Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Raglan CiW VC Primary School,

11 November 2024

|

Marc Bowen, Deputy Headteacher and Year 5 Class Teacher at NACE member school Raglan CiW VC Primary School, shares how he has developed his classroom environment to remove potential barriers to learning for neurodivergent learners.

It has long been my experience that a proportion of the more able learners that I have had the pleasure of teaching, have also experienced the additional challenge of neurodivergent needs, whether they be diagnosed or not.

With this in mind, over the past few years I have been proactively exploring means of making my primary classroom more neurodivergent-friendly for the benefit of all learners, including those more able children that might find concentration, focus or communicating their understanding to be a challenge.

Here are a few ways in which I have tried to ensure that our learning environment enables effective learning conditions for all the children in my class, as well as benefitting those who are particularly able.

Flexible seating

Over a number of years, I have been able to increasingly vary the workspaces available in our classroom. These include:

1. The Cwtch (a well know Welsh term for a ‘hug’), which comprises a low-slung canopy under which children can sit on an array of cushions, as well as choosing their favoured colour of diffused lighting through the use of wall-mounted push-lights. This not only helps to create a more enclosed space for those who need it, but it also helps to suppress ambient noise and echoes, for those that might have sensory needs. Some of my more able learners who are challenged by distraction routinely use this space to help channel their focus.

2. The Standing Station, which does what is says on the tin! We have a high-level table which the children can easily and comfortably stand at to work. This has proven to be one of the most popular spaces and I have noted that some of my more able learners will make use of this space during the early stages of an independent task, when they might need to order or distil their thinking. The ability to move from foot to foot and move more freely appears to aid this level of thinking.

3. The Carpet Surfer Seats are ‘s’ shaped plastic seats, designed to be used when working on a carpet space. They compromise a seat, which when sat upon offers a raised work surface in front of the child. These really helped to increase the flexible seating options in the class, as the children can now easily make comfortable use of any carpet/floor space rather than struggling to find a comfortable working position. I have noted that my more able learners appreciate these when they want to work in collaboration with others but, due to their neurodivergent needs, might find the free-flow of collaborative working a challenge. The Carpet Surfer Seat gives them a defined workspace of their own, allows them to move to any more comfortable position when working collaboratively, and also provides needed stability for those more able learners I have taught who are challenged by coordination-based neurodivergence.

4. Beanbag Corner offers a solo working space on a structural (high-backed) beanbag which is close to my teacher’s base within the class. I find that this is regularly used by those more able learners who do find concentration and focus a challenge, whilst also requiring the reassuring proximity of an adult for a sense of comfort and/or to allow for informal check-ins with the teacher to tackle low-level anxiety issues.

Lighting

As with most school settings, the standard lighting fitted throughout the school is overhead, downward channel cold-white LED lighting arrays. I have noticed personally that when this is combined with the stark white table surfaces, the effect can be quite dazzling when working at these tables. The children themselves had commented on how ‘bright’ the room was, with one more able learner commenting that he ‘felt better’ during a dressing-up day when he was wearing sunglasses. This got me thinking of ways to mitigate this and, as a result, I have explored a number of different light options:

1. Dimming the overhead lights: I discovered, by accident, that if the classroom light switches are held in they act as dimmer controls for the overhead lighting. (Might be worth a try in your classroom!) It has now become standard practice for me to dim all the lighting by about 50% at the start of each day, which immediately creates a less harsh lighting environment.

2. Colour-changing rechargeable lights have also been a huge benefit. I have placed a number of these within and around my flexible working spaces, in the form of wall-mounted and table-top tap/push lights which the children can use to choose their favoured lighting conditions when working in a space. I have noticed that my more able learners typically opt for softer tones of yellow, orange or purple light.

3. Uplighters, purchased with the benefit of some funding from a local business, have had a huge impact. They allow us to create brighter working areas for those who respond well to those conditions, whilst providing diffused light, rather than overhead lights that create shadows over workspaces. In addition, these have helped to define our flexible spaces, such as the uplighter which includes a secondary directional light that sits above the Beanbag Corner.

4. Natural light is essential! We are a newbuild school but the natural lighting options are limited. As such, I make sure that all our blinds and curtains are pulled back to the extreme to ensure that as much natural light as possible can flood into the room.

Fidgets

I’m sure that some teachers will find the use of hand-held fidget objects a nightmarish challenge in a busy classroom, and if used improperly I would agree. However, the structured use of fidgets in our classroom has brought some major benefits for my more able learners who might struggle to maintain focus or settle for an extended period. We manage these by having a jar of different objects which are freely available to all children (rather than being targeted at a limited number of specific learners) and we have an open, frank conversation about how to use these at the start of the term.

Our conditions for their use are:

- If you choose to use a fidget, your focus must remain on the learning activity or discussion.

- If a fidget becomes a distraction, it is replaced in the jar immediately.

In addition, I have also experimented with different types of fidget, eliminating anything that is overly complex, noisy or too similar to a toy. Currently, the most successful types (which I now do not ‘notice’ as a distraction at any point) are rubber hand stretchers (loops that go over each digit and provide stretchy resistance), plastic wing-nuts and screw threads, and silent button/wheel fidgets (they resemble a palm-sized game controller, offering a pleasing sensation in the hand too).

Additional reading

There are some excellent online sources of information, including education-focused social media posts, where teachers share their own flexible seating/classroom environment approaches. In addition, some interesting reading that I have accessed has been:

- Fedewa, A. L., Davis, M. A., & Ahn, S. (2015). The Effects of Physical Activity and Physical Classroom Environment on Children’s On-Task Behavior: A Meta-Analysis. Educational Psychology Review.

- Kroeger, S., & Schultz, T. (2020). Sensory Spaces: Creating Inclusive Classrooms for Students with Sensory Needs. Inclusive Education Journal.

- Rands, M. L., & Gansemer-Topf, A. (2017). The Role of Classroom Environment in Student Engagement. Journal of Education Research.

How is your school helping to break down barriers to learning?

This year NACE’s research programme is exploring the ways in which schools can help to remove potential barriers to success for more able learners. Find out more and get involved.

Tags:

disadvantage

dual and multiple exceptionality

KS1

KS2

underachievement

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Liza Timpson-Hughes,

11 November 2024

|

Liza Timpson-Hughes, Assistant Headteacher at Samuel Ryder Academy, explains how the school and its Trust have embedded oracy education across the curriculum – empowering learners with skills to help them thrive both within and beyond the classroom.

Samuel Ryder Academy is an all-through school and has connected oracy to the development of activating “hard thinking” since 2021. The school is in its third year of working with both NACE and Voice 21, is using the NACE Challenge Framework and was accredited as a Voice 21 Oracy Centre of Excellence in January 2024. Oracy leads and champions are strategically developing talk across all key stages, many of which are now contributing to the implementation of oracy education across the Scholars Educational Trust – a diverse family of 11 schools covering all phases from nursery through to sixth-form.

The focus on developing oracy expertise has strengthened school culture, student experience and staff understanding of challenge in learning. Upon agreeing to focus on oracy, a strong curriculum intent was formed by a group of committed and experienced teachers:

Our oracy curriculum further enables children to speak with confidence, clarity and fluency. This provides them the opportunity to adapt their use of language for a range of different purposes and audiences. It emphasises the value of listening and the ability to interpret and respond appropriately to a range of listening activities. This will be supported by the four key strands of the oracy framework (physical, linguistic, cognitive and social and emotional).

For high-ability students, this focus on oracy matters, because it equips students with the tools they need to succeed academically while also fostering well-rounded individuals who can contribute positively to society. High-ability students often benefit from opportunities to articulate their thoughts and ideas clearly. Engaging in structured discussions and debates allows them to refine their communication skills. We do not only use language to interact, but we also use it to ‘interthink’ (Littleton & Mercer, 2013). Contrary to popular beliefs about ‘lone geniuses’, it is increasingly accepted that effective learning is through collaboration and communication in small groups.

Embedding oracy skills across the curriculum

A great oracy school not only prioritises the development of speaking and listening skills, but also creates a culture where these skills are essential to the learning process. We recognised as a Trust that skills of spoken language and communication do not need to be taught as part of a discrete “oracy lesson” and can be developed effectively as part of well-designed subject curricula. We strongly believed in connecting oracy to our academy development plan and in the value of departments having the autonomy to decide the most effective balance for their own context, ensuring a comprehensive approach to oracy without compartmentalising it into ad hoc basis.

All teachers were asked to plan for oracy episodes in their subject areas at a sequence point they felt worked. There are numerous ways oracy can be integrated into the curriculum. Millard and Menzies (2016) highlight the importance of demonstrating the connection between high-quality talk and academic rigour. Whole-school oracy scaffolds can be used across the curriculum, thus reducing workload for classroom teachers. Additionally, our trained teacher oracy champions offered wider pedagogical support on these oracy scaffolds. They modelled best practice in fortnightly teaching and learning briefings.

Oracy scaffolds to develop classroom talk

Using the Voice 21 Oracy Framework as a springboard, we agreed to focus on scaffolding oracy skills across every subject, building a learning environment in which students could clearly express their thoughts and effectively communicate ideas, whilst understanding what features constituted oracy.

In each subject, teachers prioritised the development of social and emotional skills; central to this was an emphasis on active listening, contributing to a deeper comprehension and retention of information. By actively engaging with peers and teachers, students can enhance their understanding of complex concepts and improve their critical thinking skills.

We first experimented with games and lesson starters using oracy formats and debating ideas from Voice 21. The following approaches have been valuable in every classroom and at every key stage in supporting the development of oracy skills as part of cognitively challenging learning experiences.

- Voice 21 classroom listening ladders: high-ability students can take on leadership roles in group discussions, facilitating peer learning and mentoring others, which not only reinforces their understanding but enhances their social and emotional skills.

- Student age-related oracy frameworks from Voice 21: to encourage high-ability students to articulate their learning processes, reflect on their contributions, and assess their growth.

- Sentence stems and talking roles: high-ability students thrive in environments that challenge their thinking. Oracy practices with sentence stems support argumentation, encourage deep analysis and critical reasoning.

- Voice 21 good discussion guidelines: exposure to diverse perspectives can challenge high-ability students’ thinking and expand intellectual horizons.

- Proof of listening guidelines from Voice 21: listening helps high-ability students build better relationships with their peers and teachers. When students feel heard, they are more likely to engage and participate in the learning process, creating a positive and inclusive classroom atmosphere.

- Student talk tactics and sentence stems from Voice 21 for every discussion and debate: high-ability students thrive in environments that challenge their thinking, and these tactics stimulate intellectual curiosity and critical analysis. These improved whole-class discussions and have greatly impacted group work as the children are more focused, listen carefully to others, build on their ideas, embed learning and address misconceptions. Overall, it has helped students to become confident, eloquent individuals and created a more effective learning environment.

Public speaking practice

Student anxiety around speaking in front of others can deter teachers from incorporating oracy-based activities into lessons. Oracy education has given us a consistent language and a structure to help students as they approach presentational work.

Students were supported to deliver presentations or take part in debates by using bespoke/ age-related versions of the Voice 21 framework. Oracy champions asked students to suggest topics they felt most confident and comfortable with to start their practice. We have ‘Talk Tuesdays’ where all form time and lessons start with a talk-based task.

By establishing clear expectations for classroom talk, students felt more confident to present. These ‘ground rules’ were co-constructed with the students and regularly reviewed. The creation of safe and supportive classrooms was greatly valued by students and necessary before presentational talk. Gradual low-stakes oracy allowed confidence to evolve. Students were then invited to co-present assemblies, address different stakeholders, facilitate student cabinets and student leadership panels, and by sixth form they mastered the skills to deliver TEDx talks.

In geography, for example, students understand that there are different elements to a successfully delivered presentation, whether this was a news report on wildfires filmed on their iPad or a formal presentation to the class on a sustainable city they have designed. Students focused not just on the content (cognitive), but also on their physical and linguistic abilities. Students are delivering much higher-quality work, with much greater confidence, because they understand and consider all the different features. They are also engaging much more with peer feedback, as again we have given them a consistent language to help them evaluate each other’s work.

Teachers discussed the different types of talk that are engaged in group discussions and started to consider ways in which we could encourage more exploratory talk. We wanted to build the students’ skills in employing exploratory talk, and to ‘give permission’ for teachers and students to employ it.

Dialogic learning communities

Increased confidence in exploratory and presentational talk has allowed teachers to consider dialogic learning. Dialogue means being able to articulate ideas seen from someone else’s perspective; it is characterised by chains of (primarily open) questions and answers; it may be sustained over the course of a single lesson or across lessons; and it builds on the idea of ‘exploratory talk’, where learners construct shared knowledge and are willing to change their minds and critique their own ideas (Prof. Neil Mercer, 2000). Our teachers are being encouraged to consider where this fits in their pedagogy, classrooms and curriculum.

Noticeably in maths and RS lessons, the resources provided by Voice 21 have been crucial to create and develop a dialogic culture. We have shared with all students discussion guidelines, talk like a mathematician/philosopher sentence starters, as well as student talking tactics. These resources are displayed in classrooms and have been uploaded digitally onto students’ devices. There is deliberativeness of the dialogue between teachers and students. Seeing rich mathematical or philosophical talk in action surfaced several practices that we believe deepen thinking and strengthen subject content. Linking language to the creativity of mathematical thinking and practices encourages students to use talk as a tool for generating new ways of approaching problems, rather than simply to internalise existing methods and just being compliant passengers.

A stronger voice within and beyond the classroom

Senior leaders play a key role in supporting teachers to develop this oracy knowledge. We provided oracy-specific training for all teaching and support staff. Space was identified for colleagues to share and evaluate the best tools over time. We were particularly interested in understanding how oracy skills promoted greater depth of subject knowledge. The development of oracy skills is most effective when it is integrated into a whole-school approach, endorsed and prioritised by the senior leadership team. But identification of early shifters and adopters was crucial in forming a strong of teacher oracy champions.

For teachers, the shift is noticeable in the modelling of talk they expect from students, scaffolding their responses and interactions and providing timely and specific feedback. It was vital to consider how to approach the teaching of ‘active listening’ in classrooms. We recognised that an oracy-centred approach can be of great value in all subjects but may need adapting to suit the subject area and age of learners.

Since prioritising oracy there is nothing forced or artificial about the classroom conversation; students engage positively with explicit strategies for talk. Students talk about how oracy education has given them increased confidence, a voice for learning and beyond the classroom, and supports their wellbeing. They know this will help them throughout educational transitions and ultimately in the wider world. It is empowering. The impact is evident, not only on high-achieving students but across the entire school culture.

References and further reading

Tags:

cognitive challenge

confidence

language

oracy

pedagogy

questioning

student voice

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Karen Scott-Woodhouse,

08 May 2024

|

Curriculum for Wales places learner progression at its core, emphasising personalised learning experiences and continuous assessment. In this blog, we’ll explore the key changes, principles, and practical steps for designing an effective assessment and progression strategy.

1. Understanding the Shift

Curriculum for Wales redefines the purpose of assessment. Rather than focusing solely on outcomes, it aims to:

Support individual learners on an ongoing basis.

Capture and reflect on individual learner progress over time.

Understand group progress to inform teaching practices.

2. Key Changes in Assessment

Phases and key stages are replaced with a single continuum of learning. This shift allows educators to view learning as a seamless journey rather than discrete stages. Gone are the days of assigning levels or outcomes based on a single assessment point. Instead, assessment is embedded within teaching and learning, focusing on ongoing progress. Learners are assessed upon entry to a school or setting at any point along the continuum. This personalised approach ensures tailored support and challenge. The new strategy separates teacher assessment from accountability measures. This encourages educators to prioritise formative assessment that informs teaching and learning.

Implementing the assessment and progression strategy in Wales can comes with challenges. Let’s explore these hurdles:

Mindset Shift- educators, parents, and learners need to embrace a new mindset, moving away from traditional assessment practices and understanding the value of ongoing, personalised assessment. Teachers require professional development to effectively implement the strategy. They need training on formative assessment techniques, data interpretation, and adapting to the continuum of learning.

Assessment literacy: Designing custom assessment arrangements demands time, effort, and resources. Schools and settings must allocate resources for planning, implementation, and continuous improvement. Building assessment literacy among educators is essential. They need to understand the purpose, methods, and impact of assessment beyond traditional judgements of outcomes and levels. Striking the right balance between formative (ongoing) and summative (end-of-term) assessments can be tricky since both are necessary for a holistic view of learner progress. Continuous assessment can lead to assessment fatigue for both learners and educators. Managing workload and stress is crucial.

Communication: Transparent communication with parents and carers is crucial. Explaining the shift in assessment practices and addressing concerns can be complex, particularly when ensuring that assessment practices are inclusive and equitable for all learners, regardless of their backgrounds or abilities.

Changing Accountability Measures: Separating assessment from accountability measures requires policy changes and alignment across educational bodies.

3. Practical Steps for Schools and Settings

Each school or setting should create assessment arrangements aligned with its unique curriculum. Flexibility is key.

Transparent communication about assessment practices ensures that parents and carers understand their child’s progress.

Professional dialogue and collaboration with colleagues is essential to build a common understanding of progression.

4. Resources and Further Reading

Detailed guidance for schools and settings

Curriculum for Wales Assessment Poster Pack: Useful visual aids for planning assessment

By designing thoughtful assessment practices, we contribute to a more inclusive and progressive education system in Wales. Remember, assessment isn’t just about measuring; it’s about empowering learners to thrive! 🌟

Agenda

|

|

|

|

|

Context for change in C4W Assessment and Progression

|

|

|

Developing a whole school rationale for ‘Why’ we assess

|

|

|

|

|

|

Developing a whole school overview of ‘How’ Assessment happens

|

|

|

|

|

|

Developing an assessment & progression overview –‘What’ we assess.

|

|

|

Evaluating the value and purpose of current formative and summative assessments

|

|

|

Feedback and key considerations

|

|

|

Understanding Principles of Progression

|

|

|

|

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

05 October 2023

|

P4C has been a pedagogical approach which has been embedded at Alfreton Nursery School for over 5 years. The approach has gradually morphed from being a daily intervention for targeted children, into a whole school, cross curricular approach to teaching and learning.

1. 4Cs

The 4Cs which underpin the P4C philosophy: Caring, Collaborative, Critical and Creative, represent types of thinking to be encouraged within a culture of enquiry. At Alfreton these four approaches to thinking have been adopted as keys to learning and teaching across the curriculum. Children are reminded, for example, of the need to think in a collaborative way when building with blocks, to show caring thinking when in the home corner, apply critical thinking when solving a maths problem and apply their creative thinking when discussing a story. Teachers explicitly model these four Cs and highlight whenever they witness a child using them and they will mirror the use of these thinking approaches, clearly identifying strategies they too are using.

Within story groups the 4Cs are applied with a differentiated approach. In our first story group the focus remains clearly on Caring thinking. As children’s understanding grows, they are then supported to explore the concept of collaborative thinking. More able learners are taught to independently apply all four thinking approaches within these sessions.

2. Enquiry based curriculum

The implementation of P4C across the curriculum has meant that children are taught about open mindsets. Children are taught to wonder, question, debate and share in a climate of respect and acceptance. Opinions rather than facts underpin the way children interact with their learning and rather than being passive receptors of knowledge, children are taught to actively engage with their learning. P4C training encourages teacher reflection and the conscious implementation of role within a lesson. At Alfreton Nursery School teaching staff consider within their planning whether they intend to guide learners from a position of open ended potential or instead to teach with a clearly intended outcome. We believe there is space for both within daily interactions but in order to ensure the balance between adult and child voice, teacher role needs to be clear.

Children are taught the importance of empathy for others perspectives and various stimulus are used to provoke challenge. For more able learners, question quadrants help children understand different types of questions and raise awareness that some questions are void of a clear answer. Opinion corners are used to enable more able children to illustrate their thinking and to appreciate others ’thinking. Children are then supported to either maintain their view or on consideration of others thoughts, yield.

3. Circle time enquiries

The more formal enquiry model is used with more able learners, but has been carefully adapted to support young children’s thinking. An enquiry will take a week of 10 minute sessions daily and will begin with a stimulus. Children are supported to formulate a question and this can require a great deal of teacher support in the initial stages. We find in nursery that young children can find it challenging to formulate a question rather than a headline. This process may take two sessions. One question is then selected to pursue and the question quadrant supports how we will seek an answer.

The rest of the week will be taken with debating and exploring possible answers, and if the question is philosophical in its nature, our final reflection will support children’s acceptance of difference. The social behaviour within an enquiry is an essential element to the process. Respect for others when they are speaking and offering contributions to the group enquiry through gesture, form the parameters of collaboration.

4. Continuous provision

Within the continuous provision of our nursery classroom, Alfreton Nursery School provides specific stimulus for all children, linked to children’s literature. For example, during a focus on stories with a woodland theme, the keyword stimulus may be ‘Nature’. Artefacts and images supporting and challenging the meaning of nature will be available to support developing thinking. Over the course of the week, big, open-ended questions will be collected and displayed to support children’s engagement.

- ‘What is nature?’

- ‘Is nature at my house?’

- ‘Am I nature?’

- ‘Is nature in space?’

Talking, writing, drawing, singing, dancing, role play...are all encouraged as a means of responding to a stimulus.

Conclusion

P4C can be seen as a formal process, and with this assumption comes a belief that nursery children cannot engage fully in the pedagogy. Alfreton Nursery School refutes such a belief and can demonstrate that an enquiry based curriculum can provide nursery aged children with the freedom to form opinions and explore social influence. Young children need opportunities to reflect on their lived experience and feel exposure to wider concepts. P4C in nursery has powerful impact on children’s development as learners and grows individuals capable of critical and creative thinking within a culture of care and collaboration. All children benefit from a P4C approach, progressing rapidly across the whole curriculum, due to their increased capacity to question, respond to alternative perspectives and work together to solve problems.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Bob Cox,

05 October 2023

|

Is there really such a thing as a ‘greater depth’ pupil?

Is it educationally sound to create a 'greater depth’ group’ or is it a pragmatic way of responding to an assessment need?

I am going to argue the case that high potential pupils – and indeed all pupils – benefit most from an enriched English curriculum. Therefore, the terminology above – so widely used – may be misleading or even a barrier to the raising of standards.

The forming of a discrete ‘greater depth’ cohort raises a number of issues:

- when does a goal-orientated approach lapse into unhelpful labelling?

- have these pupils actually received enhanced provision which would make some sense of the rationale for selecting them?

- is there a lowering of aspiration for those not identified as advanced learners?

- how and when were they identified?

The answers to the above will vary from one context to another but as a big principle there are some huge pitfalls in identifying a fixed group:

- a plethora of bolt on extension tasks tend to emerge for them, some of which are never attempted as time runs out and some of which seem like extra work rather than deeper thinking.

- fixed views of pupils can take root long term.

- The route to ‘greater depth’ can become assessment driven but not involving quality reading, rich discussion or creativity. This can have an impact in key stage three where prior immersion in literary texts is likely to support access to high level challenge.

- Teachers also report high potential learners who become risk averse having established their position in a ‘greater depth’ group but not necessarily received ambitious texts or delved into connections across concepts.

For those secondary English teachers finding barriers to a love of literature – with some pupils struggling, for example, to comprehend narrative poetry like ‘The Ancient Mariner’ - the solution partly lies in the need for immersion in complex texts in the primary phase. A narrow focus on an advanced learning group may not produce the enrichment needed for effective and dynamic curriculum transition; and it certainly doesn’t support the aspirations of those outside a select group.

The recent DfE Reading Framework makes many comments about the need for challenging texts for all.

The text for a reading lesson can be more challenging than a pupil might be able to understand independently because the teacher is there to support comprehension, explaining the meaning of words and phrases or elaborating on key ideas. Teachers and English leads should also consider the relationship between the texts selected across the whole of the key stage and beyond to check that they are sequenced carefully and equip pupils with the ability to understand increasingly complex texts they may meet in later key stages.

So, to build a truly enriched curriculum, with equity and excellence at its heart, here are some suggestions of ways in which our UK network of schools have applied theory to practice and made ambitious English a reality, though always a work in progress:

- Explore a vision for enrichment across the staff. At its heart will be principles and strategies for pitching high but scaffolding and accessing for all. There has to be an agreed rationale for equity and excellence. It has to matter as a vision and a passion. The schools who apply this well have a deep belief in inclusion and social justice.

- Build a curriculum sequenced in difficulty with texts and objectives getting harder and linking to key stage 3. Avoid chasing assessment domains as a substitute for genuine curriculum progression and deeper knowledge and learning.

- Link in whole text reading to a core concept focus. So, if your poem or extract teaches ‘building suspense’ then plan for a range of readability to deepen the learning from picturebooks, through contemporary children’s literature to the classics. That way, all pupils read more quality texts as appropriate.

- Teach the concept in stages with visual literacy offering a gateway to rich language and the understanding of inference. Use a fascinating sentence, then a sliver of text, then a longer section. Complexity is the friend of both teacher and pupil – there is more to discover and so many questions to ask!

- Use taster drafts freely. Reading for writing makes a huge impact with time or word limited tasters introduced early in the process. The chance to imitate, invent, experiment and gain from feedback has been very popular for all pupils.

- Plan from the top and beyond the top. Think of where your most advanced learner might reach to in standard and use texts of such virtuosity and complexity that learning is a healthy struggle.

- Access strategies-like the tasters, the knowledge chunking, ranges of questions and the concept approach – provide ways in which all pupils share the curriculum entitlement and are being taught via deep learning dialogues inspired by great writing.

- Poetry can be at the centre of the English curriculum as the scope for being immersed in stylistic variation is at its greatest.

Teaching is adapted to need, not pre-programmed. High potential learners will be grown and nurtured cognitively, gaining in resilience, not blunted with fixed expectations. They will also have opportunities to learn how to get unstuck because they will need to reflect on conundrums and writing challenges as a daily habit.

You can find out much more by browsing through the ‘Opening Doors’ series by Bob Cox et al. There are books for key stages 1,2 and 3. The latest book is Opening Doors to Ambitious Primary English by Bob Cox with co-authors Leah Crawford, Julie Sargent and Angela Jenkins.

www.searchingforexcellence.co.uk

Contact Bob Cox on bobcox@searchingforexcellence.co.uk to find out more or ask for a visit to an ‘opening doors’ school.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

07 July 2023

Updated: 06 July 2023

|

Planning assessment using oral questions

Questioning, dialogic discourse and oracy are recognised as important aspects of teaching and learning but we must not forget that they are also important features of assessment. Questioning is routinely used as a formative assessment strategy. The teacher asks questions to establish whether pupils understand the content being shared. Misconceptions can be identified, and progress can be measured. The teacher can then make an appropriate learning decision and guide pupils to achieve the objectives.

Within a cognitively challenging learning environment the planning for teaching and assessment will include questions designed to not only to achieve these purposes but also to deepen, challenge and inspire learning. To develop assessment practices which support cognitively challenging learning the teacher must consider the nature of the questions being asked and their position within the lesson.

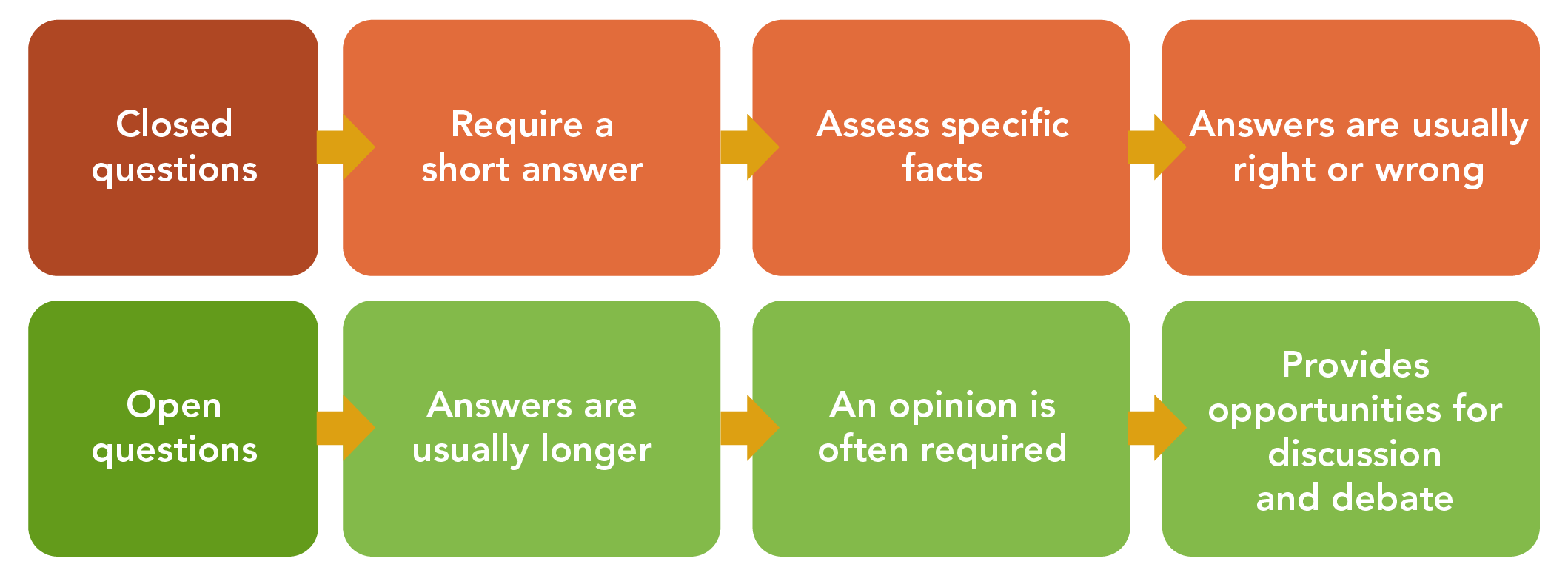

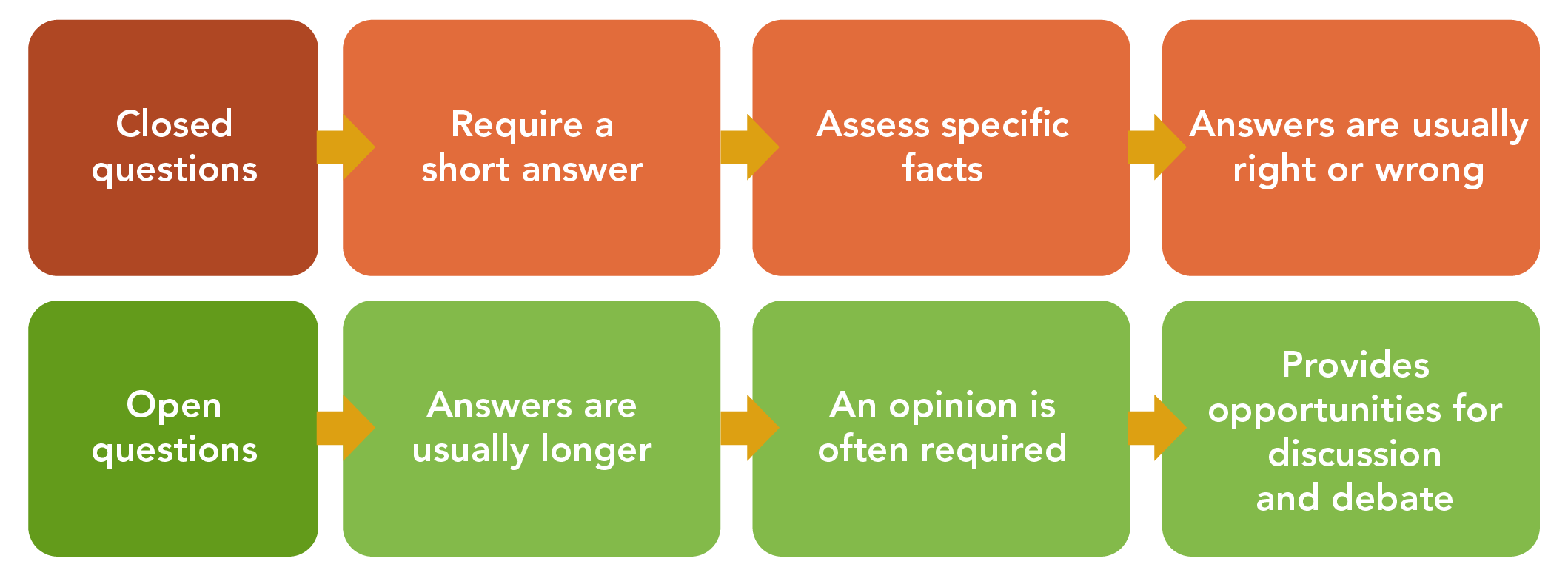

Teachers often use closed questions which require a specific response enables the teacher to assess whether specific facts are remembered. Closed questioning may include:

- quick fire questions (hands up response)

- peppered questions (quick retrieval around the class no hands up)

- call and response (ritual and repetition, response in unison)

- whole class response (possibly using white boards)

It is important for all pupils and particularly more able pupils to have a wide repertoire of knowledge and skills. By using these ongoing low stakes assessments pupils develop their knowledge recall and memory. The disadvantage of closed questions when working with more able pupils is that they often distract from the learning and take place when deeper learning is possible. The teacher must therefore plan carefully for these and have a good understanding of the needs of the class so that the questions are perceived positively within the learning and lead to benefits for the pupils.

By contrast open questions provide opportunities for healthy discussions and debate. Open-ended questions add interest to the lesson; challenging the pupils and enhancing thinking. The teacher can use these to check understanding, gain a fresh perspective on pupils’ learning and promote cognition.

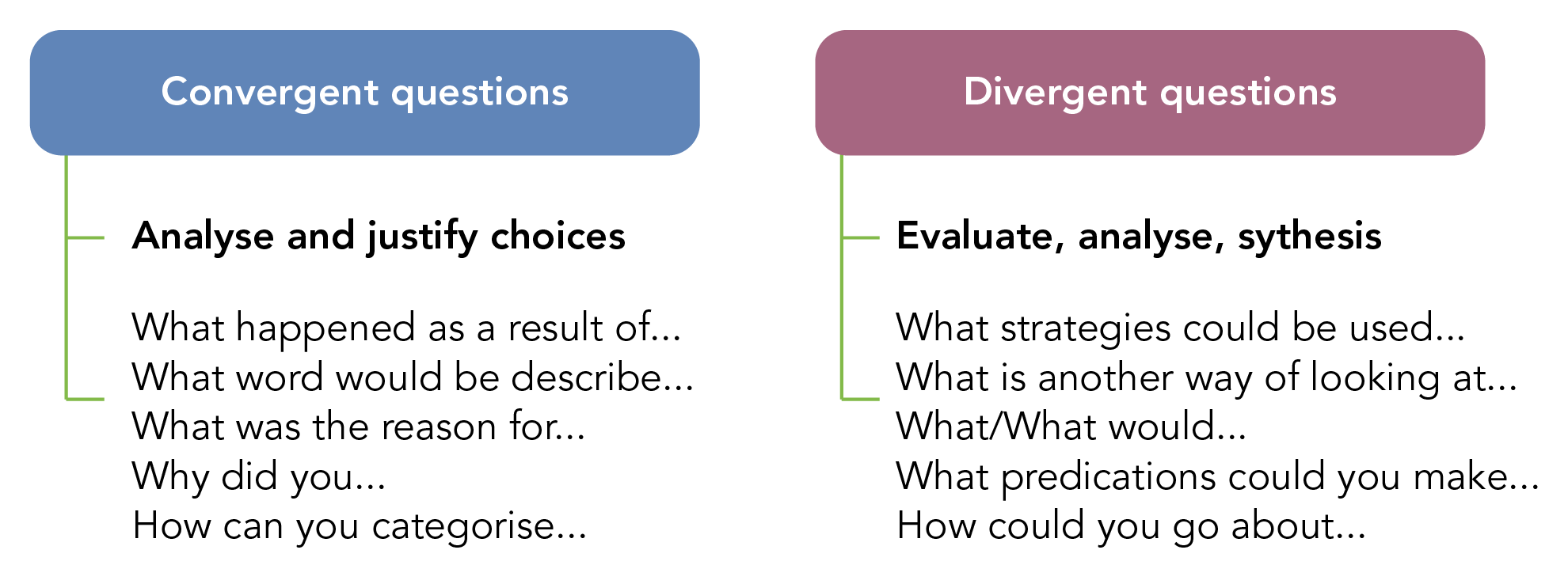

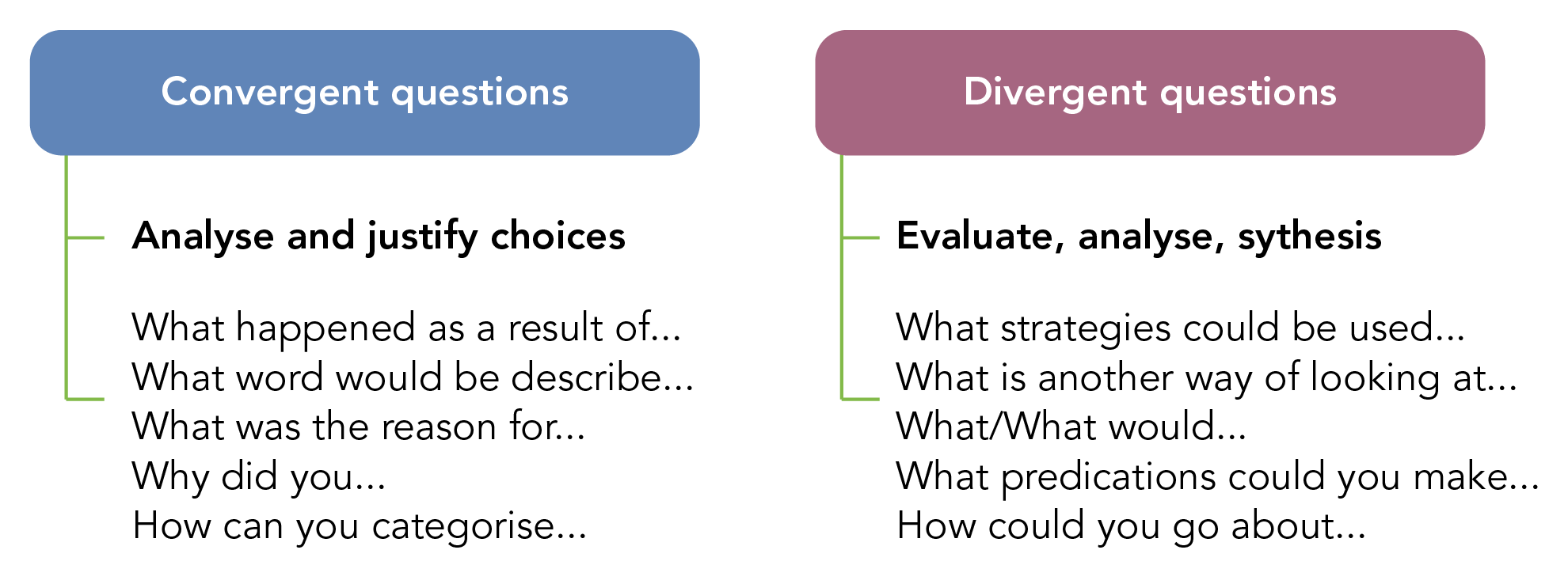

If pupils need to bring together ideas to solve problems then convergent questioning may be used. At the start of a lesson or topic the convergent question might be used to assess existing knowledge and understanding. To encourage convergent thinking the teacher may ask pupils to analyse different types of solution and justify their choice of the most appropriate solution. By contrast a teacher wishing to assess higher order cognitive learning such as evaluation, analysis or synthesis may use divergent questions.

One type of divergent question which is often used to both teach and assess learning is the “BIG QUESTION”. Using this, the teacher opens the learning up to include greater breadth and depth. A Big Question has the potential to promote independent learning through research and shared knowledge. A teacher may use this type of question to enable pupils to move beyond the planned content and introduce their own experience and interests. Alternatively, the question may be devised to provide cognitive challenge and to help pupils to organise the knowledge they already possess. Although this style of questioning is often viewed as a teaching tool it cannot be successful without ongoing assessment, review and refinement.

The use of questioning as an assessment technique not only requires an appropriate choice of question type but a careful consideration of how and when a question might be used. In the context of spoken questions, the teacher must decide at what point in the learning process the questions can provide most information about the learning and have the greatest impact on learning.

The teacher might pose questions from the front of the class, set questions which promote whole class or group dialogic discourse or pose individual questions. When a teacher poses questions to the whole class there is a risk that more able pupils answer a disproportionate number of questions or remain passive when there is little cognitive challenge. This can be addressed by promoting shared discussion through think-pair-share techniques. When the teacher decides to question the whole class, challenge can be achieved by asking questions which require pupils to continuously improve responses by asking pupils to say it again but better.

Once questioning techniques have become well established they not only provide a means of formative assessment but also enable assessment to become part of the learning process. The questions asked at the start of a programme of study or at the beginning of the lesson provide a baseline for instruction. Teachers know what the pupils can remember and how well they use their knowledge. The lesson can be adapted to reflect the starting point and the additional support needed. Teachers may be able to use a cutaway model for teaching so that those who need additional input can receive this. Other pupils who have been assessed as ready for more independent learning can undertake alternative, meaningful and challenging tasks working alone, in pairs or in small groups.

Questions strategically placed as a part of the delivery of the lesson can allow the teacher to moderate the pace of the lesson and the depth of learning. In classrooms where the teacher models good questioning, speaking and listening, pupils will learn to ask questions which help them to assess their own understanding and learn well.

Questions at the end of a period of learning act as an assessment of learning so that the teacher and pupils can establish what has been learnt and understood. Following written assessment teachers provide their pupils with feedback. This is often most effective when there is some degree of whole class feedback in which both the teacher and the pupils can ask deeper questions which allow the work to be improved and learning to be deepened.

The importance of discourse as an assessment tool

When a teacher poses questions to individual pupils, groups of pupils or to the class there is a clear link to the process of instruction and the demands od end of programme assessments and examinations. The teacher wishes to be sure that pupils have the knowledge and understanding of curriculum content and the ability to apply these in a variety of contexts.

For teachers of high ability pupils or pupils who have knowledge and skills in specific areas of learning this can provide limitations as there are a bounded number of questions and responses planned within the learning. Many teachers feel nervous when discussion goes beyond the predetermined lesson or curriculum plan. They may have concerns that course content will not be completed or that the pupils may deviate into areas where the teacher’s knowledge base is less secure.

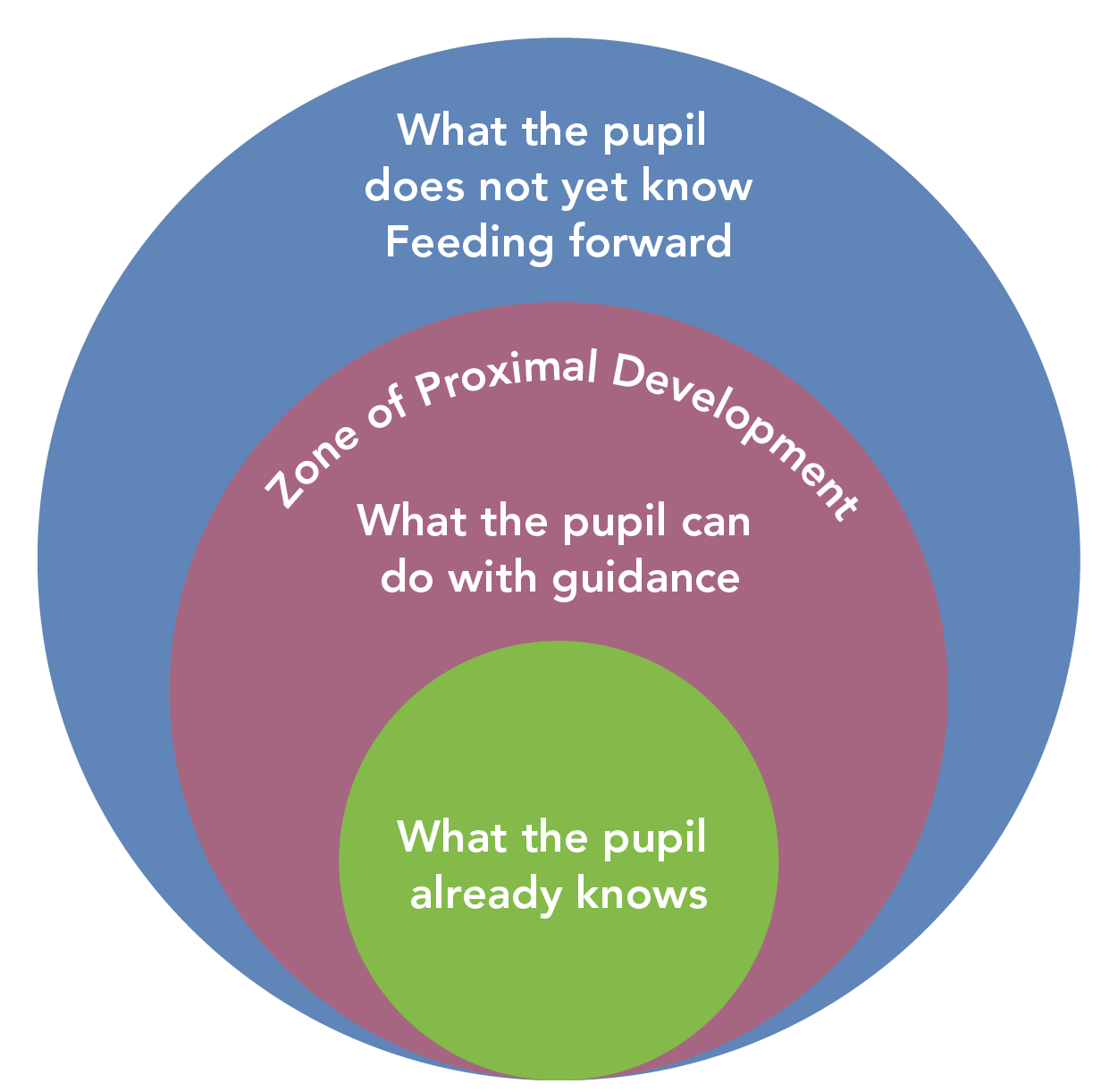

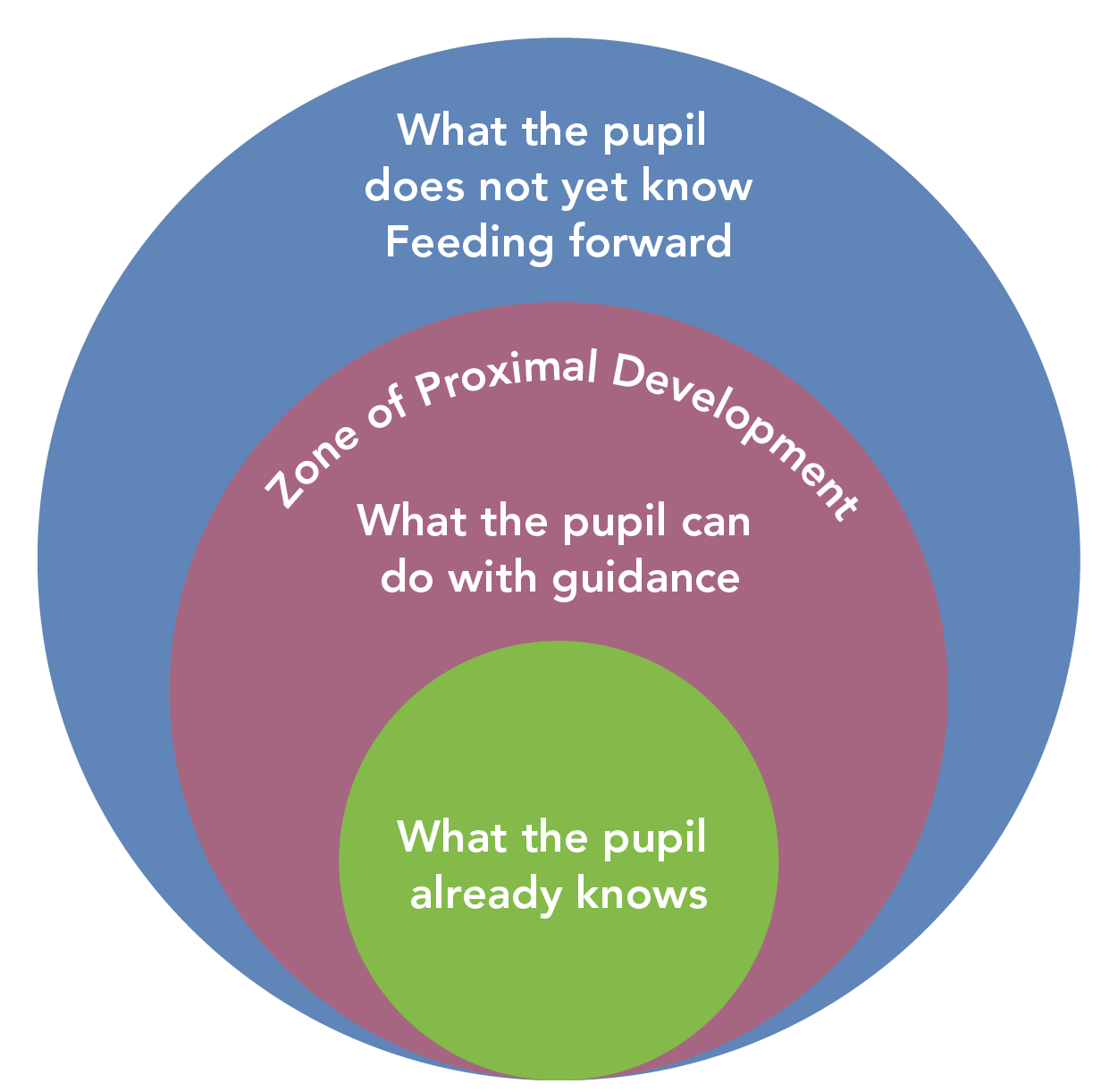

Vygotsky (1878) demonstrated the importance of language on learning. If the teacher has successfully assessed what the pupil already knows then the plan for learning takes place in the Zone of Proximal Development Pupils’ learning can be extended through interaction with others. He believed that giving a pupil appropriate assistance would be enough to achieve the task. This may be applied generally to pupils of all abilities but can be used specifically with high attainers or those underachieving but capable of high attainment.

Using this model teachers focus on three components to aid learning:

- The pupils are in the presence of someone more knowledgeable on the subject;

- The teacher uses social interaction skilfully, to allow pupils to observe and practice skills;

- Scaffolding or supportive activities with the teacher or peers support the pupil through the zone of proximal development.

Through assessment the teacher will establish what the pupil already knows. Pupils can then work alongside others who may have greater knowledge relating to aspects of a subject. Through classroom discussion they will be able to assess what they know themselves and gain new knowledge and understanding from those around them. When considering this as part of assessment strategies pupils will benefit from good quality feedback. Pupils need to know what a good response might look like. They need opportunities within classroom discourse to examine their own responses, share their views with other and make potential improvements to learning. Scaffolding and feeding forward enables pupils to use the feedback information effectively. During the subsequent classroom discourse they can ask questions or learn about aspects of the subject which are yet to be met formally as part of the learning process. By feeding forward more able pupils can make links in learning and think more deeply about what they are learning.

Through classroom discussion pupils can achieve more than they think themselves capable of learning. Pupils can develop multiple solution pathways to complex problems. By talking and working with the teacher and others they can attempt to solve interesting and challenging problems entering an initial zone of confusion with resilience. For this to be successful assessment strategies must be well developed. The teacher must know when to prompt, when to scaffold, when to ask a specific question or provide an idea. The teacher will also plan the preparatory work or materials needed to support discourse and have a means of measuring and evaluating the nature and quality of the discourse so that it leads to deep and rewarding learning.

What has been happening in our schools?

NACE schools can provide many good examples of questioning, dialogic discourse and improved oracy used effectively both as a teaching and as an assessment tool.

One example of practice which was being trialled in some schools was the use of the Harkness method. This method which originates in the Phillips Exeter Academy, New Hampshire and named after philanthropist Edward Harkness. It was developed to kindle curiosity, encourage learning and develop respect. Pupils sit in an oval and are encouraged to initiate and lead discussions about a designated text or area of learning. Pupils can develop ideas around a topic, ask questions and share their knowledge. The teacher is then able to assess the nature and quality of input from each of the pupils and the impact prior learning may have on their contributions. Examples of the use of this ranged from younger pupils bringing LAMDA skills into normal classroom learning and the teacher recording their behaviours on post it notes to sixth form students preparing and discussing materials in preparation for A level. The discussion diagram included the location of each pupil and a line joining pupils to those they spoke to. As can be seen, the teachers’ assessment tool can be diagrammatic allowing them to measure the frequency of contribution by each pupil and the nature of the contribution. The teacher facilitates the discussion but does not lead it. Where pupils’ lack knowledge or skills the teacher may separately support these. This is a good example of learning in the Zone of Proximal Development with ongoing assessment in place.

Another example of discourse leading to improved learning was the use of more able peer mentoring with younger pupils. Here the older pupils were metacognitively well developed and were able to assess the learning needs required to succeed in each subject. They were then able to enter discussion with younger pupils to advise and support them to develop learning attributes. The younger pupils learning from the more knowledgeable older pupils.

School leaders have also been thinking about the language we use when providing feedback and the time given to pupils to respond to that feedback. Often a feedback question leads to activity but does not necessarily deepen or enhance the quality of the learning and understanding. If the teacher demonstrates expectations and provides models which pupils can aspire to then the feedback question acquires greater meaning. Pupils might be asked to think more deeply about a response, include additional information, make comparisons, draw conclusions, make choices or express opinions. They may be asked to demonstrate a process or show alternative methods. Greater complexity or depth of response may be sought. When pupils receive this type of feedback they can then ask the teacher questions or engage in discussions together so that they bring greater knowledge and insight to their work developing their metacognition and metacognitive skills which they can use in the future. Leaders making changes to marking policy found that they needed to create space for learning in this way within the curriculum plan.

This post has not been tagged.

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

17 April 2023

Updated: 17 April 2023

|

NACE Associate Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Challenge Award-accredited Alfreton Nursery School, explains why and how environmental education has become an integral part of provision in her early years setting.

1. What’s the intent?

The ethics of teaching children of all ages about sustainability is clear. However, teaching such big concepts with such small children needs careful thought. The intention at Alfreton Nursery School is to stimulate an enquiring mind and to nurture children to believe in a solutions-based future.

Exposure to climate change from an adult perspective is dripping into our children’s awareness all the time. At Alfreton Nursery School we believe it is so important to take the current climate and give children a voice and a role within it. The invincibility of the early years mindset has been harnessed, with playful impact.

2. How do I implement environmental education with four-year-olds?

Environment

Just as an effective school environment supports children’s mathematical, creative (etc) development, so our environment at Alfreton is used to educate children on the value of nature. The resources we use are as ethically made and resourced as possible. We use recycled materials and recycled furniture, and lights are on sensors to reduce power consumption.

Like many schools, we have adapted our environment to work with the needs of the planet, and at Alfreton we make our choices explicit for the children. We talk about why the lights don’t stay on all the time, why we have a bicycle parking area in the carpark and why we are sitting on wooden logs, rather than plastic chairs. Our indoor spaces are sprinkled with beautiful large plants, adding to air quality, aesthetics and a sense of nature being a part of us, rather than separate. Incidental conversations about the interdependence of life on our planet feed into daily interactions.

Our biophilic approach to the school environment supports wellbeing and mental health for all, as well as supporting the education of our future generations.

Continuous provision and enhancements

Within continuous provision, resources are carefully selected to enhance understanding of materials and environmental impact. We have not discarded all plastic resources and sent them to landfill. Instead we have integrated them with newer ethical purchasing and take the opportunity to talk and debate with children. Real food is used for baking and food education, not for role play. Taking a balanced approach to the use of food in education feels like the respectful thing to do, as many of our families exist in a climate of poverty.

Larger concepts around deforestation, climate change and pollution are taught in many ways. Our provision for more able learners is one way we expand children’s understanding. In the Aspiration Group children are taught about the world in which they live and supported to understand their responsibilities. We look at ecosystems and explore human impact, whilst finding collaborative solutions to protect animals in their habitats. Through Forest Schools children learn the need to respect the woodlands. Story and reference literature is used to stimulate empathy and enquiry, whilst home-school partnerships further develop the connections we share with community projects to support nature.

We have an outdoor STEM Hive dedicated to environmental education. Within this space we have role play, maths, engineering, small world, science, music… but the thread which runs through this area is impact on the planet. When engaged with train play, we talk about pollution and shared transport solutions. When playing in the outdoor house we discuss where food comes from and carbon footprints. In the Philosophy for Children area we debate concepts like ‘fairness’ – for me, you, others and the planet. And on boards erected in the Hive there are images of how humans have taken the lead from nature. For example, in the engineering area there are images of manmade bridges and dams, along with images of beavers building and ants linking their bodies to bridge rivers.

3. Where will I see the impact?

Our environmental work in school has supported the progression of children across the curriculum, supporting achievements towards the following goals:

Personal, Social and Emotional Development:

- Show resilience and perseverance in the face of challenge

- Express their feelings and consider the feelings of others

Understanding the World:

- Begin to understand the need to respect and care for the natural environment and all living things

- Explore the natural world around them

- Recognise some environments that are different from the one in which they live

(Development Matters, 2021, DfE)

More widely, children are thinking beyond their everyday lived experience and connecting their lives to others globally. Our work is based on high aspirations and a passionate belief in the limitless capacity of young children. Drawing on the synthesis of emotion and cognition ensures learning is lifelong. The critical development of their relational understanding of self to the natural world has seen children’s mental health improve and enabled them to see themselves as powerful contributors, with collective responsibilities, for the world in which they live and grow.

Read more:

Plus:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

early years foundation stage

pedagogy

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Trellech Primary School,

17 April 2023

Updated: 17 April 2023

|

Kate Peacock, Acting Headteacher at Trellech Primary School, explains how “SMILE books” have been introduced to develop pupil voice and independent learning, while also improving staff planning.

Our vision, here at Trellech Primary, is to ensure the four purposes of the Curriculum for Wales are at the heart of our children’s learning – particularly ensuring that they are “ambitious capable learners” who:

- Set themselves high standards and seek and enjoy challenge;

- Are building up a body of knowledge and have the skills to connect and apply that knowledge in different contexts;

- Are questioning and enjoy solving problems.

What is a “SMILE Curriculum”?

We have always been very proud of the children at Trellech Primary, where we see year on year pupils making good progress in all areas of the curriculum. Following the publication of Successful Futures and curriculum reform in Wales, the school wanted to embrace the changes and be forward-thinking in recognising and nurturing children as learners who are responsible for planning and developing their own learning. As a Pioneer School, we made a commitment to:

- Give high priority to pupil voice in developing their own learning journey.

- Develop pupil voice throughout each year group, key stage and the whole school.

- Embrace the curriculum reform and develop children’s understanding.

- Allow all learners to excel and reach their full potential.

- Ensure each child is given the opportunity to make good progress.

These goals have been developed alongside the introduction of SMILE books, based on our SMILE five-a-day culture:

- Standards

- Modelled behaviour

- Inspiration

- Listening

- Ethical

What is a “SMILE book”?

Based on these key values of the SMILE curriculum, the SMILE books are A3-sized, blank-paged workbooks which learners can use to present their work however they choose. They are used to present the children’s personal learning journey. In contrast to the use of books for subject areas, SMILE books show the development of skills from across the Areas of Learning and Experience (AoLEs) in their own preferred style.

This format enables pupil voice to be at the fore of their journey, while clearly promoting each pupil’s independent learning and supporting individual learning styles. Within a class, each SMILE book will look different, despite the same themes being part of the teaching and learning. Some may be presented purely through illustration with relevant vocabulary, while others develop and present their learning through greater use of text.

Launching the SMILE books

As a Pioneer School we collaborated with colleagues who were at the same point of their curriculum journey as us. Following this collaboration, we agreed to trial the introduction of our SMILE books in Y2 and Y6 with staff who were members of SLT and involved in curriculum reform.

In these early stages, expectations were shared and pupils were given a variety of resources to enable them to present their work in their preferred format within the books – enabling all individuals to lead, manage and present their knowledge, skills and learning independently.

Pupil and parent feedback at Parent Sharing Sessions highlighted positive feedback and demonstrated pupils’ pride in the books. Consequently, SMILE books were introduced throughout the school at the start of the following academic year. For reception pupils scaffolding is provided, but as pupils move through the progression steps less scaffolding is needed; pupil independence increases and is clearly evident in the way work across the AoLEs is presented.

Staff SMILE planning

Following the success of the implementation of pupil SMILE books and to ensure clarity in understanding of the Curriculum for Wales, I decided to trial the SMILE book format myself, to record my planning. This helped me to develop greater depth of knowledge and understanding of the Four Purposes, Cross-Curricular Links, Pedagogical Principles and the What Matters Statements for each of the AoLEs.

During this early trial I wrote each of the planning pages by hand, which enabled me to internalise the curriculum with an increased understanding. Also included were the ideas page for each theme and pupil contributions through the pupil voice page.

This format was shared with the whole staff and has evolved over time. Some staff continue to write and present planning in a creative form, while others use QR codes to link planners to electronic planning sheets and class tracking documentation. The inclusion of the I Can Statements has enabled staff to delve deeper and focus on less but better.

Each SMILE medium-term planning book moves with the cohort of learners, exemplifying their learning journey through the school. The investment of time in medium-term planning enables staff to focus on skills development in short-term planning time. This is evident in the classroom, where lessons focus on skills development and teachers are seen as facilitators of learning.

Impact on teaching and learning

Following our NACE Challenge Award reaccreditation in July 2021, it was recognised that the use of SMILE books had a positive impact on pupil voice and the promotion of independent learning for all. Our assessor reported:

SMILE books, which the school considers to be at the heart of all learning, are used by all year groups. Children complete activities independently in their books showing their own way of learning and presenting their work in a range of styles and formats. As a result, even from the youngest of ages, pupils have become more independent learners who are engaged in their learning because they have been involved in the decision-making process for the topics being taught.

The SMILE approach to learning has strengthened pupil voice and given children the confidence to take risks in their own learning by choosing how they like to learn.

The SMILE approach to learning has created a climate of trust where learners are confident to take risks without the fear of failure and are valued for their efforts. Pupils appreciate that valuable learning often results from making mistakes.

SMILE promotes problem solving and enquiry-based activities to help nurture independent learning.

Using SMILE books, independent learning is promoted and encouraged from the youngest of ages. The SMILE approach encourages MAT learners to lead their own learning by equipping them with the skills and knowledge to know how they best learn. As a result, more able pupils are critical thinkers and have high expectations and aspirations for themselves.

Our SMILE approach continues to develop here at Trellech, ensuring the continual development of our learners and independent learners with a valued voice.

Explore NACE’s key resources for schools in Wales

Tags:

Challenge Award

creativity

curriculum

independent learning

professional development

student voice

Wales

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Jonathan Doherty,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

NACE Associate Dr Jonathan Doherty outlines the focus of this year’s NACE R&D Hub on “oracy for high achievement” – exploring the impetus for this, challenges for schools, and approaches being trialled.

This year one of the NACE Research & Development Hubs is examining the theme of ‘oracy for high achievement’. The Hub is exploring the importance of rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse in the context of shared classroom practice. School leaders and teachers participating in the Hub are seeking to improve the value and effectiveness of speaking and listening. They are developing a body of knowledge about provision and pedagogy for more able learners, sharing ideas and practice and contributing to wider research evidence on oracy through their classroom-based enquiries.

Why focus on oracy?

Oracy is one of the most used and most important skills in schools. To be able to speak eloquently and with confidence, to articulate thinking and express an opinion are all essential for success both at school and beyond. Communication is a vital skill for the 21st century from the early years, through formal education, to employment. It embraces skills for relationship building, resolving conflict, thinking and learning, and social interaction. Oral language is the medium through which children communicate formally and informally in classroom contexts and the cornerstone of thinking and learning. The NACE publication Making Space for Able Learners found that “central to most classroom practice is the quality of communication and the use of talk and language to develop thinking, knowledge and understanding” (NACE, 2020, p.38).

Oracy is very much at the heart of classroom practice: modern classroom environments resound to the sound of students talking: as a whole class, in group discussions and in partner conversations. Teachers explaining, demonstrating, instructing and coaching all involve the skills of oracy. Planned purposeful classroom talk supports learning in and across all subject areas, encouraging students to:

- Analyse and solve problems

- Receive, act and build upon answers

- Think critically

- Speculate and imagine

- Explore and evaluate ideas

Dialogic teaching’ is highly influential in oracy-rich classrooms (Alexander, 2004). It uses the power of classroom talk to challenge and stretch students. Through dialogue, teachers can gauge students’ perspectives, engage with their ideas and help them overcome misunderstandings. Exploratory talk is a powerful context for classroom talk, providing students with opportunities to share opinions and engage with peers (Mercer & Dawes, 2008). It is not just conversational talk, but talk for learning. Given the importance and prevalence of classroom talk, it would be easy to assume that oracy receives high status in the curriculum, but its promotion is not without obstacles to overcome.

Challenges for schools in developing oracy skills

Covid-19 has impacted upon students’ oracy. A report from the children’s communication charity I CAN estimated that more than 1.5 million UK young people risk being left behind in their language development as a result of lost learning in the Covid-19 period (read more here). The Charity reported that the majority of teachers were worried about young people being able to catch up with their speaking and understanding as a result of the pandemic (I CAN, 2021).

With origins going back to the 1960s, the term oracy was introduced as a response to the high priority placed on literacy in the curriculum of the time. Rien ne change, with the current emphasis remaining exactly so. Literacy skills, i.e. reading and writing, continue to dominate the curriculum. Oracy extends vocabulary and directly helps with learning to read. The educationalist James Nimmo Britton famously said that “good literacy floats on a sea of talk” and recognised that oracy is the foundation for literacy.

Teachers do place value on oracy. In a 2016 survey by Millard and Menzies of 900 teachers across the sector, over 50% said they model the sorts of spoken language they expect of their students, they do set expectations high, and they initiate pair or group activities in many lessons. They also highlighted the social and emotional benefits of oracy and suggested it has untapped potential to support pupils’ employability – but reported that provision is often patchy and that CPD was sparse or even non-existent.

Another challenge is that oracy is mentioned infrequently in inspection reports. An analysis of reports of over 3,000 schools on the Ofsted database, undertaken by the Centre for Education and Youth in 2021, found that when taken in the context of all school inspections taking place each year, oracy featured in only 8% of reports.

The issue of how oracy is assessed is a further challenge. Assessment profoundly influences student learning. Changes to assessment requirements now provide schools with new freedoms to ensure their assessment systems support pupils to achieve challenging outcomes. Despite useful frameworks to assess oracy such as the toolkit from the organisation Voice 21, there is no accepted system for the assessment of oracy.

What are NACE R&D Hub participants doing to develop oracy in their schools?

The challenges outlined above make the work of participants in the Hub of real importance. With a focus on ‘oracy for high achievement’, the Hub is supporting teachers and leaders to delve deeper into oracy practices in their classrooms. The Hub supports small-scale projects through which they can evidence the impact of change and evaluate their practice. Activities are trialled over a short period of time so that their true impact can be observed in school and even replicated in other schools.

The participants are now engaged in a variety of enquiry-based projects in their classrooms and schools. These include:

- Use of the Harkness Discussion method to enable more able students to exhibit greater depth of understanding, complexity of response and analytical skills within cognitively challenging learning;

- Explicit teaching of oracy skills to improve independent discussion in science and history lessons;

- Introduction of hot-seating to improve students’ ability to ask valuable questions;

- Choice in oral tasks to improve the quality of students’ analytical skills;

- Oracy structures in collaborative learning to challenge more able students’ deeper learning and analysis;

- Better reasoning using oracy skills in small group discussion activities;

- Interventions in drama to improve the quality of classroom discussion.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective oracy practices, including new initiatives and well-established practices. You may feel that some of the examples above are similar to practices in your own school, or you may have well-developed models of oracy teaching and learning that would be of interest to others. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- How can we implement effective oracy strategies without dramatically increasing teacher workload?

- How can we best develop oracy for the most able in mixed ability classrooms?

- What approaches are most effective in promoting oracy in group work so that it is productive and benefits all learners?

- How can we implicitly teach pupils to justify and expand their ideas and make clear opportunities to develop their understanding through talk and deepen their understanding?

- How do we evidence challenge for oracy within lessons?

Teachers should develop students’ spoken language, reading, writing and vocabulary as integral aspects of the teaching of every subject. Every teacher is a teacher of oracy. The report of the All-Party Parliamentary Group inquiry into oracy in schools concluded that there was an indisputable case for oracy as an integral aspect of education. This adds to a growing and now considerable body of evidence to celebrate the place that oracy has in our schools and in our society. Oracy is in a unique place to support the learning and development of more able pupils in schools and the time to give oracy its due is now.

References

- Alexander, R. J. (2004) Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. York, UK: Dialogos.

- Britton, J. (1970) Language and learning. London: Allen Lane. [2nd ed., 1992, Portsmouth NH: Boynton/Cook, Heinemann].

- I CAN (2021) Speaking Up for the Covid Generation. London: I CAN Charity.

- Lowe, H. & McCarthy, A. (2020) Making Space for Able Learners. Didcot, Oxford: NACE.

- Mercer, N. &. Dawes., L. (2008) The Value of Exploratory Talk. In Exploring Talk in School, edited by N. Mercer and S. Hodgkinson, pp. 55–71. London: Sage.

- Millard, W. & Menzies, L. (2016) The State of Speaking in Our Schools. London: Voice 21/LKMco.

- Millard, W., Menzies, L. & Stewart, G. (2021) Oracy after the pandemic: what Ofsted, teachers and young people think about oracy. Centre for Education & Youth/University of Oxford.

Read more:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

collaboration

confidence

CPD

critical thinking

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

policy

questioning

research

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Gianluca Raso,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

Gianluca Raso, Senior Middle Leader for MFL at NACE Challenge Award-accredited Maiden Erlegh School, explores the real meaning of “adaptive teaching” and what this means in practice.

When I first came across the term “adaptive teaching”, I thought: “Is that not what we already do? Surely, the label might be new, but it is still differentiation.” Monitoring progress, supporting underperforming students and providing the right challenge for more able learners: these are staples in our everyday practice to allow students to actively engage with and enjoy our subjects.

I was wrong. Adaptive teaching is not merely differentiation by another name. In adaptive teaching, differentiation does not occur by providing different handouts or the now outdated “all, most, some” objectives, which intrinsically create a glass ceiling in students’ achievement. Instead, it happens because of the high-quality teaching we put in for all our students.

Adaptive teaching is a focus of the Early Career Framework (DfE, 2019), the Teachers’ Standards, and Ofsted inspections. It involves setting the same ambitious goals for all students but providing different levels of support. This should be targeted depending on the students’ starting points, and if and when students are struggling.

But of course it is not as simple as saying, “this is what adaptive teaching means: now use it”.

So how, in practice, do we move from differentiation to adaptive teaching?

A sensible way to look at it is to consider adaptive teaching as an evolution of differentiation. It is high-quality teaching based on:

- Maintaining high standards, so that all learners have the opportunity to meet expectations.

Supporting all students to work towards the same goal but breaking the learning down – forget about differentiated or graded learning objectives.

- Balancing the input of new content so that learners master important concepts.

Giving the right amount of time to our students – mastery over coverage.

- Knowing your learners and providing targeted support.

Making use of well-designed resources and planning to connect new content with pupils' prior knowledge or providing additional pre-teaching if learners lack critical knowledge.

- Using Assessment for Learning in the classroom – in essence check, reflect and respond.

Creating assessment fit for purpose – moving away from solely end of unit assessments.

- Making effective use of teaching assistants.

Delivering high quality one-to-one and small group support using structured interventions.

In conclusion, adaptive teaching happens before the lesson, during the lesson and after the lesson.

Aim for the top, using scaffolding for those who need it. Consider: what is your endgame and how do you get there? Does everyone understand? How do you know that? Can everyone explain their understanding? What mechanisms have you put in place to check student understanding ? Encourage classroom discussions (pose, pause, pounce, bounce), use a progress checklist, question the students (hinge questions, retrieval practice), adapt your resources (remove words, simplify the text, include errors, add retrieval elements).

Adaptive teaching is a valuable approach, but we must seek to embed it within existing best practice. Consider what strikes you as the most captivating aspect of your curriculum in which you can enthusiastically and wisely lead the way .

Ask yourself:

- Could all children access this?

- Will all children be challenged by this?

… then go from there…

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

differentiation

feedback

pedagogy

professional development

progression

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|