Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Jonathan Doherty,

19 May 2022

|

Dr Jonathan Doherty, NACE Associate

Covid-19 has presented schools with unprecedented challenges. Pupils, parents and teachers have all been affected, and the wider implications in schools are far from over. From May 2020, over 1.2 billion learners worldwide have experienced school closures due to Covid-19, which corresponds to 73.8% of enrolled learners (Muller & Goldenberg, 2021). The pandemic continues to have a significant effect in all phases of our education system. This blog post captures some key messages from research into the effects of Covid-19 over the past two years and highlights the effects it has had on young people – particularly on the development of language and communication skills.

1. The pandemic negatively affected achievement. Vulnerable pupils and those from economically deprived backgrounds were most affected.

When pupils do not attend school (whilst acknowledging that much great work is done at home), the disruption has a negative impact on their academic achievement (Sims, 2020).

The disrupted periods of partial school closures in England took a toll academically. DfE research (Pupils' progress in the 2020 to 2022 academic years) showed that in summer 2021, pupils were still behind in their learning compared to where they would otherwise have been in a typical year. Primary school pupils were one month behind in reading and around three months behind in maths. Data for secondary pupils suggest they were behind in their reading by around two months.

Primary pupils eligible for free school meals were on average an additional half month further behind in reading and maths compared to their more advantaged peers. Research has highlighted that the attainment gap between disadvantaged children and others is now 18 months by the end of Key Stage 4. Vulnerable pupils with education, health and care (EHC) plans scored 3.62 grades below their peers in 2020 and late-arriving pupils with English as an additional language (EAL) were 1.64 grades behind those with English as a first language (Hunt et al., 2022).

2. Remote teaching during Covid changed the nature of learning – including reduced learning time and interactions – further widening existing gaps.

‘Learning time’ is the amount of time during which pupils are actively working or engaged in learning, which in turn is connected to academic achievement. Pre-pandemic (remember those days?!), the average mainstream school day in England for primary and secondary settings was around six hours 30 minutes a day. The difference between primary and secondary is minimal and averages out at 9 minutes a day.

During the period up to April 2021, mainstream pupils in England lost around one third of learning time (Elliot Major et al., 2021). We know that disadvantaged pupils continue to be disproportionately affected by the pandemic. Levels of lost learning remain higher for pupils in more deprived areas.

School provision for online learning changed radically since the beginning of the first lockdown. Almost all pupils received some remote learning tasks from their teachers. Just over half of all pupils taught remotely did not usually have any online lessons, defined as live or real-time lessons. Offline provision, such as worksheets or recorded video, was much more common than live online lessons, but inevitably reduced the opportunities for pupil-pupil interactions.

Parents reported that for most pupils, time spent on schoolwork fell short of the expected school day (Eivers et al., 2020). Pupil participation was, on average, poorer amongst those from lower income families and those whose parents had lower levels of education (Eivers et al., 2020). Families from higher socio-economic backgrounds spend more financially to support their children’s online remote learning. At times, technological barriers, as well as significant differences in the amount of support pupils received for learning at home, resulted in a highly unequal experience of learning during this time.

3. There has been a negative impact on pupils’ wellbeing, socio-emotional development and ability to learn.

A YoungMinds report in 2020 reinforced the effect of the pandemic on pupils’ mental health. In a UK survey of participants aged up to 25 years with a history of mental illness, 83% of respondents felt that school closures had made their mental illness worse. 26% said they were unable to access necessary support.

Schools play a key role in supporting children who have experienced bereavement or trauma, and socio-emotional interventions delivered by school staff can be very effective. Children with emotional and behavioural disorders also have significant difficulties with speaking and understanding, which often goes unidentified (Hollo et.al., 2014).

The experience of lockdown and being at home is a stressful situation for some children, as is returning to school for some children. While some studies found that children are not affected two to four years later, other studies suggest that there are lasting effects on socio-emotional development (Muller & Goldenberg, 2021).

Stress also challenges cognitive skills, in turn affecting the ability to learn. Trauma, emotional and social isolation, all well-known during the lockdown, are still too frequent. The prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain which is responsible for higher-order thinking and decision-making, is the brain region most affected by stress. Stress-related impairments to the prefrontal cortex display impaired memory retrieval (Vogel & Schwabe, 2016) and difficulties with executive skills such as planning, problem solving and monitoring errors (Gibbs et al., 2019).

4. National restrictions have curtailed the pandemic but had an adverse effect on communication and language.

Covid-19 and the associated lockdowns have had a huge impact on children’s speaking and listening skills. We are only beginning to understand the scale of this. Preventative measures such as the wearing of face masks in school, social distancing and virtual lessons, all designed to address contagion concerns, have negatively impacted on communication in all the school phases.

Face masks cover the lower part of the face, impacting on communication by changing sound transmission. They remove visible cues from the mouth and lips used for speech-reading and limit visibility of facial expressions (Saunders, 2020). Speech perception involves audio-visual integration of information, which is diminished by wearing masks because articulatory gestures are obscured. Children with hearing loss are more dependent on lip-reading; loss of this visual cue exacerbates the distortion and attenuation effects of masks.

Social interaction is also essential for language development. Social distancing restrictions on large group gatherings in school have affected children’s deeper interactions with peers. “Peer talk” is an essential component of pragmatic language development and includes conversational skills such as turn taking and understanding the implied meaning behind a speaker’s words, and these have also been reduced (Charney, 2021).

How bad is the issue? A report from the children’s communication charity I CAN estimates that more than 1.5 million UK children and young people risk being left behind in their language development as a direct result of lost learning in the Covid-19 period. Speaking Up for the Covid Generation (I CAN, 2021) reported that the majority of teachers are worried about young people being able to catch up with their speaking and understanding. Amongst its findings were that:

- 62% of primary teachers surveyed were worried that pupils will not meet age-related expectations

- 60% of secondary teachers surveyed were worried that pupils will not meet age-related expectations

- 63% of primary and secondary teachers surveyed believe that children who are moving to secondary school will struggle more with their speaking and understanding, in comparison to those who started secondary school before the Coronavirus pandemic.

Measures taken to combat the pandemic have deprived children of vital social contact and experiences essential for developing language. Reduced contact with grandparents, social distancing and limited play opportunities mean children have been less exposed to conversations and everyday experiences. Oracy skills have been impacted by the wearing of face coverings, fewer conversations with peers and adults, hearing fewer words and remote learning where verbal interactions are significantly reduced.

Teachers are now seeing the impact of this in their classrooms. The I CAN report findings show that the majority of teachers are worried about the effect that the pandemic has had on young people’s speech and language. As schools across the UK start on their roads to recovery and building their curricula anew, this evidence reveals the major impact the pandemic has had on children’s speaking and understanding ability. The final Covid-19-related restrictions in England have now been removed, but for many young people and families, this turning point does not mark a return to life as it was before the pandemic. There is much to do now to prioritise communication.

Join the conversation…

As schools move on from the pandemic and seek to address current challenges, close gaps, and take oracy education to the next level, NACE is focusing on research into the role of oracy within cognitively challenging learning. This term’s free member meetup will bring together NACE members from all phases and diverse contexts to explore what it means to put oracy at the heart of a cognitively challenging curriculum – read more here.

Plus: to contribute to our research in this field, please contact communications@nace.co.uk

References

Charney, S.A., Camarata, S.M. & Chern, A. (2021). Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Communication and Language Skills in Children. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery 2, Vol. 165(1) pp. 1-2.

Elliot Major, L., Eyles, A. & Machin, S. (2021). Learning Loss Since Lockdown: Variation Across the Home Nations [online]. Available at: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/cepcovid-19-023.pdf

Eivers, E., Worth, J. & Ghosh, A. (2020). Home learning during Covid-19: findings from the Understanding Society longitudinal study. Slough: NFER.

Gibbs L., Nursey, J., Cook J. et al. (2019). Delayed disaster impacts on academic performance of primary school children. Child Development 90(4): pp. 1402-1412.

Hollo, A., Wehby, J. H., & Oliver, R. M. (2014). Unidentified language deficits in children with emotional and behavioural disorders: a meta-analysis. Exceptional Children 80 (2), pp.169-186.

Hunt, E. et al. (2022) COVID-19 and Disadvantage. Gaps in England 2020. London: Education Policy Institute. Nuffield Foundation.

I CAN (2021) Speaking Up for the Covid Generation. London: I CAN.

Muller, L-M. & Goldenberg, G. (2021) Education in times of crisis: The potential implications of school closures for teachers and students. A review of research evidence on school closures and international approaches to education during the COVID-19 pandemic. London: Chartered College of Teaching.

Saunders, G.H., Jackson, I.R. & Visram, A.S. (2020): Impacts of face coverings on communication: an indirect impact of COVID-19. International Journal of Audiology, DOI: 10.1080/14992027.2020.1851401

Sims, S. (2020) Briefing Note: School Absences and Pupil Achievement. UCL. Available at: https://repec-cepeo.ucl.ac.uk/cepeob/cepeobn1.pdf

Vogel, S. & Schwabe, L. (2016) Learning and memory under stress: implications for the classroom. Science of Learning 1(1): pp.1-10.

YoungMinds (2020) Coronavirus: Impact on young people with mental health needs. Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/media/3708/coronavirus-report_march2020.pdf

Tags:

confidence

disadvantage

language

lockdown

oracy

pedagogy

remote learning

research

resilience

underachievement

vocabulary

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

25 April 2022

Updated: 21 April 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research & Development Director, shares examples from our recent member meetup on the theme “rethinking assessment”.

As part of NACE’s current research into effective assessment strategies, we recently brought our member schools together for a meetup at New College Oxford, to share thoughts and examples of successful practice. We examined assessment as a systematic procedure drawing from a range of activities and evidence. We saw how this contrasted with the necessary but limiting practice of testing, which is a product not open to interpretation.

Practitioners attending the meetup generously shared established and emerging approaches to assessment and were able to discuss the related strengths and challenges. They had time to examine the ways in which new practices had been introduced and strategies used to overcome any barriers or difficulties. Most importantly, they articulated the positive impact that these practices were having on the learning and development of pupils in their care.

When schools develop successful assessment strategies, they consider the following questions:

- How does it link to whole school vision?

- Where does it sit inside the model for curriculum, teaching and learning?

- Who is the assessment for?

- What is the plan for assessment?

- What types of assessment can be used?

- What is going to be assessed?

- What evidence will result from the assessment?

- How will the evidence be used or interpreted?

- How can assessment information be used by teacher and pupil?

- What impact does assessment information have on teaching and learning?

- How does assessment impact on cognition, cognitive strategies, metacognition and personal development?

Example 1: “purple pen” at Toot Hill School

Toot Hill School shared how the use of the “purple pen” strategy can be effective in developing the learning and metacognition of secondary-age pupils.

Pupils most commonly receive feedback at three stages in the learning process:

- Immediate feedback (live) – at the point of teaching

- Summary feedback – at the end of a phase of knowledge application/topic/assessment

- Review feedback – away from the point of teaching (including personalised written comments)

A purple pen can be used to:

- Annotate purposeful learning steps;

- Make notes when listening to key learning points;

- Respond to whole-class feedback;

- Facilitate peer assessment;

- Respond to teacher marking;

- Question and develop themes to achieve learning objectives;

- Recognise key vocabulary;

- Explain learning processes.

Much of the success of this strategy at Toot Hill School can be attributed to the clear teaching and learning strategy which is in place and the consistency of practice across the school. Some schools have used this practice in the past and abandoned it due to inconsistency, lack of evidence of impact or increased workload. At Toot Hill this is not the case as its introduction included a consideration of overall practice and workload. Pupils are fully conversant with the aims and expectations. Subject leaders are well-informed and work together to ensure that pupils moving between subjects have the same expectation. Here we find assessment planned carefully within ambitious teaching and learning routines.

This example of effective assessment demonstrates the importance of feedback within the assessment process. In this example pupils are being assessed but also assessing their own learning. They have greater control of their learning. This practice is particularly effective for more able learners, who will make their own notes on actions needed to improve. They are also influential in promoting good learning behaviours within their classrooms as they model actions needed for improved learning. This practice keeps the focus of assessment on the needs of the learner and the information needed by the learner to become more independent and self-regulating.

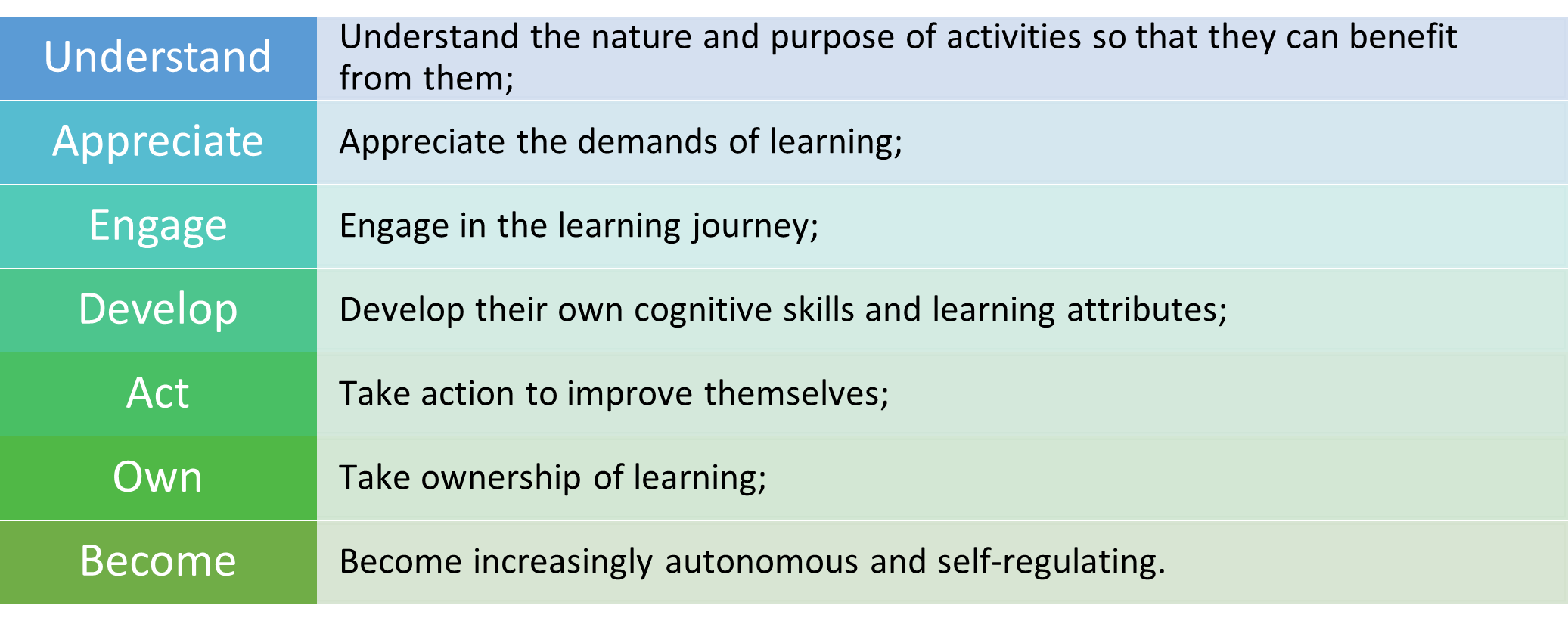

Successful assessment practice places the pupil at the heart of the process. Assessment enables pupils to:

Example 2: “closing the loop” at Eggar’s School

Eggar’s School shared details of an initiative which is being piloted, aiming to improve outcomes in formal assessments. A template for whole-class “feed-forward” sheets has been introduced. This shared template enables teachers to keep a track record of assessments. It also tracks their intentions to adapt their teaching as a result of evaluating student assessments. They are focusing on “closing the loop” in feedback and learning.

The rationale behind the strategy is that it is easier for teachers to:

- Reflect on attainment over the course of the year, comparing pieces of work by the same student over time;

- Compare attainment between year groups and ask: Has teaching improved? Are there different needs / interventions required in the current cohort compared with those of previous years?

- Get a snapshot of a student’s work.

The approach also allows the Lead Teacher and Curriculum Leader to spot-check progress and discuss successes or concerns with the class teacher.

As this is an emerging practice, the teachers are learning and adapting their practice to make it increasingly useful. The school’s findings include:

- The uniformity of the layout of the feed-forward sheets is helping students to understand the feed-forward process.

- Completion of the feed-forward sheets was originally time-consuming, but is now taking less time.

- In feed-forward lessons live modelling is being used rather than pre-prepared models.

- More prepared models are created in advance of assessment points as guidelines/reference tools for students.

- Prepared models are used after formal assessment as a comparison for students to use when self- or peer-assessing their performance.

- The specific focus in the feed-forward sheets on SPaG has been a helpful reminder to utilise micro-moments in lessons to consolidate technical skills.

- The teacher uses a ‘Students of Concern’ section (not visible to students) to provide additional support and interventions and to reflect on the success of any previous intervention.

- ‘Closing the Loop’ books have been introduced and have become a powerful tool in improving the value of assessment as a teaching and learning experience. These use a template for whole-class feedback and enable teachers to keep a track record of assessments and a track of their intentions in terms of adaptations to teaching as a result of assessment information about students’ knowledge, understanding and progress.

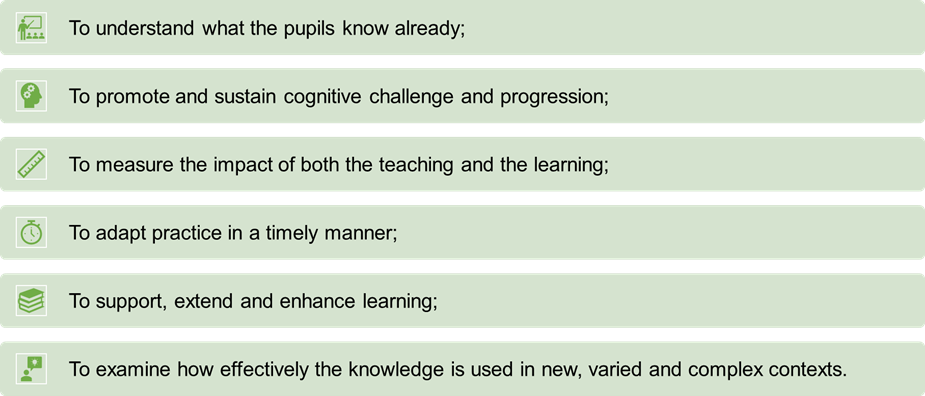

This is an example of assessment which is increasing the teacher’s criticality of the teaching and learning process and their expertise within this. The pupils benefit from the focused response to their work and the modelled practice. This exemplifies aspects of assessment used to achieve high-quality teaching:

“Rethinking assessment” across the NACE community

Other NACE member schools shared their experiences, including:

- A focus on understanding personal development – considering ways in which pupils’ overall experience and development can be better understood and supported, as part of assessment.

- Retrieval introduced as a core and explicit part of lesson sequences and schemes of work.

- The use of science practical activities linked to examination questions, to expose pupils to desirable difficulties. These reveal pupils’ knowledge and skills; support development and progress; and provide information needed to scaffold support at an individual level.

- Changes to reporting introduced to empower pupils, as well as informing leaders, teachers and parents.

- Developing the use of Rosenshine’s principles with a focus on higher-order questioning; this challenges more able pupils to think more deeply, extends their thinking, and has demonstrable benefits for other pupils in a mixed ability classroom.

- Models of excellence shared with pupils.

- Use of film resources and extended book study to encourage critical thinking and application of skills.

These varied approaches to assessment reflect the different contexts in which teachers work. They include assessment being used in three distinct ways:

Each of these has a place within teaching and learning. It is important that each type of assessment has a clear purpose and will impact effectively on the quality of teaching and the depth of learning. Pupils need to develop both within and beyond the content constraints of a curriculum. They need to learn about concepts as well as content. They need to understand what they are learning and how it links to other areas of learning. They need to develop cognition and cognitive strategies so that their learning is more useful to them both within school and in life.

The greatest gains can be achieved when the assessment itself is a part of learning and pupils have greater ownership of the process. As assessment practices develop within schools, the aim should be to upskill pupils so that they have the information they need to become self-regulating and to develop metacognitively.

Key factors for successful implementation

During the meetup, we observed that the schools with well-established assessment practice have introduced this within a whole-school ethos and strategy. Staff and pupils have a shared understanding of the use, purpose and benefits of the practice. Middle leaders are influential in the development of strategy, its consistency and the successful use within a subject specific context. Pupils are at the heart of the model and interact with assessment and feedback to improve their own learning. They develop cognitively and understand their own thinking and learning.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective assessment practices – including new initiatives, and well-established practices.

You may feel that some of the examples cited above are similar to practices in your own school, or you may have well-developed assessment models that would be of interest to others. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- Which area of assessment is used most effectively?

- What assessment practices are having the greatest impact on learning?

- How do teachers and pupils use the assessment information?

- How do you develop an understanding of pupils’ overall development?

- How do you use assessment information to provide wider experience and developmental opportunities?

- Is assessment developing metacognition and self-regulation?

Read more:

Plus: NACE is partnering with The Brilliant Club on a webinar exploring the links between metacognition and assessment, featuring practical examples from NACE member schools. Details coming soon – check our webinars page.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

collaboration

feedback

metacognition

pedagogy

progression

research

Permalink

| Comments (1)

|

|

Posted By Kirstin Mulholland,

15 February 2022

|

Dr Kirstin Mulholland, Content Specialist for Mathematics at the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), shares a metacognitive strategy she’s found particularly helpful in supporting – and challenging – the thinking of higher-attaining pupils: “the debrief”.

Why is metacognition important?

Research tells us that metacognition and self-regulated learning have the potential to significantly benefit pupils’ academic outcomes. The updated EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit has compiled well over 200 school-based studies that reveal a positive average impact of around seven months progress. But it also recognises that "it can be difficult to realise this impact in practice as such methods require pupils to take greater responsibility for their learning and develop their understanding of what is required to succeed” .

Approaches to metacognition are often designed to give pupils a repertoire of strategies to choose from, and the skills to select the most suitable strategy for a given learning task. For high prior attaining pupils, this offers constructive and creative opportunities to further develop their knowledge and skills.

How can we develop metacognition in the classroom?

In my own classroom, a metacognitive strategy which I’ve found particularly helpful in supporting – and, crucially, challenging – the thinking of higher-attaining pupils is “the debrief”. The debrief as an effective learning strategy links to Recommendation 1 of the EEF’s Metacognition and Self-regulated Learning Guidance Report (2018), which highlights the importance of encouraging pupils to plan, monitor and evaluate their learning.

In a debrief, the role of the teacher is to support pupils to engage in “structured reflection”, using questioning to prompt learners to articulate their thinking, and to explicitly identify and evaluate the approaches used. These questions support and encourage pupils to reflect on the success of the strategies they used, consider how these could be used more effectively, and to identify other scenarios in which these could be useful.

Why does this matter for higher-attaining pupils?

When working in my own primary classroom, I found that encouraging higher-attaining pupils to explicitly consider their learning strategies in this way provides an additional challenge. Initially, many of the pupils I’ve worked with have been reluctant to slow down to consider the strategies they’ve used or “how they know”. Some have been overly focused on speed or always “getting things right” as an indication of success in learning.

When I first introduced the debrief into my own classroom, common responses from higher-attaining pupils were “I just knew” or “It was in my head”. However, what I also experienced was that, for some of these pupils, because they were used to quickly grasping new concepts as they were introduced, they didn’t always develop the strategies they needed for when learning was more challenging. This meant that, when faced with a task where they didn’t “just know”, some children lacked resilience or the strategies they needed to break into a problem and identify the steps needed to work through this.

As I incorporated the debrief more and more frequently into my lessons, I saw a significant shift. Through my questioning, I prompted children to reflect on the rationale underpinning the strategies they used. They were also able to hear the explanations given by others, developing their understanding of the range of options available to them. This helped to broaden their repertoire of knowledge and skills about how to be an effective learner.

How does the debrief work in practice?

Many of the questions we can use during the debrief prompt learners to reflect on the “what” and the “why” of the strategies they employed during a given task. For example,

- What exactly did you do? Why?

- What worked well? Why?

- What was challenging? Why?

- Is there a better way to…?

- What changes would you make to…? Why?

However, I also love asking pupils much more open questions such as “What have you learned about yourself and your learning?” The responses of the learners I work with have often astounded me! They have encompassed not just their understanding of the specific learning objectives identified for a given lesson, but also demonstrating pupils’ ability to make links across subjects and to prior learning. This has led to wider reflections about their metacognition – strengths or weaknesses specific to them, the tasks they encountered, or the strategies they had used – or their ability to effectively collaborate with others.

For me, the debrief provides an opportunity for pupils’ learning to really take flight. This is where reflections about learning move beyond the boundaries and limitations of a single lesson, and instead empower learners to consider the implications of this for their future learning.

For our higher-attaining pupils, this means enabling them to take increasing ownership over their learning, including how to do this ever more effectively. This independence and control is a vital step in becoming resilient, motivated and autonomous learners, which sets them up for even greater success in the future.

References

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

language

maths

metacognition

pedagogy

problem-solving

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

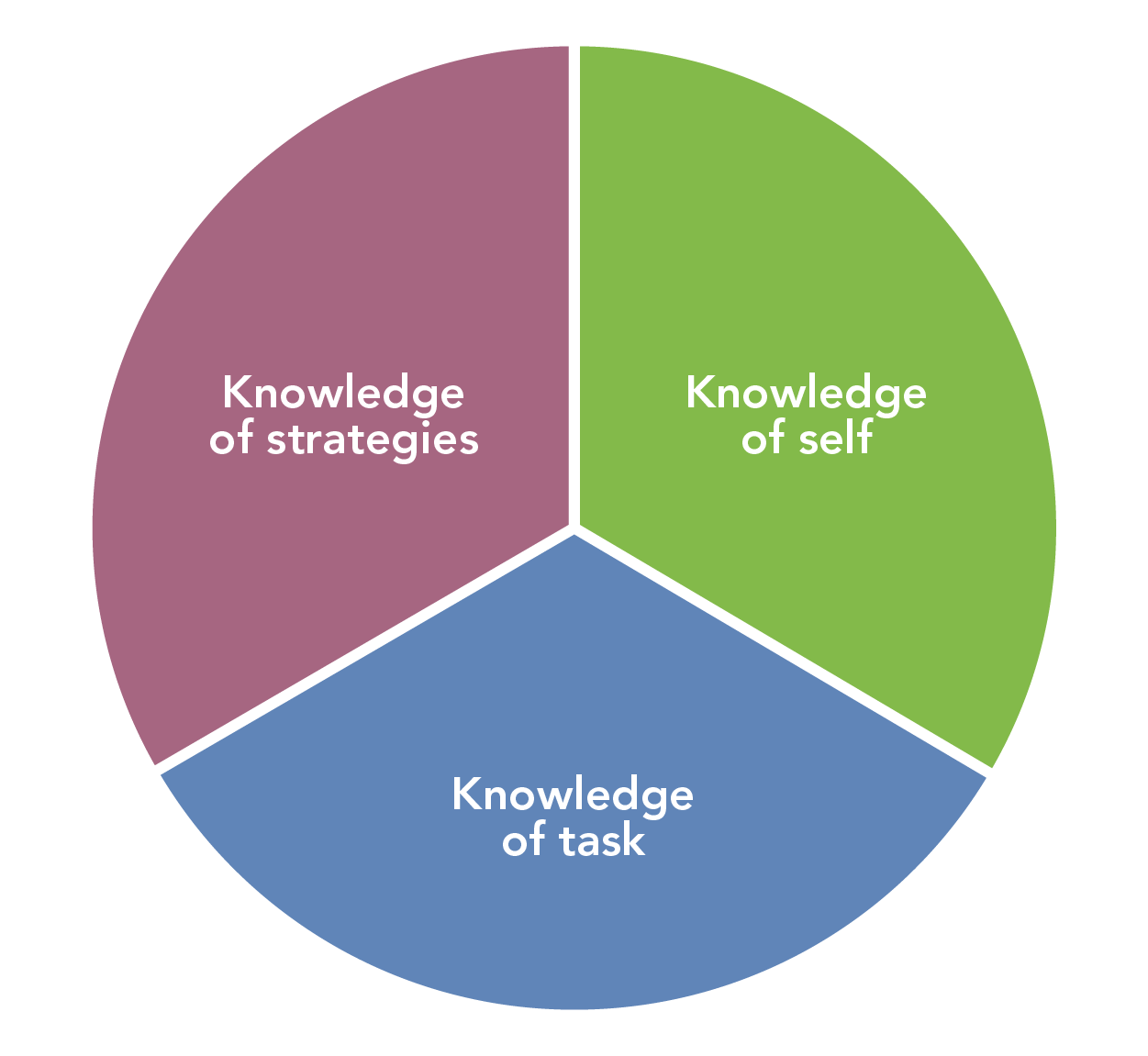

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ems Lord,

11 February 2022

|

Dr Ems Lord, Director of the University of Cambridge’s NRICH initiative, shares three activities to try in your classroom, to help learners improve their use of mathematical vocabulary.

Like many academic subjects, mathematics has developed its own language. Sometimes this can lead to humorous clashes when mathematicians meet the real world. After all, when we’re calculating the “mean”, we’re not usually referring to a measurement of perceived nastiness (unless it’s the person who devised the problem we’re trying to solve!).

Precision in our use of language within mathematics does matter, even among school-aged learners. In my experience, issues frequently arise in geometry sessions when working with pyramids and prisms, squares and rectangles, and cones and cylinders. You probably have your own examples too, both within geometry and the wider curriculum.

In this blog post, I’ll explore three tried-and-tested ways to improve the use of mathematical vocabulary in the classroom.

1. Introduce your class to Whisper Maths

“Prisms are for naughty people, and pyramids are for dead people.” Even though I’ve heard that playground “definition” of prisms and pyramids many times before, it never fails to make me smile. It’s clear that the meanings of both terms cause considerable confusion in KS2 and KS3 classrooms. Don’t forget, learners often encounter both prisms and pyramids at around the same time in their schooling, and the two words do look very similar.

One useful strategy I’ve found is using an approach I like to refer to as Whisper Maths; it’s an approach which allows individuals time to think about a problem before discussing it in pairs, and then with the wider group. For Whisper Maths sessions focusing on definitions, I tend to initially restrict learner access to resources, apart from a large sheet of shared paper on their desks; this allows them to sketch their ideas and their drawings can support their discussions with others.

This approach helps me to better understand their current thinking about “prismness” and “pyramidness” before moving on to address any misconceptions. Often, I’ve found that learners tend to base their arguments on their knowledge of square-based pyramids which they’ve encountered elsewhere in history lessons and on TV. A visit to a well-stocked 3D shapes cupboard will enable them to explore a wider range of examples of pyramids and support them to refine their initial definition.

I do enjoy it when they become more curious about pyramids, and begin to wonder how many sides a pyramid might have, because this conversation can then segue nicely into the wonderful world of cones!

2. Explore some family trees

Let’s move on to think about the “Is a square a rectangle?” debate. I’ve come across this question many times, and similarly worded ones too.

As someone who comes from a family which talks about “oblongs”, I only came across the “Is a square a rectangle?” debate when I became a teacher trainer. For me, using the term oblong meant that my understanding of what it means to be a square or an oblong was clear; at primary school I thought about oblongs as “stretched” squares. This early understanding made it fairly easy for me to see both squares and oblongs (or non-squares!) as both falling within the wider family of rectangles. Clearly this is not the case for everyone, so having a strategy to handle the confusion can be helpful.

Although getting out the 2D shape box can help here, I prefer to sketch the “family tree” of rectangles, squares and oblongs. As with all family trees, it can lead to some interesting questions when learners begin to populate it with other members of the family, such the relationship between rectangles and parallelograms.

3. Challenge the dictionary!

When my classes have arrived at a definition, it’s time to pull out the dictionaries and play “Class V dictionary”. To win points, class members need to match their key vocabulary to the wording in the dictionary. For the “squares and rectangles” debate, I might ask them to complete the sentence “A rectangle has...”. Suppose they write “four sides and four right angles”, we would remove any non-mathematical words, so it now reads “four sides, four right angles.” Then we compare their definition with the mathematics dictionary.

They win 10 points for each identical word or phrase, so “four right angles, four sides” would earn them 20 points. It’s great fun, and well worth trying out if you feel your classes might be using their mathematical language a little less imprecisely than you would like.

More free maths activities and resources from NRICH…

A collaborative initiative run by the Faculties of Mathematics and Education at the University of Cambridge, NRICH provides thousands of free online mathematics resources for ages 3 to 18, covering early years, primary, secondary and post-16 education – completely free and available to all.

The NRICH team regularly challenges learners to submit solutions to “live” problems, choosing a selection of submissions for publication. Get started with the current live problems for primary students, live problems for secondary students, and live problems for post-16 students.

Tags:

free resources

language

maths

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

problem-solving

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

08 November 2021

|

The opportunities that present themselves to teachers these days are truly amazing. Last summer the chance to write and deliver a Zoom-based programme of learning to primary-aged pupils in Beijing was presented to me. Yes, Beijing. How could I refuse the opportunity to apply an English teaching style to another culture? Through a partnership between NACE and a private educational provider I embarked upon a programme of 16 two-hour sessions over a period of eight weeks via Zoom, using Google Classroom for resources and homework. The lessons were taught from 7-9pm 9pm Beijing time. Would my teaching keep the nine-year olds awake on a Sunday night?

The context

The education company I worked with offers what it terms ‘gifted and talented programmes’ to all ages and across the curriculum. The pupils mainly attended international schools and had their school lessons taught in English. The programmes have previously been delivered in person during the summer holidays by overseas teachers, primarily from the US. A move to Zoom-based learning after the pandemic has proved successful and now lessons are offered throughout the year in the evening and at the weekend with parents paying highly for the courses. The company organised the programme very well with training and support for the teacher at every stage. It is an impressive operation.

I taught an English literature unit based upon a comparative novel study using ‘The Iron Man’ and ‘The Giant’s Necklace’ – texts familiar to many Key Stage 2 teachers. The pupils worked hard in lessons, listened well and thought deeply. They retained knowledge well and I used retrieval practice at the start of most lessons. They completed these tasks eagerly. They were a pleasure to teach. Off-task behaviour was rare, pupils laughed when jokes were made – though of course humour was lost in translation at times (or maybe my jokes were not funny).

What worked?

Central to the learning was the pupils reading aloud. They loved this. It gave me the chance to clarify meaning, check vocabulary and asks questions at depth. All pupils read, some with impressive fluency given it was their second language. Parents commented they were not used to working this way. I think in other courses they often read for homework and then in lessons answered questions at length and then wrote essays. Despite being young there is an emphasis on academic writing. One pupil referred to his story as an essay, revealing that writing a story was unusual for his studies. Writing the story was a highlight for the pupils, one I suspect they are not used to. The reading also allowed for targeted questions, which the parents seemed to like, having not seen the technique used before. Yes, parents often sat next to their child, out of my eyesight, to help if needed. Hearing them whisper what to say on occasion was a new one for me.

To get an idea of the dedication of the pupils and support of the parents, it is worth mentioning that one pupil joined the lesson while travelling home on a train from her holiday. With her mum sat next to her, she joined in the lesson as best she could and all with a smile on her face. Another pupil said her father had asked her how she was reviewing the learning from the previous lesson each week. Learning is valued. Technical difficulties were rare but when they arose the pupils were proactive in overcoming difficulties, moving rooms and logging on with another device. Resilience and self-regulation was noticeably high. The last lesson included a five-minute presentation from each pupil on what they had learned from the unit. Pupils prepared well, the standard was high and pupils showed depth of understanding of the themes covered.

Addressing the language gap

As a teacher the main challenge to emerge was the gap between the pupils’ understanding of complex literary concepts and the use of basic English. The units are aimed at what is termed ‘gifted and talented’ yet at times I needed to cover areas such as verb tenses at a basic level. In English assessment terms the students were at times working at Year 6 greater depth for reading and some aspects of their writing, but were only ‘working towards’ in other areas.

I have decades of experience teaching EAL learners, the majority of whom attained at or above national expectation at the end of Key Stage 2 despite early language challenges. Here the gap was even more pronounced. Should I focus on the higher-order thinking and ignore what was essentially a language issue? I decided not to do that since the students need to develop all aspects of their English to better express their ideas, including writing. I did mini-grammar lessons in context, worked primarily on verb tenses in their writing and when speaking, and prioritised Tier 2 vocabulary since Tier 3 specialist vocabulary was often strong. They knew what onomatopoeia was, but not what a plough was, let alone cultural references like a pasty. Why would they?

Motivations and barriers

At the start of each lesson, I welcomed each pupil personally and asked them, ‘What have you been doing today?’ Almost every answer referred to learning or classes. They had either completed other online lessons, swimming lessons, fencing lessons, piano practice (often two hours plus) or other planned activities. Rarely did a pupil say something like ‘I rode my bike’. Having a growth mindset was evident and the students understood this and displayed admirable resilience. Metacognition and self-regulation were also evident in learning.

However, one area where the pupil did struggle was in self-assessment. The US system is based on awarding marks and grades regularly, including for homework. I chose not to do this, thinking grades for homework would be somewhat arbitrarily awarded unless something like a 10-question model was used weekly. The research on feedback without grades suggests that it leads to greater pupil progress and this was my focus. It would be interesting to explore with the students whether my lack of grade awarding lowered their motivation because they were used to extrinsic rather than intrinsic motivation. Does this contradict my assertion that growth mindset was strong?

Another issue emerged linked to this – that of perfectionism. One pupil was keen to show her knowledge in lessons but was the only pupil who rarely submitted homework. A large part of the programme was to write a story based on ‘The Iron Man’, which this student did not seem to engage with. At the parents’ meeting the mother asked if she could write for her child if it was dictated, a suggestion I rejected saying the pupil needed to write so that I could provide feedback to improve. It became clear the child did not want to submit her work because it was ‘not as good as their reading’. The child had told me in the first lesson that they had been accelerated by a year at school. I fear problems are being stored up that my gentle challenges have only now begun to confront and that may take a long time to resolve. This was not the case for the other pupils, but the idea of pressure to work hard and succeed was always evident. I realise the word ‘pressure’ here is mine and may not be used by others in the same context, including the parents.

Parental support

So, what of parental engagement? The first session began with getting-to-know-each-other activities and a discussion on reading. After 20 minutes the TA messaged me to say the parent of one pupil felt the lesson was ‘too easy’. Nothing like live feedback! I messaged back that the aim at that point was to relax the children and build a teaching relationship. A few weeks later the same parent asked to speak to me at the end of the lesson. I was prepared for a challenge that did not materialise. She said her child liked the lessons and she loved the way I asked personalised questions to extend her child. She was not used to her being taught this way. I used a mixture of cold-calling, named lolly-sticks in a pot and targeted questions, which seemed novel and the children loved.

Parent meetings were held half-way through the unit and feedback about things like the questioning wasvery positive. The extremely upbeat response was surprising since the teaching seemed a little ‘flat’ to me given the limitations of Zoom but that is not how it was received. The pupils seemed to enjoy the variety of pace, the high level of personal attention, the range of tasks, the chunking of the learning and the sense of fun I tried to create. Parents asked when I was delivering a new course and wanted to know when I was teaching again.

Final reflections

So, what did I learn? Children are children the world over, which we all know deep down. But these children apply themselves totally to their work. They expect to work hard and enjoy ‘knowing’ things. Their days are filled with activity and learning. Zoom can work well but still the much-prized verbal feedback is not the same from 5,000 miles away.

And finally, as a teacher I have learned over the years to be professional and to keep teaching whatever happens. When a pupil said they didn’t finish their homework because they were traveling back home, I enquired where they had been. ‘Wuhan’ they replied. Without missing a beat, I further asked, ‘So what do you think about the plot in chapter two then?’

Would you be interested in sharing your experiences of teaching remotely and/or across cultures? Is this an area you’d like to explore or develop? Contact communications@nace.co.uk to share your experience or cpd@nace.co.uk to express your interest in being part of future projects like this.

Tags:

feedback

language

literature

lockdown

mindset

motivation

parents and carers

pedagogy

perfectionism

questioning

remote learning

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

08 March 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Curriculum Development Director and former CEO of Portswood Primary Academy Trust

“I once estimated that, if you price teachers’ time appropriately, in England we spend about two and a half billion pounds a year on feedback and it has almost no effect on student achievement.”

– Dylan Wiliam

So why do we do it? Primarily because the EEF toolkit identified feedback as one of the key elements of teaching that has the greatest impact. With this came the unintended consequence of an Ofsted handbook and inspection reports that criticised a lack of written feedback and response to pupils’ responses to marking which led to what became an unending dialogue with dangerous workload issues. At some point triple-marking seemed more about showing a senior leader or external inspector that the dialogue had happened. More recently, the 2016 report of the Independent Teacher Workload Review Group noted that written marking had become unnecessarily burdensome for teachers and recommended that all marking should be driven by professional judgement and be “meaningful, manageable and motivating”.

So what is “meaningful, manageable and motivating” in terms of marking and feedback for more able learners? Is it about techniques or perhaps more a question of style? At Portswood Primary Academy Trust our feedback has always been as close to the point of teaching as possible. It centres on real-time feedback for pupils to respond to within the lesson. Paul Black was kind enough to describe it as “marvellous” when he visited, so not surprisingly this is what we have stuck with. Teachers work hard in lessons to give this real-time feedback to shape learning in the lesson. The importance of this approach is that feedback is instant, feedback is relevant, and feedback allows pupils to make learning choices (EEF marking review 2016). But is there more to it for more able learners?

Getting the balance right

In giving feedback to more able learners the quality of questioning is crucial. This should aim to develop the higher-order skills of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analysing, evaluating and creating). A more facilitative approach should develop thinking. The questions should stimulate thought, be open, and may lead in unexpected directions.

A challenge for all teachers is how to balance feeding back to the range of attainment in a class. The recent Ofsted emphasis on pupils progressing through the programmes at the same rate is not always the reality for teachers. Curriculum demands are higher in core subjects, meaning teachers are under pressure to ensure most pupils achieve age-related expectations (ARE). The focus therefore tends to be more on pupils below ARE, with more time and effort focused there. The demands related to SEND pupils can also mean less teacher time devoted to more able pupils who have already met the standards.

Given that teachers may have less time for more able learners it is vital the time is used efficiently. For the more able it is less about the pupils getting the right answer, and more about getting them to ask the right questions. Detailed feedback in every lesson is unlikely so teachers should:

- Look at the week/unit as a whole to see when more detailed focus is timely;

- Use pre-teaching (such as in assembly times) to set up more extended tasks;

- Develop pupils’ independence and resilience to ensure there is not an over-reliance on the teacher;

- Identify times in lessons to provide constructive feedback to the more able group that would have the most impact.

Another tension for teachers is the relationship between assessment frameworks and creativity. For instance, at KS1 and KS2, the assessment criteria at greater depth in writing is often focused on technical aspects of writing. But is this stifling creativity? Is the reduction in students taking A-level English because of the greater emphasis on the technical at GCSE? As one able Year 10 writer commented, “Why do I have to focus on semicolons so much? Writing comes from the heart.” Of course the precise use of semicolons can aid writing effectively from the heart, but if the passion is dampened by narrow technical feedback will the more able child be inspired to write, paint or create? Teachers need to reflect on what they want to achieve with their most able learners.

Three guiding principles

So what should the guiding principles for feedback to more able learners be? Three guiding principles for teachers to think about are:

1. Ownership with responsibility

More able learners need to take more ownership of their work; with this comes responsibility for the quality of their work. Self-marking of procedural work and work that has a definitive answer (the self-secretary idea) allows for children to:

- Check – “Have I got it?”

- Error identify – “I haven’t got it; here's why”

- Self-select to extend – “What will I choose to do next?”

Only the last of these provides challenge. The first two require responsibility from learners for the fundamentals. The third leads to more ownership for pupils to take their learning further. The teacher could aid this self-selection or only provide feedback once a course of action is taken. Here the teacher is nudging and guiding but not dictating with their feedback.

2. Developing peer assessment

There is a danger that peer assessment can be at a low level so the goal is developing a more advanced level of dialogue about the effectiveness of outcomes and how taking different approaches may lead to better outcomes or more efficient practice. For instance, peer feedback allows for emotional responses in art/design/computing work – “Your work made me feel...”; “This piece is more effective because...”. For some more able pupils not all feedback is welcome, whether from peers or teachers. The idea that I can reject your feedback here is important: “Can you imagine saying to Dali that his landscapes are good but he needs to work on how he draws his clocks?”

3. Being selective with feedback

The highly skilled teacher will, at times, decide not to give feedback, at least not straight away. They are selective in their feedback. If you jump in too quickly, it can stop thinking and creativity. It can eliminate the time to process and discover. It can also be extremely annoying for the learner!

In practical terms this means letting them write in English and giving feedback later, not while they are in the flow. In a mathematical/scientific/humanities investigative setting, let them have a go and ask the pertinent question later, perhaps when they encounter difficulty. This question will be open and may nudge rather than direct the pupils. It might not be towards your intended outcome but should allow for them to take their learning forward, perhaps in unexpected directions.

In summary, this gets to the heart of the difference in feedback for more able learners compared to other pupils. While the feedback will inevitably have higher-level subject content, it should also:

- Emphasise greater responsivity for the pupil in their learning

- Involve suggestion, what ifs and hints rather than direction, and…

- Seek to excite and inspire to occasionally achieve the fantastic outcome that a more rigid approach to feedback never would. They may even write from the heart.

What does this look like in practice?

Jeavon Leonard, Vice Principal at Portswood Primary School, outlines a personal approach for more able learners he has used: “Think about when we see a puzzle in a paper/magazine – if we get stuck (as adults) we tend to flip to the answer section, not to gain the answer alone but to see how the answer was reached or fits into the clues that were given. This in turn leads to a new frame of skills to apply when you see the next problem. If this is our adult approach, why would it not be an effective approach for pupils? The feedback is in the answer. Some of the theory for this is highlighted in Why Don't Students Like School? by Daniel Willingham.”

Mel Butt, NRICH ambassador and Year 6 teacher at Tanners Brook Primary, models the writing process for her more able learners including her own second (and third) drafts which include her ‘Think Pink’ improvement and corrections. While this could be used for all pupils, Mel adds the specific requirements into the improved models for more able learners based on the assessment requirement framework for greater depth writing at the end of Key Stage 2. She comments: “I would also add something extra that is specific to the cohort of children based on the needs of their writing. We do talk about the criteria and the process encourages independence too. It's also good for them to see that even their teachers as writers need to make improvements.” The feedback therefore comes in the form of what the pupils need to see based on what they initially wrote.

Further reading

From the NACE blog:

Additional support

Dr Keith Watson is presenting a webinar on feedback on Friday 19 March 2021, as part of our Lunch & Learn series. Join the session live (with opportunity for Q&A) or purchase the recording to view in your own time and to support school/department CPD on feedback. Live and on-demand participants will also receive an accompanying information sheet, providing an overview of the research on effective feedback, frequently asked questions, and guidance on applications for more able learners. Find out more.

Tags:

assessment

differentiation

feedback

metacognition

pedagogy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

27 January 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Associate

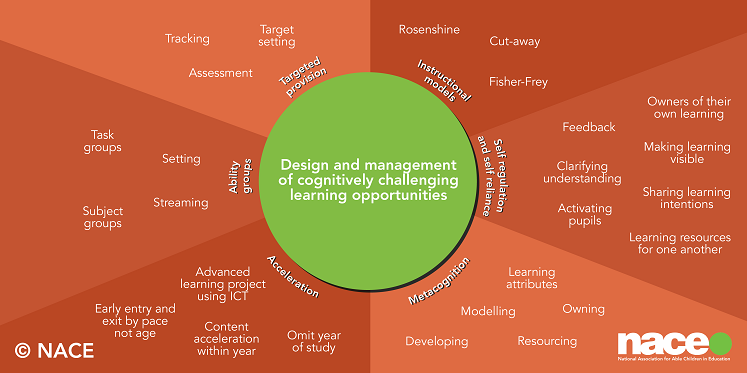

In recent years many new developments in teaching have been most welcome and have helped the shift towards a more research-informed profession. NACE’s recent report Making space for able learners – Cognitive challenge: principles into practice provides examples of strategies used for the design and management of cognitively challenging learning opportunities, including reference to Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction (2010) which outline many of these strategies.

These principles of instruction are particularly influential in current teaching, which is pleasing to the many good teachers who have been used them for years, although they may not have attached that exact language to what they were doing. These principles are especially helpful for early career teachers, but like all principles they need to be constantly reflected upon. I was always taken by Professor Deborah Eyre’s reference to “structured tinkering” (2002): not wholesale change but building upon key principles and existing practice.

This is where “cutaway” comes in – another of the strategies identified in the NACE report, and one which I would like to encourage you to “tinker” with in your approach to ability grouping and ensuring appropriately challenging learning for all.

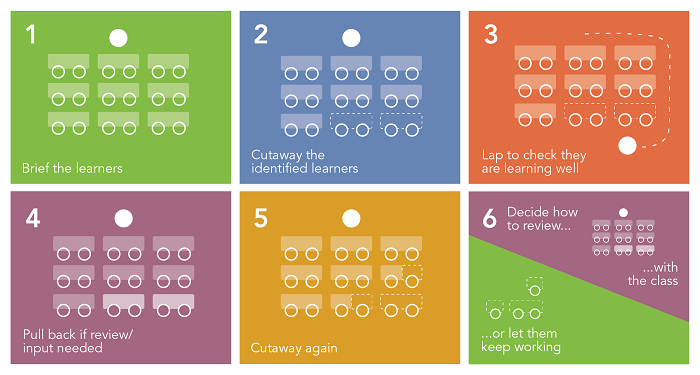

What is “cutaway” and why use it?

The “cutaway” approach involves setting high-attaining students off to start their independent work earlier than the vast majority of the class, while the teacher continues to provide direct instruction/ modelling to the main group. In this way the high attainers can begin their independent work more quickly and can avoid being bored by the whole class instruction which they can find too easy, even when the teacher is trying to “teach to the top”. Once the rest of the class has begun their independent work, the teacher can then focus on the higher attaining group to consolidate the independent work and extend them further.

There are more nuances which I will explain later, but you may wonder, how did this way of working come about?

An often-quoted figure from the National Academy of Gifted and Talented Youth (NAGTY) was that gifted students may already have acquired knowledge of 40-50% of their lessons before they are taught. If I am honest, this was 100% in some of my old lessons! With whole class teaching, retrieval practice tasks and modelling (all essential elements in a lesson), there are clear dangers of pupils being asked to work on things they already know well. There is the issue of what Freeman, (quoted in Ofsted, 2005:3), called the “three-time problem” where: “Pupils who absorb the information the first time develop a technique of mentally switching off for the second and the third, then switching on again for the next new point, involving considerable mental skill.” Why waste this time?

The idea of “cutaway” was consolidated when I carried out a research project involving the use of learning logs to improve teaching provision for more able learners (Watson, 2005). In this project teachers adapted their teaching based on pupil feedback. The teachers realised that, in a primary classroom, keeping the pupils too long “on the carpet” was inappropriate and the length of time available to work at a high level was being minimised. One of the teachers reflected: “Sometimes during shared work on the carpet, when revising work from previous lessons to check the understanding of other pupils, I feel aware of the more able children wanting to move on straight away and find it difficult to balance the needs of all the children within the Year 5 class.”

It therefore became common in lessons (though not all lessons) to cutaway pupils when they were ready to begin independent work. By using “cutaway” the pupils use time more effectively, develop greater independence, can move through work more quickly and carry out more extended and more challenging tasks. The method was commented upon favourably during a HMI inspection that my school received and has ever since been a mainstay of teaching at the school.

Who, when and how to cutaway

So how does a teacher decide when and who to cutaway? The method is not needed in all lessons, the cutaway group should vary based upon AfL, and at its best it involves pupils deciding whether they feel they need more modelling/explanation from the teacher or are ready to be cutaway. In a recent NACE blogpost on ability grouping, Dr Ann McCarthy emphasises that in using cutaway “the teacher constantly assesses pupils’ learning and needs and directs their learning to maximise opportunities, growth and development” and pupils “leave and join the shared learning community”. This underlines the importance of the AfL nature of the strategy and the importance of developing learners’ metacognition, which was another key finding in the NACE report.