Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Tom Greenwood,

26 March 2025

|

Holme Grange School's Tom Greenwood shares six steps to maximise the impact of your practical science lessons.

Science is more than just memorising facts and following instructions. True scientific thinking requires critical analysis, problem-solving, and creativity. Practical science provides the perfect platform for developing these skills, pushing students beyond basic understanding and into the realm of higher-order thinking.

Why challenge matters in science education

Practical science sits at the peak of Bloom’s revised taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), requiring students not just to remember and understand but to apply, analyse, evaluate, and create. These skills are essential for developing scientifically literate individuals who can tackle real-world problems with confidence and insight.

Steps to maximizing the impact of practical science

To truly challenge students and develop their higher-order thinking, practical science lessons must be carefully structured. Here’s how:

Step 1: Solve real-world problems

Practical science activities should be grounded in real-world applications. When students see the relevance of their experiments, their engagement increases. For example, testing water purity or designing a simple renewable energy system connects scientific principles to everyday life.

Step 2: Get the groups right

Collaboration is key in scientific exploration. Thoughtful grouping of students – pairing diverse skill levels or encouraging peer mentoring – can enhance problem-solving and communication skills.

Step 3: Maintain a relentless focus on variables

From Year 5 to Year 11, students should develop a keen understanding of variables. This means recognising independent, dependent, and control variables and understanding their importance in experimental design.

Step 4a: Leave out a variable

By removing a key variable from an experiment, students are forced to think critically about the design and purpose of their investigation. They must determine what’s missing and how it affects the outcome.

Step 4b: Omit the plan

Instead of providing a step-by-step method, challenge students to devise their own experimental plans. This pushes them to apply their understanding of scientific concepts and fosters creativity in problem-solving.

Step 5: Analyse data like a pro

Teaching students to collect, visualise, and interpret data is crucial. Using AI tools to display class results can make data analysis more engaging and accessible. By linking their findings back to the research question, students develop deeper analytical skills.

Step 6: When practicals go wrong (or right!)

Failure is an integral part of scientific discovery. Encouraging students to reflect on unexpected results – whether positive or negative – teaches resilience, adaptability, and critical thinking.

Bonus step: Harness the power of a Science Challenge Club

A Science Challenge Club can provide a platform for students to explore scientific questions beyond the curriculum. Such clubs foster independent thinking and offer opportunities for students to work on long-term investigative projects, deepening their understanding and enthusiasm for science.

Final thoughts: why practical science is essential

Engaging students in hands-on science doesn’t just make lessons more interesting – it equips them with crucial skills:

- Critical thinking: encourages deeper questioning and problem-solving.

- Collaboration: strengthens teamwork and communication.

- Real-world problem solving: helps students connect theory to practice.

As educators, we can design activities that challenge high-achieving students, encourage independent experiment design, and foster strong analytical skills. By doing so, we prepare students not only for exams but for real-world scientific challenges.

The future of science lies in the hands of the next generation. Let’s ensure they have the skills to think critically, innovate boldly, and explore fearlessly.

Related reading and resources:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

collaboration

critical thinking

pedagogy

problem-solving

resilience

science

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By James Croxton-Cayzer,

26 March 2025

|

Walton Priory Middle School’s James Croxton-Cayzer shares his top tips for ensuring practical science lessons get students thinking as well as doing.

"Sir, are we doing a practical today?"

If you teach science, you probably hear this question at least once a lesson. Pupils love practical work, but how often do we stop and ask ourselves: are they really learning from it? Are practicals just a fun way to prove a theory, or can they be something deeper – something that engages students intellectually as well as physically?

I was recently asked to speak at a NACE member meetup about how we at Walton Priory Middle School ensure that practicals are not just hands-on, but minds-on as well. Here’s how we approach it.

1. Don’t just do a practical: know why

Before anything else, ask yourself: What do I want my pupils to learn? Every practical should have a clear learning goal, whether that’s substantive knowledge (e.g. learning about the planets) or disciplinary knowledge (e.g. “How are we going to find out the RPM of a propeller?”).

I used to assume that if pupils were engaged, they were learning. But engagement isn’t the same as deep thinking. By clearly defining why we are doing a practical and keeping cognitive overload in check, pupils can focus on the right aspects of the lesson.

2. Give them a puzzle to solve

Rather than handing over all the information at once, I break lessons into two parts:

- Knowledge I am going to give them

- Knowledge I want them to discover for themselves

Children love discovery. Instead of telling them everything, create opportunities for them to piece it together themselves. If you’re like I was, you might worry about withholding information in case they never figure it out. But I’ve found that knowledge earned is usually better retained and understood than knowledge simply given.

For example, when teaching voltage in Year 6, I might tell them that increasing voltage will increase the speed of a motor (since there’s little mystery there). But I won’t tell them how to measure the speed of the motor. Instead, I challenge them: “What methods could we use to measure the speed of a fan?” This immediately shifts their thinking from passive reception to active problem-solving.

3. Hook them with a story

While linking science to real-world applications is common practice, storytelling as a teaching tool is often overlooked. A compelling story can make abstract scientific concepts feel personal and meaningful.

For example, in our Year 5 Solar System topic, I frame the lessons as a journey where alien explorers (who conveniently share my students' names – weird that…) must learn all they can about our planet and surroundings. In our Properties of Materials topic, I create audiologs for each lesson of a ship’s journey – except there’s a saboteur on board! Each lesson, the rogue does something that requires students to investigate different properties to solve the problem. Will they ever find out who did it? Who knows! But they are certainly engaged and thinking about the science.

4. Use partial information to encourage scientific thinking

One of the most powerful ways to keep students engaged is to avoid giving them everything upfront. Instead, drip-feed key information and let them work out the missing pieces.

For example, instead of just listing the planets, I provide partial information – snippets of data they must organise themselves to determine planetary order. This encourages effortful retrieval and intellectual engagement, rather than passive memorisation.

Returning to our Year 6 voltage lesson, I ask: “How can we prove that?” Some students count propeller rotations manually. Others try using a strobe light or a slow-motion camera. One of my class recently attached a lollipop stick to the fan and tried to count the clicks on a piece of paper – a great idea, but the clicks were too fast! So I turned it back on them: “How do we solve this?”

- Record the sound? Great!

- Slow it down? Super!

- Put the sound file in Audacity and count the visualised sound wave for two seconds, then multiply by thirty? Amazing!

The key is that they think like scientists – testing, adapting, and refining their approach.

5. Keep everyone engaged

Minds-on practicals require careful structuring. Not all students will approach a task in the same way, so scaffolding and adaptive teaching are key:

- Structured worksheets help those who struggle with open-ended tasks.

- Flexible questioning allows you to stretch more able learners without overwhelming others.

- Pre-discussion before practicals ensures students understand the why as well as the how.

All students, including those with additional needs, should feel part of the investigation. Clear step-by-step instructions, visual aids, and breaking down the task into smaller chunks make a big difference.

Even with the best planning, some students will struggle. Here’s what I do:

- Encourage peer teaching. Can a more confident pupil explain the method?

- Break it down even further. Can we isolate just one variable to focus on?

- Provide alternative ways to engage. If a pupil is overwhelmed, can they observe and record data instead? Once they feel comfortable, they may ask to take on a more active role.

- Reframe the challenge. Instead of “You’re wrong,” or “That won’t work,” ask, “What made you think that?” This builds resilience and scientific thinking.

Key takeaways

- Make sure every practical has a clear learning goal.

- Give pupils a reason to investigate, not just instructions to follow.

- Use partial information to make them think like scientists.

- Ensure adaptive teaching so all pupils can access the learning.

- If pupils struggle, break it down further or reframe the challenge.

Final thought: hands-on, minds-on science

Science should be a subject of curiosity, not compliance. When we shift practicals from tick-box activities to genuine investigations, students become scientists – not just science learners.

By ensuring every practical is intellectually engaging as well as physically interactive, we help pupils develop not just knowledge, but scientific thinking. And that’s the ultimate goal: to create independent, curious learners who don’t just ask, “Are we doing a practical?”, but “Can we investigate this further?”

Related reading and resources:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

KS2

pedagogy

science

sciencepedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

30 January 2025

|

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, outlines the use of “thinking booklets” to embed challenge into the early years setting.

At Alfreton Nursery School, staff believe that children need an intrinsic level of challenge to enhance learning. This challenge is not always based around adding symbols to a maths problem or introducing scientific language to the magnet explorations. An early years environment has countless opportunities for challenge and this challenge can be provided in creative ways.

Thinking booklets: invitations to think and talk

Within the nursery environment, Alfreton has created curriculum zones. These zones lend themselves to curriculum progression, whilst also providing a creative thread of enquiry which runs through all areas. Booklets can be found in each space and these booklets ask abstract questions and offer provocations for debate. Drawing on the pedagogical approach Philosophy for Children (p4c), we use these booklets to ensure classroom spaces are filled with invitations to think and talk.

Literacy booklets

Booklets within the literacy area help children to reflect on the concepts of reading and writing, whilst promoting communication, breadth of vocabulary and the skills to present and justify an opinion.

For example, within the “Big Question: Writing” booklet, staff and children can find the following questions:

- What is writing?

- If nobody could read, would we still need to write?

Alongside these and other questions, there are images of different types of writing. Musical notation, cave drawings, computer text and graffiti to name but a few. Children are empowered to discuss what their understanding of writing actually is and whether others think the same. Staff are careful not to direct conversations or present their own views. Alongside these and other questions, there are images of different types of writing. Musical notation, cave drawings, computer text and graffiti to name but a few. Children are empowered to discuss what their understanding of writing actually is and whether others think the same. Staff are careful not to direct conversations or present their own views.

Maths booklets

Maths booklets are based around all aspects of the subject: shape, size, number. . .

- If a shape doesn’t have a name, is it still a shape?

- What is time?

- If you could be a circle or a triangle, which would you choose and why?

Questions do not need to be based around developing subject knowledge, and the more abstract and creative the question, the more open to all learners the booklets become.

Children explore the questions and share views. On revisiting these questions another day, often opinions will change or become further embellished. Children become aware that listening to different points of view can influence thinking.

Creative questions

Developing the skills of abstract thought and creative thinking is a powerful gift and children enjoy presenting their theories, whilst sometimes struggling to understand that there is no right or wrong answer. For the more analytical thinkers, being asked to consider whether feelings are alive – leading to an exploration of the concept “alive” – can be highly challenging. Many children would prefer to answer, “What is two and one more?”

Alfreton Nursery School’s culture of embracing enquiry, open mindset and respect for all supports children’s levels of tolerance, whilst providing cognitive challenge and opportunities for aspirational discourse. The use of simple strategies to support challenge in the classroom ensures that challenge for all is authentically embedded into our early years practice.

Read more from Alfreton Nursery School:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

early years foundation stage

enquiry

oracy

pedagogy

philosophy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Oliver Barnes,

04 December 2024

|

Ollie Barnes is lead teacher of history and politics at Toot Hill School in Nottingham, one of the first schools to attain NACE Challenge Ambassador status. Here he shares key ingredients in the successful addition of a module on Hong Kong to the school’s history curriculum. You can read more in this article published in the Historical Association’s Teaching History journal.

When the National Security Law came into effect in Hong Kong, it had a profound and unexpected impact 6000 miles away, in Nottinghamshire’s schools. Important historical changes were in process and pupils needed to understand them. As a history department in a school with a growing cohort of Hong Kongers, it became essential to us that students came to appreciate the intimate historical links between Hong Kong and Britain and this history was largely hidden, or at least almost entirely absent, in the history curriculum.

But exploring Hong Kong gave us an opportunity to tell our students a different story, explore complex concepts and challenge them in new ways. Here I will outline the opportunities that Hong Kong can offer as part of a broad and diverse curriculum.

Image source: Unsplash

1. Tell a different story

In our school in Nottinghamshire, the student population is changing. Since 2020, the British National Overseas Visa has allowed hundreds of families the chance to start a new life in the UK. Migration from Hong Kong has rapidly increased. Our school now has a large Cantonese-speaking cohort, approximately 15% of the school population. The challenge this presented us with was how to create a curriculum which is reflective of our students.

Hong Kong offered us a chance to explore a new narrative of the British Empire. In textbooks, Hong Kong barely gets a mention, aside from throwaway statements like ‘Hong Kong prospered under British rule until 1997’. We wanted to challenge our students to look deeper.

We designed a learning cycle which explored the story of Hong Kong, from the Opium Wars in 1839 to the National Security Law in 2020. This challenged our students to consider their preconceptions about Hong Kong, Britain’s impact and migration.

2. Use everyday objects

To bring the story to life, we focused on everyday objects, which are commonly used by our students and could help to tell the story.

First, we considered a cup of tea. We asked why a drink might lead to war? We had already explored the Boston Tea Party, as well as British India, so students already knew part of this story, but a fresh perspective led to rich discussions about war, capitalism, intoxicants and the illegal opium trade.

Our second object was a book, specifically Mao’s Little Red Book. We used it to explore the impact of communism on China, showing how Hong Kong was able to develop separately, with a unique culture and identity.

Lastly, an umbrella. We asked: how might this get you into trouble with the police? Students came up with a range of uses that may get them arrested, before we revealed that possessing one in Hong Kong today could be seen as a criminal act. This allowed us to explore the protest movement post-handover.

At each stage of our enquiry, objects were used to drive the story, ensuring all students felt connected to the people we discussed.

Umbrella Revolution Harcourt Road View 2014 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

3. Keep it complex

In order to challenge our students, we kept it complex. They were asked to draw connections and similarities between Hong Kong and other former British colonies. We also wanted them to encounter capitalism and communism, growth and inequality. Hong Kong gave us a chance to do this in a new and fresh way.

Part of this complexity was to challenge students’ preconceptions of communism, and their assumptions about China. By exploring the Kowloon walled city, which was demolished in 1994, students could discuss the problems caused by inequality in a globalised capitalist city.

Image source: Unsplash

What next?

Our Year 9 students responded overwhelmingly positively. The student survey we conducted showed that they enjoyed learning the story and it helped them understand complex concepts.

Hong Kong offers curricula opportunities beyond the history classroom. In English, students can explore the voices of a silenced population, forced to flee or face extradition. In geography, Hong Kong offers a chance to explore urbanisation, the built environment and global trade.

Additional reading and resources

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

enquiry

history

KS3

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

11 November 2024

|

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, explores the power of metacognition in empowering young people to overcome potential barriers to achievement.

Disadvantage presents itself in different ways and has varying levels of impact on learners. It is important to remember that disadvantage is wider than children who are in receipt of pupil premium or children who have a special educational need. Disadvantage can be based around family circumstances, for example bereavement, divorce, mental health… Disadvantages can be long-term or short-term and the fluidity of disadvantage needs to be acknowledged in order for educators to remain effective and vigilant for all children, including more able learners. If we accept that disadvantage can impact any child at any time, then it is essential that we provide all children with the tools they need to navigate challenge.

More able learners are as vulnerable to the impact of disadvantage as other learners and indeed research would suggest that outcomes for more able learners are more dramatically impacted by disadvantage than outcomes for other children. A cognitive toolbox that is familiar, understood and accessible at all times, can be a highly effective support for learners when there are barriers to progress. By ensuring that all learners are taught metacognition from the beginning of their educational journey and year on year new metacognition skills are integrated, a child is empowered to maintain a trajectory for success.

How can metacognition reduce barriers to learning?

Metacognition supports children to consciously access and manipulate thinking strategies, thus enabling them to solve problems. It can allow them to remain cognitively engaged for longer, becoming emotionally dysregulated less frequently. A common language around metacognition enables learners to share strategies and access a clear point of reference, in times of vulnerability. Some more able learners can find it hard to manage emotions related to underachievement. Metacognition can help children to address both these emotional and cognitive demands.

In order for children to impact their long-term memory and fully embed metacognitive strategies, educators need to teach in many different ways. Metacognition needs to be visually reflected in the learner’s environment, supporting teachers to teach and learners to learn.

How do we do this at Alfreton Nursery School?

At Alfreton Nursery School we ensure that discourse is littered with practical examples of how conscious thinking can result in deeper understanding. Spontaneous conversations are supported by visual aids around the classroom, enabling teachers and learners to plan and reflect on thinking strategies. Children are empowered to integrate the language of metacognition as they explain their learning and strive for greater understanding.

Adults in school use metacognitive terms when talking freely to each other, exposing children to their natural use. Missed opportunities are openly shared within the teaching team, supporting future developments.

Within enrichment groups, metacognition is a transparent process of learning. Children are given metacognitive strategies at the beginning of enhancement opportunities and encouraged to reflect and evaluate at the end. Whether working indoors or outdoors, with manipulatives or abstract concepts and individually or in a group, metacognition is a vehicle through which all learners can access lesson content.

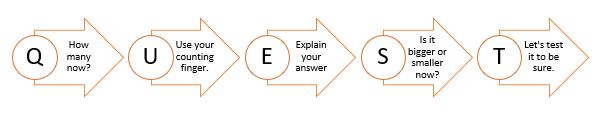

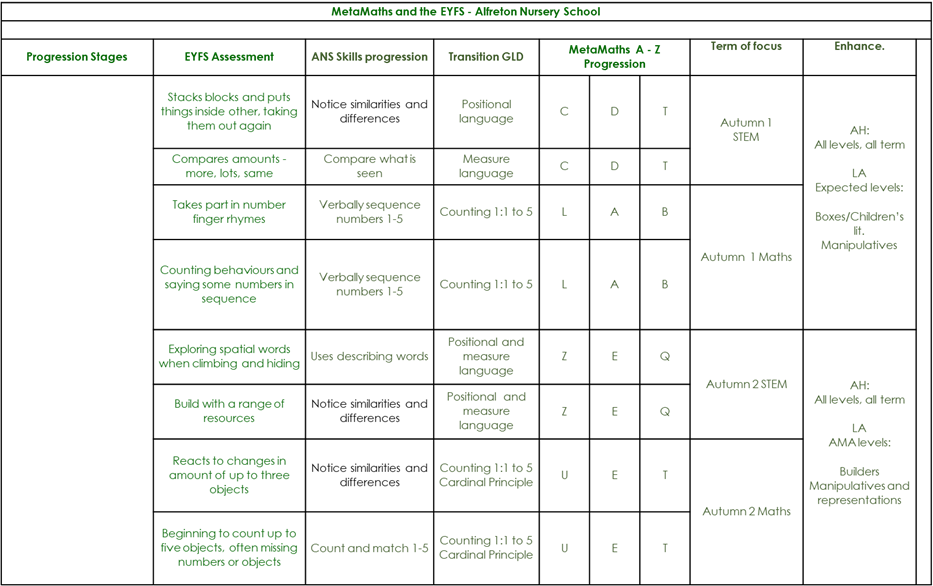

We use the ‘Thinking Moves’ metacognition framework (you can read more about this here). Creative application of this framework supports the combination of metacognition words, to make strings of thinking strategies. For example, a puppet called FRED helps children to Formulate, Respond, Explain and Divide their learning experiences. A QUEST model helps children to follow a process of Questioning, Using, Explaining, Sizing and Testing.

Metacognition supports children of all abilities, ages and backgrounds, to overcome barriers to learning. Disadvantage is thus reduced.

Moving from intent to implementation

Systems and procedures at Alfreton Nursery School serve to scaffold day to day practice and provide a backdrop of expectations and standards. In order to best serve more able children who are experiencing disadvantage, these frameworks need to be explicit in their inclusivity and flexibility. Just as every policy, plan, assessment, etc will address the needs of all learners – including those who are more able – so all these documents explicitly address how metacognition will support all learners. To ensure that visions move beyond ‘intent’ and are fully implemented, systems need to guide provision through a metacognitive lens.

Metacognition is woven into all curriculum documents. A systematic and dynamic monitoring system, which tracks the progress and attainment of all learners, ensures that children have equal focus on cognition and emotion, breaking down barriers with conscious intent.

At Alfreton Nursery School, those children who are more able and experiencing disadvantage receive a carefully constructed meta-curriculum which scaffolds their journey towards success, in whatever context that may manifest itself. Children learn within an environment where teachers can articulate, demonstrate and inculcate the power of metacognition, enabling children to be the best that they can be.

How is your school empowering and supporting young people to break down potential barriers to learning and achievement? Read more about NACE’s research focus for this academic year, and contact us to share your experiences.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

disadvantage

early years foundation stage

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

resilience

underachievement

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Liza Timpson-Hughes,

11 November 2024

|

Liza Timpson-Hughes, Assistant Headteacher at Samuel Ryder Academy, explains how the school and its Trust have embedded oracy education across the curriculum – empowering learners with skills to help them thrive both within and beyond the classroom.

Samuel Ryder Academy is an all-through school and has connected oracy to the development of activating “hard thinking” since 2021. The school is in its third year of working with both NACE and Voice 21, is using the NACE Challenge Framework and was accredited as a Voice 21 Oracy Centre of Excellence in January 2024. Oracy leads and champions are strategically developing talk across all key stages, many of which are now contributing to the implementation of oracy education across the Scholars Educational Trust – a diverse family of 11 schools covering all phases from nursery through to sixth-form.

The focus on developing oracy expertise has strengthened school culture, student experience and staff understanding of challenge in learning. Upon agreeing to focus on oracy, a strong curriculum intent was formed by a group of committed and experienced teachers:

Our oracy curriculum further enables children to speak with confidence, clarity and fluency. This provides them the opportunity to adapt their use of language for a range of different purposes and audiences. It emphasises the value of listening and the ability to interpret and respond appropriately to a range of listening activities. This will be supported by the four key strands of the oracy framework (physical, linguistic, cognitive and social and emotional).

For high-ability students, this focus on oracy matters, because it equips students with the tools they need to succeed academically while also fostering well-rounded individuals who can contribute positively to society. High-ability students often benefit from opportunities to articulate their thoughts and ideas clearly. Engaging in structured discussions and debates allows them to refine their communication skills. We do not only use language to interact, but we also use it to ‘interthink’ (Littleton & Mercer, 2013). Contrary to popular beliefs about ‘lone geniuses’, it is increasingly accepted that effective learning is through collaboration and communication in small groups.

Embedding oracy skills across the curriculum

A great oracy school not only prioritises the development of speaking and listening skills, but also creates a culture where these skills are essential to the learning process. We recognised as a Trust that skills of spoken language and communication do not need to be taught as part of a discrete “oracy lesson” and can be developed effectively as part of well-designed subject curricula. We strongly believed in connecting oracy to our academy development plan and in the value of departments having the autonomy to decide the most effective balance for their own context, ensuring a comprehensive approach to oracy without compartmentalising it into ad hoc basis.

All teachers were asked to plan for oracy episodes in their subject areas at a sequence point they felt worked. There are numerous ways oracy can be integrated into the curriculum. Millard and Menzies (2016) highlight the importance of demonstrating the connection between high-quality talk and academic rigour. Whole-school oracy scaffolds can be used across the curriculum, thus reducing workload for classroom teachers. Additionally, our trained teacher oracy champions offered wider pedagogical support on these oracy scaffolds. They modelled best practice in fortnightly teaching and learning briefings.

Oracy scaffolds to develop classroom talk

Using the Voice 21 Oracy Framework as a springboard, we agreed to focus on scaffolding oracy skills across every subject, building a learning environment in which students could clearly express their thoughts and effectively communicate ideas, whilst understanding what features constituted oracy.

In each subject, teachers prioritised the development of social and emotional skills; central to this was an emphasis on active listening, contributing to a deeper comprehension and retention of information. By actively engaging with peers and teachers, students can enhance their understanding of complex concepts and improve their critical thinking skills.

We first experimented with games and lesson starters using oracy formats and debating ideas from Voice 21. The following approaches have been valuable in every classroom and at every key stage in supporting the development of oracy skills as part of cognitively challenging learning experiences.

- Voice 21 classroom listening ladders: high-ability students can take on leadership roles in group discussions, facilitating peer learning and mentoring others, which not only reinforces their understanding but enhances their social and emotional skills.

- Student age-related oracy frameworks from Voice 21: to encourage high-ability students to articulate their learning processes, reflect on their contributions, and assess their growth.

- Sentence stems and talking roles: high-ability students thrive in environments that challenge their thinking. Oracy practices with sentence stems support argumentation, encourage deep analysis and critical reasoning.

- Voice 21 good discussion guidelines: exposure to diverse perspectives can challenge high-ability students’ thinking and expand intellectual horizons.

- Proof of listening guidelines from Voice 21: listening helps high-ability students build better relationships with their peers and teachers. When students feel heard, they are more likely to engage and participate in the learning process, creating a positive and inclusive classroom atmosphere.

- Student talk tactics and sentence stems from Voice 21 for every discussion and debate: high-ability students thrive in environments that challenge their thinking, and these tactics stimulate intellectual curiosity and critical analysis. These improved whole-class discussions and have greatly impacted group work as the children are more focused, listen carefully to others, build on their ideas, embed learning and address misconceptions. Overall, it has helped students to become confident, eloquent individuals and created a more effective learning environment.

Public speaking practice

Student anxiety around speaking in front of others can deter teachers from incorporating oracy-based activities into lessons. Oracy education has given us a consistent language and a structure to help students as they approach presentational work.

Students were supported to deliver presentations or take part in debates by using bespoke/ age-related versions of the Voice 21 framework. Oracy champions asked students to suggest topics they felt most confident and comfortable with to start their practice. We have ‘Talk Tuesdays’ where all form time and lessons start with a talk-based task.

By establishing clear expectations for classroom talk, students felt more confident to present. These ‘ground rules’ were co-constructed with the students and regularly reviewed. The creation of safe and supportive classrooms was greatly valued by students and necessary before presentational talk. Gradual low-stakes oracy allowed confidence to evolve. Students were then invited to co-present assemblies, address different stakeholders, facilitate student cabinets and student leadership panels, and by sixth form they mastered the skills to deliver TEDx talks.

In geography, for example, students understand that there are different elements to a successfully delivered presentation, whether this was a news report on wildfires filmed on their iPad or a formal presentation to the class on a sustainable city they have designed. Students focused not just on the content (cognitive), but also on their physical and linguistic abilities. Students are delivering much higher-quality work, with much greater confidence, because they understand and consider all the different features. They are also engaging much more with peer feedback, as again we have given them a consistent language to help them evaluate each other’s work.

Teachers discussed the different types of talk that are engaged in group discussions and started to consider ways in which we could encourage more exploratory talk. We wanted to build the students’ skills in employing exploratory talk, and to ‘give permission’ for teachers and students to employ it.

Dialogic learning communities

Increased confidence in exploratory and presentational talk has allowed teachers to consider dialogic learning. Dialogue means being able to articulate ideas seen from someone else’s perspective; it is characterised by chains of (primarily open) questions and answers; it may be sustained over the course of a single lesson or across lessons; and it builds on the idea of ‘exploratory talk’, where learners construct shared knowledge and are willing to change their minds and critique their own ideas (Prof. Neil Mercer, 2000). Our teachers are being encouraged to consider where this fits in their pedagogy, classrooms and curriculum.

Noticeably in maths and RS lessons, the resources provided by Voice 21 have been crucial to create and develop a dialogic culture. We have shared with all students discussion guidelines, talk like a mathematician/philosopher sentence starters, as well as student talking tactics. These resources are displayed in classrooms and have been uploaded digitally onto students’ devices. There is deliberativeness of the dialogue between teachers and students. Seeing rich mathematical or philosophical talk in action surfaced several practices that we believe deepen thinking and strengthen subject content. Linking language to the creativity of mathematical thinking and practices encourages students to use talk as a tool for generating new ways of approaching problems, rather than simply to internalise existing methods and just being compliant passengers.

A stronger voice within and beyond the classroom

Senior leaders play a key role in supporting teachers to develop this oracy knowledge. We provided oracy-specific training for all teaching and support staff. Space was identified for colleagues to share and evaluate the best tools over time. We were particularly interested in understanding how oracy skills promoted greater depth of subject knowledge. The development of oracy skills is most effective when it is integrated into a whole-school approach, endorsed and prioritised by the senior leadership team. But identification of early shifters and adopters was crucial in forming a strong of teacher oracy champions.

For teachers, the shift is noticeable in the modelling of talk they expect from students, scaffolding their responses and interactions and providing timely and specific feedback. It was vital to consider how to approach the teaching of ‘active listening’ in classrooms. We recognised that an oracy-centred approach can be of great value in all subjects but may need adapting to suit the subject area and age of learners.

Since prioritising oracy there is nothing forced or artificial about the classroom conversation; students engage positively with explicit strategies for talk. Students talk about how oracy education has given them increased confidence, a voice for learning and beyond the classroom, and supports their wellbeing. They know this will help them throughout educational transitions and ultimately in the wider world. It is empowering. The impact is evident, not only on high-achieving students but across the entire school culture.

References and further reading

Tags:

cognitive challenge

confidence

language

oracy

pedagogy

questioning

student voice

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

17 April 2023

Updated: 17 April 2023

|

NACE Associate Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Challenge Award-accredited Alfreton Nursery School, explains why and how environmental education has become an integral part of provision in her early years setting.

1. What’s the intent?

The ethics of teaching children of all ages about sustainability is clear. However, teaching such big concepts with such small children needs careful thought. The intention at Alfreton Nursery School is to stimulate an enquiring mind and to nurture children to believe in a solutions-based future.

Exposure to climate change from an adult perspective is dripping into our children’s awareness all the time. At Alfreton Nursery School we believe it is so important to take the current climate and give children a voice and a role within it. The invincibility of the early years mindset has been harnessed, with playful impact.

2. How do I implement environmental education with four-year-olds?

Environment

Just as an effective school environment supports children’s mathematical, creative (etc) development, so our environment at Alfreton is used to educate children on the value of nature. The resources we use are as ethically made and resourced as possible. We use recycled materials and recycled furniture, and lights are on sensors to reduce power consumption.

Like many schools, we have adapted our environment to work with the needs of the planet, and at Alfreton we make our choices explicit for the children. We talk about why the lights don’t stay on all the time, why we have a bicycle parking area in the carpark and why we are sitting on wooden logs, rather than plastic chairs. Our indoor spaces are sprinkled with beautiful large plants, adding to air quality, aesthetics and a sense of nature being a part of us, rather than separate. Incidental conversations about the interdependence of life on our planet feed into daily interactions.

Our biophilic approach to the school environment supports wellbeing and mental health for all, as well as supporting the education of our future generations.

Continuous provision and enhancements

Within continuous provision, resources are carefully selected to enhance understanding of materials and environmental impact. We have not discarded all plastic resources and sent them to landfill. Instead we have integrated them with newer ethical purchasing and take the opportunity to talk and debate with children. Real food is used for baking and food education, not for role play. Taking a balanced approach to the use of food in education feels like the respectful thing to do, as many of our families exist in a climate of poverty.

Larger concepts around deforestation, climate change and pollution are taught in many ways. Our provision for more able learners is one way we expand children’s understanding. In the Aspiration Group children are taught about the world in which they live and supported to understand their responsibilities. We look at ecosystems and explore human impact, whilst finding collaborative solutions to protect animals in their habitats. Through Forest Schools children learn the need to respect the woodlands. Story and reference literature is used to stimulate empathy and enquiry, whilst home-school partnerships further develop the connections we share with community projects to support nature.

We have an outdoor STEM Hive dedicated to environmental education. Within this space we have role play, maths, engineering, small world, science, music… but the thread which runs through this area is impact on the planet. When engaged with train play, we talk about pollution and shared transport solutions. When playing in the outdoor house we discuss where food comes from and carbon footprints. In the Philosophy for Children area we debate concepts like ‘fairness’ – for me, you, others and the planet. And on boards erected in the Hive there are images of how humans have taken the lead from nature. For example, in the engineering area there are images of manmade bridges and dams, along with images of beavers building and ants linking their bodies to bridge rivers.

3. Where will I see the impact?

Our environmental work in school has supported the progression of children across the curriculum, supporting achievements towards the following goals:

Personal, Social and Emotional Development:

- Show resilience and perseverance in the face of challenge

- Express their feelings and consider the feelings of others

Understanding the World:

- Begin to understand the need to respect and care for the natural environment and all living things

- Explore the natural world around them

- Recognise some environments that are different from the one in which they live

(Development Matters, 2021, DfE)

More widely, children are thinking beyond their everyday lived experience and connecting their lives to others globally. Our work is based on high aspirations and a passionate belief in the limitless capacity of young children. Drawing on the synthesis of emotion and cognition ensures learning is lifelong. The critical development of their relational understanding of self to the natural world has seen children’s mental health improve and enabled them to see themselves as powerful contributors, with collective responsibilities, for the world in which they live and grow.

Read more:

Plus:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

early years foundation stage

pedagogy

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Jonathan Doherty,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

NACE Associate Dr Jonathan Doherty outlines the focus of this year’s NACE R&D Hub on “oracy for high achievement” – exploring the impetus for this, challenges for schools, and approaches being trialled.

This year one of the NACE Research & Development Hubs is examining the theme of ‘oracy for high achievement’. The Hub is exploring the importance of rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse in the context of shared classroom practice. School leaders and teachers participating in the Hub are seeking to improve the value and effectiveness of speaking and listening. They are developing a body of knowledge about provision and pedagogy for more able learners, sharing ideas and practice and contributing to wider research evidence on oracy through their classroom-based enquiries.

Why focus on oracy?

Oracy is one of the most used and most important skills in schools. To be able to speak eloquently and with confidence, to articulate thinking and express an opinion are all essential for success both at school and beyond. Communication is a vital skill for the 21st century from the early years, through formal education, to employment. It embraces skills for relationship building, resolving conflict, thinking and learning, and social interaction. Oral language is the medium through which children communicate formally and informally in classroom contexts and the cornerstone of thinking and learning. The NACE publication Making Space for Able Learners found that “central to most classroom practice is the quality of communication and the use of talk and language to develop thinking, knowledge and understanding” (NACE, 2020, p.38).

Oracy is very much at the heart of classroom practice: modern classroom environments resound to the sound of students talking: as a whole class, in group discussions and in partner conversations. Teachers explaining, demonstrating, instructing and coaching all involve the skills of oracy. Planned purposeful classroom talk supports learning in and across all subject areas, encouraging students to:

- Analyse and solve problems

- Receive, act and build upon answers

- Think critically

- Speculate and imagine

- Explore and evaluate ideas

Dialogic teaching’ is highly influential in oracy-rich classrooms (Alexander, 2004). It uses the power of classroom talk to challenge and stretch students. Through dialogue, teachers can gauge students’ perspectives, engage with their ideas and help them overcome misunderstandings. Exploratory talk is a powerful context for classroom talk, providing students with opportunities to share opinions and engage with peers (Mercer & Dawes, 2008). It is not just conversational talk, but talk for learning. Given the importance and prevalence of classroom talk, it would be easy to assume that oracy receives high status in the curriculum, but its promotion is not without obstacles to overcome.

Challenges for schools in developing oracy skills

Covid-19 has impacted upon students’ oracy. A report from the children’s communication charity I CAN estimated that more than 1.5 million UK young people risk being left behind in their language development as a result of lost learning in the Covid-19 period (read more here). The Charity reported that the majority of teachers were worried about young people being able to catch up with their speaking and understanding as a result of the pandemic (I CAN, 2021).

With origins going back to the 1960s, the term oracy was introduced as a response to the high priority placed on literacy in the curriculum of the time. Rien ne change, with the current emphasis remaining exactly so. Literacy skills, i.e. reading and writing, continue to dominate the curriculum. Oracy extends vocabulary and directly helps with learning to read. The educationalist James Nimmo Britton famously said that “good literacy floats on a sea of talk” and recognised that oracy is the foundation for literacy.

Teachers do place value on oracy. In a 2016 survey by Millard and Menzies of 900 teachers across the sector, over 50% said they model the sorts of spoken language they expect of their students, they do set expectations high, and they initiate pair or group activities in many lessons. They also highlighted the social and emotional benefits of oracy and suggested it has untapped potential to support pupils’ employability – but reported that provision is often patchy and that CPD was sparse or even non-existent.

Another challenge is that oracy is mentioned infrequently in inspection reports. An analysis of reports of over 3,000 schools on the Ofsted database, undertaken by the Centre for Education and Youth in 2021, found that when taken in the context of all school inspections taking place each year, oracy featured in only 8% of reports.

The issue of how oracy is assessed is a further challenge. Assessment profoundly influences student learning. Changes to assessment requirements now provide schools with new freedoms to ensure their assessment systems support pupils to achieve challenging outcomes. Despite useful frameworks to assess oracy such as the toolkit from the organisation Voice 21, there is no accepted system for the assessment of oracy.

What are NACE R&D Hub participants doing to develop oracy in their schools?

The challenges outlined above make the work of participants in the Hub of real importance. With a focus on ‘oracy for high achievement’, the Hub is supporting teachers and leaders to delve deeper into oracy practices in their classrooms. The Hub supports small-scale projects through which they can evidence the impact of change and evaluate their practice. Activities are trialled over a short period of time so that their true impact can be observed in school and even replicated in other schools.

The participants are now engaged in a variety of enquiry-based projects in their classrooms and schools. These include:

- Use of the Harkness Discussion method to enable more able students to exhibit greater depth of understanding, complexity of response and analytical skills within cognitively challenging learning;

- Explicit teaching of oracy skills to improve independent discussion in science and history lessons;

- Introduction of hot-seating to improve students’ ability to ask valuable questions;

- Choice in oral tasks to improve the quality of students’ analytical skills;

- Oracy structures in collaborative learning to challenge more able students’ deeper learning and analysis;

- Better reasoning using oracy skills in small group discussion activities;

- Interventions in drama to improve the quality of classroom discussion.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective oracy practices, including new initiatives and well-established practices. You may feel that some of the examples above are similar to practices in your own school, or you may have well-developed models of oracy teaching and learning that would be of interest to others. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- How can we implement effective oracy strategies without dramatically increasing teacher workload?

- How can we best develop oracy for the most able in mixed ability classrooms?

- What approaches are most effective in promoting oracy in group work so that it is productive and benefits all learners?

- How can we implicitly teach pupils to justify and expand their ideas and make clear opportunities to develop their understanding through talk and deepen their understanding?

- How do we evidence challenge for oracy within lessons?

Teachers should develop students’ spoken language, reading, writing and vocabulary as integral aspects of the teaching of every subject. Every teacher is a teacher of oracy. The report of the All-Party Parliamentary Group inquiry into oracy in schools concluded that there was an indisputable case for oracy as an integral aspect of education. This adds to a growing and now considerable body of evidence to celebrate the place that oracy has in our schools and in our society. Oracy is in a unique place to support the learning and development of more able pupils in schools and the time to give oracy its due is now.

References

- Alexander, R. J. (2004) Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. York, UK: Dialogos.

- Britton, J. (1970) Language and learning. London: Allen Lane. [2nd ed., 1992, Portsmouth NH: Boynton/Cook, Heinemann].

- I CAN (2021) Speaking Up for the Covid Generation. London: I CAN Charity.

- Lowe, H. & McCarthy, A. (2020) Making Space for Able Learners. Didcot, Oxford: NACE.

- Mercer, N. &. Dawes., L. (2008) The Value of Exploratory Talk. In Exploring Talk in School, edited by N. Mercer and S. Hodgkinson, pp. 55–71. London: Sage.

- Millard, W. & Menzies, L. (2016) The State of Speaking in Our Schools. London: Voice 21/LKMco.

- Millard, W., Menzies, L. & Stewart, G. (2021) Oracy after the pandemic: what Ofsted, teachers and young people think about oracy. Centre for Education & Youth/University of Oxford.

Read more:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

collaboration

confidence

CPD

critical thinking

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

policy

questioning

research

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Gianluca Raso,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

Gianluca Raso, Senior Middle Leader for MFL at NACE Challenge Award-accredited Maiden Erlegh School, explores the real meaning of “adaptive teaching” and what this means in practice.

When I first came across the term “adaptive teaching”, I thought: “Is that not what we already do? Surely, the label might be new, but it is still differentiation.” Monitoring progress, supporting underperforming students and providing the right challenge for more able learners: these are staples in our everyday practice to allow students to actively engage with and enjoy our subjects.

I was wrong. Adaptive teaching is not merely differentiation by another name. In adaptive teaching, differentiation does not occur by providing different handouts or the now outdated “all, most, some” objectives, which intrinsically create a glass ceiling in students’ achievement. Instead, it happens because of the high-quality teaching we put in for all our students.

Adaptive teaching is a focus of the Early Career Framework (DfE, 2019), the Teachers’ Standards, and Ofsted inspections. It involves setting the same ambitious goals for all students but providing different levels of support. This should be targeted depending on the students’ starting points, and if and when students are struggling.

But of course it is not as simple as saying, “this is what adaptive teaching means: now use it”.

So how, in practice, do we move from differentiation to adaptive teaching?

A sensible way to look at it is to consider adaptive teaching as an evolution of differentiation. It is high-quality teaching based on:

- Maintaining high standards, so that all learners have the opportunity to meet expectations.

Supporting all students to work towards the same goal but breaking the learning down – forget about differentiated or graded learning objectives.

- Balancing the input of new content so that learners master important concepts.

Giving the right amount of time to our students – mastery over coverage.

- Knowing your learners and providing targeted support.

Making use of well-designed resources and planning to connect new content with pupils' prior knowledge or providing additional pre-teaching if learners lack critical knowledge.

- Using Assessment for Learning in the classroom – in essence check, reflect and respond.

Creating assessment fit for purpose – moving away from solely end of unit assessments.

- Making effective use of teaching assistants.

Delivering high quality one-to-one and small group support using structured interventions.

In conclusion, adaptive teaching happens before the lesson, during the lesson and after the lesson.

Aim for the top, using scaffolding for those who need it. Consider: what is your endgame and how do you get there? Does everyone understand? How do you know that? Can everyone explain their understanding? What mechanisms have you put in place to check student understanding ? Encourage classroom discussions (pose, pause, pounce, bounce), use a progress checklist, question the students (hinge questions, retrieval practice), adapt your resources (remove words, simplify the text, include errors, add retrieval elements).

Adaptive teaching is a valuable approach, but we must seek to embed it within existing best practice. Consider what strikes you as the most captivating aspect of your curriculum in which you can enthusiastically and wisely lead the way .

Ask yourself:

- Could all children access this?

- Will all children be challenged by this?

… then go from there…

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

differentiation

feedback

pedagogy

professional development

progression

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

20 February 2023

Updated: 20 February 2023

|

NACE Associate Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Challenge Award-accredited Alfreton Nursery School, shares five key approaches to embed metacognition in the early years.

At Alfreton Nursery School metacognition has been systematically embedded across the whole curriculum for the last three years. Through the use of an approach constructed by Roger Sutcliffe (DialogueWorks) called Thinking Moves, we’ve successfully implemented an innovative approach to learning.

When we talk about the progression of mathematical understanding we have a shared language. We all understand what it means to engage in addition and subtraction. Phonics, science . . . all areas of learning have a common linguistic foundation.

However, when it comes to the skills of thinking and learning, there is no common language and the concepts are shrouded in misconception. Do children learn visually, kinaesthetically . . . ? Are there different levels to learning? Based on the belief that we are all thinking and learning all of the time, Thinking Moves has been implemented at Alfreton Nursery School. Thinking Moves provides the language to explain the process of thinking and has thus provided a common framework on which to master learning.

1. Develop and model a shared vocabulary

A shared vocabulary, used by all staff and children, has provided the adults with a tool to explain teaching, and the children with a tool to aid learning. Crucially, the commonality in language means that learning is transparent. For example, when children explain what comes next in a story, they are using the A in the A-Z: thinking Ahead. During the story recall children are using B: thinking Back. The A-Z of Thinking Moves supports children to consciously choose and communicate the thinking strategies they intend to use, are using, or have used to achieve success.

Teaching staff build on the more commonly used Thinking Moves words, whilst subtly introducing less familiar terms. The use of synonyms within conversation, to accompany the language of Thinking Moves, supports both adults and children to use the words in context.

“I’m going to think ahead, cos I need to choose the bricks I need to build my rocket.”

2. Embed metacognitive concepts in the learning environment

The learning environment critically supports the children’s use of metacognition. With each word comes a symbol. These symbols are used to visually illustrate Thinking Moves. Children use these symbols to explain what type of thinking they are engaged in and what they need to do next.

The integration of the symbols into the classroom environment has ensured that there is conscious intent to implement metacognition within all areas of the curriculum. Teachers use the symbols as prompts. Children use the symbols to help them articulate their thinking and as an aid to knowing what strategies will help them further.

Through immersing children in the visual world of metacognition, all children – regardless of age and stage of development – are supported in their learning.

3. Break it down into manageable chunks

The A-Z includes some words which slide easily into conversation. Other words are less easily integrated into everyday speech. In order to ensure that a variation of language is incorporated throughout the curriculum, specific areas of the curriculum have dedicated Thinking Moves words. For example, Expressive Art and Design have embraced the metacognitive moves of Vary, Zoom and Picture. This ‘step by step’ strategy gives teaching staff the confidence to learn and use the A-Z in small chunks.

Over time, as confidence grows, the use of metacognitive language becomes a natural part of daily discourse. Whether in the staffroom over lunch, planning the timetable or sharing a jigsaw, metacognition has become a part of daily life.

4. Use to support targeted teaching across the curriculum

Metacognition is embedded throughout continuous provision and is accessed by all children through personalised interactions. Enhancements are offered across the curriculum and metacognition forms a vehicle on which targeted teaching is delivered. For example, by combining thinking moves together, we have created thinking grooves. By using certain moves together, the flow of thinking is explicit.

Within our maths enhancements we use the maths QUEST approach. A session begins with a Question, e.g. “How many will we have if we add one more to this group?” Children Use their mathematical understanding and Explain what they will need to do to solve the problem. The answer is Sized, “Are there more or less now?”, and then this is Tested to establish the consistency of the answer. Maths QUESTs now underpin our mathematical enhancements, allowing children to consciously use maths and metacognition simultaneously.

5. Embed within progression planning

When looking at the curriculum and skill progression across the school, it has been helpful to consider which Thinking Moves explicitly support advancement. For children to progress in their acquisition of new concepts, they need to know clearly how to access their learning. Within our planning and assessment systems, areas of metacognitive focus have been identified.

For example, within literacy we have raised our focus on the Thinking Move Infer. For children to gather information from a story is a key skill for future progression. Within science we emphasise the need to Test and within music we support children to Respond. Progression planning now has a clear focus on cognitive challenge, as well as subject knowledge.

Embedding metacognition in the early years supports children to master their own cognition and gives them a voice for life.

Further reading:

Plus:

Tags:

critical thinking

early years foundation stage

metacognition

pedagogy

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|