Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

curriculum

oracy

independent learning

aspirations

cognitive challenge

free resources

KS3

KS4

language

critical thinking

assessment

English

literacy

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

creativity

vocabulary

wellbeing

access

lockdown

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Lauren Bellaera,

03 March 2021

|

Dr Lauren Bellaera is Director of Research and Impact at The Brilliant Club, a UK-based charity which aims to increase the number of pupils from under-represented backgrounds that progress to highly selective universities. In this blog post (originally published on The Learning Scientists website), Dr Bellaera explores research-informed approaches to develop critical thinking skills in the classroom – ahead of her forthcoming live webinar on this theme for NACE members (recording available to watch back when logged in as a member).

What is critical thinking?

Many definitions of critical thinking exist – far too many to list here! – but one key definition that is often used is:

“[the] purposeful, self-regulatory judgment which results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanation of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations upon which judgment is based” (1, p. 3).

Despite the different definitions, there is a consensus regarding the dimensions of critical thinking and these dimensions have implications for how critical thinking is understood and taught. Critical thinking includes skills and dispositions (1). The former refers to reasoning and logical thinking, e.g., analysis, evaluation, and interpretation, whereas the latter refers to the tendency to do something, e.g., being open-minded (2). This blog post primarily is referring to the development of critical thinking skills as opposed to dispositions.

Critical thinking can be subject-specific or general, and thus can either be embedded within a specific subject or it can be developed independently of subject knowledge – something that we will revisit later.

How are critical thinking skills developed?

Developing critical thinking is often regarded as the cornerstone of higher education, but the reality is that many educational institutions are failing to develop critical thinking consistently and reliably in their students, with only around 6% of university graduates considered proficient (3), (4), (5).

Thus, there is a disconnect between the value of critical thinking and the degree to which it is supported by effective instruction (6). So, what does effective instruction look like? Helpfully, cognitive psychology provides us with some of the answers:

1. Context is king: the importance of background knowledge

The important question at hand here is: are some types of critical thinking more difficult to develop than others? The short answer is yes – subject-specific critical thinking appears to be easier to develop than general critical thinking. Studies have shown that critical thinking interventions improve subject-specific as opposed to general critical thinking (7), (8). This is also what we have found in our own research (9).

Possible reasons for why this is the case include the fact that the length of time needed to develop general critical thinking is much greater. This is coupled with the idea that general critical thinking is simply not as malleable as subject-specific critical thinking (10). For balance, though, some studies have reported improvements in general critical thinking, indicating that under the right circumstances, general improvement is possible (6), (11). The key message here is that background knowledge is an important part of teaching critical thinking and the extent to which you aim to develop critical thinking beyond the scope of the course content should be assessed dependent on what is achievable in the given context.

2. Be explicit: approaches to critical thinking instruction

The importance of background knowledge also has implications for critical thinking instruction (12). There are four main approaches to critical thinking instruction; general, infusion, immersion and mixed (13):

The general approach explicitly teaches critical thinking as a separate course outside of a specific subject. Content can be used to structure examples and activities but it is not related to subject-specific knowledge and tends to be about everyday events.

The infusion approach explicitly teaches both subject content and general critical thinking skills, where the critical thinking instruction is taught in the context of a specific subject.

Similarly, the immersion approach also teaches critical thinking within a specific subject, but it is taught implicitly as opposed to explicitly. This approach infers that critical thinking will be a consequence of interacting with and learning about the subject matter.

Lastly, the mixed approach is an amalgamation of the above three approaches where critical thinking is taught as a general subject alongside either the infusion or immersion approach in the context of a specific subject.

In terms of which are the best instructional approaches to adopt, evidence from a meta-analysis of over 100 studies showed that explicit approaches led to the greatest increase in critical thinking compared to implicit approaches. Specifically, the mixed approach where critical thinking was taught explicitly as a separate strand and within a specific subject was the most effective, whereas the implicit immersion approach was the least effective. This research suggests that developing critical thinking skills separately and then applying them to subject content explicitly works best (14).

3. Be strategic: effective teaching strategies

The knowledge that critical thinking needs to be deliberately and explicitly built into courses is integral to developing critical thinking. However, without the more granular details of exactly what teaching strategies sit beneath this, it will only get us so far. A number of teaching strategies have been shown to be effective, including the following:

Both answering and generating higher-order thinking questions have been shown to increase critical thinking (8) (14). For example, psychology students who were given higher-order thinking questions compared to lower-order thinking questions significantly improved their subject-specific critical thinking (8). Alison King’s work on higher-order questions provides some useful examples of question stems (15).

Ensuring that critical thinking is anchored in authentic instruction that allows students to engage with problems that make sense to them, and that enables further inquiry, is important (6). Some ways to facilitate authentic instruction include simulations and applied problem solving.

Closely related to higher-order questions and authentic instruction is dialogue – essentially discussions are needed to develop critical thinking. Teachers asking questions is particularly beneficial to the development of critical thinking, in part because teachers will often be asking questions that require higher-order thinking. A meta-analysis study showed that authentic instruction and dialogue were particularly effective for developing general critical thinking (6).

Engaging pupils in explicit self-reflection techniques promotes critical thinking. For example, asking students to judge their performance on a paper can increase their ability to understand where they need to improve and develop in the future (16). Other formalisations of this include reflection journals (17). In my current role, we also employ self-reflection activities to increase critical thinking.

So, to conclude, remember when developing critical thinking skills that context is king, always be explicit and always be strategic!

Find out more… On 29 April 2021 Dr Bellaera presented a live webinar for NACE members exploring the research on critical thinking and how to apply it in your school. Watch the recording here (login required). Plus: Dr Bellaera's research paper on critical thinking is available to read and download here until 4 August 2021.

References:

(1) Facione, P. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction (The Delphi Report).

(2) Ennis, R. H. (1996). Critical thinking. Upper-Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

(3) American Association of Colleges and Universities (2005). Liberal education outcomes: Preliminary report on student achievement in college. Washington, DC: AAC&U.

(4) Dunne, G. (2015). Beyond critical thinking to critical being: Criticality in higher education and life. International Journal of Educational Research, 71, 86-99.

(5) Ku, K. Y. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 4, 70- 76.

(6) Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D. I., Wade, C. A., & Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for teaching students to think critically: a meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85, 275-314.

(7) Williams, R. L., Oliver, R., & Stockdale, S. (2004). Psychological versus academic critical thinking as predictors and outcome measures in a large undergraduate human development course. The Journal of General Education, 53, 37-58.

(8) Renaud, R. D., & Murray, H. G. (2008). A comparison of a subject-specific and a general measure of critical thinking. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 3, 85-93.

(9) Bellaera, L., Debney, L., & Baker, S. (2018). An intervention for subject comprehension and critical thinking in mixed academic ability university students. The Journal of General Education.

(10) Facione, P. A., Facione, N. C, & Giancarlo, C. A. (2000). The disposition toward critical thinking: Its character, measurement, and relationship to critical thinking skill. Informal Logic, 20, 61-84.

(11) Halpern, D. F. (2001) Assessing the effectiveness of critical thinking instruction. The Journal of General Education, 50, 270–286.

(12) Lai, E. R. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review. Pearson's Research Reports, 6, 1-49.

(13) Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research. Educational Researcher, 18, 4-10.

(14) Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78, 1102-1134.

(15) King, A. (1995). Designing the instructional process to enhance critical thinking across the curriculum. Teaching of Psychology, 22, 13-17.

(16) Austin, Z., Gregory, P. A., & Chiu, S. (2008). Use of reflection-in-action and self-assessment to promote critical thinking among pharmacy students. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 72, 1-8.

(17) Mannion, J., & Mercer, N. (2016). Learning to learn: Improving attainment, closing the gap at Key Stage 3. The Curriculum Journal, 27, 246-271.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

metac

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Emma Sanderson,

12 January 2021

|

Emma Sanderson, Head of English at NACE member and Challenge Award-accredited Hartland International School (Dubai), shares advice for successful use of “Genius Hour” project-based learning to challenge and motivate learners, inspired by Google’s “20% time”.

As teachers, our awareness of the importance of challenging questions is always at the forefront of our minds, particularly with our more able learners. However, the onus of asking challenging questions shouldn’t always be placed on the teacher. Cue Genius Hour, an idea inspired by Google’s “20% time”, in which employees are encouraged to spend 20% of their time working on any project of their choosing, on the condition that it ultimately benefits the company in some way, and which is famously credited with giving rise to many of Google’s most successful innovations.

Google’s “20% time” is similar to the use of Genius Hour in our school: encouraging students to take ownership of their learning by using a proportion of curriculum time to focus on topics they are passionate about. By coming up with their own driving question to focus their research, students manage their own learning journey and subsequently become even more engaged with the learning process.

Here are three key steps to use Genius Hour project-based learning effectively:

1) Support students to develop their driving question.

The driving question of the project will become the focus of the students’ research. Whilst students may be tempted to simply find out more information about a topic close to their heart, the key is to construct a question that allows for in-depth research and is also broad enough for students to include their personal opinions. Even our most able learners will need support with this task, and for this, question stems can be incredibly useful:

- What does _______ reveal about _________?

- To what extent does…?

- What motivates_________?

- How would you develop…?

- What alternatives are there for…?

- How can technology be used to…?

- What assumptions are there about…?

- What are the [ethical] implications of…?

- How can we challenge…?

- What would happen if…?

- How can we improve…?

- What might happen if…?

Students might be encouraged to come up with solutions to real-life problems or delve into ideas linked to current affairs that they are intrigued by. Either way, these broad question stems allow for thorough exploration of a topic.

2) Help students develop their research skills.

Left to their own devices, students may be tempted to simply Google their question and see what answers come up. Instead, offer guidance on the best and most reliable sources of information for their project.

It may be that students are directed towards relevant reference books in the library. Additionally, online resources can prove invaluable; the Encyclopaedia Britannica offers a wealth of knowledge for students, whilst news websites aimed at teenagers (for example Newsela and The Day) encourage students to form their own opinions on current affairs and offer suggestions for further reading.

Our more able learners may be more adept at focusing their internet searches and filtering through the vast array of results. If this is the case, students would be expected to determine whether a source is reliable or biased and should be confident at citing their sources.

3) Encourage creativity in how students present their findings.

Ideally, students will be excited and motivated to complete their Genius Hour project, and originality in how they present their results should be encouraged. Students may want to create a video, make a presentation, write a passionate and persuasive speech, design an informative leaflet… The more freedom the students have, the more their creativity will flourish.

One of our students gave a rousing speech on the question, “What alternatives are there to living on planet Earth?” (ultimately concluding there were none and that we need to change our lifestyles in order to save the planet). Another offered a passionate presentation on the theme “How can we improve Earth’s biodiversity while allowing people to still eat meat and plants?” And after witnessing the impact of Covid-19 first hand, one student wrote an insightful article to answer the question, “What has Covid-19 revealed about our society in 2020?”

This approach to project-based learning can also be effectively applied during distance learning – students can be given the success criteria for the project and set the challenge of managing their own time. There is ample opportunity to use technology to give presentations remotely, either live through Zoom or Teams, or recorded individually using a platform such as Flipgrid.

In summary…

Overall, Genius Hour is a fantastic tool to promote deeper thinking in the classroom, whilst also having huge benefits across the wider curriculum. We have found this approach has worked particularly well with Key Stage 3 students and is the perfect opportunity to refine the research and presentation skills required at GCSE, whilst also impacting positively across the curriculum in all lessons. Furthermore, it sends the message to students that their passions outside of school are valued, which in itself can prove to be hugely motivational. Presenting their findings at the end of the project instils confidence in our learners, giving them the vital communication, leadership and time management skills necessary for life beyond education.

Further reading: “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”

NACE’s report “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice” explores approaches to curriculum and pedagogy which optimise the engagement, learning and achievement of very able young people, combining relevant research and theory with examples of current practice in NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools. Preview and order here.

Not yet a NACE member? Find out more, and join our mailing list for free updates and free sample resources.

Tags:

confidence

creativity

enquiry

enrichment

independent learning

motivation

problem-solving

project-based learning

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

17 November 2020

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Associate and co-author of NACE’s new publication “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”.

When you’re planning a lesson, are your first thoughts about content, resources and activities, or do you begin by thinking about learning and cognitive challenge? How often do you consider lessons from the viewpoint of your more able pupils? Highly able pupils often seek out cognitively challenging work and can become distressed or disengaged if they are set tasks which are constantly too easy.

NACE’s new research publication, “ Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”, marks the first phase in our “Making Space for Able Learners” project. Developed in partnership with NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools, the research examines the impact of cognitive challenge in current school practice against a backdrop of relevant research. What do we mean by ‘cognitive challenge’?

Cognitive challenge can be summarised as an approach to curriculum and pedagogy which focuses on optimising the engagement, learning and achievement of highly able children. The term is used by NACE to describe how learners become able to understand and form complex and abstract ideas and solve problems. Cognitive challenge prompts and stimulates extended and strategic thinking, as well as analytical and evaluative processes.

To provide highly able pupils with the degree of challenge that will allow them to flourish, we need to build our planning and practice on a solid foundation.

This involves understanding both the nature of our pupils as learners and the learning opportunities we’re providing. When we use “challenge” as a routine, learning will be extended at specific times on specific topics – which has useful but limited benefit. However, by strategically building cognitive challenge into your teaching, pupils’ learning expertise, their appetite for learning and their wellbeing will all improve.

What does this look like in practice?

The research identified three core areas:

1. Design and management of cognitively challenging learning opportunities

In the most successful “cognitive challenge” schools, leaders have a clear vision and ambition for pupils, which explicitly reflects an understanding of teaching more able pupils in different contexts and the wider benefits of this for all pupils. This vision is implemented consistently across the school. All teachers engage with the culture and promote it in their own classrooms, involving pupils in their own learning. When you walk into any classroom in the school, pupils are working to the same model and expectation, with a shared understanding of what they need to do.

Pupils are able to take control of their learning and become more self-regulatory in their behaviours and increasingly autonomous in their learning. Through intentional and well-planned management of teaching and learning, children move from being recipients in the learning environment to effective learners who can call on the resources and challenges presented. They understand more about their own learning and develop their curiosity and creativity by extending and deepening their understanding and knowledge.

2. Rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse to support cognitive challenge

The importance of questions and questioning in effective learning is well understood, but the importance of depth and complexity of questioning is perhaps less so. When you plan purposeful, stimulating and probing questions, it gives pupils the freedom to develop their thought processes and challenge, engage and deepen their understanding. Initially the teacher may ask questions, but through modelling high-order questioning techniques, pupils in turn can ask questions which expose new ways of thinking.

This so-called “dialogic teaching” frames teaching and learning within the perspective of pupils and enhances learning by encouraging children to develop their thinking and use their understanding to support their learning. Initially, pupils might use the knowledge the teacher has given them, but when they’re shown how to use classroom discourse effectively, they’ll start to work alone, with others or with the teacher to extend their repertoire.

By using an enquiry-orientated approach, you can more actively engage children in the production of meaning and acquisition of new knowledge and your classroom will become a more interactive and language-rich learning domain where children can increase their fluency, retrieval and application of knowledge.

3. Curriculum organisation and design

How can you ensure your curriculum is organised to allow cognitive challenge for more able pupils? You need to consider:

- What is planned for the students

- What is delivered to the students

- What the students experience

Schools with a high-quality curriculum for cognitive challenge use agreed teaching approaches and a whole-school model for teaching and learning. Teachers expertly and consistently utilise key features relating to learning preferences, knowledge acquisition and memory.

Planning a curriculum for more able pupils means providing a clear direction for their learning journey. It’s necessary to think beyond individual subjects, assessment systems, pedagogy and extracurricular opportunities, and to look more deeply at the ways in which these link together for the benefit of your pupils. If teachers can understand and deliver this curriculum using their subject knowledge and pedagogical skills, and if your school can successfully make learning visible to pupils, you’ll be able to move from well-practised routines to highly successful and challenging learning experiences.

Taking it further…

If we’re going to move beyond the traditional monologic and didactic models of teaching, we need to recast the role of teacher as a facilitator of learning within a supportive learning environment. For more able pupils this can be taken a step further. If you can build cognitive challenge into your curriculum and the way you manage learning, and support this with a language-rich classroom, the entire nature of teaching and learning can change. Your highly able pupils will become increasingly autonomous and more self-reliant. They’ll become masters of their learning as they gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter. You can then extend your role even further, from learning facilitator to “learner activator”.

This blog post is based on an article originally written for and published by Teach Primary magazine – read the full version here.

Additional reading and support:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

independent learning

metacognition

mindset

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

questioning

research

student voice

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By University of Oxford (Oxplore),

06 February 2020

|

The University of Oxford’s Oxplore website offers free resources to get students thinking about and debating a diverse range of “Big Questions”. Read on for three ways to get started with the platform, shared by Oxplore’s Sarah Wilkin…

Oxplore is a free, educational website from the University of Oxford. As the “Home of Big Questions”, it aims to engage 11- to 18-year-olds with debates and ideas that go beyond what is covered in the classroom. Big Questions tackle complex ideas across a wide range of subjects and draw on the latest research from Oxford.

Oxplore’s Big Questions reflect the kind of interdisciplinary and critical thinking students undertake at universities like Oxford. Each question is made up of a wide range of resources including: videos, articles, infographics, multiple-choice quizzes, podcasts, glossaries, and suggestions from Oxford faculty members and undergraduates.

Questioning can take many different forms in the classroom and is a skill valued in most subjects. Developing students’ questioning skills can empower them to:

- Critically engage with a topic by breaking it down into its component parts;

- Organise their thinking to achieve certain outcomes;

- Check that they are on track;

- Pursue knowledge that fascinates them.

Here are three ways Oxplore’s materials can be used to foster questioning and related skills…

1. Investigate what makes a question BIG

A useful starting point can be to get students thinking about what makes a question BIG. This can be done by displaying the Oxplore homepage and encouraging students to create their own definitions of a Big Question:

- Ask what unites these questions in the way we might approach them and the kinds of responses they would attract.

- Ask why questions such as “What do you prefer to spread on your toast: jam or marmite?” are not included.

- Share different types of questions like the range shown below and ask students to categorise them in different ways (e.g. calculable, personal opinion, experimental, low importance, etc.). This could be a quick-fire discussion or a more developed card-sort activity depending on what works best with your students.

2. Answer a Big Question

You could then set students the challenge of answering a Big Question in groups, adopting a research-inspired approach (see image below) whereby they consider:

- The different viewpoints people could have;

- How different subjects would offer different ideas;

- The sources and experts they could ask for help;

- The sub-questions that would follow;

- Their group’s opinion.

If you have access to computers, students could use the resources on the Oxplore website to inform their understanding of their assigned Big Question. Alternatively, download and print out a set of our prompt cards, offering facts, statistics, images and definitions taken from the Oxplore site:

Additional resources:

This activity usually encourages a lot of lively debate so you might want to give students the opportunity to report their ideas to the class. One reporter per group, speaking for one minute, can help focus the discussion.

3. Create your own Big Questions

We’ve found that no matter the age group, students love the opportunity to try thinking up their own Big Questions. The chance to be creative and reflect on what truly fascinates them has the appeal factor! Again, you might want to give students the chance to explore the Oxplore site first, to gain some inspiration. Additionally, you could provide word clouds and suggested question formats for those who might need the extra support:

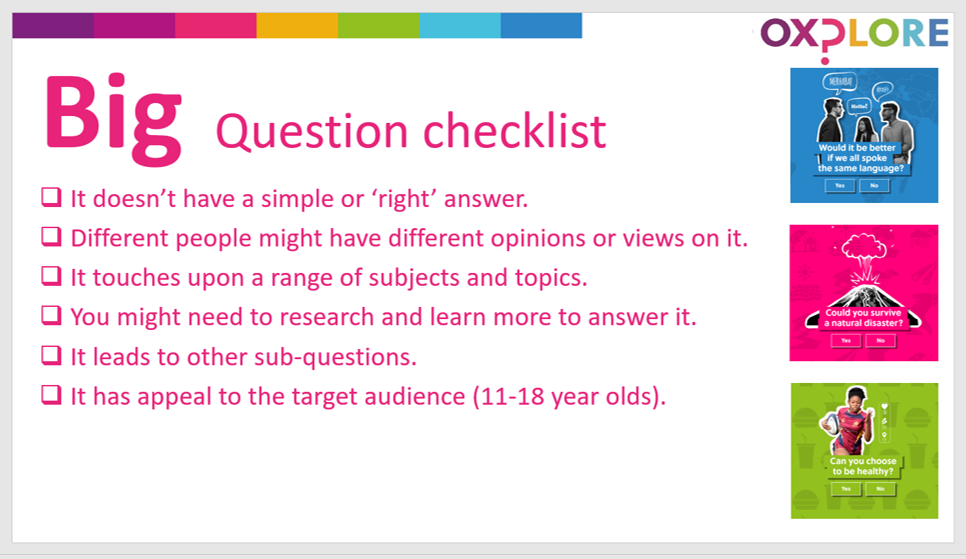

To encourage students to think carefully and evaluate the scope of their Big Question, you could present them with a checklist like the one below:

Extension activities could include:

- Students pitching their Big Question to small groups or the class (Why does it interest them? What subjects could it include? etc);

- This could feed into a class competition for the most thought-provoking Big Question;

- Students could conduct a mini research project into their Big Question, which they then compile as a homework report or present to the class at a later stage.

Take it further: join a Big Question debate

Each term the Oxplore team leads an Oxplore LIVE event. Teachers can tune in with their classes to watch a panel of Oxford academics debating one of the Big Questions. During the event, students have opportunities to send in their own questions for the panel to discuss, plus there are competitions, interactive activities and polls. Engaging with Oxplore LIVE gives students the chance to observe the kinds of thinking, knowledge and questions that academics draw upon when approaching complex topics, and they get to feel part of something beyond the classroom.

The next Oxplore LIVE event is on Thursday 13 February at 2.00-2:45pm and will focus on our latest Big Question: Is knowledge dangerous? If you and your students would like to take part, simply register here. You can also join the Oxplore mailing list to receive updates on new Big Questions and upcoming events.

Any questions? Contact the Oxplore team.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

enrichment

independent learning

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Hilary Lowe,

11 December 2019

Updated: 03 December 2019

|

NACE Education Adviser Hilary Lowe goes in search of the perfectly pitched challenge...

Building on NACE’s professional development and research activities, we continue to explore and refine the concept of ‘challenge’ in teaching and learning for high achievement – the central tenet of much of our work and the heart of provision for very able learners.

What do we mean by challenge?

The notion of challenge is multi-faceted and goes further than designing individual learning and assessment tasks. It merits a subheading which makes it clear what we mean. As a provisional and necessarily evolving definition:

“Challenge leads to deep and wide learning at an optimal level of understanding and capability. It encompasses appropriate learning activities but is more than that. Its other facets include, for example: the learning environment, the language of classroom interactions, and learning resources, together with the skills and attributes which the learner needs to engage with challenging learning encounters. These encounters may take place both within and beyond the classroom.”

Some of these building blocks coincide with pedagogical approaches and theoretical perspectives which enable challenging learning for a wide group of learners. It is important therefore that we also interrogate these perspectives and adapt related classroom practices to ensure relevance and application for the most able learners.

Our work on challenge in teaching and learning is part of a wider campaign that will also explore and promote the importance of a curriculum model which offers sufficient opportunity and challenge for more able learners.

Below, we focus on the design and delivery of challenging tasks and activities in the classroom which are likely to enable more able learners to achieve highly and to engage in healthy struggle.

Pitching it right: keep the challenge one step ahead

If teaching for challenge is providing difficult work that causes learners to think deeply and engage in healthy struggle, then when learners struggle just outside their comfort zone they will be likely to learn most. Low challenge with positive attitudes to learning and high-level skills and knowledge can generate boredom within a lesson, just as high challenge with poor learning attitudes and a low base of knowledge and skills can create anxiety. Getting the flow right, ensuring the level of challenge is constantly just beyond the learners’ level of skills and knowledge and their ability to engage will then create deeper learning and mastery.

By scaffolding work too much and for too long, and stealing the struggle from learners, we can undermine expectations and restrict the ranges of response that our learners could potentially develop unaided.

Implications for planning and teaching

What then are the implications for planning and for using every opportunity inside and outside the classroom to “raise the game”? Challenge should involve planned opportunities to move a learner to a higher level of achievement. This might therefore include planning for and finding opportunities in classroom interactions for:

- Tasks which encourage deeper and broader learning

- Use of higher-order and critical thinking processes

- Demanding concepts and content

- Abstract ideas

- Patterns, connections, synthesis

- Challenging texts

- Modelling and expecting precise technical and disciplinary language

- Taking account of faster rates of learning

- Questioning which promotes and elicits higher-order responses

When considering the level of challenge in your classroom, ask:

- Do you set high expectations which allow for the potential more able learners to show themselves?

- Have you reflected on prior learning and cognitive ability to inform your plans?

- Is your classroom organised to promote differentiation?

- Do you plan for a range of questions that will scaffold, support and challenge the full range of ability in your class?

- Can you recognise when learners are under- or over-challenged and adapt accordingly?

- Are you using examples of excellence to model?

- Will learners be challenged from the minute they enter?

Share with your learners your expert knowledge, your passion, your curiosity, your love of the subject and of learning. Have high expectations – and resist the urge to steal their struggle!

Challenge in the classroom: upcoming NACE CPD

New for 2020, NACE is running a series of one-day courses focusing on approaches to challenge and support more able learners in key curriculum areas. Led by subject experts, each course will explore research-informed approaches to create a learning environment of high challenge and aspiration, with practical strategies for challenge in each subject and key stage.

Details and booking:

An earlier version of this article was published in NACE Insight, the termly magazine for NACE members. Past editions are available here (login required).

Tags:

CPD

critical thinking

differentiation

feedback

mastery

myths and misconceptions

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Christabel Shepherd,

10 December 2019

Updated: 10 December 2019

|

Christabel Shepherd, Executive Headteacher of Bradford’s Copthorne and Holybrook Primary Schools, shares 10 tried-and-tested approaches to developing Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary.

"They just haven’t got the words!” This is something I have heard a number of times in my teaching career. As all teachers know, the consequence of children ‘not having the words’ means they are unlikely to be able to express themselves clearly. They may not be able to get the most from the experiences we offer. They are often judged by individuals beyond the school as lacking ability. They may display frustration and a lack of self-belief which, in turn, can lead to low levels of resilience and, in the case of many of the children I’ve taught, a tendency to be passive learners.

Above all, the vocabulary gap exacerbates social disadvantage. We have all seen the effects that result when children don’t have the words they need to truly express themselves, and to paint a true and vivid picture in the mind of a reader or listener. We also know that a focus on oracy and ‘closing the vocabulary gap’ opens the doors of opportunity for children and allows them to soar.

Challenge for all

At both the schools I lead, ‘challenge for all’ is a non-negotiable and at the heart of our ethos and vision. Both schools are members of NACE, and we believe that providing challenge for all our learners develops ability, raises aspirations, engenders resilience and is a key feature of a high-quality education.

Central to providing ‘challenge for all’ is a focus on high-quality language acquisition and use by pupils. How can we challenge learners effectively if there is a notable vocabulary gap, especially in terms of pupils’ knowledge, understanding and use of Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary? How can we embed higher order questioning and higher order thinking skills if the children can’t access the language?

Teaching Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary

I think most of us feel comfortable teaching Tier 3 vocabulary. It’s usually technical, often subject-specific, and we teach this in a very direct and focused way through a rich curriculum where key words and their meaning are explored and used in context.

Tier 2 vocabulary can be more difficult for children to grasp. It often expresses ‘shades of meaning’ which can be extremely subtle, and much of it relies on an experience and understanding of root words, prefixes and suffixes. As teachers, we are so used to experiencing these words or skilled at working out what they mean that we may assume they and their meaning are familiar to children too.

It is vital, therefore, if we want our children to engage effectively with the whole curriculum, articulate their thoughts, learning and aspirations, and access real challenge, that we have a whole-school focus on closing the vocabulary gap. We must directly teach and promote the understanding and use of Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary.

If you visit Copthorne Primary, where this approach is fully embedded, you will find wonderfully articulate young people. Our children are confident, active learners who relish a challenge and are not afraid to question adults, direct their own learning and express their views and opinions. Just being in their company for a few minutes makes my day.

Take a look at the Copthorne Pupil Parliament on YouTube (it’s just four minutes). Most of the children you’ll see arrived at the school with no English and are now able to think and speak fluently in at least two languages. Here’s how we do it…

1. Five-minute stories

Present children with three or four age/stage-appropriate Tier 2 words. The words must be those they have met before or have roots, prefixes or suffixes which they have experience of. Give them five minutes to write an engaging short story which must include the given words. This gives children the opportunity to use these words in their correct context, applying their developing knowledge of the shades of meaning, whilst developing long-term memory of the vocabulary. We adapted this idea from Chris Quigley who suggests using this strategy with words from year group spelling lists. Similarly, Tier 3 vocabulary can be developed by asking children to use a given selection of words in a summary about their learning in a particular subject.

2. Silent discussions

Get learners to discuss a topic through written communication only, using given Tier 2 or 3 vocabulary.

3. Model the language

When modelling writing, act out how to ‘think like a writer’, justifying and explaining your word choice, especially around synonyms from Tier 2. 4Talking school Provide opportunities and groupings for talk in every subject to ensure it absolutely pervades the whole curriculum. For example, try talk partners, debating, school council, drama or film-making. Use the ‘Big Questions’ resources at oxplore.org to promote debate and encourage the use of high-level vocabulary in context.

5. Language-rich environment

On every display, pose key questions using the appropriate technical vocabulary. This includes a ‘challenge’ question using Tier 2 vocabulary. Expect a response to the questions from the children. Display an appropriately aspirational (Tier 2) ‘word of the week’ in each classroom. After they’ve worked out its meaning, encourage the children to use it in their talk and writing and find its synonyms and antonyms.

6. Weekly vocabulary lessons

Take an object or theme and, using pictures, sound and film, support children in developing their high-quality descriptions using Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary, as well as more metaphorical language.

7. Reading across the curriculum

Maximise every opportunity in all subjects to teach reading skills and explore Tier 3 vocabulary in context. Use guided reading as an opportunity to really explore and pull apart those ‘shades of meaning’ for Tier 2 words in a range of text types. This allows for those rich conversations about specific word choice, meaning and effect.

8. Reciprocal reading

Introduce pupils to a whole-class text in small, manageable chunks. At the same time, thoroughly explore all new Tier 2 vocabulary. Encourage the children to use the words’ roots, context and any relevant existing knowledge to clarify meaning. Taking the time to explore misconceptions in reading and vocabulary use is a key feature of reciprocal reading and stops children from ‘glossing over’ words they don’t recognise.

9. Headteacher’s book club

Introduce extended guided reading groups for more able readers in Y5 and 6. Issue a challenging text to learners, along with an initial focus, and give pupils two to four weeks of independent reading time. Then meet together to share afternoon tea, discuss the book and explore new Tier 2 and 3 vocabulary. Encourage the children to use the new words in their writing and talk activities.

10. Year group writing events

Stage events such as an alien landing to stimulate pupils’ imagination and provide a specific context for the use of given Tier 2 and 3 words.

This article was originally published in Teach Reading & Writing magazine.

Christabel Shepherd is a NACE Associate and Trustee, and Executive Headteacher of Copthorne and Holybrook Primary Schools. She has extensive experience of leading on school-wide provision for more able learners, having used the NACE Challenge Framework to audit and develop provision in two schools, with both going on to achieve the NACE Challenge Award. Christabel regularly contributes to NACE's CPD programme, as well as delivering bespoke training and consultancy to help schools develop their provision for more able learners within an ethos of challenge for all.

Not yet a NACE member? Find out more, and join our mailing list for free updates and free sample resources.

Tags:

literacy

oracy

questioning

reading

student voice

vocabulary

writing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Sue Cowley,

11 November 2019

|

Alongside her webinar for NACE members, author and teacher trainer Sue Cowley shares five ways to ensure all learners are stretched and challenged – it’s differentiation, but not as you might expect!

It is tempting to think of differentiation as being about preparing different materials for different students – the classic ‘differentiation by task’. However, this type of differentiation is the most time-consuming for teachers in terms of planning. It can also be hard to create stretch through this approach, because it is difficult to pitch tasks at exactly the right level.

In reality, rather than being about preparing different activities, differentiation is a subtle skill that is not easily spotted ‘in action’. For instance, it might include adaptations to the teacher’s use of language, or ‘in the moment’ changes to a lesson, based on the teacher’s knowledge of individual learners.

1. Identify and account for prior knowledge

The highest-attaining students often have a great deal of knowledge about a diverse range of subjects – typically those areas of learning that fascinate them. They are likely to be autodidacts – reading widely around a favoured subject at home to find out more. Sometimes they will teach themselves new skills without any direct teacher input – for instance using YouTube to learn a language that is not on offer at school. At times, their level of knowledge or skill might outpace yours.

A key frustration for high attainers is the feeling that they are being taught things in school that they already know. Find ways to assess and ascertain the prior knowledge of your class before you start a new topic, and incorporate this information into your teaching. One simple strategy is to ask the class to write down the things they already know about a topic, before you begin to study it, and any questions that they want answered during your studies. Use these questions as a simple way to provide extension opportunities in lessons.

Where a learner has extensive prior knowledge of a topic, ask if they would like to present some of the knowledge they have to the class – this can help build confidence and presentational skills. It can also be useful for high-attaining learners to explain something they understand easily to a child who doesn’t ‘get it’ so quickly. The act of having to rephrase or reconceptualise something in order to teach it requires the learner to build empathy, understand alternative perspectives and think laterally.

2. Build on interests to extend

Where a high-attaining learner has an interest in a subject, they typically want to explore it far more widely than you have time to do at school. Encourage your high attainers to read widely around a subject outside of lesson time by providing them with information about suitable materials. A lovely way to do this is to give them suitable adult-/higher-level texts to read (especially some of your own books on a subject from home).

3. Inch wide, mile deep

When thinking about how to make an aspect of a subject more challenging, it is helpful to think about curriculum as being made up of both surface-level material and at the same time ideas that require much deeper levels of understanding. A useful metaphor is a chasm that must be crossed: those learners who struggle need you to build a bridge to help them to get over it. However, other students will be able to climb all the way down into the chasm to see what is at the bottom, before climbing up the other side.

For each area of a subject, consider what you can add to create depth. This might typically be about digging into an area more deeply, going laterally with a concept, or asking students to use more complex terminology to describe abstract ideas.

4. Use questioning techniques to boost thinking

The effective use of questions is vital for stretching your highest-attaining learners. Studies have shown that teachers tend to use far more closed questions than open ones, even though open-ended questions lead to more challenge because they require higher-order thinking.

Socratic questioning is a very useful way to increase the level of difficulty of your questions, because it asks learners to dig down into the thinking behind questions and to provide evidence for their answers. You can find out more about this technique at www.criticalthinking.org.

Another useful approach to questioning is a technique commonly used in early years settings, and known as ‘sustained shared thinking’ (for more on this, see this report on the Effective Pedagogy in the Early Years Project). In this approach, the child’s thinking is developed through the use of a ‘serve and return’ conversation in which open-ended questions are asked to build understanding.

5. Consider learner roles

Taking on a fresh role or perspective can really help to challenge our thinking. This is particularly so where we are asked to argue in favour of a viewpoint that we do not ourselves hold. This encourages the learner to build empathy with different viewpoints and to consider how a topic looks from alternative perspectives. A simple way to do this is by asking students to argue the opposite position to that which they actually hold, during a class debate.

Sue Cowley is an author, presenter and teacher educator. Her book The Ultimate Guide to Differentiation is published by Bloomsbury.

To find out more about these techniques for creating stretch and challenge, watch Sue Cowley's webinar on this topic (member login required).

Not yet a NACE member? Find out more, and join our mailing list for free updates and free sample resources.

Tags:

critical thinking

depth

differentiation

independent learning

progression

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Edmund Walsh,

08 October 2019

|

Ahead of his workshop on this topic, NACE Associate Ed Walsh shares seven key components of a challenging KS3 science curriculum…

“Is our KS3 course doing its job?” This is one of the most powerful questions a science leader in a secondary school can ask.

The new GCSE courses are no longer really new; many teachers are finding their way around the specifications, developing aspects such as the running order of topics, time allocated to activities and applying emphasis to areas that results analyses indicate are deficient.

There, is, of course, a limit as to what can be achieved within KS4. If students are starting on their GCSE courses with limitations in their grasp of science then the more effective solution may lie in KS3. I’d like to share some ideas as to how learners, especially the most able, can be effectively catered for at this stage. It is, of course, relatively easy to pose questions and harder work to identify answers. With this in mind I’ve also included some links to useful references and resources.

1. Talk the (science) talk

What language is being used in lessons? Are students being supported, challenged and expected to ‘talk science’? This needs to go beyond knowing the right names for objects, to also having a command of connectives. Would an observer in your classroom catch use of words and phrases such as ‘because’, ‘therefore’ and ‘as a result of’ – not just by the teacher but by students as they are developing explanations?

Read more: Useful materials on speaking and listening can be found in Session 4 of the National Strategies Literacy in Science Training Materials.

2. Ensure practical work adds value

What is the role of practical work in your science teaching and learning? Is it exploratory as well as illustrative? Does it prompt questions and ideas? Is it effective at developing the apparatus and techniques skills needed at GCSE so that able learners have, for example, mastered the use of microscopes by the time they start GCSE courses and can then concentrate on other aspects of investigations?

Read more: The newly published ASE/Gatsby report Good Practical Science provides benchmarks to support departments seeking to improve the effectiveness of practical science teaching.

3. Review your use of questioning and command words

What kind of questions are being asked? A good starting point is to look at the command words used in GCSE specifications and consider whether students are being exposed to these all the way through their secondary science experience. As well as ‘describe’ and ‘explain’, are able learners being asked to evaluate, compare, contrast and suggest? As well as closed and specific questions, are you posing open and exploratory questions?

Read more: Guidance on questioning is provided in unit 7 of Pedagogy and Practice: Teaching and Learning in Secondary Schools (DfES).

4. Develop writing (quality, not quantity)

What is the role of writing? This is not a plea for lengthy, exhaustive (and exhausting) experimental writeups or even necessarily for anything of any length. It’s more that there is a case for getting students producing short pieces of high-quality writing that do a particular job well. This might be, for example, comparing and contrasting different materials for a car body, suggesting and justifying an energy provision plan for a particular location or analysing a graph that shows how different carrier bags respond to loads.

Read more: Useful materials on writing can be found in Session 3 of the National Strategies Literacy in Science Training Materials.

5. Ensure key concepts are covered and revisited

Have the ‘cornerstone concepts’ been effectively introduced and revisited? Is the concept of energy well developed and do students understand what is meant by an ecosystem? Such key concepts can be seen as tools that scientists can reach for when developing explanations; able learners should become more proficient in doing this.

Read more: An overview of how key ideas can be planned for in KS3 is provided in AQA’s KS3 Science Syllabus.

6. Respond to learners’ needs

How responsive is the teaching to nurturing able learners and focusing on their learning needs? If these students are going to realise their potential at the end of GCSE then their KS3 experience needs to be tailored to areas in which they need a good grounding. For example, if they’re confident with the concept of a chemical reaction but less familiar with different types of reaction, can the latter be made a particular focus? Students who feel they are ‘treading water’ may not perform to the best of their ability.

Read more: A really good reference source on this is Dylan Wiliam’s Embedded Formative Assessment (2011, Solution Tree, 978-1-934009-30-7)

7. Develop science capital

Students are more likely to succeed if they see a purpose to their learning. Are there opportunities for them to see the doors that are open to young people who are competent and keen in STEM subjects? A good example of resources recently published to support this are the Royal Society’s series of videos with Professor Brian Cox – as well as demonstrating how experiments can be done in schools, they also show why these ideas are important and useful in society and highlight the cutting-edge research in each area.

Read more: This blog post from The Science Museum’s Beth Hawkins provides a useful introduction to the concept of science capital and how it can be developed. Plus, watch our webinar on this topic (member login required).

For additional support to develop your provision for more able learners in science, sign in as a NACE member to access Ed Walsh's NACE Essentials guide to realising the potential of more able learners in GCSE science, and recorded webinar on effective questioning in science.

Not yet a NACE member? Find out more, and join our mailing list for free updates and free sample resources.

Tags:

CPD

curriculum

free resources

GCSE

KS3

questioning

science

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By NACE,

17 April 2019

Updated: 03 June 2019

|

At our spring term meetup, hosted by Jesus College Oxford, NACE members from all phases and sectors joined to discuss and share approaches to developing independent learning skills. Read on for a selection of ideas to try out in your own school…

1. Extended research projects

Extended research projects are widely used across the NACE community, including Extended Project Qualifications (EPQs) as well as a range of other initiatives. At Birchensale Middle School, for example, Year 8 students undertake an independent research project in which points are collected by completing different tasks – the more challenging the task, the more points available. Learners have a choice of topics, presentation methods and supporting materials of different levels.

Meanwhile at Impington Village College, groups of more able learners in Years 8 to 10 from each faculty area meet fortnightly to support each other on an independent research project of their choice. With support from peers and their “faculty champion”, they develop higher-level research skills based on IB coursework models and the A-level EPQ.

2. Flipped learning

Alongside extended projects, members highlighted flipped learning as effective in developing independence. At Sarah Bonnell School (KS3-4) learners are provided with a bank of resources and reading for each topic, to work through independently ahead of lessons. Students’ response to this approach has been very positive, says the school’s Sabrina Sahebdin. “It allows them to come to the lesson prepared with questions and a chance to query areas where they need further clarification. Time is not wasted in fact finding during lessons; instead we apply knowledge, analyse and evaluate. It has stretched and challenged them further in aiding them with further research for peer teaching.”

3. Presenting to peers

Building on independent learning and research tasks, members highlighted the benefits of asking learners to present their findings to peers – digesting and sharing information in an accessible, engaging and/or persuasive way. Jamie Kisiel, Teaching and Learning Coordinator at Langley School (KS2-5), shared her use of a “knockout debate” competition, which she says has led to students providing more in-depth evaluation in essays and developing more thought-provoking questions, while also ensuring they have a strong foundation in the subject.

At Pangbourne College (KS3-5), learners are challenged to present as experts on a topic they have researched independently. G&T Coordinator Ellie Calver explains that while the whole class explores the same general topic, more able learners are tasked with presenting on the more open-ended and challenging aspects. She comments, “There is a sense of pride in being able to pull others forwards, a real interest in making the material interactive, and a drive to find out more in order to work out what is most significant.”

4. TIF tasks

At Caludon Castle School (KS3-5), each lesson and home-learning task includes a Take It Further or TIF activity – an opportunity to go deeper through independent learning. Assistant Headteacher Steff Hutchison explains, “The TIFs are usually fun, challenging, quirky, a little bit off the wall, so students want to engage with them.” Having come to expect and enjoy these tasks, more able learners now ask for additional TIFs or – even better – devise their own. Steff adds, “Doing the TIF is considered to be cool, so the majority of students of all abilities strive to complete at least one TIF in an average week.”

5. Student-run revision quizzes

At The Commonweal School (KS3-5), students take a leading role by running their own maths revision quizzes. Work in pairs or small groups, they develop questions on the topic being revisited, create a PowerPoint presentation and decide how points will be awarded. “The competitive element is a cause for great excitement – it’s good to see them having so much fun,” says G&T Coordinator Genny Williams. She adds that the initiative has helped learners develop a deeper understanding through working at the top of Bloom’s Taxonomy, given them a strong motivation to take learning further, and has contributed to improved attainment in termly tests.

6. Super-curricular activities

At Hydesville Tower School, learners in Years 3 to 6 are invited to join the Problem-Solving Club – offering opportunities to work with peers on practical and engaging problem-solving activities. Assistant Headteacher Manjit Chand says participants are more inclined to take risks and use metacognitive strategies, and have developed their self-confidence, independence and resilience.

Shrewsbury High School’s Super Curriculum features a range of opportunities for stretch and challenge, including an Art Scholars club and Sixth Form Feminist Society. Each brings together students and staff with a shared interest, providing opportunities to engage with external partners (such as Shrewsbury Museum and Art Gallery, which hosted an exhibition of students’ work) and to explore the subject from multiple perspectives – including relevant research and personal experiences. “Ultimately,” says the school’s Natalie Thomas, “these initiatives work as a result of inspiring a love of learning.”

Learners at Malvern St James (EYFS-KS5) also benefit from opportunities to think and discuss ideas beyond the curriculum, at “discussion suppers” – small-group events at which selected students and staff discuss a topic over supper. Participants are asked to research the theme of the evening beforehand and to come prepared to share their ideas, listen to others, challenge and be challenged in turn. Learning Support and Enrichment Coordinator Rebecca Jones comments, “Pupils admit that it is quite a daunting experience, but feel pleased that they have taken part afterwards.”

7. Building blocks for discussion

While food helps to fuel debate at Malvern St James, at Shipston High School structure is provided with the help of Duplo or Lego bricks. Working in small groups, learners take turns to contribute to the conversation, adding a brick to a shared construction each time they speak. The colour of brick determines the nature of their contribution – for example, red bricks to accept, yellow to build, blue to challenge. Jordan Whitworth, Head of Religion, Ethics and Philosophy and the school’s lead NACE coordinator, says this simple activity has helped learners develop a range of skills for critical and independent thinking.

8. Access to other students’ solutions

At King Edwin Primary School, pupils have opportunities to learn from peers not just within their own school, but across the country. Having participated in the NACE/NRICH ambassadors scheme, Assistant Headteacher Anthony Bandy shared his experience of using the low-threshold, high-ceiling maths resources provided by Cambridge University’s NRICH. In particular, he highlighted the impact of sharing the solutions published on the NRICH website – which allow learners to see how other students, from different phases and schools, have solved each problem. This can inspire more able learners to seek out different approaches, to grasp new strategies and skills independently – including those covered at later key stages – and to apply this learning in different contexts.

Find out more…

For additional ideas and guidance to help your more able students develop as independent learners, join our upcoming members’ webinar on this topic. The webinar will take place on 25 April 2019, led by Dr Matthew Williams, Access Fellow at Jesus College Oxford.

For full details and to reserve your place, log in to our members’ site.

Tags:

collaboration

enrichment

free resources

independent learning

problem-solving

project-based learning

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Charlotte Bourne, Globe Education,

12 April 2019

Updated: 03 June 2019

|

Charlotte Bourne, Deputy Head of Learning at Shakespeare’s Globe, shares four examples of free resources available via the Globe’s 2019 website on Romeo and Juliet, focusing on the development of Assessment Objective 2.

My last blog selected four resources from Shakespeare's Globe’s 2019 Romeo and Juliet website and explained how these could be used to address the needs of more able learners, within a context of challenge for all. Here, I want to drill down into one specific assessment objective within GCSE English literature and discuss four more resources that can support teaching and learning within this area. As ever, these resources are provided free of charge and form part of the Globe's commitment to increasing access to Shakespeare.

Studying a different play? Fear not… Through the Playing Shakespeare with Deutsche Bank project, Shakespeare's Globe also offers dedicated resource websites on:

You can also visit the Globe’s Teach Shakespeare website for hundreds of free resources, searchable by play, key stage and resource type.

AO2: analysing the creation of “meaning and effects”

Assessment Objective 2 (AO2) requires learners to “analyse the language, form and structure used by a writer to create meanings and effects, using relevant subject terminology where appropriate.”

Many of our resources begin with the “meaning and effects” that have been created. It is incredibly hard for learners to analyse a feature if it creates no effect on them, or if the meaning is obscure. Start with what interests them, or what stands out, then break it down to consider why and how this is the case.

This positions them as active learners and moves them beyond feature-spotting at word-level – important as better GCSE responses discuss the structure and dramatic impact of the text.

Furthermore, broadening learners’ understanding of ways in which meanings can be shaped – particularly in relation to Shakespeare and drama – will support their further study within the subject. Finally, this also supports learners to appreciate the text from the outside: as a conscious construct, a myriad of the writer’s choices, and the characters and plot as vehicles to carry the text’s meanings.

Read on for four free resources to help your learners develop in AO2…

The weekly blog by the Assistant Director takes learners behind the scenes of a theatre production. For AO2, this is helpful to reiterate the form, as the process – and fluidity – of interpretation of drama texts is brought to the fore: this is what we mean by “text in performance”.

The lesson activity accompanying week 1's blog looks at how Romeo changes his speech when speaking to Mercutio as opposed to speaking to Juliet, and what Shakespeare is therefore trying to suggest about his character. As well as familiarisation with different parts of the play, the comparative element draws on a higher-order thinking skill.

This activity is invaluable in foregrounding the form: as James Stredder notes, plays “are essentially speech utterances” (2009). It begins by grounding the real-world application of communication accommodation theory (see Howard Giles), applying this to Shakespeare's craft. The text-work starts with reading aloud to allow pupils to feel the different meanings and effects of each Romeo-construction (speech!). Learners then return to the blog to examine the “how” of these constructions, comparing the use of verse and prose.

This resource uses an interview with the actor playing Mercutio as a springboard for exploration. Linked to AO2, this is another way of emphasising the form and its impact on interpretation. The activity invites learners to examine textual evidence in order to decide to what extent they agree with the actor's interpretation. To add challenge, learners are asked to compare Mercutio's language with Romeo's on a particular theme: love. This pushes learners to unpick how each character's speech is used as a vehicle to convey different conceptions of love.

The next activity uses the actor's interpretation to analyse the impact Mercutio's character has on the dramatic structure: they compare Mercutio's timeline with the main events of the play, and consider to what extent Shakespeare uses Mercutio to drive the events that lead to the tragedy. AO3 is integrated with AO2 through the option to debate Mercutio's primary purpose as exploring the relationship between comedy and tragedy.

Both of these activities demand learners use references from different parts of the play and use a range of higher-order thinking skills to draw out the effect of Shakespeare's choices in constructing Mercutio.

One of the most complex, but also wonderfully rich, episodes in Romeo and Juliet is Mercutio's Queen Mab speech. The week 3 blog provides an insight into how the cast worked with this, and the accompanying lesson activity builds on this. It starts by asking learners to draw the images Mercutio creates at each stage of the speech (bar the last one), which helps in untangling the meaning. They then specify which words and phrases contributed to each section of their drawings, supporting with the precision of their analysis.

Learners then create freeze-frames of each image, reflecting on which words and phrases have had the greatest effect. The chronological sharing of these freeze-frames facilitates an interrogation of the structure: how does the speech change as it progresses? Learners then predict what the last image of the speech might be. After the revelation, read-aloud work furthers the focus on learners making choices about which words create the greatest effect here, only afterwards drilling down into language techniques. Learners finally consider how the messages within this speech could link to the wider themes of the play.

This resource is comprised of an article from the production programme on the language of love and hate in Romeo and Juliet, with accompanying lesson activities. The article deepens understanding of antithesis and oxymoron by exploring the relationship between them and providing examples from the play; however, perhaps most crucially, it models the relationship between the writer's message and how this is expressed in the language patterns of the play.

Patterns are key here: the lesson activities focus on speeches by Romeo and Juliet from different parts of the play to examine how Shakespeare uses the oxymoron to link the eponymous characters while simultaneously drawing important distinctions between them. Thus, learners are asked to analyse language and then consider how the structure impacts on the meaning of each instance.

To access these resources, plus a wealth of additional resources to support a challenging curriculum, visit 2019.playingshakespeare.org. Remember: the website tracks the production so please keep coming back to see what else we have added!

Tags:

English

free resources

GCSE

KS3

KS4

literacy

literature

questioning

reading

Shakespeare

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|