Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

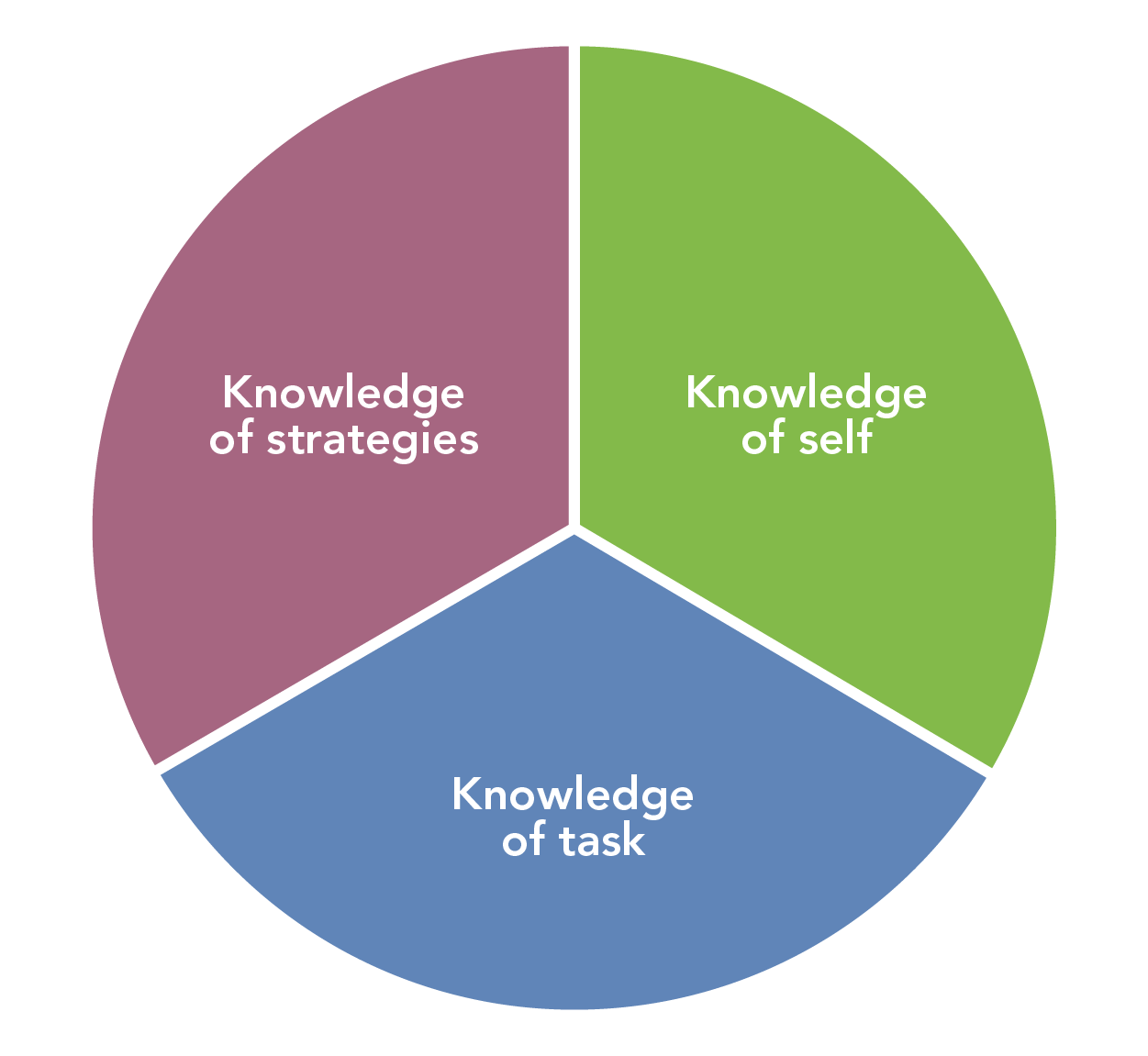

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Hilary Lowe,

08 November 2021

|

NACE Research and Development Director Hilary Lowe explores the relationship between language and learning, and the development of language-rich learning environments as a key factor in cognitively challenging learning experiences.

“We use language to define our world, while at the same time the social world in which we live defines our language. The structure of language and the variation we find within it depend both on the social world as well as the ways in which we create an identity for ourselves and the ways in which we build relations with others. Understanding how language both constrains our thoughts and actions and how we use language to overcome those constraints are important lessons for all educators.” (Silver & Lewin, 2013)

We are sometimes so busy talking in classrooms that we forget about the centrality of language for learning. It is for this reason that this blog post focuses on what is arguably a neglected area in the training of teachers: an understanding of the primacy of language in the learning process, of the link between language and higher-level cognition and high achievement, and the critical role of teachers in developing high-level language skills at all stages of schooling.

The development of language and literacy has long been a tenet of the National Curriculum as well as a significant area of research. Research such as that from Oxford Children’s Language (Oxford, 2018; 2020) has continued to emphasise the importance of linguistic wealth, and the link between paucity of language and academic failure and diminished life chances.

The notion of ‘oracy’ has been less visible in policy developments but has received more recent attention through, for example, the survey undertaken by the Centre for Education and Youth and Oxford University (2021) and the Oracy APPG Speak for Change Inquiry report (April, 2021). The APPG inquiry found that the development of spoken language skills requires purposeful and intentional teaching and learning throughout children’s schooling. It also found that there is a concerning variation in the time and attention afforded to oracy across schools, meaning that for many children the opportunity to develop these skills is left to chance. The inquiry concluded that there is an indisputable case for oracy as an integral aspect of education. The conclusions also emphasised the primordial place of oracy for young people and the critical role of employers, teachers and Ofsted in trying to ensure that these skills are developed to a high level.

In the first phase of NACE’s research initiative Making Space for Able Learners, which focuses on cognitive challenging learning, we were delighted to find examples of effective practices in language development and use, which led us to a renewed interest in the significance of language and discourse in high achievement. The schools in the project which demonstrated consistently excellent practice and high achievement for their most able learners had a systematic and systemic approach to the development and use of high-level language skills alongside wider literacy and oracy development (see below for examples). Some background: language, thinking and learning

The interaction between thought and language has long been the subject of research and academic debate. The thesis that natural language is involved in human thinking is universally well supported, although research into language and cognition often makes reference to ‘strong and weak theories’ of this thesis. Research suggests that higher-level language processes hold a pivotal role in higher-order executive and cognitive activities such as inference and comprehension, and indeed wider expressive communication skills.

Vygotsky (1978) writes that "[…] children solve practical tasks with the help of their speech, as well as their eyes and hands" (p. 26). In Vygotsky's view, speech is an extension of intelligence and thought, a way to interact with one's environment beyond physical limitations: “[…] the most significant moment in the course of intellectual development, which gives birth to the purely human forms of practical and abstract intelligence, occurs when speech and practical activity, two previously completely independent lines of development, converge.” (p. 24).

This higher level of development enables children to transcend the immediate, to test abstract actions before they are employed. This permits them to consider the consequences of actions before performing them. But most of all, language serves as a means of social interaction between people, allowing "the basis of a new and superior form of activity in children, distinguishing them from animals" (p. 28f). Vygotsky wrote, "human learning presupposes a specific social nature and a process by which children grow into the intellectual life of those around them" (p. 88). Language acts both as a vehicle for educational development and as an indispensable tool for understanding and knowledge acquisition.

In the classroom, therefore, we need to attend to the development of higher-level language processes as explicitly as we do to substantive subject skills and knowledge.

The functions of language in education

The various functions of language most pertinent in the classroom include:

- Expression: ability to formulate ideas orally and in writing in a meaningful and grammatically correct manner.

- Comprehension: ability to understand the meaning of words and ideas.

- Vocabulary: lexical knowledge.

- Naming: ability to name objects, people or events.

- Fluency: ability to produce fast and effective linguistic content.

- Discrimination: ability to recognize, distinguish and interpret language-related content.

- Repetition: ability to produce the same sounds one hears.

- Writing: ability to transform ideas into symbols, characters and images.

- Reading: ability to interpret symbols, characters and images and transform them into speech.

(Lecours, 1998).

All of these functions are key components in the teaching and learning process. Teachers and students use spoken and written language to communicate with each other formally and informally. Students use language to comprehend, to question and interrogate, to present tasks and learning acquired – to display knowledge and skills. Teachers use language to explain, illustrate and model, to assess and evaluate learning. Both use language to develop relationships, knowledge of others and of self. But language is not just a medium for communication – it is intricately bound up with the nature of knowledge and thought itself.

What does this mean for cognitively challenging learning?

For the development of high levels of cognition and to achieve highly, pupils need to develop the language associated with higher-order thinking skills in all areas of the curriculum, such as hypothesising, evaluating, inferring, generalising, predicting or classifying (Gibbons, 1991).

In an educational context it is through iterations of linguistic interactions between teacher and student – and peer to peer – that the process of advancing in learning and knowledge occurs. As Hodge (1993) notes, with limited time in the classroom, teachers often spend much of the available time conveying information rather than ensuring comprehension. This reduces the opportunities for a range of linguistic interactions and for learners to acquire and practise the higher-level language skills associated with high achievement. Planning and organising teaching and learning therefore needs to allow for an increase in opportunities for rich language environments and interactions alongside a cognitively challenging curriculum.

In the NACE research project school visits, we witnessed numerous incidences of highly effective and consistent practices in classroom discourse which clearly contributed to the achievement of highly able learners. These included:

- Teachers modelling advanced language and skilled explanation and questioning;

- Pupils being taught the language of skills such as reasoning, synthesis, evaluation;

- Frequent use of ‘dialogic’ frameworks and enquiry-based learning;

- The use of disciplinary discourse and higher tiers of language;

- Instructional models which include and prioritise the above.

Examples of effective, language-rich learning environments from the project include:

- Portswood Primary School: focus on the early development of vocabulary, language and talk. Teachers use sophisticated language to communicate expectations and learning.

- Alfreton Nursery School: teaching develops skills of concentration, as pupils focus on a central stimulus/object and formulate “big questions”. There is also an explicit focus on team working with reference to reasons “why we can agree to disagree” and the importance of listening. The teacher follows these pupil-led ideas in later sessions.

- Glyncoed Primary School: a challenging curriculum is achieved through planning and delivery of problem solving-based activities, extended and cognitively demanding tasks, and pupil choice. Teacher talk and high-level and qualitatively differentiated questioning, rich dialogue and cognitive talk is in evidence. Excellent modelling and explanations are also pervasive.

- Greenbank High School: pupils are stimulated by differentiated questions prompting them to test hypotheses, make predictions and transfer their knowledge to new contexts. As a result, pupils are working at a strong, sustained pace.

You can read more about the project and order copies of the report here.

Improving the quality and nature of linguistic interaction and discourse within the classroom can better equip learners to engage in cognitive challenge. Learners thus equipped can also move more effectively from guided practice to independence and self-regulation. Teachers working with more able pupils must have a clear pedagogical strategy in mind, with discourse and well-planned questioning an integral part of that strategy. By using a highly interactive pedagogical model, which is language-dependent, teachers get rapid feedback about how well knowledge schemas are forming and how fluent pupils have become in retrieving and using what they have learnt. Working with the most able learners, the quality of questioning and questioning routines must provide the teacher with diagnostic information and the pupils with increased challenge.

Creating language-rich schools and classrooms: implications for teacher development

The development of language is too important to be left to be ‘caught’ alongside the rest of the taught curriculum. We need to give it explicit attention across the curriculum, alongside subject knowledge and skills. To do this expertly teachers should have access to professional development opportunities which give them insights into substantive areas of language acquisition and development – including what that means at different ages and stages and for learners of different abilities and language experience.

NACE’s future CPD and resources will therefore focus on issues in and strategies for language development for high achievement, including:

- Case studies of NACE evidence schools with excellent practice in language for high achievement;

- The language needs and characteristics of different learners, including the most able;

- Creating language-rich school environments;

- Approaches to teaching and learning for language development;

- EAL learners;

- Developing a whole-school language policy.

Schools accredited with the NACE Challenge Award are invited to join our free termly Challenge Award Schools Network Group events (online) to share effective practice in this and other areas. View upcoming events here, or contact communications@nace.co.uk to learn more about NACE’s work in this field and/or to share your school’s experience.

References

- Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group, Speak for Change, oracy.inparliament.uk, 2021

- Centre for Education and Youth with Oxford University Press, Oracy after the Pandemic, cfey.org, 2021

- Gibbons, P., Learning to Learn in a Second Language, Primary English Teaching Association, 1991

- Hillman, D. C. A., https://www.quahog.org/thesis/role.html, 1997

- Hodge, B., Teaching as Communication, Routledge, 1993

- Hodge, G. I. V. and Kress, G. R., Language as Ideology, Routledge, 1999

- Lecours, A. R. et al, Literacy and The Brain in The Alphabet and The Brain, Springer-Verlag, 1988

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A., Making Space for Able Learners, NACE, 2020

- Oxford Language Report, Why Closing the Language Gap Matters, OUP, 2018

- Oxford Language Report, Bridging the Word Gap at Transition, OUP, 2020

- Silver, R. E. and Lewin, S. M., Language in Education: Social Implications, Bloomsbury, 2013

- Vygotsky, L. S., Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, London: Harvard University Press, 1978

Tags:

cognitive challenge

CPD

language

oracy

research

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 October 2021

|

NACE Research & Development Director Dr Ann McCarthy shares key principles for effective assessment planning and practice, within cognitively challenging learning environments.

Following two academic years of uncertainty and alternative arrangements for teaching and assessment, the conversation regarding testing and assessment has become increasingly important. Upon return to the routines of day-to-day classroom teaching, schools have had to find ways to assess knowledge, progress and understanding achieved through distance learning or redesigned classroom practices. For older pupils there has been a need to provide evidence to examination boards to secure grades and guarantee appropriate progression routes. This inherent need to provide checks and balances before pupils’ achievement is recognised can become a distraction from the art of teaching. In fact, Rimfield et al (2019) found a very high agreement between teacher assessments and exam grades in English, maths, and science.

- Could we examine less often and use classroom-based assessment more often?

- Should we rethink testing and assessment and their position in the learning process?

Testing vs assessment

The terms test and assessment are often used interchangeably, but in the context of education we need to recognise the difference. A test is a product which is not open to interpretation; it uses learning objectives and measures success achieved against these. Teachers use tests to measure what someone knows or has learned. These may be high-stakes or low-stakes events. High-stakes tests may lead to a qualification, grading or grouping, whereas low-stakes tests can support cognition and learning. Testing takes time away from the process of learning and as such testing should be used sparingly, when necessary and when it contributes significantly to the next steps in teaching or learning.

Assessment, by contrast, is a systematic procedure which draws on a range of activities or evidence sources which can then be interpreted. Regardless of the position teachers hold regarding the use of testing and examinations, meaningful assessment remains an essential part of teaching and learning. Assessment sits within curriculum and pedagogy, beginning with diagnostic assessment to plan learning which best reflects the needs of the learner. A range of formative assessment activities enable the teacher and pupils to understand progress, improve learning and adapt the learning to reflect current needs. Endpoint activities can be used as summative assessments to appreciate the degree to which knowledge has been acquired, alongside varied and complex ways in which that knowledge can be used.

Assessment might be viewed in three different ways: assessment of learning; assessment for learning; and assessment as learning. The choice of assessment practice will then impact on its use and purpose. Regardless of the process chosen and the procedures used, the teacher must remember that the value of the assessment is in the impact it has on pedagogy and practice and the resulting success for the pupils, rather than as an evidence base for the organisation.

NACE research has shown that cognitively challenging experiences – approaches to curriculum and pedagogy that optimise the engagement, learning and achievement of very able young people – will have a significant and positive impact on learning and development. But how can we see this working, and what role does assessment play? When planning for cognitively challenging learning, assessment planning should reflect the priorities for all other aspects of learning.

A strategic approach to assessment which supports cognitively challenging learning environments

When considering the place of assessment in education, teachers must be clear about:

- What they are trying to assess;

- How they plan to assess;

- Who the assessment is for;

- What evidence will become available;

- How the evidence can be interpreted;

- How the information can then be used by the teacher and the pupil;

- The impact the information has on the planned teaching and learning;

- The contribution assessment makes to cognition, learning and development.

Effective assessment is integral to the provision of cognitively challenging learning experiences. With careful and intentional planning, we can assess cognitive challenge and its impact, not only for the more able pupils, but for all pupils. Assessments are used to measure the starting point, the learning progression, and the impact of provision. When working with more able pupils, in cognitively challenging learning environments, the aim is to extend assessment practices to include assessment of higher-order, complex and abstract thinking.

When used well, assessment provides the teacher with a detailed understanding of the pupils’ starting points, what they know, what they need to know and what they have the potential to do with their learning. The teacher can then plan an engaging and exciting learning journey which provides more able pupils with the cognitive challenge they need, without creating cognitive overload.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has joined with others to recognise the importance of cognitive science to inform interventions and classroom practice. Spaced learning, interleaving, retrieval practice, strategies to manage cognitive load and dual coding all support cognitive development – but are dependent on effective assessment practices which guide the teaching and learning. The best assessment methods are those that integrate fully within curriculum teaching and learning.

Assessment and classroom management

It is important to place the learner at the centre of any curriculum plan, classroom organisation and pedagogical practice. Initially the teacher must understand the pupils’ strengths and weaknesses, together with the skills and knowledge they possess, before engaging in new learning. This understanding facilitates curriculum planning and classroom management, which have been recognised as essential elements of cognitively challenging learning. Often, learning time is lost through additional testing and data collection, but when working in cognitively challenging environments, planned learning should be structured to include assessment points within the learning rather than devising separate assessment exercises.

When assessing cognitively challenging learning, pupils need opportunities to demonstrate their abilities using analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. They must also show how they use their existing knowledge in new, creative, or complex ways, so questions might include opportunities to distinguish between fact and opinion, to compare, or describe differences. The problems may have multiple solutions or alternative methodologies. Alternatively, pupils may have to extend learning by combining information shared with the class and then adding new perspectives to develop ideas.

Assessing cognitively challenging learning will also include measures of pupils’ abilities to think strategically and extend their thinking. Strategic thinking requires pupils to reason, plan, and sequence as they make decisions about the steps needed to solve problems, and assessment should measure this ability to make decisions, explain solutions, justify their methods, and obtain meaningful answers. Assessments which demonstrate extended thinking will include investigations, research, problem solving, and applications to the real world. Pupils’ abilities to extend their thinking can be observed through problems with multiple conditions, a range of sources, or those drawn from a variety of learning areas. These problems will take pupils beyond classroom routines and previously observed problems. Assessment at this level does not depend on a separate assessment task, but teaching and learning can be reviewed and evaluated within the learning process itself.

Assessment in language-rich learning environments

Language-rich learning environments support cognitive challenge, high-order thinking and deep learning for more able pupils. It is therefore inevitable that language, questioning and dialogic discourse are key elements of formative assessment. They allow the teacher to assess learning in the moment and adjust the course of learning to adapt to the needs of the pupils.

Assessment in the moment, utilising effective questions and dialogic discourse, does not happen by accident, but is planned into the learning. When planning a lesson, the big ideas and essential questions which will expose, extend and deepen the learning are central to the planning and assessment. When posing the planned questions or creating opportunities for discourse, pupils need time to formulate their ideas and think before discussing the responses and extending learning with their own questions and ideas.

Within the language-rich classroom where an understanding of assessment is shared with pupils, the ownership of learning can be passed to them. The teacher will introduce the theory, necessary linguistic skills, and technical language, using these to model good questions and questioning techniques. More able pupils will develop their own oracy, language and questioning techniques, and then develop them together. Through regular practice and good classroom routines, pupils gain the confidence and skills to ask ‘big questions’ themselves and engage in dialogue. At this point, discussion and questioning becomes an effective mode of ongoing assessment. As pupils explain their thinking, misconceptions or gaps in knowledge will be exposed, allowing the teacher to assess, support learning, and encourage deeper thinking.

Priorities for effective assessment

Within the classroom, the teacher needs to use assessment:

- To understand what the pupils know already;

- To promote and sustain cognitive challenge and progression:

- To measure the impact of both the teaching and the learning;

- To adapt practice in a timely manner;

- To support, extend and enhance learning;

- To examine how effectively the knowledge is used in new, varied and complex contexts.

Assessment has the potential to support pupils as learners as they will:

- Understand the nature and purpose of activities so that they can benefit from them;

- Appreciate the demands of learning;

- Engage in the learning journey;

- Develop their own cognitive skills and learning attributes;

- Take action to improve themselves;

- Take ownership of learning;

- Become increasingly autonomous and self-regulating.

Assessment is not a separate part of teaching and learning, but should be planned within the teaching. Assessment should not distract pupils from learning, and learning should not be framed to meet assessment criteria. Assessment is not about data gathering and organisational checks, but it should lead to enriched learning and refined practice with teachers and pupils working together to achieve an exciting learning environment.

What next?

This year, NACE is focusing on exploring effective assessment practices within Challenge Award-accredited schools. We hope that many schools will participate in this project, to provide evidence and share examples of effective assessment: what works, how, and why? By sharing our expertise with others we can move the conversation about assessment forwards and provide exciting and engaging learning for our pupils. To find out more or to express your school’s interest in contributing to this initiative, please contact communications@nace.co.uk

References

- Education Endowment Foundation (2021), Cognitive science approaches in the classroom (a review of the evidence)

- Rimfield. K, et.al. (2019), Teacher assessment during compulsory education are as reliable, stable, and heritable as standardized test scores. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 60(12) (1278-1288)

Read more:

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

myths and misconceptions

oracy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

22 March 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Curriculum Development Director

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami is one of my favourite books… even if reading it did not make me run faster. The title did, however, lead me to ask students: “What do you think about when you think about learning?” This is not an easy question to answer. We increasingly recognise the importance of developing metacognition in learning and the need to challenge pupils cognitively, but this is not always easy in the mixed ability classroom.

In the NACE report Making space for able learners – Cognitive challenge: principles into practice (2020), cognitive challenge is defined as “ how learners become able to understand and form complex and abstract ideas and solve problems”. We want students to achieve these high ambitions in their learning, but how is this achieved in a mixed ability class with increasing demands on the teacher, including higher academic expectations? The NACE report provides case studies showing where this has been achieved and highlights the common features across schools that are achieving this – and these key themes are worth reflecting upon. What do we mean by “challenge for all”?

“Challenge for all” is the mantra often recited, but is it a reality? At times it can appear that “challenge” is just another word for the next task. Or, perhaps, just a name for the last task. Working with teachers recently I asked: why do the more able learners need to work through all the preceding the tasks to get to the “challenge”? Are you asking them to do other work that is not challenging? Or coast until it gets harder? A month later the same teachers talked about how they now move those learners swiftly on to the more challenging tasks, noting that their work had improved significantly, they were more motivated and the learning was deeper. This approach also led to learners being fully engaged, meaning the teacher could vary the support needed across the class to ensure all pupils were challenged at the appropriate level.

“Teaching to the top” is another phrase widely used now and it is a good aspiration, although at times it is unclear what the “top” is. Is it grade 7 at GCSE or perhaps greater depth in Year 6? It is important to have these high expectations and to expose all learners to higher learning, but we need to remember that some of our learners can go even higher but also be challenged in ways that do not relate to exams. For instance, at Copthorne Primary School, the NACE report notes that “pupils are regularly set complex, demanding tasks with high-level discourse. Teachers pitch lessons at a high standard”. Note the reference to discourse – a key feature of challenge is the language heard in the classroom, whether from adults or learners. The “top” is not merely a grade; it is where language is rich and learning is meaningful, including in early years, where we often see the best examples.

Are your questions big enough?

The use of “low threshold, high ceiling” tasks are helpful in a mixed ability class, with all pupils able to access the learning and some able to take it further. In maths, a question as simple as “How many legs in the school?” can lead to good outcomes for all (including those who realise the question doesn’t specify human legs). But there is often a danger that task design can be quite narrow. The minutiae of the curriculum can push teachers to bitesize learning, which can be limiting – especially when a key aim has to be linking the learning through building schema. Asking “Big Questions” can extend learning and challenge all learners. The University of Oxford’s Oxplore initiative offers a selection of Big Questions and associated resources for learners to explore, such as “Should footballers earn more than nurses?” and “Can money buy happiness?”. There is a link to philosophy for children here, and in cognitively challenging classrooms we see deep thinking for all pupils. Can your learners build more complex schema?

All pupils need to build links in their learning to develop understanding, and more able learners can often build more detailed schema. To give a history example, understanding the break from Rome at the time of Henry VIII could be learned as a series of separate pieces of knowledge: marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the need for a male heir, wanting a divorce in order to marry Anne Boleyn, the religious backdrop, etc. Knowing these items is one thing, but learners need to make links between them and create a schema of understanding. The more able the pupil, the more links can be made, again deepening understanding. That is why in cognitively challenging classrooms skilled teachers ask questions such as:

- What does that link to?

- What does that remind you of?

- When have you seen this before?

- What is this similar to? Why?

These questions are especially useful in a busy mixed ability classroom. Prompt questions like these can be used in a range of situations, rather than always requiring another task for the more able pupil who has “finished”. (As if we have ever really finished)

Are you allowing time for “chunky” problems?

So, what else provides challenge? The NACE report notes: “At Portswood Primary School pupils are given ill-structured problems, chunky problems, and compelling contexts for learning”. Reflecting upon the old literacy hour, I used to joke: “Right Year 5, you have 20 minutes to write like Charles Dickens. Go!” How could there be depth of response and high-level work in such short time scales? What was needed were extended tasks that took time, effort, mistakes, re-writes and finally resolution. The task often needed to be chunky. Some in the class will need smaller steps and perhaps more modelling from the teacher, but for the more able learners their greater independence allows them to tackle problems over time.

This all needs organising with thought. It does not happen by accident. With this comes a sense of achievement and a resolution. Pupils are challenged cognitively but need time for this because they become absorbed in solving problems. This also works well when there are multiple solution paths. In a mixed ability class asking the more able to find two ways to solve a problem and then decide which was the most efficient or most effective can extend thinking. It also calls upon higher-order thinking because they are forced to evaluate. Which method would be worth using next time? Why? Justify. This also emphasises the need to place responsibility with the learner. “At Southend High School for Boys, teachers are pushed to become more sophisticated with their pedagogy and boost pupils’ cognitive contribution to lessons rather that the teacher doing all the work”. In a mixed ability class this is vital. How hard are your pupils working and, more importantly, thinking?

I wrote in a previous blog post about how essential the use of cutaway is in mixed ability classes. Retrieval practice, modelling and explanation are vital parts of a lesson, but the question is: do all of the students in your class always need to be part of that? A similar argument is made here. More able learners are sometimes not cognitively challenged as much in whole-class teaching and therefore, on occasion, it is preferable for these pupils to begin tasks independently or from a different starting point.

As well as being nurturing, safe and joyful, we all want our classrooms to be cognitively challenging. This is a certainly not easy in a mixed ability class but it can be achieved. High expectations, careful task design and an eye on big questions all play a part, alongside the organisation of the learning. In this way our teaching can be improved significantly – far more than my running ever will be…

Related blog posts

Additional reading and support

Tags:

cognitive challenge

grouping

metacognition

problem-solving

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Lauren Bellaera,

03 March 2021

|

Dr Lauren Bellaera is Director of Research and Impact at The Brilliant Club, a UK-based charity which aims to increase the number of pupils from under-represented backgrounds that progress to highly selective universities. In this blog post (originally published on The Learning Scientists website), Dr Bellaera explores research-informed approaches to develop critical thinking skills in the classroom – ahead of her forthcoming live webinar on this theme for NACE members (recording available to watch back when logged in as a member).

What is critical thinking?

Many definitions of critical thinking exist – far too many to list here! – but one key definition that is often used is:

“[the] purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which judgment is based” (1, p. 3).

Despite the different definitions, there is a consensus regarding the dimensions of critical thinking and these dimensions have implications for how critical thinking is understood and taught. Critical thinking includes skills and dispositions (1). The former refers to reasoning and logical thinking, e.g., analysis, evaluation, and interpretation, whereas the latter refers to the tendency to do something, e.g., being open-minded (2). This blog post primarily is referring to the development of critical thinking skills as opposed to dispositions.

Critical thinking can be subject-specific or general, and thus can either be embedded within a specific subject or it can be developed independently of subject knowledge – something that we will revisit later.

How are critical thinking skills developed?

Developing critical thinking is often regarded as the cornerstone of higher education, but the reality is that many educational institutions are failing to develop critical thinking consistently and reliably in their students, with only around 6% of university graduates considered proficient (3), (4), (5).

Thus, there is a disconnect between the value of critical thinking and the degree to which it is supported by effective instruction (6). So, what does effective instruction look like? Helpfully, cognitive psychology provides us with some of the answers:

1. Context is king: the importance of background knowledge

The important question at hand here is: are some types of critical thinking more difficult to develop than others? The short answer is yes – subject-specific critical thinking appears to be easier to develop than general critical thinking. Studies have shown that critical thinking interventions improve subject-specific as opposed to general critical thinking (7), (8). This is also what we have found in our own research (9).

Possible reasons for why this is the case include the fact that the length of time needed to develop general critical thinking is much greater. This is coupled with the idea that general critical thinking is simply not as malleable as subject-specific critical thinking (10). For balance, though, some studies have reported improvements in general critical thinking, indicating that under the right circumstances, general improvement is possible (6), (11). The key message here is that background knowledge is an important part of teaching critical thinking and the extent to which you aim to develop critical thinking beyond the scope of the course content should be assessed dependent on what is achievable in the given context.

2. Be explicit: approaches to critical thinking instruction

The importance of background knowledge also has implications for critical thinking instruction (12). There are four main approaches to critical thinking instruction; general, infusion, immersion and mixed (13):

The general approach explicitly teaches critical thinking as a separate course outside of a specific subject. Content can be used to structure examples and activities but it is not related to subject-specific knowledge and tends to be about everyday events.

The infusion approach explicitly teaches both subject content and general critical thinking skills, where the critical thinking instruction is taught in the context of a specific subject.

Similarly, the immersion approach also teaches critical thinking within a specific subject, but it is taught implicitly as opposed to explicitly. This approach infers that critical thinking will be a consequence of interacting with and learning about the subject matter.

Lastly, the mixed approach is an amalgamation of the above three approaches where critical thinking is taught as a general subject alongside either the infusion or immersion approach in the context of a specific subject.

In terms of which are the best instructional approaches to adopt, evidence from a meta-analysis of over 100 studies showed that explicit approaches led to the greatest increase in critical thinking compared to implicit approaches. Specifically, the mixed approach where critical thinking was taught explicitly as a separate strand and within a specific subject was the most effective, whereas the implicit immersion approach was the least effective. This research suggests that developing critical thinking skills separately and then applying them to subject content explicitly works best (14).

3. Be strategic: effective teaching strategies

The knowledge that critical thinking needs to be deliberately and explicitly built into courses is integral to developing critical thinking. However, without the more granular details of exactly what teaching strategies sit beneath this, it will only get us so far. A number of teaching strategies have been shown to be effective, including the following:

Both answering and generating higher-order thinking questions have been shown to increase critical thinking (8) (14). For example, psychology students who were given higher-order thinking questions compared to lower-order thinking questions significantly improved their subject-specific critical thinking (8). Alison King’s work on higher-order questions provides some useful examples of question stems (15).

Ensuring that critical thinking is anchored in authentic instruction that allows students to engage with problems that make sense to them, and that enables further inquiry, is important (6). Some ways to facilitate authentic instruction include simulations and applied problem solving.

Closely related to higher-order questions and authentic instruction is dialogue – essentially discussions are needed to develop critical thinking. Teachers asking questions is particularly beneficial to the development of critical thinking, in part because teachers will often be asking questions that require higher-order thinking. A meta-analysis study showed that authentic instruction and dialogue were particularly effective for developing general critical thinking (6).

Engaging pupils in explicit self-reflection techniques promotes critical thinking. For example, asking students to judge their performance on a paper can increase their ability to understand where they need to improve and develop in the future (16). Other formalisations of this include reflection journals (17). In my current role, we also employ self-reflection activities to increase critical thinking.

So, to conclude, remember when developing critical thinking skills that context is king, always be explicit and always be strategic!

Find out more… On 29 April 2021 Dr Bellaera presented a live webinar for NACE members exploring the research on critical thinking and how to apply it in your school. Watch the recording here (login required). Plus: Dr Bellaera's research paper on critical thinking is available to read and download here until 4 August 2021.

References:

(1) Facione, P. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (The Delphi Report).

(2) Ennis, R. H. (1996). Critical thinking. Upper-Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

(3) American Association of Colleges and Universities (2005). Liberal education outcomes: Preliminary report on student achievement in college. Washington, DC: AAC&U.

(4) Dunne, G. (2015). Beyond critical thinking to critical being: Criticality in higher education and life. International Journal of Educational Research, 71, 86-99.

(5) Ku, K. Y. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 70- 76.

(6) Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D. I., Wade, C. A., & Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for teaching students to think critically: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85, 275-314.

(7) Williams, R. L., Oliver, R., & Stockdale, S. (2004). Psychological versus academic critical thinking as predictors and outcome measures in a large undergraduate human development course. The Journal of General Education, 53, 37-58.

(8) Renaud, R. D., & Murray, H. G. (2008). A comparison of a subject-specific and a general measure of critical thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3, 85-93.

(9) Bellaera, L., Debney, L., & Baker, S. (2018). An intervention for subject comprehension and critical thinking in mixed academic ability university students. The Journal of General Education.

(10) Facione, P. A., Facione, N. C, & Giancarlo, C. A. (2000). The disposition toward critical thinking: Its character, measurement, and relationship to critical thinking skill. Informal Logic, 20, 61-84.

(11) Halpern, D. F. (2001) Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. The Journal of General Education, 50, 270–286.

(12) Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson's Research Reports, 6, 1-49.

(13) Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educational Researcher, 18, 4-10.

(14) Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78, 1102-1134.

(15) King, A. (1995). Designing the instructional process to enhance critical thinking across the curriculum. Teaching of Psychology, 22, 13-17.

(16) Austin, Z., Gregory, P. A., & Chiu, S. (2008). Use of reflection-in-action and self-assessment to promote critical thinking among pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72, 1-8.

(17) Mannion, J., & Mercer, N. (2016). Learning to learn: Improving attainment, closing the gap at Key Stage 3. The Curriculum Journal, 27, 246-271.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

metac

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

27 January 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Associate

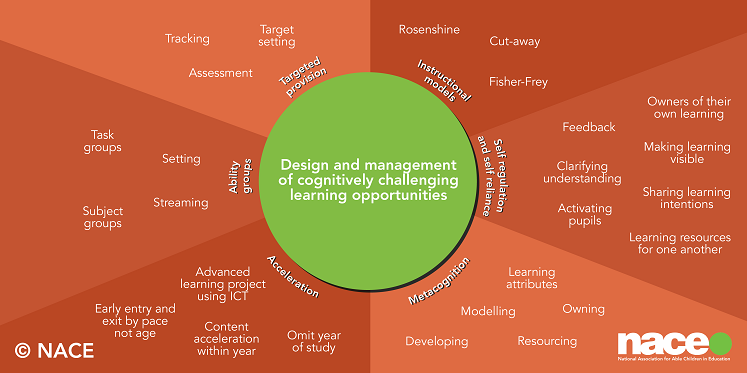

In recent years many new developments in teaching have been most welcome and have helped the shift towards a more research-informed profession. NACE’s recent report Making space for able learners – Cognitive challenge: principles into practice provides examples of strategies used for the design and management of cognitively challenging learning opportunities, including reference to Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction (2010) which outline many of these strategies.

These principles of instruction are particularly influential in current teaching, which is pleasing to the many good teachers who have been used them for years, although they may not have attached that exact language to what they were doing. These principles are especially helpful for early career teachers, but like all principles they need to be constantly reflected upon. I was always taken by Professor Deborah Eyre’s reference to “structured tinkering” (2002): not wholesale change but building upon key principles and existing practice.

This is where “cutaway” comes in – another of the strategies identified in the NACE report, and one which I would like to encourage you to “tinker” with in your approach to ability grouping and ensuring appropriately challenging learning for all.

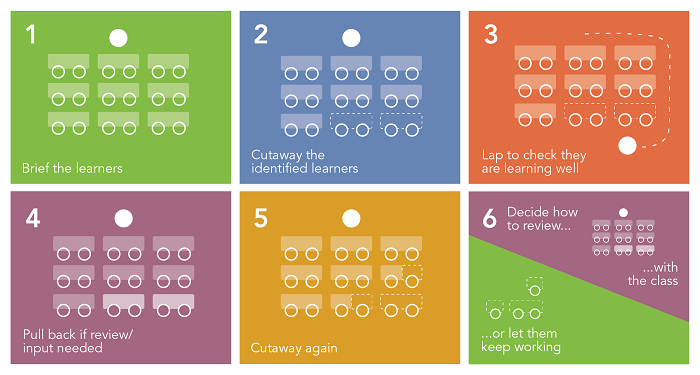

What is “cutaway” and why use it?

The “cutaway” approach involves setting high-attaining students off to start their independent work earlier than the vast majority of the class, while the teacher continues to provide direct instruction/ modelling to the main group. In this way the high attainers can begin their independent work more quickly and can avoid being bored by the whole class instruction which they can find too easy, even when the teacher is trying to “teach to the top”. Once the rest of the class has begun their independent work, the teacher can then focus on the higher attaining group to consolidate the independent work and extend them further.

There are more nuances which I will explain later, but you may wonder, how did this way of working come about?

An often-quoted figure from the National Academy of Gifted and Talented Youth (NAGTY) was that gifted students may already have acquired knowledge of 40-50% of their lessons before they are taught. If I am honest, this was 100% in some of my old lessons! With whole class teaching, retrieval practice tasks and modelling (all essential elements in a lesson), there are clear dangers of pupils being asked to work on things they already know well. There is the issue of what Freeman, (quoted in Ofsted, 2005:3), called the “three-time problem” where: “Pupils who absorb the information the first time develop a technique of mentally switching off for the second and the third, then switching on again for the next new point, involving considerable mental skill.” Why waste this time?

The idea of “cutaway” was consolidated when I carried out a research project involving the use of learning logs to improve teaching provision for more able learners (Watson, 2005). In this project teachers adapted their teaching based on pupil feedback. The teachers realised that, in a primary classroom, keeping the pupils too long “on the carpet” was inappropriate and the length of time available to work at a high level was being minimised. One of the teachers reflected: “Sometimes during shared work on the carpet, when revising work from previous lessons to check the understanding of other pupils, I feel aware of the more able children wanting to move on straight away and find it difficult to balance the needs of all the children within the Year 5 class.”

It therefore became common in lessons (though not all lessons) to cutaway pupils when they were ready to begin independent work. By using “cutaway” the pupils use time more effectively, develop greater independence, can move through work more quickly and carry out more extended and more challenging tasks. The method was commented upon favourably during a HMI inspection that my school received and has ever since been a mainstay of teaching at the school.

Who, when and how to cutaway

So how does a teacher decide when and who to cutaway? The method is not needed in all lessons, the cutaway group should vary based upon AfL, and at its best it involves pupils deciding whether they feel they need more modelling/explanation from the teacher or are ready to be cutaway. In a recent NACE blogpost on ability grouping, Dr Ann McCarthy emphasises that in using cutaway “the teacher constantly assesses pupils’ learning and needs and directs their learning to maximise opportunities, growth and development” and pupils “leave and join the shared learning community”. This underlines the importance of the AfL nature of the strategy and the importance of developing learners’ metacognition, which was another key finding in the NACE report.

Sometimes the cutaway approach is decided on before a lesson by the teacher based upon previous work. In GCSE history, a basic retrieval task on the Norman invasion could be time wasted for a more able pupil who has secure knowledge, whereas being cutaway to do an independent task centred on the role of the Pope in supporting William would be more challenging and worthwhile. It comes down to one key question a teacher needs to ask themselves when speaking to the whole class: “Who do I need here now?” Who needs to retrieve this knowledge? Who needs to hear this explanation? Who needs to see this model or complete this example? If a small group of higher attainers do not need this, then why slow the pace of their learning? Why not start them either on the same work independently or more challenging work to accelerate learning?

Why not play around with this idea? Explain your thinking to the pupils and see how they respond. Sometimes, at the end of one lesson, a task for the next lesson can be explained and the pupils could start the next lesson by working on that task straight away. The 2015 Ofsted handbook said, “The vast majority of pupils will progress through the programmes of study at the same rate”, and ideally, they will. However, a few pupils will progress at a faster rate and therefore need adapted provision. The NACE research and accompanying CPD programme suggests the use of “cutaway” can achieve this and it is well worth all teachers doing some “structured tinkering” with this strategy.

References

Additional reading and support

Share your views

How do you use ability grouping, and why? Share your experiences by commenting on this blog post or by contacting communications@nace.co.uk

Tags:

cognitive challenge

differentiation

grouping

independent learning

pedagogy

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 January 2021

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Associate and co-author of NACE’s new publication “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”.

To group or not to group: that is the question…

The organisation and management of cognitively challenging learning environments is one of three focus areas highlighted in NACE’s new research publication, “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”, which marks the first phase in our “Making Space for Able Learners” project. Developed in partnership with NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools, the research examines the impact of cognitive challenge in current school practice against a backdrop of relevant research.

As teachers, we aim to provide a cognitively challenging learning environment for our more able and exceptionally able pupils, which is beneficial to them. The organisational decisions surrounding this should therefore optimise opportunities for learning. Teachers and school leaders must not only consider content to be studied, but also the impact of classroom management decisions from the perspective of the learner. The NACE research showed that these classroom management and organisational decisions were one of three key factors impacting on cognitively challenging learning, alongside curriculum organisation and design and the use of rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse.

One aspect of managing cognitively challenging learning environments is any choice relating to mixed ability teaching versus a variety of designs for selection and grouping by ability. Within the classroom the teacher also balances demands to provide opportunities for all, while simultaneously identifying the nature and opportunity for challenge.

Does ability grouping benefit learners?

There is a paucity of strong evidence that ability grouping is beneficial to academic outcomes for all. However, Parsons and Hallam (2014) did find that grouping can benefit more able pupils. This benefit is not necessarily associated with the act of setting, but with the quality of teaching provided for these groups. Pupils also have opportunities to work at a faster pace, but against this aspiration, Boaler et al. (2000) found pace incompatible with understanding for many pupils. Regardless of the choice made to group or not to group, there is a need to reflect on whether teaching is homogenous or designed to meet the needs of the pupils. Often the weakness is the assumption that grouping alone will drive the learning experience, without an understanding of the cognitive and emotional impact this has on the pupils themselves.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has examined the use of setting and streaming, which are usually related to attainment rather than ability, and has found that there is often a small negative impact for disadvantaged pupils and lower abilities. When designing learner groupings, it is important to be aware of the impact for all learners and create a beneficial model for all.

How should teachers and schools approach ability grouping?

First, decide what you hope to teach and what it is pupils have the potential to achieve, given enough learning opportunities. Remember, learning is not limited to reproducing planned content by rote, but instead its success lies within a growth of knowledge, its complexity, and its application. Pupils bring a wide range of prior learning, knowledge and experiences which they can share with each other and use to construct new schema. In a well-designed learning environment, pupils have the potential to develop their knowledge, skills and understanding beyond the delivered content. Young et al. (2014) demonstrate the importance of powerful knowledge which takes pupils beyond their own experiences. The development of metacognition and exposure to wider experience should therefore be included in decisions related to the organisation of groups and lesson planning.

Second, decide what environment will provide the best learning experience for the pupils.

- Is it best to present advanced curricula at an accelerated rate?

- Does teaching include multiple high-order thinking models and skills?

- Is learning pupil-centred?

- Are multiple modality enquiry methods in play?

- Will grouping take account of the complexity of ability and enhance its manifestation?

- Will pupils benefit from a wide range of perspectives?

- Will pupils utilise the learning experiences of others to reflect upon and refine their own learning?

The answers to these questions will help teachers to make decisions regarding the nature of grouping and classroom organisation. The choice of model should be one which most benefits the learner, one which is not driven by systemic organisational requirements, and one which recognises the impact of external factors on perceived ability.

Finally, what models are available and how can cognitive challenge be achieved within them?

- Mixed ability grouping has the benefit of exposing pupils to the wider knowledge, background, and experience of others. In these environments, problems with different layers of complexity and multiple learning routes are often used. The big question or cognitively challenging proposition often promotes the learning with supporting systems and prompts in place for those challenged by the learning.

- Cutaway models are an alternative to the simpler mixed ability model. In the cutaway approach, the teacher constantly assesses pupils’ learning and needs and directs their learning to maximise opportunities, growth, and development. Pupils join and leave the shared learning (“cutting away” as appropriate), based on prior learning and their response to the existing task. This model develops and utilises independence and metacognition.

- Grouping by task is often used when it is possible to create smaller groups working on different tasks within the same classroom. The teacher uses very specific knowledge relating to pupils’ prior learning and abilities to organise the classroom groups. The teacher can therefore target the teaching to respond to more specific learning opportunities, which in turn can increase pupils’ enjoyment and engagement in their learning.

- Grouping by subject is an extension of grouping by task. If pupils learn all their subjects within the same class group, this enables the teacher to note the different strengths within the subject. In larger schools, pupils are often grouped by overall performance in specific subjects. This model might include advanced curriculum and require higher-order thinking skills. Pupils might be given opportunities to research more deeply into areas of interest. For this model to be successful there needs to be fluidity between the groups so that pupils are well-placed to enjoy cognitively challenging experiences.

With these ideas in mind, schools will then create an overarching model which reflects the school vision, ethos and culture. Teachers will consistently strive to provide cognitively challenging learning opportunities which benefit all. They use their knowledge of the pupils’ past and present learning and their vision of what the pupils can be and can achieve in the future to design the learning environment. They then organise the classroom to excite, engage and challenge their pupils – remembering that regardless of the sophistication of the approach, every group will be mixed ability as no two pupils are identical. If high-quality and engaging teaching is child-centred and not homogenous, then pupils will excel in cognitively challenging classrooms.

References