Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Matthew Williams,

21 May 2020

|

Dr Matthew Williams, Access Fellow at Jesus College, Oxford, shares his belief in the importance of “confident creativity” as the key to developing sustained effort and a lasting love of learning.

I am a fellow and tutor in politics at Jesus College, Oxford, and I’d like to share some thoughts on how students can be energised to “work harder”. Specifically how do we encourage sustained effort, leading to improved attainment? What follows are reflections on a decade of teaching and schools outreach work at Oxford and Reading Universities. There is a mixture of theory here, but readers should be warned there will also be big dollops of unscientifically personal recall.

As an undergraduate student of politics at the University of Bristol, the most significant learning experience came during seminars on the British Labour Party. At first, I was fairly indifferent on the subject, but the seminars entailed a mixture of traditional essay-based research and more flashy simulation-based learning. On the latter, we had a Cabinet meeting in our seminar with each of us playing real characters. I was Jim Callaghan, and I had to prepare Cabinet papers, work out strategy and tactics in order to win a fight with, in particular, Tony Benn!

The experience brought everything to life. The theoretical and practical came together, and I have to this day never forgotten the specifics of that fight in late 1976. On reflection, the primary effect of the simulation was the transformation of the subject matter from work into study. Studying is not work in the sense of being performed for someone or something else’s benefit. Instead, studying is intrinsically pleasurable. Whilst many students are motivated by long-term payoff (career prospects, reputation, power etc) many, like me, see more immediate feedback. This particular teaching style transformed the 9am walk to lectures from a reluctant trudge to an enthusiastic commute. It was revelatory.

Demystifying the means of achieving distinction

Ever since those seminars I have aspired in my personal and professional life to transform work into study. The key ingredient used by the seminar tutor was positive motivation. He made clear his interest was in us and our ideas, rather than our performance in the exam and the reputation of the university. As such, he did not want us to regurgitate the literature, rather he wanted us to know the literature so we could analyse it critically whilst presenting our own original contributions.

This was liberating. All of sudden the most complex elements of social democratic ideology and post-industrial economics were not prohibitively intimidating; they were required reading for anyone wishing to have their voice heard. In this process, we had to acknowledge we could contribute to a debate despite our relative academic inexperience. The tutor was clear: good ideas are not the monopoly of tenured professors. If we wanted to, we were perfectly capable of contributing original theoretical insights and empirical discoveries. To achieve the distinction of a first class degree our work had to be creative and, crucially, the tutor made clear we were all capable of distinction if we wanted it.

This teaching style resonated with me because it demystified the means of achieving distinction. Previously, I had assumed distinction was a matter of talent, intelligence and luck – none of which I felt much graced with. Subsequently, I realised distinction meant creativity, and creativity needed energy and self-confidence.

Understanding the importance of “confident creativity”

“Confident creativity” is not my first teaching philosophy. For a job application in 2012 I proposed a similar philosophy focused on positive motivation and confident application of skills. Whilst this is seemingly the same philosophy, the older version was predicated on teaching as the transmission of knowledge, where now I see teaching more as developing and nurturing key skills. The transmission model prioritised interesting learning materials as the fundamental variable; whilst I still consider the materials to be important, they are secondary to the students’ nurtured development of complex skills. When students internalise the skills of processing complex information, they will find interest in practically all relevant materials, without the need for unrepresentatively “sexy” content. Even a 1970s Cabinet meeting can become enthralling!

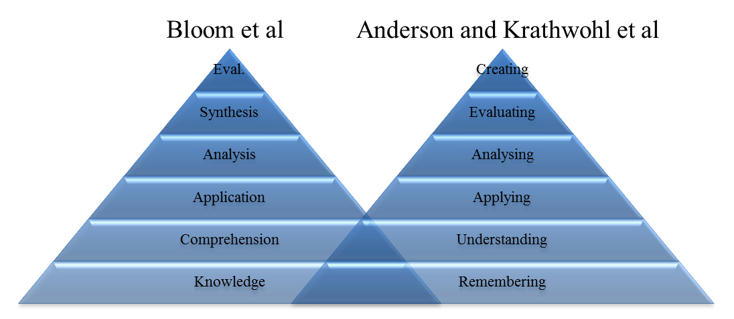

The key change in my teaching philosophy has been the realisation that motivating students should encourage a sense of independent intellectual development. This change in emphasis can be represented as a synthesis of two learning outcome hierarchies, proposed by Bloom et al (left pyramid) and Anderson & Krathwohl et al (right pyramid).

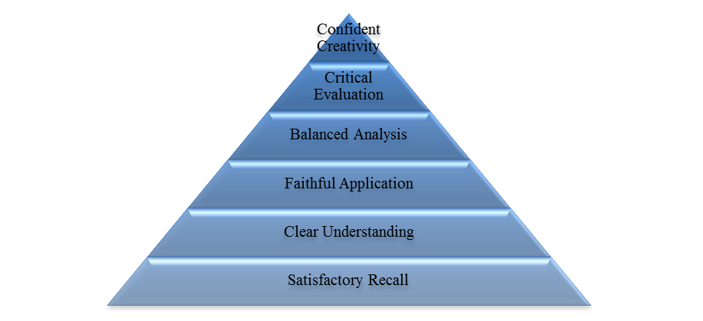

I propose a synthesis of these taxonomies, fleshed out with qualifying adjectives:

Including qualifying adjectives in Anderson & Krathwohl et al’s hierarchy allows us to assess the learning objectives in greater detail, with clearer observable implications. Adding an extra level of nuance to the concepts enriches their meaning, without losing the parsimony and clarity which are such key strengths of the original taxonomy. The addition of adjectives could be criticised as creating needless tautologies – if, for instance, we assume confidence is a necessary condition of creativity. However, creativity can be achieved without confidence if it is accidental and the student is unaware of the merits of their creativity. We need to aim for confident creativity because it is significantly more sustainable and transferable for a student to create in confidence than to be creative by accident or with heavy-handed guidance.

Transferring this approach to different contexts

Critical reflexivity is a very personal journey, and the results of my personal reflections may not be transferable. Even the phrase “teaching philosophy” connotes a sense of philosophy as retroactive rationalisation of one’s own perspective, as opposed to the analytic use of the term as a clear, open and rigorous system of thought. As Nancy Chism states, somewhat ironically, “One of the hallmarks of a philosophy of teaching statement is its individuality.” Whilst a teaching philosophy is developed through self-reflection, it requires self-awareness before it can be applied to others. Notably, teachers are somewhat unusual in their relationship with knowledge. They relish the acquisition of knowledge as an intrinsic good, where motivation to learn is rarely absent and the desire to contribute is second nature.

But what is good for the goose is not necessarily good for the gander. For many students school and college is first and foremost about acquiring qualifications, and therefore simply an instrument for career advancement. As such, not all students want to achieve distinction, nor see the value in risking creative contributions when a less resistant path exists. For such students there is a risk that emphasis on creativity will alienate them from the subject and the teacher. Furthermore, the development of my teaching philosophy has primarily taken place at an elite university, where boundary-pushing and intellectual confidence is far less risk-laden than in other contexts. The unflinchingly liberal environment at Oxford ascribes considerable value to intellectual creativity, perhaps at the expense of consolidation. Yet there is little utility in a teaching philosophy that is contingent on where and for whom it applies.

Nevertheless, these concerns are surmountable. Yes, academics perhaps have a gilded view of knowledge, but only because they have internalised the skills of contributing knowledge to the point where it has become (for the most part) a pleasure. It is incumbent on academics to encourage students towards a similar relationship with the world. Whilst not all students will want or feel able to contribute genuine insights, “confident creativity” is the apex of the pyramid and there are other levels of learning available to differentiate between learners. The ambition should be to encourage confident creativity, but “critical evaluation” or “balanced analysis” will be satisfactory outcomes for many students. Learners should not be forced to fit a teaching style that alienates them and a degree of differentiation between students will be required with the proviso that “confident creativity” is unambiguously the preferred goal and should be encouraged as far as possible.

Ultimately, the point of education is to equip individuals with the skills to speak for themselves. This is best achieved when we mix up teaching styles, and jolt work into study.

References

- Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R., Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (eds) (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. (New York: Addison Wesley Longman Inc).

- Bloom, B.S., Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (eds) (1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals – Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain. (London, WI: Longmans, Green & Co Ltd).

- Chism, N. V. N. (1998) “Developing a Philosophy of Teaching Statement.” in Essays on Teaching Excellence 9(3) (Athens GA: Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education).

- Pratt, D.D., & Collins, J.B. (2000) ‘The teaching perspectives inventory: Developing and testing an instrument to assess teaching perspectives’ Proceeding of the 41st Adult Education Research Conference.

About the author

Dr Matthew Williams is Access Fellow at Jesus College, University of Oxford, where he teaches and conducts research in the field of political studies. Known as “the Welsh College”, Jesus College has a long history of working with schools in Wales and has recently taken on responsibility for delivering the university’s outreach and access programmes across all regions of Wales. Read more.

Live webinar: “Developing sustained effort in able learners”

On 2 July Dr Williams is leading a free webinar for NACE members in Wales, exploring approaches to developing confident creativity and motivating learners to be ambitious for themselves. This is part of our current series supporting curriculum development in Wales. Find out more and book your place.

Tags:

aspirations

confidence

CPD

creativity

independent learning

Oxbridge

Oxford

pedagogy

Wales

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By University of Oxford (Oxplore),

06 February 2020

|

The University of Oxford’s Oxplore website offers free resources to get students thinking about and debating a diverse range of “Big Questions”. Read on for three ways to get started with the platform, shared by Oxplore’s Sarah Wilkin…

Oxplore is a free, educational website from the University of Oxford. As the “Home of Big Questions”, it aims to engage 11- to 18-year-olds with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom. Big Questions tackle complex ideas across a wide range of subjects and draw on the latest research from Oxford.

Oxplore’s Big Questions reflect the kind of interdisciplinary and critical thinking students undertake at universities like Oxford. Each question is made up of a wide range of resources including: videos, articles, infographics, multiple-choice quizzes, podcasts, glossaries, and suggestions from Oxford faculty members and undergraduates.

Questioning can take many different forms in the classroom and is a skill valued in most subjects. Developing students’ questioning skills can empower them to:

- Critically engage with a topic by breaking it down into its component parts;

- Organise their thinking to achieve certain outcomes;

- Check that they are on track;

- Pursue knowledge that fascinates them.

Here are three ways Oxplore’s materials can be used to foster questioning and related skills…

1. Investigate what makes a question BIG

A useful starting point can be to get students thinking about what makes a question BIG. This can be done by displaying the Oxplore homepage and encouraging students to create their own definitions of a Big Question:

- Ask what unites these questions in the way we might approach them and the kinds of responses they would attract.

- Ask why questions such as “What do you prefer to spread on your toast: jam or marmite?” are not included.

- Share different types of questions like the range shown below and ask students to categorise them in different ways (e.g. calculable, personal opinion, experimental, low importance, etc.). This could be a quick-fire discussion or a more developed card-sort activity depending on what works best with your students.

2. Answer a Big Question

You could then set students the challenge of answering a Big Question in groups, adopting a research-inspired approach (see image below) whereby they consider:

- The different viewpoints people could have;

- How different subjects would offer different ideas;

- The sources and experts they could ask for help;

- The sub-questions that would follow;

- Their group’s opinion.

If you have access to computers, students could use the resources on the Oxplore website to inform their understanding of their assigned Big Question. Alternatively, download and print out a set of our prompt cards, offering facts, statistics, images and definitions taken from the Oxplore site:

Additional resources:

This activity usually encourages a lot of lively debate so you might want to give students the opportunity to report their ideas to the class. One reporter per group, speaking for one minute, can help focus the discussion.

3. Create your own Big Questions

We’ve found that no matter the age group, students love the opportunity to try thinking up their own Big Questions. The chance to be creative and reflect on what truly fascinates them has the appeal factor! Again, you might want to give students the chance to explore the Oxplore site first, to gain some inspiration. Additionally, you could provide word clouds and suggested question formats for those who might need the extra support:

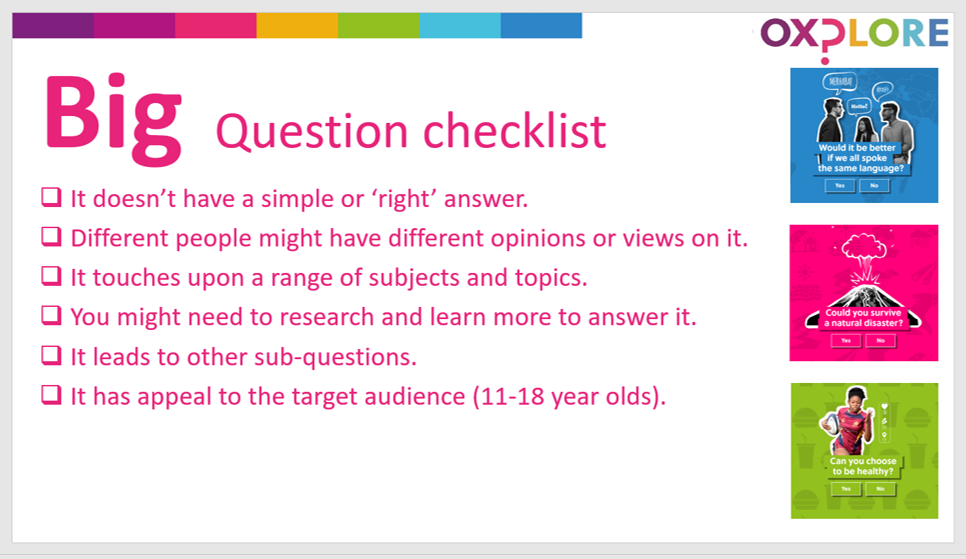

To encourage students to think carefully and evaluate the scope of their Big Question, you could present them with a checklist like the one below:

Extension activities could include:

- Students pitching their Big Question to small groups or the class (Why does it interest them? What subjects could it include? etc);

- This could feed into a class competition for the most thought-provoking Big Question;

- Students could conduct a mini research project into their Big Question, which they then compile as a homework report or present to the class at a later stage.

Take it further: join a Big Question debate

Each term the Oxplore team leads an Oxplore LIVE event. Teachers can tune in with their classes to watch a panel of Oxford academics debating one of the Big Questions. During the event, students have opportunities to send in their own questions for the panel to discuss, plus there are competitions, interactive activities and polls. Engaging with Oxplore LIVE gives students the chance to observe the kinds of thinking, knowledge and questions that academics draw upon when approaching complex topics, and they get to feel part of something beyond the classroom.

The next Oxplore LIVE event is on Thursday 13 February at 2.00-2:45pm and will focus on our latest Big Question: Is knowledge dangerous? If you and your students would like to take part, simply register here. You can also join the Oxplore mailing list to receive updates on new Big Questions and upcoming events.

Any questions? Contact the Oxplore team.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

enrichment

independent learning

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By NACE team,

08 January 2020

|

Our summer term member meetup in Cardiff and autumn term meetup in Oxford both focused on curriculum enrichment for the more able – bringing NACE members together to share their schools’ approaches to extending and enriching provision within the classroom, across school and beyond.

For an overview of key ideas discussed at the events:

1. Maths masterclasses

At Chelmsford County High School, five off-timetable days are spread throughout the year, offering opportunities to participate in excursions and activities such as Model United Nations events, newspaper production and themed days. The programme incorporates subject-specific “masterclasses”, including a GCSE Maths Masterclass comprising a morning of off-site lectures, followed by an afternoon of tailored workshops.

This initiative gives all students the opportunity to extend their learning and experience new styles of teaching, says Jo Cross, Faculty Leader for Mathematics, Computing and Economics. She adds that it has been particularly effective in supporting highly able learners, with the bespoke workshops allowing for extension beyond the curriculum.

Top tips for implementation: “Positivity! Surprisingly, a day of maths is not everybody’s favourite activity… We balance this by segmenting the lectures with (maths-related) video clips and keeping the lectures relevant, to the point and easy to access for all, with differentiated questions in the workbooks.”

2. Peer mentoring

Sticking with maths, at Ormiston Sandwell Community Academy, a successful peer-to-peer maths mentoring programme is now being extended to other subject areas, including science and modern foreign languages. More Able Coordinator Alexia Binard says the scheme has challenged students to take ownership of their learning, stretching mentors to plan and deliver “lessons” to peers. She adds that participants on both sides have made good progress as a result, developing a range of additional skills alongside growing expertise in the area being covered.

Similarly, The Cotswold School’s Abigail Newby has been running a peer coaching scheme for several years, in which more able learners in Years 10 and 12 have the chance to academically coach a peer in Years 8 or 10 respectively. The impact on learners has been very positive, she says: “They report rises in confidence, ability to cope better in lessons, and the high ability pupils say it has deepened their own knowledge through having to explain something to a pupil who finds it difficult.”

Top tips for implementation: “Plan in advance how the scheme will be run. Decide which year groups will mentor others – for example, Year 10s mentoring Year 9s.” – Alexia Binard. “Have a dedicated venue, time and member of staff. Keep it distinct from more pastoral mentoring schemes (which we also have in school) – this is purely academic.” – Abigail Newby.

3. KS2-3 collaboration

Amy Clark, Assistant Headteacher at The Bromfords School and Sixth Form College, highlights collaboration between primary and secondary schools as key to extending learning and maintaining a high level of challenge throughout KS2-3 transition. Members of the school’s English and maths departments worked alongside primary school colleagues to plan and deliver a scheme of work which started in Year 6 and continued into Year 7, maintaining high expectations throughout. The initiative has resulted in higher standards and more effective provision on both sides, Amy says. “We were able to set students more quickly and efficiently, while Year 6 teachers were able to start to deliver skills needed for KS3.”

Top tips for implementation: “Get as many primary feeder schools involved as possible and plan ‘summer holiday’ work for learners at primary schools which don’t engage. Get other secondary schools in the catchment area involved.”

4. The Scholars Programme

Like a number of NACE members, Ysgol Gyfun Garth Olwg participates in The Brilliant Club’s Scholars Programme. Open to students from Years 5 to 12, the programme offers the opportunity to participate in a university-style scheme of learning, including small-group tutorials led by a PhD tutor, support to work on and submit an extended project, and events at partner universities.

“There is no doubt that the programme widens pupils’ horizons,” say the school’s Nia Griffiths and Carys Amos. “They visit two universities and participate in very challenging tutorials. They discuss subjects they wouldn’t have considered, and it promotes their oral skills while enhancing their vocabulary. It also raises aspirations, including for learners from disadvantaged backgrounds or whose parents didn’t go to university.”

Top tips for implementation: “Take care when scheduling. The scheme involves writing an extended assignment, which is quite time-consuming. It’s therefore best to avoid busy revision periods.”

5. Community Skills Week

At Pencoed Primary School, an annual Community Skills Week offers a range of enrichment activities linked to the world of work, delivered by parents, other family members and experts from the community. Deputy Headteacher Adam Raymond says the initiative has led to “improved knowledge and understanding of careers and the world of work, improved engagement and enjoyment of the curriculum as a whole, and the development of an ambitious attitude to lifelong learning.” In particular, he says, the scheme has supported more able learners’ development as “ambitious, capable learners”.

Top tips for implementation: “Align your community skills with your content curriculum offer. Delve into the expertise within your local community to support and extend the curriculum diet and ensure the logistical planning is tight – give as many different pupils as many different opportunities as possible.”

6. External speakers

The Hertfordshire and Essex High School runs a series of talks on areas outside of the curriculum, bringing in external speakers to give students access to a breadth of knowledge and experience. “Students are interested in attending the talks and it is easy for them to do so,” says Challenge Coordinator Peter Clayton. He adds, “Speakers will often come for free, which means it is manageable to run.”

Top tips for implementation: “Allowing students the change to discuss the talks afterwards might be beneficial. Perseverance in getting external speakers is worth it. Local universities will often help.”

7. Big Board Games Day

Last but not least, a special event originally run to raise money for the NSPCC has become an annual occurrence at St Francis RC Primary School. The school’s Big Board Games Day is a school-wide event, with more able learners assigned as board game “gurus” who move around the school teaching and playing games with pupils of all ages. They are also tasked with ensuring everyone has a group to play with.

MAT Coordinator David Boyd says the initiative has resulted in “improved self-esteem; improved organisational skills; developing thinking skills in a new way – to teach the game rather than just play it; developing social skills with peers and younger pupils; and a range of problem-solving skills in the games being played.”

Top tips for implementation: “Train ‘gurus’ beforehand (we do this in our weekly after-school Board Games Club). Set clear rules for all pupils to follow – no sore losers, no gloating, treat games and others with respect, and so on. Contact game publishers and distributors for donations to help start a school games collection.”

How does your school enrich the curriculum? Share your experience in the comments below, or get in touch to request additional information about the initiatives detailed above.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

collaboration

enrichment

transition

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Copthorne Primary School,

05 November 2019

|

Andrew Johnston, Teacher, Science Coordinator and Head of Research and Development at Copthorne Primary School, shares five approaches to develop resilience for all learners in your school…

The number of children under 11 being referred for specialist mental health treatment has increased by 50% and waiting times for such treatment have trebled (BBC freedom of information requests, July 2019). The Youth Association has recently called for mental health to be taught as part of the national curriculum. Furthermore, the Department of Education has said that early intervention is key to preventing mental health challenges later in life.

Clearly, there is a huge role for schools to play in supporting our young people to have good mental health. Unsurprisingly, there is also evidence that focusing on wellbeing is likely to impact positively on learning outcomes. The EEF has recently published recommendations for improving social and emotional learning (SEL) in schools – reporting that well-implemented SEL teaching has the potential to give learning gains of +4 months over a year.

What does this mean in the context of supporting our more able learners? Those with high achievement and/or potential can often be anxious about their academic performance. Students who are repeatedly told they are very able, and who find failure impossible to consider, often have problems associated with anxiety and self-worth. I would argue that these students need to be taught that failure and struggle are an essential element of learning and a normal part of life. As highlighted in Element 3c of the NACE Challenge Framework, it is important to consider “social and emotional support” as well as academic provision for the more able.

Many schools are already teaching ‘resilience’ and ‘wellbeing’: dogs in school, outdoor learning, mentoring and school-based therapy are some of the provisions being offered. As all schools will know, the new Ofsted framework places significant emphasis on curriculum: “Curriculum matters, as it defines the knowledge and experiences that learners will receive beyond their home environment.” With this in mind, it is important to consider whether we are teaching resilience and SEL as ‘add-ons’, or as integrated aspects of a broad curriculum.

Researcher and lecturer David Glynne-Percy highlights the importance of ensuring all learners have access to opportunities to develop resilience and self-esteem – particularly through extracurricular activities offered as part of the school day, so they are accessible to pupils who rarely stay after school. His research also highlights the benefits of opportunities to compete, develop competence and receive feedback – all helping to develop resilience, confidence, leadership and sustained engagement.

Serving an inner-city community, providing children with fresh experiences is one of the main drivers of our new curriculum. We have focused on enriching our curriculum in the following ways:

1. Working with the Brilliant Club to raise aspirations

We work with the Brilliant Club to raise the aspirations of our most able learners from families who have not yet had a university graduate. Supported by lecturers at Leeds and Manchester Universities, participating pupils can experience university lectures, complete academic assignments and get a taste of what it is like to continue their education at university and the opportunities this can afford them.

2. Wellbeing-focused school clubs

Our children have had the opportunity to develop their wellbeing through cooking, arts and crafts and sports clubs. Last year, as part of a programme focusing on essential life skills, we began a cycling club for pupil premium children and low prior-attainers – providing opportunities to develop fitness and balance, alongside the experience and challenge of mastering a new skill. As part of this, children were recently able to attend a UCI event in Bradford as part of the 2019 Cycling World Championships and represent our school there. We found these children developed an ambassadorial role and now encourage their peers to be involved. Children’s feedback shows that they feel valued members of the school and have further developed a sense of belonging. This year we will assess whether this impact leads to better engagement in other aspects of school life and improved academic outcomes.

3. Developing breaktime and lunchtime provision

As part of our curriculum development, breaktime and lunchtime provision was completely redeveloped last academic year. Staff, including mid-day meal supervisors, were trained to support children to play a range of games and activities during lunchtimes and playtimes. This resulted in a vast improvement in behaviour across the school during these periods, but also allowed children to develop their social and emotional skills as they received feedback and instruction from staff.

4. Incorporating growth mindset

Consider this list summarising the behaviour of individuals with fixed mindsets:

· Overgeneralising from one experience (e.g. a single test)

· Exaggerating failures relative to successes

· Categorising themselves in unflattering ways

· Setting self-worth contingencies e.g. “If I do not get the highest mark in the class in my maths test I am a failure (or will be in trouble with my dad).”

· Losing faith in ability to perform tasks

· Underestimating the efficacy of effort

As a school we saw that these statements described some of our highest-achieving pupils.

Over the last three years, we have introduced growth mindset across the school, aiming to encourage children to enjoy challenges, embrace mistakes and understand that risk-taking is an important part of their learning. After initial training, teaching staff have completed cycles of lesson study to assess the impact of this approach. We have found that all groups of children are more open to trying difficult tasks or new skills and fewer children have a fear of failure or appearing less intelligent if they make mistakes.

Further to this, we asked staff to follow this guidance for supporting learners, including the more able:

1. Tell them ability is not fixed.

2. Encourage risk-taking in lessons.

3. Refuse to help students who have not attempted tasks.

4. Highlight failure as part of learning and praise effort.

5. Down-play success but praise effort.

5. Appointment of a Mindfulness and Wellbeing Champion

The appointment of a Mindfulness and Wellbeing Champion in 2017 has helped raise the profile of mental health and wellbeing across the school and our multi-academy trust for both staff and learners. This staff member has developed a range of strategies to teach resilience and mindfulness – taking risks, celebrating mistakes, open-ended tasks, mastery-style teaching – and has worked with parents to help them to understand the impact of self-esteem on their child’s success at school.

Read next: 4 ways to avoid “But am I right Miss?”

Tags:

aspirations

enrichment

mindset

research

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Matthew Williams,

15 April 2019

Updated: 07 August 2019

|

What are Oxbridge admissions tutors really trying to assess during the famously gruelling interview process? Dr Matt Williams, Access Fellow at Jesus College Oxford, shares “four Cs” used to gauge candidates’ suitability for a much sought-after place.

Oxbridge interviews have taken on near-mythic status as painful reckonings. The way they are sometimes described, a trial by ordeal sounds more appealing.

I used to think as much, before I became an interviewer at Oxford. I’ve worked on politics admissions for several colleges for years now. And “work” truly is the verb here. Admissions tutors and officers at Oxford and Cambridge work very hard over months to ensure they choose the best applicants, and do so fairly. It’s honestly heartening to see how committed tutors are.

It is not even remotely in our interests to put candidates under emotional strain. So a mythic sense of interviews as tests of psychological resilience is nonsense. At Oxford and Cambridge we invite prospective students to come and stay in our colleges, eat in our dining halls and chat with our students and staff. As you’d hope from any professional job interview, the process is friendly, transparent and focused on encouraging the best performances from candidates. Below I’ve outlined a few concrete ideas as to what we are looking for, and how students can prepare.

In the interviews we tend to scribble down notes as the candidate is talking. But what exactly are we recording? What makes for good, mediocre and bad performances at interview? I record lots of data during interviews, which can be collated under four Cs. These help us gauge, accurately, a candidate’s academic ability and potential. This ultimately, is all we are testing at interview…

1. Communication

Candidates do not need to be self-confident and comfortable in expressing their ideas. Our successful candidates are mostly just normal people, with the sort of self-effacing humility you’d expect from a randomly selected stranger. As such, candidates should not be put off by cock-of-the-walk types who seem instantly at ease in our ancient surroundings.

We are not judging candidates by their ease of manner, but we do judge candidates by their ability to communicate. Meaning that candidates need to be able and willing to share their thinking as clearly as possible. Even if a candidate nervously glances at the floor and speaks softly, provided they answer our questions and help us understand their views they will be performing well.

More specifically, we are seeking answers to the questions we pose. There may not be a single answer, but it is not terribly helpful if students try to wriggle out of responding to us. As an example, the following question doesn’t have one correct (or even any correct) response:

“Can animals be said to have rights?”

Candidates need to avoid the temptation of saying either that the question is unanswerable, or sitting on the fence. Such responses are, to be blunt, intellectually lazy. We commonly have candidates “challenging the terms of the question” and thereby not answering the question at all. That is easy. Anyone can do that. Far harder is sticking your neck out and offering a solution, however tentative, to a very complex puzzle.

That said, we’re not expecting candidates to alight on their preferred solution immediately. So candidates should “show their working” and talk through their ideas as they coalesce into a solution. They can challenge aspects of the question and enquire about the wording. It may take the whole interview to come up with an answer, but at least an answer of sorts is being proposed.

2. Critical thinking

The question as to whether animals have rights is contestable. We will challenge any answer a candidate offers to see how they can defend their position. We are not expecting the candidate to drop their resolve and agree with us, but nor should they cohere rigidly to their position if it is clearly flawed. The important point is that candidates are open-minded to the possibility of other, perhaps better, solutions to the puzzle at hand, and a willingness to critique their own thinking.

Often candidates feel that they have done badly when they face critical questioning. Far from it. This is normal and reflects the fact that they have answered the question and given us (the interviewers) something to explore further.

3 and 4. Coherence and Creativity in argumentation

When posing critical questions we may encourage the candidate to identify incoherences in their case. Let’s say they argue that dogs have rights, but racing hounds do not. This could be a category error and we might ask whether they meant to say that all dogs except racing hounds have rights, or if they have made a critical misstep in the case.

Again, having a point of incoherence identified is not a bad sign. What matters is how the candidate responds. If they fail to recognise or resolve a true incoherence, that could suggest an inability to self-critically evaluate an argument.

Creativity, meanwhile, is something of an X-factor. We’re not expecting utterly original thinking in response to our intractable intellectual puzzles. But we do appreciate a willingness not to simply parrot ideas from A-level, or from the press. We appreciate a nascent (but not fully formed) capacity in a candidate to stand on their own intellectual feet.

This is where candidates can (but don’t have to) draw on wider reading or other academic experiences they have had. A lot of candidates are keen to show off what they know, but we’re testing how they think. So, we don’t want long quotes from highfalutin sources, per se; we want the candidates to come up with their own ideas, even if those ideas are half-formed and tentatively expressed.

The bottom line is that we are not looking for perfection, or else there would be little point in seeking to educate the candidates. We’re looking for potential, and it is often raw potential. Therefore willingness, motivation and enthusiasm all play a big part in the four Cs as well.

Tags:

access

aspirations

CEIAG

creativity

critical thinking

higher education

myths and misconceptions

Oxbridge

Oxford

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Natasha Goodfellow,

14 February 2019

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

Oracy skills underpin all areas of learning and life – and they certainly shouldn’t be taught only to those who join the school debating club, argues Natasha Goodfellow of the English-Speaking Union. Build oracy into every lesson with these five simple activities – suitable for all learners, phases and subjects.

Think about what you’ve done today. How much time have you spent talking, explaining, listening to deduce meaning or ease conflict? How much time have you spent persuading people to your point of view, or to do something you want doing, versus writing essays or doing maths?

Most communication is verbal, rather than written. And yet oracy receives much less attention in the school curriculum than literacy and numeracy. Even in schools which pride themselves on their oracy results, too often the teaching happens in debate or public speaking clubs as opposed to lesson time.

Why make oracy part of every lesson?

While a lunchtime or after-school club can be a good place to start, participants will generally be self-selecting, precluding many of those who might benefit the most. It’s far better to introduce an oracy element into every lesson.

As good teachers know, oracy is about far more than speaking and listening alone. Oracy activities encourage learners to voice and defend their opinions, to think for themselves and to listen critically. And, perhaps most importantly, they build confidence and resilience. However able an individual may be, it’s one thing to argue a point in an essay; it’s quite another to do that in person, in front of an audience, with others picking holes in your arguments, questioning your thought processes or your conclusions. And it’s another leap again to review the feedback and adjust your opinion or calmly concede that you may have been wrong.

With regular practice, what might initially seem uncomfortable or impossible is soon recognised as simply another skill to be learnt. Happily, it’s all part of a virtuous circle – the better learners are at speaking, the better their written work will be. The firmer their grip on the facts, the more convincing their arguments. And, ultimately, the more they are challenged and asked to think for themselves, the more rewarding their education will be.

Here are five simple oracy activities to incorporate in your daily teaching:

1. Balloon debate

Display a range of themed prompts on the board. For instance, in chemistry or physics you might choose different inventors; in PSHE you might choose “protein”, “fat” and “sugar”. Ask the class to imagine they are in a balloon which is rapidly sinking and that one person or item must be thrown out of the balloon. Each learner should choose a prompt and prepare a short speech explaining why he/she/it deserves to stay in the balloon. For each of the items listed, choose one learner to take part in the debate. The rest of the class should vote for the winners/losers.

2. Draw a line

This activity works well for lessons that synthesise knowledge. For example, you may use it to recap a scheme of work. Draw a line on the board. Label it “best to worst”, “most certain to least certain”, or whatever is appropriate. Learners should copy this line so they have their own personal (or small group) version. Introduce items – for example, in geography, different sources of energy; in history, difference sources of evidence. As you discuss each item and recap its main features, learners should place the item on their own personal line. In small groups or as a class, learners can then discuss any disagreements before placing the item on the collective class line on the board.

3. Where do you stand?

Assign one end of the room “agree” and the other “disagree”. When you give a statement, learners should move to the relevant side of the room depending on whether they agree or disagree. Using quick-fire, true/false questions allows you to swiftly assess understanding of lesson content, while more open questions allow learners to explain and defend their thinking.

4. Talking bursts

At appropriate points in a lesson, ask individual learners to speak for 30 seconds on a theme connected to the subject in hand. This could be in a colloquial mode – an executioner arguing that hanging should not be banned, for example; or a more formal mode – such as a summary of the history of capital punishment. Begin with your more able learners as a model; soon the whole class will be used to this approach.

5. Praise and feedback

Finally, make time for praise and feedback – both during oracy activities and as part of general class discussions. Invite comments on how speeches could be improved in future, and recognise and celebrate learners when they make good arguments or use appropriate vocabulary.

Natasha Goodfellow is Consultant Editor at the English-Speaking Union where she oversees the publication of the charity’s magazine, Dialogue, and content on its website. She has worked as an English teacher abroad and is now a writer and editor whose work has appeared in The Sunday Times, The Independent and The Week Junior.

NACE is proud to partner with the English-Speaking Union (ESU), an educational charity working to ensure young people have the speaking and listening skills and cultural understanding they need to thrive. The ESU’s Discover Debating programme, a sustainable programme designed to improve listening and speaking skills and self-confidence in Years 5 and 6, is now open for applications, with large subsidies available for schools with high levels of FSM and EAL. To find out more and get involved, visit www.esu.org/discover-debating

Read more:

Plus: for more oracy-based challenges to use in your classroom, watch our webinar on this topic (member login required).

Not yet a NACE member? Find out more, and join our mailing list for free updates and free sample resources.

Tags:

aspirations

critical thinking

enrichment

feedback

oracy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Gemma Quinn,

12 February 2019

Updated: 23 December 2020

|

In December 2018, Chesterfield High School was accredited with the NACE Challenge Award, in recognition of school-wide high-quality provision for more able learners within a context of challenge for all. Gemma Quinn, Director of Learning for MFL and Challenge Lead, explains why the school decided to focus on raising aspirations, and key steps taken in achieving this.

At Chesterfield High School, our students and staff have wholeheartedly benefited from using the NACE Challenge Framework and from NACE visits to school. We fully understand that the majority of a learner’s time in school is spent in the classroom, and therefore it is essential that our provision provides all learners with opportunities for challenge.

However, we identified an area beyond the classroom as a key area for development. We wanted to ensure learners go outside their comfort zone, build resilience and take intellectual risks to fully prepare them for life after school. We carried out pupil voice, analysed our data, and we determined that not only did we want students to be inspired to learn in school, but we also wanted to raise aspirations to enable greater transition into the sixth form and beyond.

Using the six key elements of the NACE Challenge Framework, we identified three areas – curriculum, teaching and support; communication and partnership; and monitoring and evaluation – as key to developing our provision for, and raising the aspirations of, our learners.

For other schools seeking to raise aspirations, we would recommend the following steps:

1. Listen to learners

We collected pupil voice through anonymous questionnaires and pupil interviews. This highlighted some great strengths, such as our ability to listen and take account of the views of our more able learners within a wider context and our ability to increase parental responsibility in supporting their child’s learning outside of school.

We are passionate about celebrating all learners’ achievements and strengths in an environment where both staff and learners have high expectations of themselves and of one another. However, by listening to learner feedback we recognised that we needed to provide our learners with greater opportunities to experience the world beyond the classroom to support further success.

2. Embed a whole-school approach

We set actions in place to develop our curriculum to offer breadth, depth and flexibility. We increased our enrichment resources and wider learning opportunities for all, with a focus on raising the aspirations of our learners.

In working towards the NACE Challenge Award, our fundamental aim was to ensure that the school’s vision and ethos are at the heart of everything that happens – to ensure “for everyone the best”. To ensure this was implemented across the school, we identified a Challenge Lead Representative. It was envisaged that the Challenge initiative would strengthen the school community’s drive to promote, actively witness and celebrate the progress and achievement of more able learners. As a result, highly able pupils (HAPs) will be motivated to succeed and to participate in all learning opportunities that will positively nurture their academic and personal growth.

3. Involve staff at faculty level

We also identified a HAP Representative in each faculty area, who reported to the whole-school Challenge Lead Representative. The key objectives of the HAP Representatives are to ensure that the achievement and progress of HAPs are consistently monitored and celebrated within their faculty area. Representatives also help to develop their faculty’s approach to HAP teaching and learning in line with whole-school teaching and learning initiatives, thus leading to improved progress and attainment.

We created a subject attributes document which included three key strands for each individual subject area. These included characteristics of a HAP, activities that HAPs should do, and how parents can support HAPs.*

4. Provide inspiring examples and role models

We invited an ex-student who is now studying at Cambridge University into school. She was able to give staff a greater understanding of her school experience and how we guided and prepared her for university life. Through discussions, she inspired current learners to think beyond their original choices and to aim for Russell Group universities and Oxbridge. She was also open to keeping in touch with students to mentor and address any questions they had.

In addition, we allocated learners with an aspirations mentor who was able to advise them on the application process and subject choices at A-level to maximise their chances of getting a university place. Learners also took part in mock interviews with volunteers in the community in their chosen field of work or study, which increased their confidence and helped to develop their oracy skills.

Visits out to universities, including trips to open days’ and residential trips were promoted through our Challenge Lead Representative. Students visited universities around the country and applied for the prestigious Cambridge Shadowing Scheme.

We are proud…

Using the Challenge Framework helped us to identify our strengths and areas for development in more able provision. Through the action plan created as part of our work with the framework, we highlighted actions and the intended impact of these on target groups of learners. We are extremely proud of the steps we have taken to ensure our more able provision allows all our learners to have the best possible life chances.

Gemma Quinn is the Director of Learning for MFL and the Challenge Lead at Chesterfield High School. She is an experienced teacher of French and Spanish to KS5 and a skilled coach and mentor. Gemma enjoys working with various subject leaders across the school to improve learner outcomes and looks forward to continuing to support them in the future.

*To view Chesterfield High School's HAPs subject attributes document, log in to our members' resource library and go to the "Identification & transition" section.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

enrichment

higher education

partnerships

student voice

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Beth Hawkins,

08 February 2019

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

Do the young people in your school feel confident engaging with scientific concepts, terminology, experiences and thinking? Do they believe science is “for them”? In this blog post, Science Museum Group (SMG) Academy Manager Beth Hawkins shares five ways teachers can help learners develop “science capital” – promoting more positive perceptions of, attitudes towards and aspirations within the sciences.

To read more about the research behind these recommendations, click here.

1. Personalise and localise your content

The more we can relate science content to what matters in learners’ lives and local communities, the more we can create “light bulb moments” where they can see the personal relevance and feel closer to the topic. This is more than contextualising science through world events or generic examples; it is about taking some time to find out about the current interests and hobbies of the individual learners in your classroom. This might include discussing how forces link to a local fair or a football match, or how understanding the properties of materials or chemical reactions can help when baking or cooking at home.

2. Show how many doors science can open

Many young people see science as a subject that only leads to jobs “doing science” – working alone in a laboratory or in a medical field. Yet from fashion and beauty to sports and entertainment, business or the military, nearly all industries use science knowledge and skills. Demonstrate that science can open doors to any future career, to help young people see the value and benefit of science to their future.

For ideas and guidance on linking learning to the world of work, log in to the NACE members’ site for the NACE Essentials guide to CEIAG for more able learners.

3. Widen perceptions about who does science

Science seems to have a bit of an image problem. If you search online for images of scientists, your screen will be filled with hundreds of images of weird-looking men with wild hair, wearing white lab coats and holding test tubes or something similar. Scientists are often portrayed similarly in the popular culture that children are exposed to every day – it is no wonder many young people find it hard to relate. Take every opportunity to show the diversity of people who use science in their work or daily lives so that learners can see “people like me” are involved in science and it isn’t such an exclusive (or eccentric) pursuit.

4. Maximise experiences across the whole learning landscape

Young people experience and learn science in many different places – at school, at home and in their everyday life. No single place or experience can build a person’s science capital, but by connecting or extending learning experiences across these different spaces, we can broaden learners’ ideas about what science is and open their eyes to the wonders of STEM. Link out-of-school visits and activities back to content covered in the classroom. You could also set small related challenges or questions for learners to investigate at home or in their local area.

5. Engage families and communities

Our research has found that many families see science as simply a subject learned in school, not recognising where and how it relates to skills and knowledge they use every day. All too often we hear parents saying, “I am not a science-y person”, “I was terrible at science in school” or even “You must be such a boffin if you are good at science.” When young people hear those close to them saying such things, it is not surprising that a negative perception of science can start to grow and the feeling “this is not for me” set in.

Encourage learners to pursue science-related activities that involve members of their family at home or in their local community. Model and encourage discussions which link science to young people’s interests – this will help to show the relevance of science and normalise it. For specific ideas, check out The Science Museum’s free learning resources.

Additional reading and resources:

Beth Hawkins is the Science Museum Group (SMG) Academy Manager. She has been working in formal and informal science education for over 22 years, including roles as head of science in two London schools. Since joining the Science Museum, she has developed and delivered training to teachers and STEM professionals nationally and internationally, and led many of the SMG’s learning research to practice projects. The Science Museum Group Academy offers inspirational research-informed science engagement training and resources for teachers, museum and STEM professionals, and others involved in STEM communication and learning.

Tags:

access

aspirations

free resources

science

STEM

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Beth Hawkins,

08 February 2019

Updated: 08 April 2019

|

You’ve probably heard of cultural capital, but what about science capital? In this blog post, Science Museum Group (SMG) Academy Manager Beth Hawkins outlines recent research on young people’s engagement with and attitudes to science – and how understanding this can help schools increase take-up of STEM education and career paths.

At the Science Museum, engaging people from all backgrounds with science, engineering, technology and maths is at the heart of what we do. Over the past six years, we’ve been working with academic researchers on a project called Enterprising Science, using the concept of science capital to better understand how young people from all backgrounds engage with science and how engagement can be increased through different science-related experiences.

Recent research conducted by University College London with over 40,000 young people across the UK found that while many find science interesting, few are choosing to study science post-16, or consider pursuing a career in science. This is because they struggle to see that science is “for them” or relevant to their lives.

Why should we care?

In one way or another, science is continually changing and improving the way we live. It makes and sustains our society and will help us understand and solve the big questions our world faces. It is a creative and imaginative human endeavour, a way of thinking, asking questions and observing the world around us.

As such, science can open doors and can be invaluable in almost any job, across any sector. It is predicted that by 2030 the UK will have over 7 million jobs that need STEM skills, and it has been recognised that science can help broaden young people’s life choices and opportunities by keeping their future options open, especially among lower socioeconomic groups.

What is “science capital”?

Science capital is a measure of your attitude to and relationship with science. It is not just about how much science you “know”; it also considers how much you value science and whether you feel it is “for you” and connected to your life.

Imagine a bag or holdall that carries all the science-related experiences you have had. This includes what you have learned about science; all the different STEM-related activities you have done, such as watching science TV programmes or visiting science museums; all the people you know who use and talk about science; and whether science is something you enjoy and feel confident about.

How can science capital research be used?

At the Science Museum, we’ve been using science capital research to reflect on how we develop and shape our learning programmes and resources for schools and families. The research also underpins the training we deliver for teacher and science professionals through our new Academy.

For schools, the researchers have developed a science capital teaching approach that can be used with any curriculum.

The research suggests a science capital-informed approach can have the following benefits for learners:

- Improved understanding and recall of science content

- Recognising the personal relevance, value and meaning of STEM

- A deeper appreciation of science

- Increased interest in/pursuit of STEM subjects and careers post-16

- Improved behaviour

- Increased participation in out-of-school science activities

Ready to get started? Discover five ways to help young people develop science capital.

Additional reading and resources:

Beth Hawkins is the Science Museum Group (SMG) Academy Manager. She has been working in formal and informal science education for over 22 years, including roles as head of science in two London schools. Since joining the Science Museum, she has developed and delivered training to teachers and STEM professionals nationally and internationally, and led many of the SMG’s learning research to practice projects. The Science Museum Group Academy offers inspirational research-informed science engagement training and resources for teachers, museum and STEM professionals, and others involved in STEM communication and learning.

Tags:

access

aspirations

free resources

research

science

STEM

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elaine Ricks-Neal,

04 February 2019

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

“Character” may be the latest buzzword in education – but it’s long been at the core of the NACE Challenge Framework, as NACE Challenge Award Adviser Elaine Ricks-Neal explains…

Increasingly schools are focusing on the development of “character” and learning dispositions as performance outcomes. Ofsted is also making it clear that it will look more at how well schools are developing resilient, well-rounded, confident young learners who will flourish in society.

The best schools, irrespective of setting, have always known the importance of this. And this focus on character has long been at the heart of the NACE Challenge Framework – a tool for school self-review and improvement which focuses on provision for more able learners, as part of a wider programme of sustainable school improvement and challenge for all.

Here are 10 key ways in which the Framework supports the development of school-wide approaches, mindsets and skills for effective character education:

1. “Can-do” culture

The NACE Challenge Framework embeds a school-wide “You can do it” culture of high expectations for all learners, engendering confidence and self-belief – prerequisites for learning.

2. Raising aspirations

The Framework challenges schools to raise aspirations for what all learners could achieve in life, irrespective of background. This is especially significant in schools where learners may not be exposed to high levels of ambition among parents/carers.

3. Curriculum of opportunity

Alongside a rich curriculum offer, the Framework asks schools to consider their enrichment and extracurricular programmes – ensuring that all learners have opportunities to develop a wide range of abilities, talents and skills, to develop cultural capital, and to access the best that has been thought and said.

4. Challenge for all

At the heart of the Framework is the goal of teachers understanding the learning needs of all pupils, including the most able; planning demanding, motivating work; and ensuring that all learners have planned opportunities to take risks and experience the challenge of going beyond their capabilities.

5. Aspirational targets

To ensure all learners are stretched and challenged, the Framework promotes the setting of highly aspirational targets for the most able, based on their starting points.

6. Developing young leaders

As part of its focus on nurturing student voice and independent learning skills, the Framework seeks to ensure that more able learners have opportunities to take on leadership roles and to make a positive contribution to the school and community.

7. Ownership of learning

The Framework encourages able learners to articulate their views on their learning experience in a mature and responsible way, and to manage and take ownership of their learning development.

8. Removing barriers

The Framework has a significant focus on underachievement and on targeting vulnerable groups of learners, setting out criteria for the identification of those who may have the potential to shine but have barriers in the way which need to be recognised and addressed individually.

9. Mentoring and support

Founded on the belief that more able and exceptionally able learners are as much in need of targeted support as any other group, the Framework demands that schools recognise and respond to their social and emotional and learning needs in a planned programme of mentoring and support.

10. Developing intrinsic motivation

Beyond recognising individual talents, the Framework promotes the celebration of success and hard work, ensuring that learners feel valued and supported to develop intrinsic motivation and the desire to be “the best they can.”

Find out more… To find out more about the NACE Challenge Development Programme and how it could support your school, click here or get in touch.

Tags:

aspirations

character

disadvantage

enrichment

mentoring

mindset

motivation

resilience

school improvement

student voice

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|