Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Rachel Macfarlane,

09 January 2025

|

Do academically strong pupils at your school who are on the Pupil Premium register progress as quickly and attain as highly as academically strong pupils who are not?

Do these students sometimes grasp new concepts quickly and securely in the classroom and show flair and promise in lessons, only to perform less well in exams than their more advantaged peers?

If so, what can be done to close the attainment gap?

In this series of three blog posts, Rachel Macfarlane, Lead Adviser for Underserved Learners at HFL Education, explores the reasons for the attainment gap and offers practical strategies to help close it – focusing in Part 1 on diagnosing the challenges and barriers, and in Part 2 on eliminating economic exclusion. This third instalment explores the importance of a sense of belonging and status.

Our yearning to belong is one of the most fundamental feelings we experience as humans. In psychologist Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the need to experience a sense of connection and belonging sits immediately above the need for basic necessities – food, water, warmth and personal safety.

When we experience belonging, we feel calm and safe. We become more empathetic and our mood improves. In short, as Owen Eastwood explains, belonging is “a necessary condition for human performance” (Belonging, 2021:26).

Learners from less economically advantaged backgrounds than their peers often feel that they don’t fit in and have a low sense of self-worth, regardless of their academic strength. Painfully aware of what they lack compared to others, they can disappear into the shadows, consciously or subconsciously making themselves invisible. They may not volunteer to read or answer questions in class. Or audition for a part in the school play or choir. Or sign up for leadership opportunities.

They may lack the respect, rank and position that is afforded by fitting comfortably into the ‘in group’: identifying with and operating within the dominant culture, possessing the latest designer gear, phone and other material goods, being at the centre of social media groups and activity and connecting effortlessly, through lived experiences and lifestyle, with peers who hold social power and are seen as leaders and role models.

Pupils who are academically strong but who lack status are likely to be fragile and nervous learners, finding it harder to work in teams, to trust others and to accept feedback. Their energy and focus can be sapped by the trauma of navigating social situations, they are prone to feel the weight of external scrutiny and judgement, and all of that will detract from their ability to perform at their best.

The good news is that, as educators, we have amazing powers to convey a sense of belonging and status.

Ten top tips to build learners’ sense of belonging and status

The following simple behaviours convey the message that the educator cares about, is invested in, notices and respects the learner; that they have belief in their potential and want to give their discretionary effort to them.

- Welcome them to the class, ensuring that you make eye contact, address them by name and give them a smile – establishing your positive relationship and helping them feel noticed, valued and safe in the learning environment.

- Go out of your way to find opportunities to give them responsibilities or assign a role to them, making it clear to them the skills and/or knowledge they possess that make(s) them perfect for the job.

- Reserve a place for them at clubs and ensure they are well inducted into enrichment opportunities.

- Arrange groupings for activities to ensure they have supportive peers to work with.

- Invite them to contribute to discussions, to read and to give their opinions. Don’t allow confident learners to dominate the discussion (learners with high status talk more!) and don’t ask for volunteers to read (students with low status are unlikely to volunteer).

- Show respect for their opinions and defer to them for advice. e.g. “So, I’m wondering what might be the best way to go about this. Martha, what do you think?” “That’s a good point, Nitin. I hadn’t thought of that. Thank you!”

- Make a point of telling them you think they should put themselves forward for opportunities (e.g. to go to a football trial, audition for the show, apply to be a prefect) and provide support (e.g. with writing an application or practising a speech).

- Connect them with a champion or mentor (adult or older peer) from a similar background who has achieved success to build their self-belief.

- Secure high-status work experience placements or internships for them.

- Invite inspiring role models with similar lived experience into school or build the stories of such role models into schemes of learning and assemblies.

Finally, it is worth remembering that classism (judging a person negatively based on factors such as their home, income, occupation, speech, dialect or accent, lifestyle, dress sense, leisure activities or name) is rife in many schools, as it is in society. In schools where economically disadvantaged learners thrive and achieve impressive outcomes, classism is treated as seriously as the ‘official’ protected characteristics. In these schools, the taught curriculum and staff unconscious bias, EDI (equality, diversity and inclusion) and language training address classism directly and leaders take impactful action to eliminate any manifestations of it.

More from this series:

Plus: this year's NACE Conference will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

CEIAG

confidence

disadvantage

enrichment

higher education

mentoring

mindset

motivation

resilience

transition

underachievement

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Rachel Macfarlane,

09 January 2025

|

Do academically strong pupils at your school who are on the Pupil Premium register progress as quickly and attain as highly as academically strong pupils who are not?

Do these students sometimes grasp new concepts quickly and securely in the classroom and show flair and promise in lessons, only to perform less well in exams than their more advantaged peers?

If so, what can be done to close the attainment gap?

In this series of three blog posts, Rachel Macfarlane, Lead Adviser for Underserved Learners at HFL Education, explores the reasons for the attainment gap and offers practical strategies for supporting economically disadvantaged learners who have the potential to access high grades and assessment outcomes to excel in tests and exams.

It is estimated that almost one in three children in Britain are living in relative poverty – 700,000 more than in 2010. A significant number of these pupils will be learners who show academic flair and the capacity to acquire knowledge and skills with ease, but whose progress and outcomes are impacted by the real costs of the curriculum and the school day.

In Part 1, I reflected that learners from economically disadvantaged backgrounds often lack the abundance of social and cultural capital that their more advantaged peers have amassed, which can disadvantage them in tests and exams. Most schools work hard to build the social and cultural capital of their underserved learners, through the provision of trips and visits, speakers and visitors, extracurricular clubs and other enriching experiences. Yet such activities often have associated (sometimes hidden) costs that exclude certain students.

At HFL Education, we have been carrying out Eliminating Economic Exclusion (EEE) reviews for the past three years, examining the impact of the cost of the school day. These involve surveying pupils, parents, staff and governors, meeting with Pupil Premium (PP) eligible learners, examining key data and training staff. Reviews conducted in well over 100 primary and secondary schools have revealed that learners eligible for PP are less likely to attend extracurricular clubs and to go on curriculum visits and residentials, resulting in them missing vital learning that can impact on their exam and test performance.

Often PP eligible learners:

- Will not inform their parents of activities that have a cost, regardless of whether the school might subsidise or fund the activity;

- Will feign disinterest in opportunities that they know are unaffordable to their families;

- Will not take up fully funded enrichment opportunities due to other associated costs such as travel to a funded summer school, or the costs of camping equipment and/or specific clothing required for field work or an outward-bound activity;

- Will not stay on after school for activities because they are hungry and lack the resources to purchase a snack.

Ten top tips to help eliminate economic exclusion:

- Ensure that all staff have undertaken training to heighten their awareness of poverty and the financial pressures faced by many families in relation to the costs of the school day.

- Track sign-ups and attendance by PP eligibility at enrichment activities. Take action where you see underrepresentation.

- Contact parents directly to stress how valuable it would be for their child to attend and to explain the financial support that can be provided.

- Set up payment plans and give maximum notice to allow families to spread the costs.

- Book activity centres out of season when costs are lower.

- Use public transport rather than private coaches or plan visits to sites that are within a walkable distance.

- Ban visits to shops and food outlets to eradicate the need for spending money on trips.

- Set up virtual gallery tours and film screenings of plays and arrange for visiting theatre companies, bands and artists to come to school rather than taking the students to concert halls, theatres and galleries.

- Build up a stock of loanable equipment (wellies, coats, tents, waterproof clothing, musical instruments, sporting equipment, craft materials etc.)

- Provide free snacks for learners staying for after-school clubs.

Finally, various studies have found that pupils from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are also underrepresented in cohorts studying certain subjects, where there are significant costs of materials/tuition/coaching, notably music, PE, art and drama at KS4 and KS5.

The Education Policy Institute’s 2020 report showed that economically disadvantaged learners are 38% less likely to study music at GCSE than their more affluent classmates and that at the end of KS4 they are 20 months behind their peers. This is perhaps not surprising given the estimated cost of instrumental tuition (£8,000-15,000) involved in reaching grade 8 standard on an instrument (required to access a top A-level grade).

So pupils who are high performers in certain curriculum subjects at age 14 may not opt to continue with their studies at GCSE and beyond, unless the school is able to ensure access to all the resources they need to thrive and attain at top levels.

Three key questions to consider:

- Do you track which learners opt for each course at KS4 and KS5, ask questions and act accordingly where you see underrepresentation of PP eligible learners?

- Do you prioritise PP eligible learners for 1:1 options and advice at KS3>4, KS4>5 and KS5>higher education, to ensure that they are aiming high, pursuing their passions and aware of all the financial support available (e.g. use of bursary funding, reassurance around logistics of university student loans)?

- Do you determine, and strive to meet, the precise resource needs of each PP eligible learner?

More from this series:

Plus: this year's NACE Conference will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

disadvantage

enrichment

parents and carers

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Rachel Macfarlane,

09 January 2025

|

Do academically strong pupils at your school who are on the Pupil Premium register progress as quickly and attain as highly as academically strong pupils who are not?

Do these students sometimes grasp new concepts quickly and securely in the classroom and show flair and promise in lessons, only to perform less well in exams than their more advantaged peers?

If so, what can be done to close the attainment gap?

In this series of three blog posts, Rachel Macfarlane, Lead Adviser for Underserved Learners at HFL Education, explores the reasons for the attainment gap and offers practical strategies for supporting economically disadvantaged learners who have the potential to access high grades and assessment outcomes to excel in tests and exams.

This first post examines the challenges and barriers often faced by economically disadvantage learners and offers advice about precise diagnosis and smart identification of needs. Part 2 explores strategies for eliminating economic exclusion, while Part 3 looks at ways to build a sense of belonging and status for these learners to enhance their performance.

The problem with exams

The first point to make is that high stakes terminal tests and exams tend not to favour learners from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. These learners often lack the abundance of social and cultural capital that their more advantaged peers have amassed. This can result in a failure to recognise and connect with the cultural references frequently found in SATs and exam questions.

Students on the Pupil Premium (PP) register have a lower average attendance rate than those from more affluent backgrounds. Those living in multiple occupancy and/or crowded housing are more exposed to germs and viruses, and families in rented or local authority housing move accommodation more frequently, resulting in lost learning days. With packed, content-heavy exam syllabuses, missed lessons lead to less developed schema, less secure knowledge and less honed skills.

The families of economically disadvantaged learners are less likely to have the financial means to provide the personal tutoring, cramming and exam practice that their more advantaged peers benefit from. And if they have reduced levels of self-belief and confidence, as many students from underserved groups do, they are more likely to crumble under exam pressure and perform poorly in timed conditions.

But given the fact that terminal tests, in the form of SATs, GCSEs and A-levels, seem here to stay as the main means of assessing learners, what can school teachers and leaders do to ensure that economically disadvantaged learners who have the potential to access high grades and assessment outcomes excel academically?

Precise diagnosis of challenges and barriers

The first step is to get to the root of the problem. Schools which have closed the attainment gap tend to be skilled at diagnosing the precise challenge or barrier standing in the way of each underserved learner. Rather than treating all PP eligible learners as a homogeneous group, they are determined to understand the lived experience of each.

So, for example, rather than talking in general or vague terms about pupils on the PP register doing less well because their attendance rate is lower, they drill down to identify the precise reason for the absences of each learner whose attendance is below par. For one it might be that they are working at a paid job in the evenings and too tired to get up in time for school, for a second it might be that they don’t come to school on days when their one set of uniform is dirty or worn, for a third that they sometimes cannot afford the transport costs to get to school and for a fourth that they are being marginalised or bullied and therefore avoiding school.

Effective ways to diagnose challenges and barriers faced by economically disadvantaged learners include:

- Home visits, or meetings on site, to get to know parents/carers and to better understand any challenges they face;

- Employing a parent liaison officer to build up relationships based on trust and mutual respect with parents;

- Allocating a staff champion to each underserved learner to talk with and listen to them in order to better understand their lived experience;

- Administering a survey with well-chosen questions to elicit barriers faced;

- Completion of a barriers audit, guiding educators to drill down to identify the specific challenges faced by each learner.

Moving from barriers to solutions

Once specific barriers have been identified, it is important to ask the question: “What does this learner need in order to excel academically?” This ensures that the focus moves from the ‘disadvantage’ to the ‘solution’ and avoids any unintentional lowering of expectations of high-performance outcomes. The danger of getting stuck on describing ‘barriers’ or ‘challenges’ is that it can excuse, or lead to acceptance of, attainment gaps.

Encouraging staff to complete a simple table like the one below can assist in identifying needs and consequent actions. In this case, an audit of barriers has identified that the learner, a Year 7 pupil, has weak digital literacy as she had very limited access to a computer in the past.

| Barrier/challenge |

Details of the issue and identification of the learner’s or learners’ need(s) |

Strategies to be adopted to meet the need |

| Weak digital literacy |

Student needs to be allocated a laptop and to receive support with understanding all the relevant functions, in order to ensure she gets maximum benefit from it for class work and home learning and can confidently use it in a wide range of learning situations. |

1:1 sessions with a sixth former to familiarise the student with the range of functions. Weekly check-ins with tutor. Calls home to monitor that she is able to confidently use the laptop for all home learning tasks. |

You can read more about strategies to close the attainment gap in Rachel’s books Obstetrics For Schools (2021) and The A-Z of Diversity and Inclusion (2024), with additional support available through HFL Education.

More from this series:

Plus: this year's NACE Conference will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

disadvantage

diversity

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

11 November 2024

|

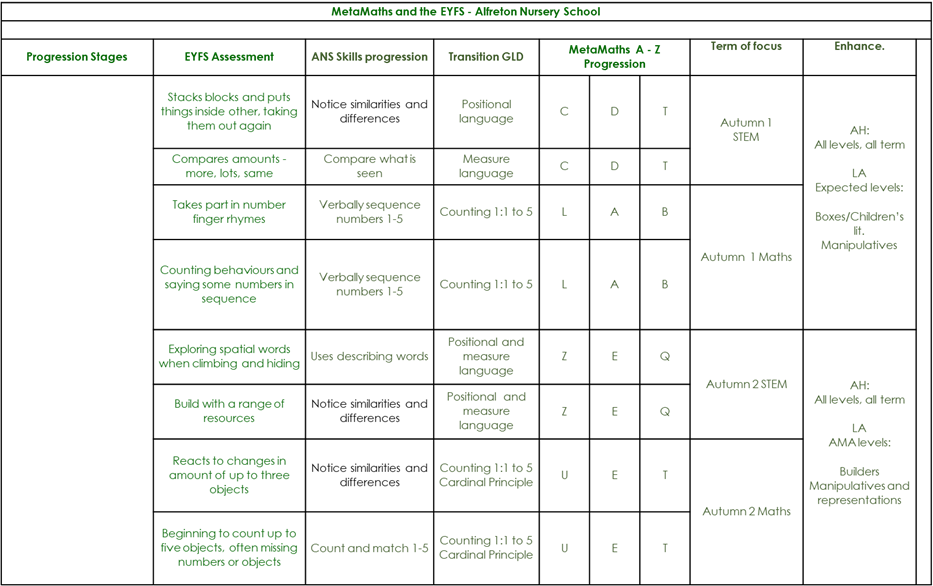

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, explores the power of metacognition in empowering young people to overcome potential barriers to achievement.

Disadvantage presents itself in different ways and has varying levels of impact on learners. It is important to remember that disadvantage is wider than children who are in receipt of pupil premium or children who have a special educational need. Disadvantage can be based around family circumstances, for example bereavement, divorce, mental health… Disadvantages can be long-term or short-term and the fluidity of disadvantage needs to be acknowledged in order for educators to remain effective and vigilant for all children, including more able learners. If we accept that disadvantage can impact any child at any time, then it is essential that we provide all children with the tools they need to navigate challenge.

More able learners are as vulnerable to the impact of disadvantage as other learners and indeed research would suggest that outcomes for more able learners are more dramatically impacted by disadvantage than outcomes for other children. A cognitive toolbox that is familiar, understood and accessible at all times, can be a highly effective support for learners when there are barriers to progress. By ensuring that all learners are taught metacognition from the beginning of their educational journey and year on year new metacognition skills are integrated, a child is empowered to maintain a trajectory for success.

How can metacognition reduce barriers to learning?

Metacognition supports children to consciously access and manipulate thinking strategies, thus enabling them to solve problems. It can allow them to remain cognitively engaged for longer, becoming emotionally dysregulated less frequently. A common language around metacognition enables learners to share strategies and access a clear point of reference, in times of vulnerability. Some more able learners can find it hard to manage emotions related to underachievement. Metacognition can help children to address both these emotional and cognitive demands.

In order for children to impact their long-term memory and fully embed metacognitive strategies, educators need to teach in many different ways. Metacognition needs to be visually reflected in the learner’s environment, supporting teachers to teach and learners to learn.

How do we do this at Alfreton Nursery School?

At Alfreton Nursery School we ensure that discourse is littered with practical examples of how conscious thinking can result in deeper understanding. Spontaneous conversations are supported by visual aids around the classroom, enabling teachers and learners to plan and reflect on thinking strategies. Children are empowered to integrate the language of metacognition as they explain their learning and strive for greater understanding.

Adults in school use metacognitive terms when talking freely to each other, exposing children to their natural use. Missed opportunities are openly shared within the teaching team, supporting future developments.

Within enrichment groups, metacognition is a transparent process of learning. Children are given metacognitive strategies at the beginning of enhancement opportunities and encouraged to reflect and evaluate at the end. Whether working indoors or outdoors, with manipulatives or abstract concepts and individually or in a group, metacognition is a vehicle through which all learners can access lesson content.

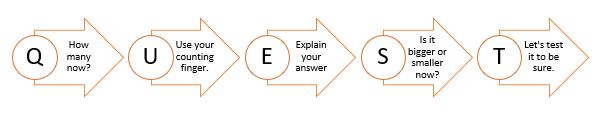

We use the ‘Thinking Moves’ metacognition framework (you can read more about this here). Creative application of this framework supports the combination of metacognition words, to make strings of thinking strategies. For example, a puppet called FRED helps children to Formulate, Respond, Explain and Divide their learning experiences. A QUEST model helps children to follow a process of Questioning, Using, Explaining, Sizing and Testing.

Metacognition supports children of all abilities, ages and backgrounds, to overcome barriers to learning. Disadvantage is thus reduced.

Moving from intent to implementation

Systems and procedures at Alfreton Nursery School serve to scaffold day to day practice and provide a backdrop of expectations and standards. In order to best serve more able children who are experiencing disadvantage, these frameworks need to be explicit in their inclusivity and flexibility. Just as every policy, plan, assessment, etc will address the needs of all learners – including those who are more able – so all these documents explicitly address how metacognition will support all learners. To ensure that visions move beyond ‘intent’ and are fully implemented, systems need to guide provision through a metacognitive lens.

Metacognition is woven into all curriculum documents. A systematic and dynamic monitoring system, which tracks the progress and attainment of all learners, ensures that children have equal focus on cognition and emotion, breaking down barriers with conscious intent.

At Alfreton Nursery School, those children who are more able and experiencing disadvantage receive a carefully constructed meta-curriculum which scaffolds their journey towards success, in whatever context that may manifest itself. Children learn within an environment where teachers can articulate, demonstrate and inculcate the power of metacognition, enabling children to be the best that they can be.

How is your school empowering and supporting young people to break down potential barriers to learning and achievement? Read more about NACE’s research focus for this academic year, and contact us to share your experiences.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

disadvantage

early years foundation stage

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

resilience

underachievement

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Raglan CiW VC Primary School,

11 November 2024

|

Marc Bowen, Deputy Headteacher and Year 5 Class Teacher at NACE member school Raglan CiW VC Primary School, shares how he has developed his classroom environment to remove potential barriers to learning for neurodivergent learners.

It has long been my experience that a proportion of the more able learners that I have had the pleasure of teaching, have also experienced the additional challenge of neurodivergent needs, whether they be diagnosed or not.

With this in mind, over the past few years I have been proactively exploring means of making my primary classroom more neurodivergent-friendly for the benefit of all learners, including those more able children that might find concentration, focus or communicating their understanding to be a challenge.

Here are a few ways in which I have tried to ensure that our learning environment enables effective learning conditions for all the children in my class, as well as benefitting those who are particularly able.

Flexible seating

Over a number of years, I have been able to increasingly vary the workspaces available in our classroom. These include:

1. The Cwtch (a well know Welsh term for a ‘hug’), which comprises a low-slung canopy under which children can sit on an array of cushions, as well as choosing their favoured colour of diffused lighting through the use of wall-mounted push-lights. This not only helps to create a more enclosed space for those who need it, but it also helps to suppress ambient noise and echoes, for those that might have sensory needs. Some of my more able learners who are challenged by distraction routinely use this space to help channel their focus.

2. The Standing Station, which does what is says on the tin! We have a high-level table which the children can easily and comfortably stand at to work. This has proven to be one of the most popular spaces and I have noted that some of my more able learners will make use of this space during the early stages of an independent task, when they might need to order or distil their thinking. The ability to move from foot to foot and move more freely appears to aid this level of thinking.

3. The Carpet Surfer Seats are ‘s’ shaped plastic seats, designed to be used when working on a carpet space. They compromise a seat, which when sat upon offers a raised work surface in front of the child. These really helped to increase the flexible seating options in the class, as the children can now easily make comfortable use of any carpet/floor space rather than struggling to find a comfortable working position. I have noted that my more able learners appreciate these when they want to work in collaboration with others but, due to their neurodivergent needs, might find the free-flow of collaborative working a challenge. The Carpet Surfer Seat gives them a defined workspace of their own, allows them to move to any more comfortable position when working collaboratively, and also provides needed stability for those more able learners I have taught who are challenged by coordination-based neurodivergence.

4. Beanbag Corner offers a solo working space on a structural (high-backed) beanbag which is close to my teacher’s base within the class. I find that this is regularly used by those more able learners who do find concentration and focus a challenge, whilst also requiring the reassuring proximity of an adult for a sense of comfort and/or to allow for informal check-ins with the teacher to tackle low-level anxiety issues.

Lighting

As with most school settings, the standard lighting fitted throughout the school is overhead, downward channel cold-white LED lighting arrays. I have noticed personally that when this is combined with the stark white table surfaces, the effect can be quite dazzling when working at these tables. The children themselves had commented on how ‘bright’ the room was, with one more able learner commenting that he ‘felt better’ during a dressing-up day when he was wearing sunglasses. This got me thinking of ways to mitigate this and, as a result, I have explored a number of different light options:

1. Dimming the overhead lights: I discovered, by accident, that if the classroom light switches are held in they act as dimmer controls for the overhead lighting. (Might be worth a try in your classroom!) It has now become standard practice for me to dim all the lighting by about 50% at the start of each day, which immediately creates a less harsh lighting environment.

2. Colour-changing rechargeable lights have also been a huge benefit. I have placed a number of these within and around my flexible working spaces, in the form of wall-mounted and table-top tap/push lights which the children can use to choose their favoured lighting conditions when working in a space. I have noticed that my more able learners typically opt for softer tones of yellow, orange or purple light.

3. Uplighters, purchased with the benefit of some funding from a local business, have had a huge impact. They allow us to create brighter working areas for those who respond well to those conditions, whilst providing diffused light, rather than overhead lights that create shadows over workspaces. In addition, these have helped to define our flexible spaces, such as the uplighter which includes a secondary directional light that sits above the Beanbag Corner.

4. Natural light is essential! We are a newbuild school but the natural lighting options are limited. As such, I make sure that all our blinds and curtains are pulled back to the extreme to ensure that as much natural light as possible can flood into the room.

Fidgets

I’m sure that some teachers will find the use of hand-held fidget objects a nightmarish challenge in a busy classroom, and if used improperly I would agree. However, the structured use of fidgets in our classroom has brought some major benefits for my more able learners who might struggle to maintain focus or settle for an extended period. We manage these by having a jar of different objects which are freely available to all children (rather than being targeted at a limited number of specific learners) and we have an open, frank conversation about how to use these at the start of the term.

Our conditions for their use are:

- If you choose to use a fidget, your focus must remain on the learning activity or discussion.

- If a fidget becomes a distraction, it is replaced in the jar immediately.

In addition, I have also experimented with different types of fidget, eliminating anything that is overly complex, noisy or too similar to a toy. Currently, the most successful types (which I now do not ‘notice’ as a distraction at any point) are rubber hand stretchers (loops that go over each digit and provide stretchy resistance), plastic wing-nuts and screw threads, and silent button/wheel fidgets (they resemble a palm-sized game controller, offering a pleasing sensation in the hand too).

Additional reading

There are some excellent online sources of information, including education-focused social media posts, where teachers share their own flexible seating/classroom environment approaches. In addition, some interesting reading that I have accessed has been:

- Fedewa, A. L., Davis, M. A., & Ahn, S. (2015). The Effects of Physical Activity and Physical Classroom Environment on Children’s On-Task Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review.

- Kroeger, S., & Schultz, T. (2020). Sensory Spaces: Creating Inclusive Classrooms for Students with Sensory Needs. Inclusive Education Journal.

- Rands, M. L., & Gansemer-Topf, A. (2017). The Role of Classroom Environment in Student Engagement. Journal of Education Research.

How is your school helping to break down barriers to learning?

This year NACE’s research programme is exploring the ways in which schools can help to remove potential barriers to success for more able learners. Find out more and get involved.

Tags:

disadvantage

dual and multiple exceptionality

KS1

KS2

underachievement

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Jonathan Doherty,

19 May 2022

|

Dr Jonathan Doherty, NACE Associate

Covid-19 has presented schools with unprecedented challenges. Pupils, parents and teachers have all been affected, and the wider implications in schools are far from over. From May 2020, over 1.2 billion learners worldwide have experienced school closures due to Covid-19, which corresponds to 73.8% of enrolled learners (Muller & Goldenberg, 2021). The pandemic continues to have a significant effect in all phases of our education system. This blog post captures some key messages from research into the effects of Covid-19 over the past two years and highlights the effects it has had on young people – particularly on the development of language and communication skills.

1. The pandemic negatively affected achievement. Vulnerable pupils and those from economically deprived backgrounds were most affected.

When pupils do not attend school (whilst acknowledging that much great work is done at home), the disruption has a negative impact on their academic achievement (Sims, 2020).

The disrupted periods of partial school closures in England took a toll academically. DfE research (Pupils' progress in the 2020 to 2022 academic years) showed that in summer 2021, pupils were still behind in their learning compared to where they would otherwise have been in a typical year. Primary school pupils were one month behind in reading and around three months behind in maths. Data for secondary pupils suggest they were behind in their reading by around two months.

Primary pupils eligible for free school meals were on average an additional half month further behind in reading and maths compared to their more advantaged peers. Research has highlighted that the attainment gap between disadvantaged children and others is now 18 months by the end of Key Stage 4. Vulnerable pupils with education, health and care (EHC) plans scored 3.62 grades below their peers in 2020 and late-arriving pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) were 1.64 grades behind those with English as a first language (Hunt et al., 2022).

2. Remote teaching during Covid changed the nature of learning – including reduced learning time and interactions – further widening existing gaps.

‘Learning time’ is the amount of time during which pupils are actively working or engaged in learning, which in turn is connected to academic achievement. Pre-pandemic (remember those days?!), the average mainstream school day in England for primary and secondary settings was around six hours 30 minutes a day. The difference between primary and secondary is minimal and averages out at 9 minutes a day.

During the period up to April 2021, mainstream pupils in England lost around one third of learning time (Elliot Major et al., 2021). We know that disadvantaged pupils continue to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Levels of lost learning remain higher for pupils in more deprived areas.

School provision for online learning changed radically since the beginning of the first lockdown. Almost all pupils received some remote learning tasks from their teachers. Just over half of all pupils taught remotely did not usually have any online lessons, defined as live or real-time lessons. Offline provision, such as worksheets or recorded video, was much more common than live online lessons, but inevitably reduced the opportunities for pupil-pupil interactions.

Parents reported that for most pupils, time spent on schoolwork fell short of the expected school day (Eivers et al., 2020). Pupil participation was, on average, poorer amongst those from lower income families and those whose parents had lower levels of education (Eivers et al., 2020). Families from higher socio-economic backgrounds spend more financially to support their children’s online remote learning. At times, technological barriers, as well as significant differences in the amount of support pupils received for learning at home, resulted in a highly unequal experience of learning during this time.

3. There has been a negative impact on pupils’ wellbeing, socio-emotional development and ability to learn.

A YoungMinds report in 2020 reinforced the effect of the pandemic on pupils’ mental health. In a UK survey of participants aged up to 25 years with a history of mental illness, 83% of respondents felt that school closures had made their mental illness worse. 26% said they were unable to access necessary support.

Schools play a key role in supporting children who have experienced bereavement or trauma, and socio-emotional interventions delivered by school staff can be very effective. Children with emotional and behavioural disorders also have significant difficulties with speaking and understanding, which often goes unidentified (Hollo et.al., 2014).

The experience of lockdown and being at home is a stressful situation for some children, as is returning to school for some children. While some studies found that children are not affected two to four years later, other studies suggest that there are lasting effects on socio-emotional development (Muller & Goldenberg, 2021).

Stress also challenges cognitive skills, in turn affecting the ability to learn. Trauma, emotional and social isolation, all well-known during the lockdown, are still too frequent. The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain which is responsible for higher-order thinking and decision-making, is the brain region most affected by stress. Stress-related impairments to the prefrontal cortex display impaired memory retrieval (Vogel & Schwabe, 2016) and difficulties with executive skills such as planning, problem solving and monitoring errors (Gibbs et al., 2019).

4. National restrictions have curtailed the pandemic but had an adverse effect on communication and language.

Covid-19 and the associated lockdowns have had a huge impact on children’s speaking and listening skills. We are only beginning to understand the scale of this. Preventative measures such as the wearing of face masks in school, social distancing and virtual lessons, all designed to address contagion concerns, have negatively impacted on communication in all the school phases.

Face masks cover the lower part of the face, impacting on communication by changing sound transmission. They remove visible cues from the mouth and lips used for speech-reading and limit visibility of facial expressions (Saunders, 2020). Speech perception involves audio-visual integration of information, which is diminished by wearing masks because articulatory gestures are obscured. Children with hearing loss are more dependent on lip-reading; loss of this visual cue exacerbates the distortion and attenuation effects of masks.

Social interaction is also essential for language development. Social distancing restrictions on large group gatherings in school have affected children’s deeper interactions with peers. “Peer talk” is an essential component of pragmatic language development and includes conversational skills such as turn taking and understanding the implied meaning behind a speaker’s words, and these have also been reduced (Charney, 2021).

How bad is the issue? A report from the children’s communication charity I CAN estimates that more than 1.5 million UK children and young people risk being left behind in their language development as a direct result of lost learning in the Covid-19 period. Speaking Up for the Covid Generation (I CAN, 2021) reported that the majority of teachers are worried about young people being able to catch up with their speaking and understanding. Amongst its findings were that:

- 62% of primary teachers surveyed were worried that pupils will not meet age-related expectations

- 60% of secondary teachers surveyed were worried that pupils will not meet age-related expectations

- 63% of primary and secondary teachers surveyed believe that children who are moving to secondary school will struggle more with their speaking and understanding, in comparison to those who started secondary school before the Coronavirus pandemic.

Measures taken to combat the pandemic have deprived children of vital social contact and experiences essential for developing language. Reduced contact with grandparents, social distancing and limited play opportunities mean children have been less exposed to conversations and everyday experiences. Oracy skills have been impacted by the wearing of face coverings, fewer conversations with peers and adults, hearing fewer words and remote learning where verbal interactions are significantly reduced.

Teachers are now seeing the impact of this in their classrooms. The I CAN report findings show that the majority of teachers are worried about the effect that the pandemic has had on young people’s speech and language. As schools across the UK start on their roads to recovery and building their curricula anew, this evidence reveals the major impact the pandemic has had on children’s speaking and understanding ability. The final Covid-19-related restrictions in England have now been removed, but for many young people and families, this turning point does not mark a return to life as it was before the pandemic. There is much to do now to prioritise communication.

Join the conversation…

As schools move on from the pandemic and seek to address current challenges, close gaps, and take oracy education to the next level, NACE is focusing on research into the role of oracy within cognitively challenging learning. This term’s free member meetup will bring together NACE members from all phases and diverse contexts to explore what it means to put oracy at the heart of a cognitively challenging curriculum – read more here.

Plus: to contribute to our research in this field, please contact communications@nace.co.uk

References

Charney, S.A., Camarata, S.M. & Chern, A. (2021). Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Communication and Language Skills in Children. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2, Vol. 165(1) pp. 1-2.

Elliot Major, L., Eyles, A. & Machin, S. (2021). Learning Loss Since Lockdown: Variation Across the Home Nations [online]. Available at: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepcovid-19-023.pdf

Eivers, E., Worth, J. & Ghosh, A. (2020). Home learning during Covid-19: findings from the Understanding Society longitudinal study. Slough: NFER.

Gibbs L., Nursey, J., Cook J. et al. (2019). Delayed disaster impacts on academic performance of primary school children. Child Development 90(4): pp. 1402-1412.

Hollo, A., Wehby, J. H., & Oliver, R. M. (2014). Unidentified language deficits in children with emotional and behavioural disorders: a meta-analysis. Exceptional Children 80 (2), pp.169-186.

Hunt, E. et al. (2022) COVID-19 and Disadvantage. Gaps in England 2020. London: Education Policy Institute. Nuffield Foundation.

I CAN (2021) Speaking Up for the Covid Generation. London: I CAN.

Muller, L-M. & Goldenberg, G. (2021) Education in times of crisis: The potential implications of school closures for teachers and students. A review of research evidence on school closures and international approaches to education during the COVID-19 pandemic. London: Chartered College of Teaching.

Saunders, G.H., Jackson, I.R. & Visram, A.S. (2020): Impacts of face coverings on communication: an indirect impact of COVID-19. International Journal of Audiology, DOI: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1851401

Sims, S. (2020) Briefing Note: School Absences and Pupil Achievement. UCL. Available at: https://repec-cepeo.ucl.ac.uk/cepeob/cepeobn1.pdf

Vogel, S. & Schwabe, L. (2016) Learning and memory under stress: implications for the classroom. Science of Learning 1(1): pp.1-10.

YoungMinds (2020) Coronavirus: Impact on young people with mental health needs. Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/media/3708/coronavirus-report_march2020.pdf

Tags:

confidence

disadvantage

language

lockdown

oracy

pedagogy

remote learning

research

resilience

underachievement

vocabulary

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Chris Yapp,

26 August 2020

|

This blog post is based on an article originally published on LinkedIn on 16 August 2020 – click here to read in full.

The fallout from A-level and GCSE results will be uncomfortable for government and upsetting and challenging for teachers and students alike. Arguments over whether this year’s results are robust and fair miss one key issue.

Put simply: "Has the exam system in England ever been robust and fair for individual pupils?"

For those of us who did well in exams and whose children also did well, it is too easy to be confident. Accepting that our success and others’ failure is a systemic problem, not a result of competence and capability, is not easy.

Let me be clear: I do not have confidence in the exam system in England as a measure either of success or capability.

[…] Try this as a thought experiment. Imagine that I gave an exam paper submission to 100 examiners. Let me assume that it "objectively" is a C grade.

Would all 100 examiners give it a C? If not, what is the spread? Is the spread the same for English literature, physics and geography, as just three examples? If you cannot provide clear evidenced answers to these questions, how can you be confident that the system is objective?

If we look at the examiners, the same challenge appears. Are all examiners equally consistent in their marking, or do some tend to mark up or down? Where is the evidence, reviewed and published to demonstrate robustness?

We also know that the month you are born still has an effect on GCSE grades. What is robust about that?

[…] I have known children who have missed out on grades after divorce, separation and death of parents, siblings and pets. I cannot objectively give a measure of the impact, but then neither can the exam system. I would add that I suspect a classmate of mine missed out because of hayfever. Children with health issues such as leukaemia and asthma whose schooling is disrupted have had their grades affected every year, not just this one.

So, the high stakes exam system is, for me, a winner-takes-all loaded gun embedding inequality and privilege in the outcomes.

Can we do better? Well, if we want to use exams, then each paper needs to be marked by say five independent assessors. If they all agree on a "B" then that is a measure of confidence. This is often a model used for assessing loans, grants and investments in businesses. It does not guarantee success of course, but what it does is reduce reliance on potentially biased individuals. If I was an examiner and woke up today in a foul mood, would I mark a paper the same today as yesterday? I would not bet on it.

The really interesting cases in my experience are where you get 2As, a C and 2Ds, for instance. In my experience, I've seen it more often in "creative subjects", but some non-traditional thinkers in subjects like mathematics (a highly creative discipline, by the way) often don't fit the narrow models of assessment of our exam system. The problem with this example of bringing people together to try get a consensus on a "B" is that it eliminates the value that comes from the diverse views and the richness of the different perceptions.

So, for me, for a system to be robust it has to have more than one measure to allow the individual, parents, universities, FE and employers access to a richer view of an individual. If someone got an ABBCD in English that is as interesting as someone who got straight Bs.

[…] There are already models that command respect in grading skill levels. Parents are quite happy if a child is doing grade 6 piano and grade 2 flute at the same time. They are quite happy for a child to sit when ready and have the chance to resit. Yet in the school setting the pressure is there for a child to be at level 8 say for all subjects. That puts unnecessary pressure on pupils, teachers and schools.

Imagine how society would react if you could only take the driving test once at 17 and barriers were raised to stop you retaking it.

[…] This year’s bizarre algorithmic system is not robust, but then we have never had a robust system as far as I am concerned. Let's open our eyes and build something that we should have more confidence in. Carpe diem.

Join the discussion: share your views in the comments below (member login required).

Tags:

assessment

disadvantage

KS4

KS5

lockdown

policy

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elizabeth Allen CBE,

11 June 2020

|

Liz Allen CBE, NACE Trustee

Listening in to over 200 school leaders, teachers and young people in online forums and in personal conversations, I am hearing a recurring theme: “Some children have done better without me teaching them.” Some teachers add, “…which is a worry.” Most are keen to explore the reasons why some children are thriving on home learning, when many appear to be struggling. While it is vital that the reasons for this struggle are identified and addressed, there is also much that school leaders and teachers can learn from the “rising stars” – young people who were not identified for a particular ability, skill or expertise in the classroom but who are blossoming at home, surprising their teachers.

Why were they not noticed in school? Why are they thriving at home? What can we learn from them, for our future practice, as we prepare for more students to return to the classroom?

Limiting factors within schools

Although the rising stars appear to come from all phases, types of school and a range of socio-economic contexts, common limiting factors in their schools’ culture and organisation are emerging:

- Less confident schools, that are focused on exam outcomes, attendance targets and rigorous behaviour management structures, where young people are lost in the drive for data;

- Schools with highly structured, frequent testing, where young people have too few opportunities to be inspired, to be creative, or to learn in depth;

- Schools with strict ability grouping and differentiation practices, built on assumptions of ability;

- Prescriptive schemes of work that leave little scope for teachers’ creativity, or for young people’s expertise – there is no time for deep learning in a classroom where quantity matters more than mastery;

- Pedagogies that are teacher-focused and controlled, leaving too little scope for young people to become independent researchers, problem solvers or learning leaders;

- Schools that misconstrue presentations of negative learning character as misbehaviour: the window-gazer, who finds the ideas inside her head more interesting but has no chance to share or explore them; the disruptive, who wants to let the teacher know that he is capable of much more challenging stuff but doesn’t know how to say it; the angry or withdrawn, who doesn’t understand and can’t process the work because her learning needs have not been recognised; the passive, unconfident, who finds the classroom crowded and oppressive;

- Schools that have an extended core curriculum at the expense of the creative/expressive arts, design and PE, where young people have little opportunity to grow into disciplined, collaborative, creative learners and critical thinkers, or to have their creative/expressive/physical abilities and talents acknowledged and celebrated.

Why are some students thriving at home?

Teachers are telling anecdotes about the “rising stars” they are noticing and are asking their pupils why they are more engaged and making more progress.

What is striking is the deepening mutual trust and respect which is clear in their voices:

“I am encouraging students to engage with their world, to discover new resources. They are enjoying daily, short skills practices that they self-assess with the help of a simple quiz. They enjoy gaining mastery, rather than marks.”

“I have discovered hidden stars from having personal learning conversations. I was bogged down in a mountain of marking and concerned that only 30% of my students were submitting any work. So I decided to abandon the prescribed written feedback procedure and give each student a two-minute verbal personal moment each week. I didn’t realise how important it was for students to see me, to be called by their name and to feel they mattered to me. I have been really surprised by how able many of them are.”

“I find that quiet students are benefitting from being at home, without the pressures and noise of school. I didn’t realise how capable they are and am wondering why they are not in the top set.”

“I’m in a school where we are expected to maintain the full curriculum and schemes of work. We soon discovered that it was impossible, so my department re-designed the study programme, built on two principles: students can follow their own interests; they should create something – grow it, design it, build it, then teach your teacher and class what you know. We are on hand with advice and we have created a huge bank of resources for them to use, including examples of the department’s special interests and their own creations. Some great experts are emerging – both students and staff!”

Creative writing is a struggle for many young people, who often have a fixed view “I can’t do it.” One Year 5 pupil was very anxious about having to do creative writing tasks at home. “In school, there’s a plan on the board and I can put my hand up when I’m stuck.” Finding it easy to come up with “lots of ideas”, but getting stuck on how to develop them further, he is enjoying sharing his ideas at home and on FaceTime with his friends. “It’s much nicer than at school and I think I am getting much better.”

One-to-one tutorials are building young people’s confidence and respectful relationships with their teachers, who are able to see their capacity. A Year 12 tutor was struck with how powerful the tutorial can be: “It’s fascinating to listen to him. He has great insight and knows more than I do!” Another Year 12 student is appreciating the value of having a trusting and mutually respectful relationship with her tutors. She had a difficult pathway through the GCSE years, excelling in the subjects where she had private one-to-one tuition but unable to achieve her best outcomes in the rest. Now, through daily contact with her tutors, personal advice whenever she wants it, constant collaborative learning opportunities with her peers and with new-found confidence in her capacity, she is totally engaged with her Year 12 studies. “I miss being in school and I certainly miss my friends, but the work is going well. And I am looking forward to going in after half-term for real, live tutorials.”

“At Key Stage 3, introverted students remain mute for the lesson, reluctant to engage or speak but still submit a high standard of work. In contrast, when speaking to these students on a one-to-one basis, they will be forthcoming with how they are feeling. One ‘live’ call a week from their tutor is making a big difference to their progress and their wellbeing. Key Stage 4 and 5 students have adapted exceptionally well. I should mention that they are used to independent learning: they do a lot of reading around their subjects.”

What can we learn for our future practice?

Good friends from the retired headteachers’ community are entertaining each other with tales from the home front. They are discovering that IT is not a mysterious world inhabited by the young but an exciting avenue into following their interests and exploring new places: playing in a huge online orchestra, singing in Gareth Malone’s choir, visiting the theatres, galleries, faraway lands. And they are clearing the loft! An opportunity to throw out unneeded items that must have been useful once, but you have forgotten why – but also to rediscover lost treasures, hidden gems, that deserve to be brought back into the home, polished and put to good use. Perhaps this period of home schooling is our chance to clear out the curriculum and pedagogy loft, to discard what is not useful and to rediscover and polish up the gems of our principles and practice in the light of what young people are telling us.

NACE’s core principles include the statements:

- Providing for more able learners is not about labelling, but about creating a curriculum and learning opportunities which allow all children to flourish.

- Ability is a fluid concept: it can be developed through challenge, opportunity and self-belief.

In its chapter on Teaching for Learning, The Intelligent School (2004) presents a profile of the Learning and Teaching PACT – what the learner and the teacher bring to learning and teaching and, in turn, what they both need for the PACT to have maximum effect. Features of the PACT are visible in the accounts of rising stars, where both learner and teacher bring:

- A sense of self as learner;

- Mutual respect and high expectations;

- Active participation in the learning process;

- Reflection and feedback on learning;

And where the teacher brings:

- Knowledge, enthusiasm, understanding about what is taught and how;

- The ability to select appropriate curriculum and relevant resources;

- A design for teaching and learning fit for purpose;

- An ability to create a rich learning environment.

“Place more emphasis […] on the microlevel of things […] It encourages a culture that is more open and caring […] It requires genuine connection.” – Leading in a Culture of Change (2004)

Chapter 4 of Michael Fullan’s Leading in a Culture of Change is entitled “Relationships, Relationships, Relationships”. Young people are letting their teachers know that personal conversations are enabling their learning. One group of Key Stage 3 students have asked their teachers to stop using PowerPoint presentations, which they feel unable to understand – “But it all makes sense when we talk about it with you.” Learning conversations may be a rediscovered gem in some schools, worth bringing down from the loft of forgotten treasure.

From the same chapter: “When you set a target and ask for big leaps in achievement scores, you start squeezing capacity in a way that gets into preoccupation with tests […] You cut corners in a way that ends up diminishing learning […] I want steady, steady, ever deepening improvement.”

Motivation comes from caring and respect: “tough empathy” in Fullan’s terms. The rising stars are being noticed in a learning environment free from classroom tests and marking. We may need to take a close look at assessment practices in our loft clearance and rediscover the gems of self-assessment, academic tutorials, vivas and reflective discourse.

Can we improve young people’s chances of stardom by considering some fresh thinking, as we prepare for more of them to return to school?

- What will “homework” mean? Can we build on what we are learning about best practice in home schooling?

- How will we inspire (rather than push) young people to high aspirations and outcomes?

- How can we listen better and build respectful, healthier learning relationships?

- Can we design learning for depth and mastery rather than for assessment/testing and quantity?

- How can we open up the curriculum and learning to creativity?

- How can we exemplify and model best learning in our lessons?

- How can we give young people time, resources and personal space to learn how to learn, to become the best they can be?

References and further reading:

- The Intelligent School (Gilchrist, Myers & Reed, 2004)

- Leading in a Culture of Change (Michael Fullan, 2001)

- Engaging Minds (Davis, Sumara & Luce-Kapler, 2008)

- Knowledge and The Future School (Young, Lambert, Roberts & Roberts, 2014)

- Reassessing Ability Grouping (Francis, Taylor & Tereshenko 2020)

This article was originally published in the summer 2020 special edition of NACE Insight, as part of our “lessons from lockdown” series. For access to all past issues, log in to our members’ resource library.

Tags:

confidence

curriculum

identification

independent learning

leadership

lockdown

remote learning

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elaine Ricks-Neal,

04 February 2019

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

“Character” may be the latest buzzword in education – but it’s long been at the core of the NACE Challenge Framework, as NACE Challenge Award Adviser Elaine Ricks-Neal explains…

Increasingly schools are focusing on the development of “character” and learning dispositions as performance outcomes. Ofsted is also making it clear that it will look more at how well schools are developing resilient, well-rounded, confident young learners who will flourish in society.

The best schools, irrespective of setting, have always known the importance of this. And this focus on character has long been at the heart of the NACE Challenge Framework – a tool for school self-review and improvement which focuses on provision for more able learners, as part of a wider programme of sustainable school improvement and challenge for all.

Here are 10 key ways in which the Framework supports the development of school-wide approaches, mindsets and skills for effective character education:

1. “Can-do” culture

The NACE Challenge Framework embeds a school-wide “You can do it” culture of high expectations for all learners, engendering confidence and self-belief – prerequisites for learning.

2. Raising aspirations

The Framework challenges schools to raise aspirations for what all learners could achieve in life, irrespective of background. This is especially significant in schools where learners may not be exposed to high levels of ambition among parents/carers.

3. Curriculum of opportunity

Alongside a rich curriculum offer, the Framework asks schools to consider their enrichment and extracurricular programmes – ensuring that all learners have opportunities to develop a wide range of abilities, talents and skills, to develop cultural capital, and to access the best that has been thought and said.

4. Challenge for all

At the heart of the Framework is the goal of teachers understanding the learning needs of all pupils, including the most able; planning demanding, motivating work; and ensuring that all learners have planned opportunities to take risks and experience the challenge of going beyond their capabilities.

5. Aspirational targets

To ensure all learners are stretched and challenged, the Framework promotes the setting of highly aspirational targets for the most able, based on their starting points.

6. Developing young leaders

As part of its focus on nurturing student voice and independent learning skills, the Framework seeks to ensure that more able learners have opportunities to take on leadership roles and to make a positive contribution to the school and community.

7. Ownership of learning

The Framework encourages able learners to articulate their views on their learning experience in a mature and responsible way, and to manage and take ownership of their learning development.

8. Removing barriers

The Framework has a significant focus on underachievement and on targeting vulnerable groups of learners, setting out criteria for the identification of those who may have the potential to shine but have barriers in the way which need to be recognised and addressed individually.

9. Mentoring and support

Founded on the belief that more able and exceptionally able learners are as much in need of targeted support as any other group, the Framework demands that schools recognise and respond to their social and emotional and learning needs in a planned programme of mentoring and support.

10. Developing intrinsic motivation

Beyond recognising individual talents, the Framework promotes the celebration of success and hard work, ensuring that learners feel valued and supported to develop intrinsic motivation and the desire to be “the best they can.”

Find out more… To find out more about the NACE Challenge Development Programme and how it could support your school, click here or get in touch.

Tags:

aspirations

character

disadvantage

enrichment

mentoring

mindset

motivation

resilience

school improvement

student voice

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|