance to focus the discussion.

Perfect for: demonstrating the present-day relevance of humanities subjects.

A classic foray into historiographical thinking which can be used to debate questions such as… How have the internet, photoshopping and so-called “fake news” affected our grip on the truth? To what extent does the adage that history is written by the winners stand up in the age of social media? How have racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination shaped the history we consume? For more on this question, check out this recorded Oxplore live stream event.

Perfect for: humanising historians and fostering critical thinking.

Explore philosophy, history and the history of art by encouraging learners to think about humanity’s long association with religion and spirituality. Does religion encourage moral behaviour? What about religious extremism? Examine the implications of religious devotion in fields such as power, community and education, and encourage the sensitive exploration of alternative views.

Perfect for: conducting a balanced debate on controversial issues.

Dr Alex Pryce is Oxplore’s Widening Access and Participation Coordinator (Communications and Engagement), leading on marketing and dissemination activities including stakeholder engagement and social media. She has worked in research communications, public engagement and PR for several years through roles in higher education (HE) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). She holds a DPhil in English from the University of Oxford and is a part-time HE tutor.

Tags:

access

aspirations

free resources

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

languages

oracy

philosophy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Alex Pryce, Oxplore,

23 April 2018

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

Looking for ideas to challenge your more able learners in maths? In this blog post, Alex Pryce selects four maths-focused “Big Questions” from Oxplore, an initiative developed by the University of Oxford.

Oxplore is an innovative digital outreach portal from the University of Oxford. As the “Home of Big Questions”, it aims to engage 11- to 18-year-olds with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom. Big Questions tackle complex ideas across a wide range of subjects, drawing on the latest research undertaken at Oxford.

In this blog post, I’ve selected four Big Questions which could offer super-curricular enrichment in different areas of mathematical enquiry. Teachers could ask students to use the questions as the starting point for a mini research project, or challenge them to create their own Big Questions to make practical use of mathematical skills. The questions could also be used to introduce more able mathematicians to fields they could study at university.

Delve into the digits with an exploration of two very different careers. Discover the statistics behind the professions, and debate how difficult these job choices are. We all know that nurses do a fantastic job, but what about footballers who devote their time to charity work? Who should earn more? Get involved in debating labour markets, minimum wage, and the supply and demand process.

Perfect for: budding economists and statisticians.

What does truth really mean? Can we separate what we believe to be true from scientific fact? Discuss what philosophers and religious figures have to say on the matter, and ponder which came first: mathematics or humans? Did we give meaning to mathematics? Has maths always existed? Learn about strategies to check the validity of statistics, “truth” as defined in legal terms, and the importance of treating data with care.

Perfect for: mathematicians with an interest in philosophy or law.

Take a tour through the history of money, debate how much cash you really need to be happy, and consider the Buddhist perspective on this provocative Big Question. Discover the science behind why shopping makes us feel good, and explore where our human needs fit within Maslow’s famous hierarchy.

Perfect for: those interested in economics, sociology and numbers.

How can we avoid bad luck? Where does luck even come from, and are we in control of it? Where does probability come into luck? Delve into the mathematics behind chance and the law of averages and risk, taking a journey through the maths behind Monopoly on the way!

Perfect for: those interested in probability, decision-making and of course, board-game fans!

Alex Pryce is Oxplore’s Widening Access and Participation Coordinator (Communications and Engagement), leading on marketing and dissemination activities including stakeholder engagement and social media. She has worked in research communications, public engagement and PR for several years through roles in higher education (HE) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). She holds a DPhil in English from the University of Oxford and is a part-time HE tutor.

Tags:

access

aspirations

economics

ethics

higher education

KS3

KS4

KS5

maths

oracy

philosophy

questioning

STEM

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|