Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Oliver Barnes,

04 December 2024

|

Ollie Barnes is lead teacher of history and politics at Toot Hill School in Nottingham, one of the first schools to attain NACE Challenge Ambassador status. Here he shares key ingredients in the successful addition of a module on Hong Kong to the school’s history curriculum. You can read more in this article published in the Historical Association’s Teaching History journal.

When the National Security Law came into effect in Hong Kong, it had a profound and unexpected impact 6000 miles away, in Nottinghamshire’s schools. Important historical changes were in process and pupils needed to understand them. As a history department in a school with a growing cohort of Hong Kongers, it became essential to us that students came to appreciate the intimate historical links between Hong Kong and Britain and this history was largely hidden, or at least almost entirely absent, in the history curriculum.

But exploring Hong Kong gave us an opportunity to tell our students a different story, explore complex concepts and challenge them in new ways. Here I will outline the opportunities that Hong Kong can offer as part of a broad and diverse curriculum.

Image source: Unsplash

1. Tell a different story

In our school in Nottinghamshire, the student population is changing. Since 2020, the British National Overseas Visa has allowed hundreds of families the chance to start a new life in the UK. Migration from Hong Kong has rapidly increased. Our school now has a large Cantonese-speaking cohort, approximately 15% of the school population. The challenge this presented us with was how to create a curriculum which is reflective of our students.

Hong Kong offered us a chance to explore a new narrative of the British Empire. In textbooks, Hong Kong barely gets a mention, aside from throwaway statements like ‘Hong Kong prospered under British rule until 1997’. We wanted to challenge our students to look deeper.

We designed a learning cycle which explored the story of Hong Kong, from the Opium Wars in 1839 to the National Security Law in 2020. This challenged our students to consider their preconceptions about Hong Kong, Britain’s impact and migration.

2. Use everyday objects

To bring the story to life, we focused on everyday objects, which are commonly used by our students and could help to tell the story.

First, we considered a cup of tea. We asked why a drink might lead to war? We had already explored the Boston Tea Party, as well as British India, so students already knew part of this story, but a fresh perspective led to rich discussions about war, capitalism, intoxicants and the illegal opium trade.

Our second object was a book, specifically Mao’s Little Red Book. We used it to explore the impact of communism on China, showing how Hong Kong was able to develop separately, with a unique culture and identity.

Lastly, an umbrella. We asked: how might this get you into trouble with the police? Students came up with a range of uses that may get them arrested, before we revealed that possessing one in Hong Kong today could be seen as a criminal act. This allowed us to explore the protest movement post-handover.

At each stage of our enquiry, objects were used to drive the story, ensuring all students felt connected to the people we discussed.

Umbrella Revolution Harcourt Road View 2014 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

3. Keep it complex

In order to challenge our students, we kept it complex. They were asked to draw connections and similarities between Hong Kong and other former British colonies. We also wanted them to encounter capitalism and communism, growth and inequality. Hong Kong gave us a chance to do this in a new and fresh way.

Part of this complexity was to challenge students’ preconceptions of communism, and their assumptions about China. By exploring the Kowloon walled city, which was demolished in 1994, students could discuss the problems caused by inequality in a globalised capitalist city.

Image source: Unsplash

What next?

Our Year 9 students responded overwhelmingly positively. The student survey we conducted showed that they enjoyed learning the story and it helped them understand complex concepts.

Hong Kong offers curricula opportunities beyond the history classroom. In English, students can explore the voices of a silenced population, forced to flee or face extradition. In geography, Hong Kong offers a chance to explore urbanisation, the built environment and global trade.

Additional reading and resources

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

enquiry

history

KS3

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Tom Stewart,

01 April 2022

|

Tom Stewart, Head of History at Maiden Erlegh School, sets out tangible strategies that he and his department take when challenging more able students in history lessons.

History at secondary school level is a subject that, from my experience, is usually taught in mixed ability classes. Due to this, and to rightfully ensure the progress of those who struggle with literacy and require further support, lessons can tend to be pitched towards the middle with scaffolding and structure in place to help those struggling. The potential problem with this approach is that it risks neglecting the more able students and those who need to be challenged or stretched (or whichever phrase is used in your setting), to reach their potential. I hope this blog post will give you some ideas to take away to challenge the more able learners in your history lessons.

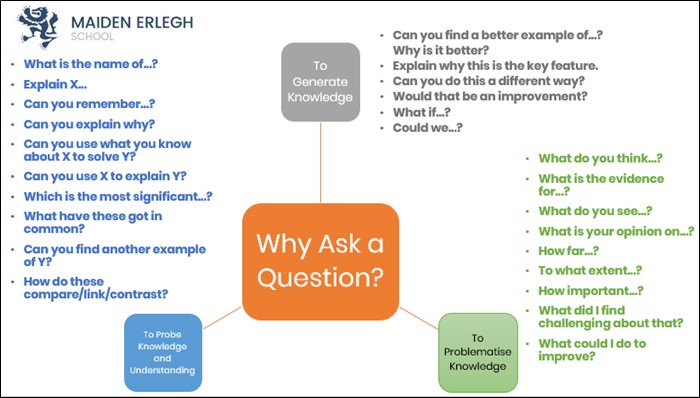

#1. Short-term: Questioning

A simple and easy way to challenge those more able students is through effective use of the questioning they face in a lesson. I imagine most teachers know about open and closed questions and how the latter can limit students to a one-word answer, whilst the former can require students to elaborate in more depth. Therefore, the answer the students give can often depend on how much thought has gone into the question asked.

It is important to consider why a teacher is asking a question and this can then be applied to challenging the more able students by asking a variety of questions for different reasons. In a recent CPD session at my school, delivered by two excellent Assistant Headteachers, Rob Buck and Ben Garner, this principle, with some examples, was shared with staff (Figure 1). It reminded myself and my department to think carefully about the questioning we carried out and to target those more able students, whether they be in Year 7, Year 10 or Year 13.

Figure 1

#2. Medium-term: Widen their perspectives

More able students are often characterised by a curious and inquisitive nature. To support this, it is important to not be overly selective with the history shared with students, but find opportunities to reveal more of the story. Students of all abilities enjoy learning knowledge that isn’t necessarily vital to the topic – knowledge that Bailey-Watson calls ‘hinterland’ knowledge – and we should be willing to share with students more of the big picture in order to widen their perspectives and improve their historical thinking.

Homework can be an outlet for this; the previously mentioned Bailey-Watson and Kennet launched their ‘meanwhile, elsewhere…’ project (Figure 2) with the explicit intention of ‘expanding historical horizons’. Used effectively, this is a strategy that challenges the more able students to make those links between what they know and what they are yet to know.

Figure 2

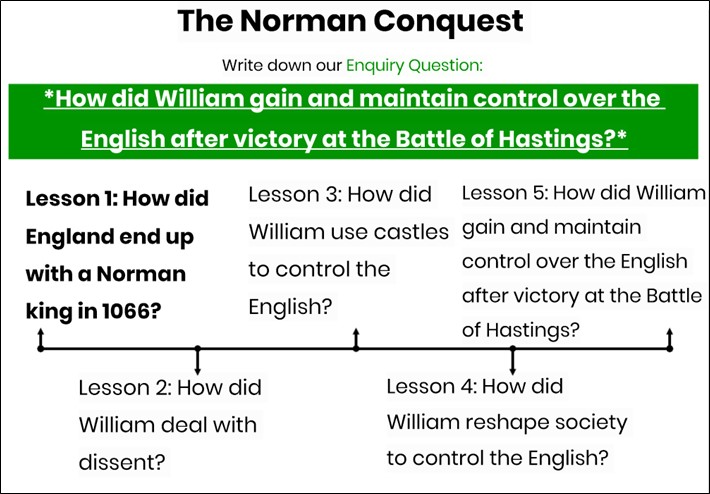

#3. Long-term: Enquiry-based topics

History lends itself to a wealth of interesting topics. This selection narrows at GCSE and A-Level as specifications force middle leaders to select one topic and not another. However, at Key Stage 3, there is normally more choice and also an opportunity to challenge more able students. We have found evolving already-established topics – or creating new ones where time allowed and necessity demanded – into enquiry-based ones supports more able students by forcing them to ‘think hard’.

Our topic on the Norman Conquest, an event described by Peter Rex as ‘the single most important event in English history’ avoids a simpler narrative of events and instead forces students, especially the more able, to consider how King William managed not only to gain control but maintain it after the Battle of Hastings (Figure 3). This topic was designed by my fantastic colleague, Chloe Bateman, and this approach provides all students with an overview of where the lesson and topic fits in and also encourages deep thinking about the answer to the enquiry question before it has even been covered.

Combined with sharing demanding texts with students in lessons and homework that relates directly to the enquiry question, whilst extending their knowledge and understanding even further, enquiry-based topics can prove very effective at challenging more able students in secondary history.

Figure 3

There are plenty of strategies out there and there are more that I use and could have shared with you, but here are three that you could look to introduce to your setting. The important point is to be mindful about the experience more able students get in our classrooms. Do they feel challenged? Would you in their shoes? If not, then be active in doing something about it.

References

- Bailey-Watson, W. and Kennett, R. (2019). '"Meanwhile, elsewhere…": Harnessing the power of community to expand students’ historical horizons’, Teaching History, 176.

- https://meanwhileelsewhereinhistory.wordpress.com/

- Paramore, J. (2017). Questioning to Stimulate Dialogue, in Paige R., Lambert, S. and Geeson, R. (eds), Building Skills for Effective Primary Teaching, London: Learning Matters.

- Rex, P. (2011). 1066: A New History of the Norman Conquest, Amberley Publishing.

Read more:

Tags:

enquiry

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Daisy Morley,

28 March 2022

Updated: 22 March 2022

|

Daisy Morley, primary teacher and history lead at Calcot Schools, outlines her approach to identifying and challenging more able learners in history – building historical knowledge, understanding and enquiry skills.

As a teacher it currently seems to me that a lot of attention is given to the children who need to meet age-related expectations. While these pupils’ needs are important and their needs must be met, this focus can mean that greater depth and ‘more able’ pupils are often forgotten. It is essential that more able learners are not neglected and are given ample opportunities to showcase their knowledge and shine.

History is one subject where, through careful consideration and planning, more able learners can thrive. Within this blog post, I will examine how to identify and challenge more able learners in history, in the context of primary teaching. These thoughts derive from personal experiences and from extensive research on the relevant literature and recent Ofsted reports. I will focus on ‘historical knowledge’, ‘historical understanding’ and ‘historical enquiry’ in order to suggest how we can think about challenging more able learners in history.

More able in history or just literacy?

Often, children whose strength lies in history will find that they are confident in literacy. Although strong literacy skills will greatly benefit their ability to share, form and communicate their ideas and findings, this does not necessarily mean that they are or will be more able historians. Interestingly, I think that the personal interests of children play a pivotal part in whether they have excelled in history beyond their age-related expectations. This is true from children as young as Year 1, to pupils nearing the end of their primary education. As educators, particularly if you are a subject leader, it is essential that time is taken to identify those children with a personal interest in history, and to provide them with opportunities to showcase their knowledge.

The building blocks: historical knowledge

First and foremost, the subject of history is rooted in knowledge; it is a knowledge-based subject (Runeckles, 2018: 10). While it is essential that pupils’ analytical skills are developed, this cannot be done without first ensuring that all pupils have a secure grounding in historical knowledge. This is also made clear in recent literature from Ofsted inspectors. Tim Jenner, HMI, Ofsted’s subject lead for history, has stated that when teaching history there must be an emphasis placed on content and knowledge (Jenner, 2021). In the most recent Ofsted reports, the term ‘knowledge’ has been divided into knowledge of ‘substantive concepts’, which relates to broader concepts, such as empire, monarch and economy, and ‘chronological knowledge’, which refers to the broader concepts within history, such as the key features of Anglo-Saxon England (Jenner, 2021).

The National Curriculum does expect pupils to “understand the methods of historical enquiry, including how evidence is used rigorously to make historical claims, and discern how and why contrasting arguments and interpretations of the past have been constructed” (DFE, 2013). The enquiry and analytical skills required to thrive in history are essential. However, these skills cannot be developed without first imparting the key historical knowledge to children.

Facts are the building blocks of history.

To emphasise this point, let us look at an example. Imagine a teacher wants to include a module on Boudicca in their history curriculum. Boudicca is listed in the National Curriculum for History under a non-statuary example, and has crucial ties with the statuary module on the Roman Empire and its impact on Britain. For the pupils to understand Boudicca’s historical significance, they would first need to have a secure grasp of the key features of the Roman Empire. Following this, they would then need to be taught the key components of Britain during this time. This knowledge would be essential before embarking on a specialised study of Boudicca. If the teacher then wished to hone and develop pupils’ analytical and enquiry skills, they could include a lesson on the conflicting sources that are available regarding Boudicca. To understand the primary written sources, however, they would first need to have a secure understanding of the historical knowledge of Boudicca, the Roman Empire, and the political landscape of Britain during this time.

Building historical knowledge takes time, as it requires a build-up of knowledge. As a result, educators may not see this accumulation of knowledge until a significant period of learning time has passed. Nevertheless, for children to develop their enquiry skills, historical knowledge is essential.

Developing historical understanding through open-ended questions

To see progression within a pupil’s historical understanding, historical knowledge, understanding and enquiry are best taught alongside one another. Historical knowledge and understanding are inextricably linked, and it would be difficult to separate these concepts within every lesson. Nevertheless, if a child is demonstrating the potential to achieve beyond the age-related expectations in history, their historical understanding could be one way to identify this – and thus to extend and challenge their learning. More able learners often process the key historical knowledge more quickly than their peers, which in turn means that they often quickly grasp the role of criteria in formulating and articulating an historical explanation or argument. Furthermore, more able learners are frequently able to draw generalisations and conclusions from a range of sources of evidence. One way to identify this could be ensuring that teachers ask open-ended questions, as the answers that children arrive at depend largely on questions asked.

I try to implement these open-ended questions in lessons, particularly across Key Stage 2. One approach which has worked particularly well came to light in a Year 3 lesson on “What did the diet of a typical Stone Age person encompass in prehistoric Britain?” This lesson relied on enquiry-based learning, which, although sometimes more difficult to deliver, lent itself well to inputting open-ended questions and highlighted the investigative nature of history. The children were given ‘organic evidence’ (pretend human waste), which pivoted around unpicking evidence and how historians use different types of evidence to find out about the past.

From this lesson, after unpicking our evidence, all of the children were able to deduce that prehistoric people ate nuts, seeds and berries. Pupils with a more advanced understanding were able to conclude that prehistoric inhabitants had to find food for themselves and that this is one of the reasons people from that time are called ‘hunter-gatherers’, because they had to hunt and gather their food.

For the children who had already come to the conclusions about hunter-gatherers, I asked more open-ended questions, which required them to draw their own conclusions, using the evidence that had been assessed, including “What about the meat?”, “Why haven’t we found meat in the organic evidence?” Some of these children were able to utilise their knowledge from previous lessons on Stone Age Britain and concluded that there were certain dangers in finding meat. They explained that people had to kill the animal and prepare it themselves, which was dangerous. One child even went on to say that meat also rots and that may have been why there was no surviving meat within the evidence. Although these open-ended questions help to stretch the more able learners, it does require teachers to direct the more challenging questions to the correct pupils, which relies on teachers knowing which of the pupils are excelling in history.

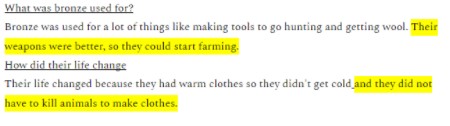

Making links: developing historical enquiry skills

I often find that historical enquiry skills are the hardest to master. From teaching this within lessons, it seems the key component to identifying the more able learners in history is to identify whether the pupils can link history together. Can they use their knowledge to comment on how the lives of people from the past have changed over time? Can they identify trends and commonalities between contemporary cultures? Do they notice how key changes transformed the lives and the culture of a particular civilisation? Perhaps most essentially, can the more able children use their historical knowledge and understanding to draw conclusions on events, people and places from the past? This relies on a pupil being able to problem-solve and reason with evidence, and apply this knowledge in order to evaluate the evidence in question.

Below is an example of a child’s work. The lesson was titled “What was bronze used for?”

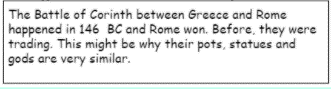

I have chosen this example because this pupil was able to link their knowledge together, to form their own conclusions, which were based on key factual knowledge. For example, this child independently came to the conclusion that because their weapons were better, their quality of life improved. Amazingly, this pupil also commented on the fact that people from the Bronze Age in Britain no longer had to kill animals to make clothes, which meant that their lives really changed. Below is another example of a pupil drawing from their accumulated knowledge, in order to compare and contrast civilisations:

This is another example of a greater-depth learner in action. They had knowledge of Greece and Rome, and a battle that took place. Already, it is clear that they have an understanding of the cross-over and interaction between these two civilisations. Not only this, but they also know that trade took place between the two civilisations. Finally, they have commented on how this trade is clear from primary evidence. This pupil has not only demonstrated that they hold a secure knowledge of the Battle of Corinth, but they have also highlighted their ability to use evidence to draw their own historically valid conclusions.

To support and enable pupils to draw conclusions and analogies from historical sources, it is vital for the teacher to model how to do this (Runeckles, 2018:52). In mathematics, for example, you would not expect children to solve a worded problem on multiplication, which required reasoning, without first teaching them the basic skills of multiplication. How often do you model being a historian to your class?

For example, imagine you are teaching your class about the Spartans. The written sources on Sparta derive largely from sources written at a much later date, and not composed by Spartans. One could take an example from a Roman scholar (Aristotle or Plato) on the Spartan education system, the Agoge, and explain that these individuals were Roman and lived two hundred years after Classical Greece had ended. One could then ask, “How might that affect their account?” This sort of task could be implemented within a range of topics and encourages a dialogue between teachers and pupils. If these enquiry-based examples and questions are built into lessons, across modules, pupils are provided with opportunities to enhance their ability to analyse evidence and draw conclusions from a vast amount of evidence.

And finally…

Although I have separated the teaching of history into historical knowledge, historical understanding and historical enquiry, ultimately each of these elements is best taught concurrently. It is possible to include each of these aspects within one lesson, particularly as they are inextricably linked.

Perhaps most importantly, it is crucial to ensure that teachers are ambitious, not only with curriculum coverage, but also with regards to their expectations of pupils. Regardless of whether pupils have demonstrated that they are more able, children of all abilities thrive on high expectations and on knowing their teacher believes they can and will accomplish great things. So get your young historians thinking!

References

Read more:

Tags:

critical thinking

enquiry

history

humanities

KS2

literacy

problem-solving

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By School Library Association,

28 March 2022

Updated: 24 March 2022

|

Dawn Woods, Member Development Librarian, and Hannah Groves, Marketing and Communications Officer, School Library Association

If there is one subject a librarian can help teaching colleagues with, it is definitely history. From providing engaging reads for primary pupils to assisting with A-Level research for the curriculum or supporting EPQ projects, the school library is home to a wealth of resources.

For primary pupils, a history topic may start with a novel set during the period to be studied. Historical novels take the reader back to explore how life was during that time and can help explain the historical context. Library staff will be able to suggest a range of suitable titles to help with this, whatever the period.

GCSE-level students will be expected to read around the subject to complete their homework, and so the librarian will introduce pupils to the library catalogue to help them locate the resources available to them. As well as hardcopy books, e-books and online journals will be catalogued under subject headings, so students searching for their history topic are alerted to what the library holds on that subject, whatever the media format. By the time students are on their A-Level course, they will be using these to research curriculum topics and, in the case of the EPQ, on topics of their own choice.

Here are three key ways your school library can support the teaching of history:

1. Use the library catalogue as a research tool

School library staff will teach students that the library catalogue is a gateway to resources in many formats, all grouped under keyword headings, preparing our young people for independent learning. Once students go on to university they will require this very skill, so they will be well prepared for further study.

2. Share curated content and resources

Some libraries may present students with resources as a reading list, some may have Padlets or other online presentations. The value of these online presentations is that they take pupils directly to the sites librarians have already earmarked as useful for the topic. As Padlets contain all types of content – whether that be text, documents, images, videos or weblinks – librarians can bring together a wide range of material for a particular class or year group and subject. For example, this Padlet on ‘history for all ages’ contains reading lists as well as weblinks to safe sites for primary and secondary students. This means that young people are not wasting time finding unsuitable resources, which may lead them to the wrong conclusions.

3. Subscribe to online journals

If your school offers the EPQ, where older secondary students choose their own topic, students must research this themselves. The library is integral to this and subscriptions to online journals can help enormously here. The topic students are researching may be very specific and not generally covered in published books which, by the very nature of going through the publishing process, take a long time to be available. Research written up in journals is current and academically verified, so with a subscription to a resource such as JSTOR students have access to “peer-reviewed scholarly journals, respected literary journals, academic monographs, research reports, and primary sources from libraries’ special collections and archives.” [Another example is Hodder’s Review magazines, which NACE members recently trialled.]

The school library and library staff are your friends when teaching history to learners of any age, so do make sure you use their resources to save time for all.

About the School Library Association

The School Library Association (SLA) is a charity that works towards all schools in the UK having their own (or shared) staffed library. Our vision is for all school staff and children to have access to a wide and varied range of resources and have the support of an expert guide in reading, research, media and information literacy. To find out more about what the SLA could do for you, visit our website, follow us on Twitter, or get in touch.

Read more:

Tags:

enrichment

history

historyfree resources

independent learning

literacy

reading

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elena Stevens,

28 March 2022

Updated: 24 March 2022

|

History lead and author Elena Stevens shares four approaches she’s found to be effective in diversifying the history curriculum – helping to enrich students’ knowledge, develop understanding and embed challenge.

Recent political and cultural events have highlighted the importance of presenting our students with the most diverse, representative history curriculum possible. The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the tearing down of Edward Colston’s statue the following month prompted discussion amongst teachers about the ways in which we might challenge received histories of empire, slavery and ‘race’; developments in the #MeToo movement – as well as instances of horrific violence towards women – have caused many to reflect on the problematic ways in which issues of gender are present within the curriculum. Diversification, decolonisation… these are important aims, the outcomes of which will enrich the learning experiences of all students, but how can we exploit the opportunities that they offer to challenge the most able?

At its heart, a more diverse, representative curriculum is much better placed to engage, inspire and include than one which is rooted in traditional topics and approaches. A 2018 report by the Royal Historical Society found that BAME student engagement was likely to be fostered through a broader and more ‘global’ approach to history teaching, whilst a 2014 study by Mohamud and Whitburn reported on the benefits of – in Mohamud and Whitburn’s case – shifting the focus to include the histories of Somali communities within their school. A history curriculum that reflects Black, Asian and ethnic minorities, as well as the experiences of women, the working classes and LGBT+ communities, is well-placed to capture the interest and imagination of young people in Britain today, addressing historical and cultural silences. There are other benefits, too: a more diverse offering can help not only to enrich students’ knowledge, but to develop their understanding of the historical discipline – thereby embedding a higher level of challenge within the history curriculum.

Below are four of the ways in which I have worked to diversify the history schemes of work that I have planned and taught at Key Stages 3, 4 and 5 – along with some of the benefits of adopting the approaches suggested.

1: Teach familiar topics through unfamiliar lenses

Traditionally, historical conflicts are taught through the prism of political or military history: students learn about the long-term, short-term and ‘trigger’ causes of the conflict; they examine key ‘turning points’; and they map the war’s impact on international power dynamics. However, using a social history approach to deliver a scheme of work about, for example, the English Civil War, complicates students’ understanding of the ‘domains’ of history, shifting the focus so that students come to appreciate the numerous ways in which conflict impacts on the lives of ‘ordinary’ people. The story of Elizabeth Alkin – the Civil War-era nurse and Parliamentary-supporting spy – can help to do this, exposing the shortfalls of traditional disciplinary approaches.

2: Complicate and collapse traditional notions of ‘power’

Exam specifications (and school curriculum plans) are peppered with influential monarchs, politicians and revolutionaries, but we need to help students engage with different kinds of ‘power’ – and, beyond this, to understand the value of exploring narratives about the supposedly powerless. There were, of course, plenty of powerful individuals at the Tudor court, but the stories of people like Amy Dudley – neglected wife of Robert Dudley, one of Elizabeth I’s ‘favourites’ – help pupils gain new insight into the period. Asking students to ‘imaginatively reconstruct’ these individuals’ lives had they not been subsumed by the wills of others is a productive exercise. Counterfactual history requires students to engage their creativity; it also helps them conceive of history in a less deterministic way, focusing less on what did happen, and more on what real people in the past hoped, feared and dreamed might happen (which is much more interesting).

3: Make room for heroes, anti-heroes and those in between

It is important to give the disenfranchised a voice, lingering on moments of potential genius or insight that were overlooked during the individuals’ own lifetimes. However, a balanced curriculum should also feature the stories of the less straightforwardly ‘heroic’. Nazi propagandist Gertrud Scholtz-Klink had some rather warped values, but her story is worth telling because it illuminates aspects of life in Nazi Germany that can sometimes be overlooked: Scholtz-Klink was enthralled by Hitler’s regime, and she was one of many ‘ordinary’ people who propagated Nazi ideals. Similarly, Mir Mast challenges traditional conceptions of the gallant imperial soldiers who fought on behalf of the Allies in the First World War, but his desertion to the German side can help to deepen students’ understanding of the global war and its far-reaching ramifications.

4: Underline the value of cultural history

Historians of gender, sexuality and culture have impacted significantly on academic history in recent years, and it is important that we reflect these developments in our curricula, broadening students’ history diet as much as possible. Framing enquiries around cultural history gives students new insight into the real, lived experiences of people in the past, as well as spotlighting events or time periods that might formerly have been overlooked. A focus, for example, on popular entertainment (through a study of the theatre, the music hall or the circus) helps students construct vivid ‘pictures’ of the past, as they develop their understanding of ‘ordinary’ people’s experiences, tastes and everyday concerns.

There is, I think, real potential in adopting a more diversified approach to curriculum planning as a vehicle for embedding challenge and stretching the most able students. When asking students to apply their new understanding of diverse histories, activities centred upon the second-order concept of significance help students to articulate the contributions (or potential contributions) that these individuals made. It can also be interesting to probe students further, posing more challenging, disciplinary-focused questions like ‘How can social/cultural history enrich our understanding of the past?’ and ‘What can stories of the powerless teach us about __?’. In this way, students are encouraged to view history as an active discipline, one which is constantly reinvigorated by new and exciting approaches to studying the past.

About the author

Elena Stevens is a secondary school teacher and the history lead in her department. Having completed her PhD in the same year that she qualified as a teacher, Elena loves drawing upon her doctoral research and continued love for the subject to shape new schemes of work and inspire students’ own passions for the past. Her new book 40 Ways to Diversify the History Curriculum: A practical handbook (Crown House Publishing) will be published in June 2022.

NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website; for details of this and all NACE member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

References

Further reading

- Counsell, C. (2021). ‘History’, in Cuthbert, A.S. and Standish, A., eds., What should schools teach? (London: UCL Press), pp. 154-173.

- Dennis, N. (2021). ‘The stories we tell ourselves: History teaching, powerful knowledge and the importance of context’, in Chapman, A., Knowing history in schools: Powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge (London: UCL Press), pp. 216-233.

- Lockyer, B. and Tazzymant, T. (2016). ‘“Victims of history”: Challenging students’ perceptions of women in history.’ Teaching History, 165: 8-15.

More from the NACE blog

Tags:

critical thinking

curriculum

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Alex Pryce, Oxplore,

30 November 2018

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

Looking for ideas to challenge your more able learners in the humanities? In this blog post, Dr Alex Pryce selects four “Big Questions” from the University of Oxford’s Oxplore project that will spark debate, relate the humanities to the modern world, and encourage independence of mind…

Oxplore is an innovative digital outreach portal from the University of Oxford. As the “Home of Big Questions”, it aims to engage 11- to 18-year-olds with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom. Tackling complex ideas across a wide range of subjects and drawing on the latest research undertaken at Oxford, Oxplore aims to raise aspirations and stimulate intellectual curiosity.

Our “Big Questions” reflect the kind of thinking students undertake at universities like Oxford. Each question is accompanied by supporting resources – including videos; quiz questions; possible answers, explanations and areas for investigation; and suggestions from Oxford faculty members and current undergraduates.

The following four questions touch on subjects as diverse as history, philosophy, literature, linguistics and psychology. They are daring, provocative and rooted in current issues. Teachers can use them to engage able learners as the focus for a mini research project, a topic for classroom debate, or the springboard for students to think up Big Questions of their own.

Over 6,000 languages are spoken worldwide… what’s the point? Imagining a world without linguistic difference will encourage learners to think more globally, while examining the benefits of multilingualism will start conversations about culture, nationality and identity. Investigate multilingualism’s benefits and drawbacks, both historically and with reference to today’s world. For additional stimulation, check out the recording of Oxplore’s live event on this Biq Question.

Perfect for: interdisciplinary language teaching.

This question challenges students to think more deeply about why they hold their beliefs, who shapes their behaviour and choices, and how this colours their view of the world. It also creates room for able learners to have nuanced discussions about complex topical issues such as political beliefs, sexuality and ethnic identity, but with reference to public figures they care about – so they get the chance to focus the discussion.

Perfect for: demonstrating the present-day relevance of humanities subjects.

A classic foray into historiographical thinking which can be used to debate questions such as… How have the internet, photoshopping and so-called “fake news” affected our grip on the truth? To what extent does the adage that history is written by the winners stand up in the age of social media? How have racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination shaped the history we consume? For more on this question, check out this recorded Oxplore live stream event.

Perfect for: humanising historians and fostering critical thinking.

Explore philosophy, history and the history of art by encouraging learners to think about humanity’s long association with religion and spirituality. Does religion encourage moral behaviour? What about religious extremism? Examine the implications of religious devotion in fields such as power, community and education, and encourage the sensitive exploration of alternative views.

Perfect for: conducting a balanced debate on controversial issues.

Dr Alex Pryce is Oxplore’s Widening Access and Participation Coordinator (Communications and Engagement), leading on marketing and dissemination activities including stakeholder engagement and social media. She has worked in research communications, public engagement and PR for several years through roles in higher education (HE) and the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC). She holds a DPhil in English from the University of Oxford and is a part-time HE tutor.

Tags:

access

aspirations

free resources

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

languages

oracy

philosophy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ben Weddell, National Maritime Museum,

03 January 2018

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

The National Maritime Museum recently hosted a NACE member meetup exploring approaches to working in depth for the more able. Following on from the event, the museum’s Ben Weddell explains how an enquiry-based approach to history can be used to inspire and challenge learners of all ages and abilities.

Recently the National Maritime Museum (NMM) learning team were lucky enough to host a NACE member meetup. Following a presentation on SOLO Taxonomy and a “speed sharing” session, we had the opportunity to share the museum’s approach to teaching historical enquiry and how this can translate to the classroom, based on my experiences at the NMM and as a secondary history teacher.

History as an investigative process

A fascinating aspect of learning about the past is the realisation that we have to discover it. Far from a list of dates and occurrences to be memorised and regurgitated, history can – should – be an investigative subject of discovery.

This is a far more interesting and engaging approach, and one which provides opportunities to personalise and differentiate, by giving learners agency for the routes they take in uncovering the past.

Indeed, for history to have any meaning as a subject I would argue that it has to be investigative. It is through the skills which constitute a historical methodology that “history” comes to make sense as a coherent single subject.

Defining a historical method

If challenged about the scientific method, most teachers would be able to outline the “hypothesis, experimentation, new hypothesis” model. Is it possible to repeat that for history? If there is a scientific method that learners can grasp, surely there has to be an equivalent for history.

Historical enquiry is the skill that fills this gap. This starts from the premise that we don’t know what happened in the past and have to discover this for ourselves – a great learning opportunity as this is where learners themselves begin. Rather than treating learners as passive vessels to be topped up with historical information, this approach challenges them to uncover the past themselves.

Furthermore, there is an expectation in the national curriculum that enquiry will be taught:

“Pupils are expected to understand the methods of historical enquiry, including how evidence is used rigorously to make historical claims, and discern how and why contrasting arguments and interpretations of the past have been constructed.”

This process builds from KS1 to KS2 and 3, developing skills in dealing with isolated blocks of evidence and then establishing links between these, culminating in the ability to assess, ask questions of, and reflect on a large bank of potentially contradictory evidence and come to sound conclusions.

Harnessing the power of objects

One way to engage learners in this journey is to incorporate object-based enquiry. History teaching often focuses around the spoken and written word, resulting in a teacher-led approach. Using objects, especially in a multisensory capacity, can add interesting new dimensions to learning:

Increased motivation and curiosity

- Accessibility, through the ability for learners to raise their own questions

- Multisensory approaches providing different access points for a range of learners

- “Realness” – aiding understanding of abstract ideas through a focus on tangible objects

- Cross-curricular opportunities for literacy, incorporation of other forms of evidence and other subject areas

It is possible to build enquiry opportunities using a huge range of objects, so developing a specific object bank is useful but not essential. Whether making use of printed resources or actual physical objects, the process of conducting an enquiry is what brings the object to life.

Let learners find their own challenge

Larger enquiries offer extensive opportunities for teachers. The key is to provide a limited amount of initial evidence and then allow learners to formulate their own responses. This creates effective differentiation and provides unique opportunities for learners to create their own working level, including the more able.

Furthermore, a creative introduction to the initial information – say roleplaying an archaeological discovery or a new finding in a document or database – provides motivation for learners to set themselves a challenging question.

It is then possible to expand investigations with the introduction of new evidence. There is flexibility in the range and scope of evidence you introduce, which will be determined by learners’ needs and level. For instance, a limited suitcase of objects could be investigated by KS1 learners, whereas by KS3 a teacher could overload learners with objects, so they have to differentiate between useful evidence and red herrings or irrelevant information.

In practice this could take the form of:

- One-off mysteries (KS1/KS2): a collection of objects to consider and a simple guided outcome, for instance “Whose suitcase might this be?”

- Developed enquiries (KS2/KS3): building on initial discoveries to develop an entire scheme of work, for instance “Why was this object found in the Arctic?”, leading into a wider investigation of John Franklin’s doomed final voyage to the Arctic, linking more widely to Arctic exploration.

- Self-led enquiries (KS3): initial collection of evidence and a problem, leading to a project including opportunities for learners to define their own questions and route, selecting appropriate evidence from a wide range and engaging with controversies.

All of these models follow the same process – starting with initial evidence, developing a hypothesis, testing with additional evidence, then repeating with a new hypothesis and so on. The cyclical nature of this process is marked by increasing degrees of certainty in learners’ findings as they increase the depth and range of the evidence they have based their ideas upon.

Enquiry as part of a wider pedagogy

Making enquiry a central part of learning has a number of benefits. It revolves around approaching topics with a focus on teaching skills that can then be used to access content, as opposed to a discrete delivery of content and skills. In turn, this means that history begins to make coherent sense, challenging some learners’ misconception that it is “just stuff that has happened”.

The skills acquired will also be more easily transferable and encourage a cross-curricular approach. Significantly, these skills are highly applicable to a wider world in which the ability to assess and sift incoming information is becoming ever more crucial.

Historical enquiry fits well with other pedagogies, such as SOLO Taxonomy or other progressive models such as Bloom’s. As the enquiry progresses, individual learners move through different stages of thinking skills, with initial stages of identification and definition, progressing to description of evidence, classification and analysis, through to evaluation and hypothesising around a wide range of evidence.

This approach forms the basis for historical enquiry sessions at the National Maritime Museum. These sessions include KS1 investigations into where breakfast comes from, full-day secondary study sessions incorporating original archive materials, and expert research sessions for post-16 students. You can find out more about these sessions on our website or through our guide to school programmes, which can be found here.

Useful links:

- National Maritime Museum for schools – including information about school visits, CPD opportunities, downloadable resources and more.

- Royal Museums Greenwich collections – searchable database of the Royal Musuems Greenwich collections, ranging from maps and charts to a taxidermy penguin! Includes images and information which can easily be adapted as resources for teaching and learning.

- Spartacus Educational – free-to-use site hosting historical resources and materials, useful for creating banks of evidence to build an enquiry.

- Thinking History – website of Ian Dawson, one of the founders of the Schools History Project, with a huge array of fantastic enquiry-based sessions available for free.

Ben is a learning producer at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, where he specialises in historical enquiry programmes for learners of all ages. He previously worked as a history teacher in secondary schools and a sixth form college, with a particular interest in opportunities to build historical enquiry into the curriculum. To find out more about Ben’s work and how your school could get involved, contact NACE and we will put you in touch.

Tags:

enquiry

free resources

history

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|