Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Elena Stevens,

28 March 2022

Updated: 24 March 2022

|

History lead and author Elena Stevens shares four approaches she’s found to be effective in diversifying the history curriculum – helping to enrich students’ knowledge, develop understanding and embed challenge.

Recent political and cultural events have highlighted the importance of presenting our students with the most diverse, representative history curriculum possible. The murder of George Floyd in May 2020 and the tearing down of Edward Colston’s statue the following month prompted discussion amongst teachers about the ways in which we might challenge received histories of empire, slavery and ‘race’; developments in the #MeToo movement – as well as instances of horrific violence towards women – have caused many to reflect on the problematic ways in which issues of gender are present within the curriculum. Diversification, decolonisation… these are important aims, the outcomes of which will enrich the learning experiences of all students, but how can we exploit the opportunities that they offer to challenge the most able?

At its heart, a more diverse, representative curriculum is much better placed to engage, inspire and include than one which is rooted in traditional topics and approaches. A 2018 report by the Royal Historical Society found that BAME student engagement was likely to be fostered through a broader and more ‘global’ approach to history teaching, whilst a 2014 study by Mohamud and Whitburn reported on the benefits of – in Mohamud and Whitburn’s case – shifting the focus to include the histories of Somali communities within their school. A history curriculum that reflects Black, Asian and ethnic minorities, as well as the experiences of women, the working classes and LGBT+ communities, is well-placed to capture the interest and imagination of young people in Britain today, addressing historical and cultural silences. There are other benefits, too: a more diverse offering can help not only to enrich students’ knowledge, but to develop their understanding of the historical discipline – thereby embedding a higher level of challenge within the history curriculum.

Below are four of the ways in which I have worked to diversify the history schemes of work that I have planned and taught at Key Stages 3, 4 and 5 – along with some of the benefits of adopting the approaches suggested.

1: Teach familiar topics through unfamiliar lenses

Traditionally, historical conflicts are taught through the prism of political or military history: students learn about the long-term, short-term and ‘trigger’ causes of the conflict; they examine key ‘turning points’; and they map the war’s impact on international power dynamics. However, using a social history approach to deliver a scheme of work about, for example, the English Civil War, complicates students’ understanding of the ‘domains’ of history, shifting the focus so that students come to appreciate the numerous ways in which conflict impacts on the lives of ‘ordinary’ people. The story of Elizabeth Alkin – the Civil War-era nurse and Parliamentary-supporting spy – can help to do this, exposing the shortfalls of traditional disciplinary approaches.

2: Complicate and collapse traditional notions of ‘power’

Exam specifications (and school curriculum plans) are peppered with influential monarchs, politicians and revolutionaries, but we need to help students engage with different kinds of ‘power’ – and, beyond this, to understand the value of exploring narratives about the supposedly powerless. There were, of course, plenty of powerful individuals at the Tudor court, but the stories of people like Amy Dudley – neglected wife of Robert Dudley, one of Elizabeth I’s ‘favourites’ – help pupils gain new insight into the period. Asking students to ‘imaginatively reconstruct’ these individuals’ lives had they not been subsumed by the wills of others is a productive exercise. Counterfactual history requires students to engage their creativity; it also helps them conceive of history in a less deterministic way, focusing less on what did happen, and more on what real people in the past hoped, feared and dreamed might happen (which is much more interesting).

3: Make room for heroes, anti-heroes and those in between

It is important to give the disenfranchised a voice, lingering on moments of potential genius or insight that were overlooked during the individuals’ own lifetimes. However, a balanced curriculum should also feature the stories of the less straightforwardly ‘heroic’. Nazi propagandist Gertrud Scholtz-Klink had some rather warped values, but her story is worth telling because it illuminates aspects of life in Nazi Germany that can sometimes be overlooked: Scholtz-Klink was enthralled by Hitler’s regime, and she was one of many ‘ordinary’ people who propagated Nazi ideals. Similarly, Mir Mast challenges traditional conceptions of the gallant imperial soldiers who fought on behalf of the Allies in the First World War, but his desertion to the German side can help to deepen students’ understanding of the global war and its far-reaching ramifications.

4: Underline the value of cultural history

Historians of gender, sexuality and culture have impacted significantly on academic history in recent years, and it is important that we reflect these developments in our curricula, broadening students’ history diet as much as possible. Framing enquiries around cultural history gives students new insight into the real, lived experiences of people in the past, as well as spotlighting events or time periods that might formerly have been overlooked. A focus, for example, on popular entertainment (through a study of the theatre, the music hall or the circus) helps students construct vivid ‘pictures’ of the past, as they develop their understanding of ‘ordinary’ people’s experiences, tastes and everyday concerns.

There is, I think, real potential in adopting a more diversified approach to curriculum planning as a vehicle for embedding challenge and stretching the most able students. When asking students to apply their new understanding of diverse histories, activities centred upon the second-order concept of significance help students to articulate the contributions (or potential contributions) that these individuals made. It can also be interesting to probe students further, posing more challenging, disciplinary-focused questions like ‘How can social/cultural history enrich our understanding of the past?’ and ‘What can stories of the powerless teach us about __?’. In this way, students are encouraged to view history as an active discipline, one which is constantly reinvigorated by new and exciting approaches to studying the past.

About the author

Elena Stevens is a secondary school teacher and the history lead in her department. Having completed her PhD in the same year that she qualified as a teacher, Elena loves drawing upon her doctoral research and continued love for the subject to shape new schemes of work and inspire students’ own passions for the past. Her new book 40 Ways to Diversify the History Curriculum: A practical handbook (Crown House Publishing) will be published in June 2022.

NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website; for details of this and all NACE member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

References

Further reading

- Counsell, C. (2021). ‘History’, in Cuthbert, A.S. and Standish, A., eds., What should schools teach? (London: UCL Press), pp. 154-173.

- Dennis, N. (2021). ‘The stories we tell ourselves: History teaching, powerful knowledge and the importance of context’, in Chapman, A., Knowing history in schools: Powerful knowledge and the powers of knowledge (London: UCL Press), pp. 216-233.

- Lockyer, B. and Tazzymant, T. (2016). ‘“Victims of history”: Challenging students’ perceptions of women in history.’ Teaching History, 165: 8-15.

More from the NACE blog

Tags:

critical thinking

curriculum

history

humanities

KS3

KS4

KS5

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Kirstin Mulholland,

15 February 2022

|

Dr Kirstin Mulholland, Content Specialist for Mathematics at the Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), shares a metacognitive strategy she’s found particularly helpful in supporting – and challenging – the thinking of higher-attaining pupils: “the debrief”.

Why is metacognition important?

Research tells us that metacognition and self-regulated learning have the potential to significantly benefit pupils’ academic outcomes. The updated EEF Teaching and Learning Toolkit has compiled well over 200 school-based studies that reveal a positive average impact of around seven months progress. But it also recognises that "it can be difficult to realise this impact in practice as such methods require pupils to take greater responsibility for their learning and develop their understanding of what is required to succeed” .

Approaches to metacognition are often designed to give pupils a repertoire of strategies to choose from, and the skills to select the most suitable strategy for a given learning task. For high prior attaining pupils, this offers constructive and creative opportunities to further develop their knowledge and skills.

How can we develop metacognition in the classroom?

In my own classroom, a metacognitive strategy which I’ve found particularly helpful in supporting – and, crucially, challenging – the thinking of higher-attaining pupils is “the debrief”. The debrief as an effective learning strategy links to Recommendation 1 of the EEF’s Metacognition and Self-regulated Learning Guidance Report (2018), which highlights the importance of encouraging pupils to plan, monitor and evaluate their learning.

In a debrief, the role of the teacher is to support pupils to engage in “structured reflection”, using questioning to prompt learners to articulate their thinking, and to explicitly identify and evaluate the approaches used. These questions support and encourage pupils to reflect on the success of the strategies they used, consider how these could be used more effectively, and to identify other scenarios in which these could be useful.

Why does this matter for higher-attaining pupils?

When working in my own primary classroom, I found that encouraging higher-attaining pupils to explicitly consider their learning strategies in this way provides an additional challenge. Initially, many of the pupils I’ve worked with have been reluctant to slow down to consider the strategies they’ve used or “how they know”. Some have been overly focused on speed or always “getting things right” as an indication of success in learning.

When I first introduced the debrief into my own classroom, common responses from higher-attaining pupils were “I just knew” or “It was in my head”. However, what I also experienced was that, for some of these pupils, because they were used to quickly grasping new concepts as they were introduced, they didn’t always develop the strategies they needed for when learning was more challenging. This meant that, when faced with a task where they didn’t “just know”, some children lacked resilience or the strategies they needed to break into a problem and identify the steps needed to work through this.

As I incorporated the debrief more and more frequently into my lessons, I saw a significant shift. Through my questioning, I prompted children to reflect on the rationale underpinning the strategies they used. They were also able to hear the explanations given by others, developing their understanding of the range of options available to them. This helped to broaden their repertoire of knowledge and skills about how to be an effective learner.

How does the debrief work in practice?

Many of the questions we can use during the debrief prompt learners to reflect on the “what” and the “why” of the strategies they employed during a given task. For example,

- What exactly did you do? Why?

- What worked well? Why?

- What was challenging? Why?

- Is there a better way to…?

- What changes would you make to…? Why?

However, I also love asking pupils much more open questions such as “What have you learned about yourself and your learning?” The responses of the learners I work with have often astounded me! They have encompassed not just their understanding of the specific learning objectives identified for a given lesson, but also demonstrating pupils’ ability to make links across subjects and to prior learning. This has led to wider reflections about their metacognition – strengths or weaknesses specific to them, the tasks they encountered, or the strategies they had used – or their ability to effectively collaborate with others.

For me, the debrief provides an opportunity for pupils’ learning to really take flight. This is where reflections about learning move beyond the boundaries and limitations of a single lesson, and instead empower learners to consider the implications of this for their future learning.

For our higher-attaining pupils, this means enabling them to take increasing ownership over their learning, including how to do this ever more effectively. This independence and control is a vital step in becoming resilient, motivated and autonomous learners, which sets them up for even greater success in the future.

References

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

language

maths

metacognition

pedagogy

problem-solving

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

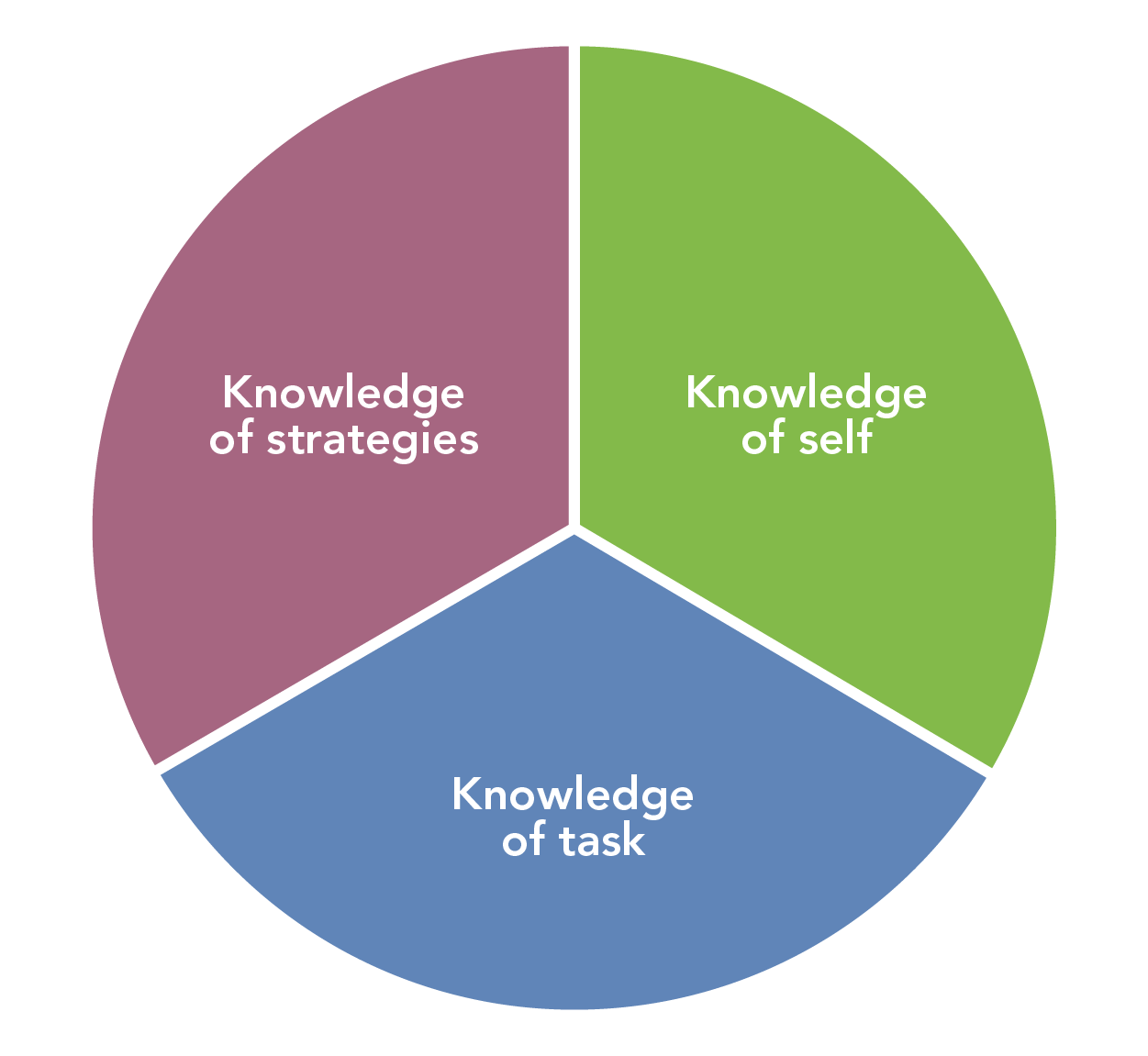

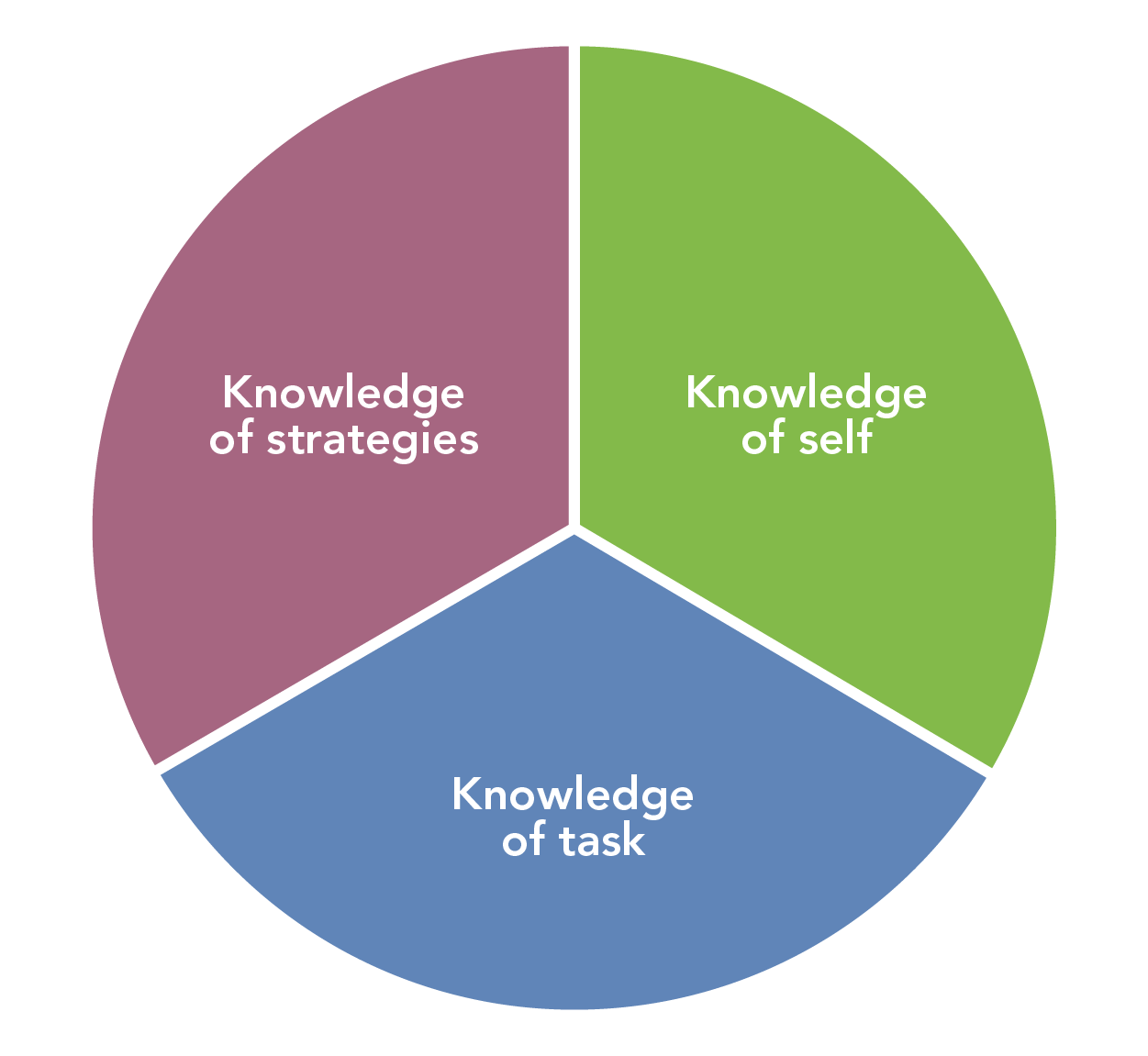

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ems Lord,

11 February 2022

|

Dr Ems Lord, Director of the University of Cambridge’s NRICH initiative, shares three activities to try in your classroom, to help learners improve their use of mathematical vocabulary.

Like many academic subjects, mathematics has developed its own language. Sometimes this can lead to humorous clashes when mathematicians meet the real world. After all, when we’re calculating the “mean”, we’re not usually referring to a measurement of perceived nastiness (unless it’s the person who devised the problem we’re trying to solve!).

Precision in our use of language within mathematics does matter, even among school-aged learners. In my experience, issues frequently arise in geometry sessions when working with pyramids and prisms, squares and rectangles, and cones and cylinders. You probably have your own examples too, both within geometry and the wider curriculum.

In this blog post, I’ll explore three tried-and-tested ways to improve the use of mathematical vocabulary in the classroom.

1. Introduce your class to Whisper Maths

“Prisms are for naughty people, and pyramids are for dead people.” Even though I’ve heard that playground “definition” of prisms and pyramids many times before, it never fails to make me smile. It’s clear that the meanings of both terms cause considerable confusion in KS2 and KS3 classrooms. Don’t forget, learners often encounter both prisms and pyramids at around the same time in their schooling, and the two words do look very similar.

One useful strategy I’ve found is using an approach I like to refer to as Whisper Maths; it’s an approach which allows individuals time to think about a problem before discussing it in pairs, and then with the wider group. For Whisper Maths sessions focusing on definitions, I tend to initially restrict learner access to resources, apart from a large sheet of shared paper on their desks; this allows them to sketch their ideas and their drawings can support their discussions with others.

This approach helps me to better understand their current thinking about “prismness” and “pyramidness” before moving on to address any misconceptions. Often, I’ve found that learners tend to base their arguments on their knowledge of square-based pyramids which they’ve encountered elsewhere in history lessons and on TV. A visit to a well-stocked 3D shapes cupboard will enable them to explore a wider range of examples of pyramids and support them to refine their initial definition.

I do enjoy it when they become more curious about pyramids, and begin to wonder how many sides a pyramid might have, because this conversation can then segue nicely into the wonderful world of cones!

2. Explore some family trees

Let’s move on to think about the “Is a square a rectangle?” debate. I’ve come across this question many times, and similarly worded ones too.

As someone who comes from a family which talks about “oblongs”, I only came across the “Is a square a rectangle?” debate when I became a teacher trainer. For me, using the term oblong meant that my understanding of what it means to be a square or an oblong was clear; at primary school I thought about oblongs as “stretched” squares. This early understanding made it fairly easy for me to see both squares and oblongs (or non-squares!) as both falling within the wider family of rectangles. Clearly this is not the case for everyone, so having a strategy to handle the confusion can be helpful.

Although getting out the 2D shape box can help here, I prefer to sketch the “family tree” of rectangles, squares and oblongs. As with all family trees, it can lead to some interesting questions when learners begin to populate it with other members of the family, such the relationship between rectangles and parallelograms.

3. Challenge the dictionary!

When my classes have arrived at a definition, it’s time to pull out the dictionaries and play “Class V dictionary”. To win points, class members need to match their key vocabulary to the wording in the dictionary. For the “squares and rectangles” debate, I might ask them to complete the sentence “A rectangle has...”. Suppose they write “four sides and four right angles”, we would remove any non-mathematical words, so it now reads “four sides, four right angles.” Then we compare their definition with the mathematics dictionary.

They win 10 points for each identical word or phrase, so “four right angles, four sides” would earn them 20 points. It’s great fun, and well worth trying out if you feel your classes might be using their mathematical language a little less imprecisely than you would like.

More free maths activities and resources from NRICH…

A collaborative initiative run by the Faculties of Mathematics and Education at the University of Cambridge, NRICH provides thousands of free online mathematics resources for ages 3 to 18, covering early years, primary, secondary and post-16 education – completely free and available to all.

The NRICH team regularly challenges learners to submit solutions to “live” problems, choosing a selection of submissions for publication. Get started with the current live problems for primary students, live problems for secondary students, and live problems for post-16 students.

Tags:

free resources

language

maths

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

problem-solving

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Jemma Sherwood,

11 February 2022

|

Based on a post originally published on Jemma Sherwood’s website, The World Is Maths.

Back in 2017 (where does time go?) I wrote this post on the importance of vocabulary, where I argued for including subject-specific (what we tend to refer to as ‘tier 3’) vocab more in our lessons.

Since then I’ve obviously thought more about this and, following on from conversations with David Didau, I wanted to get down another observation.

In my experience, maths teachers can have a tendency to underestimate two things:

- The vocabulary our pupils can cope with.

- The effect of bypassing the correct vocab.

Let me elaborate.

The vocabulary our pupils can cope with

Our pupils are capable of learning lots of words. They learnt to speak as youngsters and acquired thousands of them, but we know that many of them don’t move past the basic or intermediate literacy skills to those they need to access more advanced material (Shanahan and Shanahan, 2008). Something happens to many students at secondary age whereby their language acquisition falters. If that is the case, then it falls to us to accept that we’re not teaching them this as well as we could. We must maintain the highest of expectations of all our pupils and part of that is building language acquisition into our lessons such that it is both integral and normal.

What do integral and normal look like? Integral means you value language acquisition as an essential part of your teaching, that you understand its necessity in an education. You seize every opportunity to teach new words, you make pupils practice them – saying them out loud, using them in sentences in context – and you carefully build this into what you do. Normal means language acquisition teaching isn’t an add-on and it’s not over-complicated. We don’t need fancy worksheets and analysis of etymology (although etymology is fascinating and all students should meet it). If we make the teaching of language (or anything, for that matter) too onerous or time-consuming it won’t happen properly. It must be a simple, everyday occurrence, as normal as anything else we do.

When the teaching of language is integral and normal you see that pupils are able to learn really rather complex and specific vocabulary very well and this, in turn, allows them to think more precisely and to communicate more clearly.

Returning to the paper referenced earlier, the authors spent some time talking to mathematicians, scientists and historians to determine what reading looked like in each discipline. There were specific elements of reading that were valued to a different extent by each. The mathematicians valued close reading and re-reading, specifically because reading in mathematics is linked to precision, accuracy and proof. I particularly like this quote:

Students often attempt to read mathematics texts for the gist or general idea, but this kind of text cannot be appropriately understood without close reading. Math reading requires a precision of meaning and each word must be understood specifically in service to that particular meaning.

If we want to take our students on a pathway to being mathematical, thinking like a mathematician, we should build in language acquisition and precision reading as a principle of this.

The effect of bypassing the correct vocab

Something I see very regularly in classrooms is teachers avoiding using correct vocab, I think (from conversations I’ve had) because they are worried that particular vocab will make it harder to understand a concept. This is best explained with an example:

Teacher: A factor is a number that goes into another number.

How many times have you said this? I know I have! I think it happens because of a perception that a “simplified” definition makes this word accessible to more pupils. However, I would argue that we are making the word specifically less accessible in doing this.

What does ‘goes into’ really mean? As a novice without a strong mathematical background I could interpret this in a number of ways. However, if my teacher tells me, “A factor is a number that divides another number with no remainder”, or similar, and accompanies this with examples and non-examples, I can make more sense of the word from the start. Moreover, if my teacher regularly refers to the word ‘factor’ alongside this definition, and asks my peers and me this definition, and gets us hearing it and rehearsing it, then I start to associate the word ‘division’ with ‘factor’ and I am less likely to confuse it with ‘multiple’. Eventually, it will become part of my fluent vocabulary.

In ‘dumbing down’ a definition, we work against understanding rather than for it. That doesn’t mean we have to go all-out Wolfram Mathworld* on our pupils, but it does mean we have to consider the implications of our own use of language and how we can make small changes that have a positive impact. It’s worth taking some time with your team to discuss where else we have a tendency to bypass proper vocabulary or definitions, and think about the specific negative effects this will have on our pupils. How can you, as a team, work towards increasing your pupils’ language acquisition and precision? What ideas or concepts do you want them to automatically associate a certain word with? Design your instruction towards that aim.

*“A factor is a portion of a quantity, usually an integer or polynomial that, when multiplied by other factors, gives the entire quantity.” Mathworld

Jemma Sherwood is a Senior Lead Practitioner for Maths, and the author of How to Enhance Your Maths Subject Knowledge: Number and Algebra for Secondary Teachers. Find out more about Jemma on her website, or follow her on Twitter.

Tags:

language

maths

oracy

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By NACE team,

10 February 2022

|

Hodder Education’s Review magazines provide subject-specific expertise aimed at GCSE and A-level students, featuring the latest research, thought-provoking articles, exam-style questions and discussion points to deepen learners’ subject knowledge and develop independent learning skills.

Earlier this academic year, we partnered with Hodder on a live webinar for NACE members, followed by an opportunity to undertake a free trial subscription to the Review magazines, and then reconvening for an online focus group to share experiences, ideas and feedback.

Below are 15 ways NACE members suggested this resource could be used:

- Wider reading – encouraging learners to read more widely in their subjects, developing deeper and broader subject knowledge

- Flipped learning – tasking students with reading an article (or articles) on a topic ahead of a lesson, so they are prepared to discuss during class time (members noted that this approach benefits from practising reading comprehension during lesson time first)

- Developing cultural capital – exposure to content, contexts, vocabulary, and text formats which learners might not otherwise encounter

- Independent research and project work – to support independent research and projects such as EPQs, for example by using the digital archives to search on a particular theme

- Developing literacy and vocabulary – exposure to subject-specific and advanced vocabulary; this was highlighted by some schools as a particular concern post-pandemic

- Shared text during lessons – used to support lessons on a particular topic, and/or to develop comprehension skills

- Developing exam skills – using the magazines’ links to specific exam skills/modules, and practice exam questions at the end of articles

- Examples of academic/exam skills in practice – providing examples of how a text or topic could be approached and analysed, and ways of structuring an essay/response

- Library resource – signposted to students and teachers by school librarian to ensure a diverse, challenging reading menu is available to all

- Linking learning to real-world contexts – providing examples of how curriculum content is being applied in current contexts around the world, helping to bring learning to life

- Broadening career horizons – examples of different careers in each subject area, giving learners exposure to a range of potential future pathways

- Extracurricular provision – used as a resource to support subject-specific clubs, or general research/debate clubs

- Developing critical thinking and oracy skills – to support strategies such as the Harkness method, as part of a wider focus on developing critical thinking and oracy skills

- Exposure to academic research – preparing students for further education and career opportunities

- Fresh perspectives on curriculum content – new angles and insights on well-established modules and topics – for teachers, as well as students!

Find out more:

Discount offer for NACE members

NACE members can benefit from a 25% discount on Hodder's digital and print resources, including the Review magazines (excluding student £15 subscriptions). To access this, and our full range of member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

Does your school use the Review magazines or a similar resource? To share your experience and ideas, contact communications@nace.co.uk

Tags:

aspirations

enrichment

independent learning

KS4

KS5

literacy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

08 November 2021

|

The opportunities that present themselves to teachers these days are truly amazing. Last summer the chance to write and deliver a Zoom-based programme of learning to primary-aged pupils in Beijing was presented to me. Yes, Beijing. How could I refuse the opportunity to apply an English teaching style to another culture? Through a partnership between NACE and a private educational provider I embarked upon a programme of 16 two-hour sessions over a period of eight weeks via Zoom, using Google Classroom for resources and homework. The lessons were taught from 7-9pm 9pm Beijing time. Would my teaching keep the nine-year olds awake on a Sunday night?

The context

The education company I worked with offers what it terms ‘gifted and talented programmes’ to all ages and across the curriculum. The pupils mainly attended international schools and had their school lessons taught in English. The programmes have previously been delivered in person during the summer holidays by overseas teachers, primarily from the US. A move to Zoom-based learning after the pandemic has proved successful and now lessons are offered throughout the year in the evening and at the weekend with parents paying highly for the courses. The company organised the programme very well with training and support for the teacher at every stage. It is an impressive operation.

I taught an English literature unit based upon a comparative novel study using ‘The Iron Man’ and ‘The Giant’s Necklace’ – texts familiar to many Key Stage 2 teachers. The pupils worked hard in lessons, listened well and thought deeply. They retained knowledge well and I used retrieval practice at the start of most lessons. They completed these tasks eagerly. They were a pleasure to teach. Off-task behaviour was rare, pupils laughed when jokes were made – though of course humour was lost in translation at times (or maybe my jokes were not funny).

What worked?

Central to the learning was the pupils reading aloud. They loved this. It gave me the chance to clarify meaning, check vocabulary and asks questions at depth. All pupils read, some with impressive fluency given it was their second language. Parents commented they were not used to working this way. I think in other courses they often read for homework and then in lessons answered questions at length and then wrote essays. Despite being young there is an emphasis on academic writing. One pupil referred to his story as an essay, revealing that writing a story was unusual for his studies. Writing the story was a highlight for the pupils, one I suspect they are not used to. The reading also allowed for targeted questions, which the parents seemed to like, having not seen the technique used before. Yes, parents often sat next to their child, out of my eyesight, to help if needed. Hearing them whisper what to say on occasion was a new one for me.

To get an idea of the dedication of the pupils and support of the parents, it is worth mentioning that one pupil joined the lesson while travelling home on a train from her holiday. With her mum sat next to her, she joined in the lesson as best she could and all with a smile on her face. Another pupil said her father had asked her how she was reviewing the learning from the previous lesson each week. Learning is valued. Technical difficulties were rare but when they arose the pupils were proactive in overcoming difficulties, moving rooms and logging on with another device. Resilience and self-regulation was noticeably high. The last lesson included a five-minute presentation from each pupil on what they had learned from the unit. Pupils prepared well, the standard was high and pupils showed depth of understanding of the themes covered.

Addressing the language gap

As a teacher the main challenge to emerge was the gap between the pupils’ understanding of complex literary concepts and the use of basic English. The units are aimed at what is termed ‘gifted and talented’ yet at times I needed to cover areas such as verb tenses at a basic level. In English assessment terms the students were at times working at Year 6 greater depth for reading and some aspects of their writing, but were only ‘working towards’ in other areas.

I have decades of experience teaching EAL learners, the majority of whom attained at or above national expectation at the end of Key Stage 2 despite early language challenges. Here the gap was even more pronounced. Should I focus on the higher-order thinking and ignore what was essentially a language issue? I decided not to do that since the students need to develop all aspects of their English to better express their ideas, including writing. I did mini-grammar lessons in context, worked primarily on verb tenses in their writing and when speaking, and prioritised Tier 2 vocabulary since Tier 3 specialist vocabulary was often strong. They knew what onomatopoeia was, but not what a plough was, let alone cultural references like a pasty. Why would they?

Motivations and barriers

At the start of each lesson, I welcomed each pupil personally and asked them, ‘What have you been doing today?’ Almost every answer referred to learning or classes. They had either completed other online lessons, swimming lessons, fencing lessons, piano practice (often two hours plus) or other planned activities. Rarely did a pupil say something like ‘I rode my bike’. Having a growth mindset was evident and the students understood this and displayed admirable resilience. Metacognition and self-regulation were also evident in learning.

However, one area where the pupil did struggle was in self-assessment. The US system is based on awarding marks and grades regularly, including for homework. I chose not to do this, thinking grades for homework would be somewhat arbitrarily awarded unless something like a 10-question model was used weekly. The research on feedback without grades suggests that it leads to greater pupil progress and this was my focus. It would be interesting to explore with the students whether my lack of grade awarding lowered their motivation because they were used to extrinsic rather than intrinsic motivation. Does this contradict my assertion that growth mindset was strong?

Another issue emerged linked to this – that of perfectionism. One pupil was keen to show her knowledge in lessons but was the only pupil who rarely submitted homework. A large part of the programme was to write a story based on ‘The Iron Man’, which this student did not seem to engage with. At the parents’ meeting the mother asked if she could write for her child if it was dictated, a suggestion I rejected saying the pupil needed to write so that I could provide feedback to improve. It became clear the child did not want to submit her work because it was ‘not as good as their reading’. The child had told me in the first lesson that they had been accelerated by a year at school. I fear problems are being stored up that my gentle challenges have only now begun to confront and that may take a long time to resolve. This was not the case for the other pupils, but the idea of pressure to work hard and succeed was always evident. I realise the word ‘pressure’ here is mine and may not be used by others in the same context, including the parents.

Parental support

So, what of parental engagement? The first session began with getting-to-know-each-other activities and a discussion on reading. After 20 minutes the TA messaged me to say the parent of one pupil felt the lesson was ‘too easy’. Nothing like live feedback! I messaged back that the aim at that point was to relax the children and build a teaching relationship. A few weeks later the same parent asked to speak to me at the end of the lesson. I was prepared for a challenge that did not materialise. She said her child liked the lessons and she loved the way I asked personalised questions to extend her child. She was not used to her being taught this way. I used a mixture of cold-calling, named lolly-sticks in a pot and targeted questions, which seemed novel and the children loved.

Parent meetings were held half-way through the unit and feedback about things like the questioning wasvery positive. The extremely upbeat response was surprising since the teaching seemed a little ‘flat’ to me given the limitations of Zoom but that is not how it was received. The pupils seemed to enjoy the variety of pace, the high level of personal attention, the range of tasks, the chunking of the learning and the sense of fun I tried to create. Parents asked when I was delivering a new course and wanted to know when I was teaching again.

Final reflections

So, what did I learn? Children are children the world over, which we all know deep down. But these children apply themselves totally to their work. They expect to work hard and enjoy ‘knowing’ things. Their days are filled with activity and learning. Zoom can work well but still the much-prized verbal feedback is not the same from 5,000 miles away.

And finally, as a teacher I have learned over the years to be professional and to keep teaching whatever happens. When a pupil said they didn’t finish their homework because they were traveling back home, I enquired where they had been. ‘Wuhan’ they replied. Without missing a beat, I further asked, ‘So what do you think about the plot in chapter two then?’

Would you be interested in sharing your experiences of teaching remotely and/or across cultures? Is this an area you’d like to explore or develop? Contact communications@nace.co.uk to share your experience or cpd@nace.co.uk to express your interest in being part of future projects like this.

Tags:

feedback

language

literature

lockdown

mindset

motivation

parents and carers

pedagogy

perfectionism

questioning

remote learning

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Hilary Lowe,

08 November 2021

|

NACE Research and Development Director Hilary Lowe explores the relationship between language and learning, and the development of language-rich learning environments as a key factor in cognitively challenging learning experiences.

“We use language to define our world, while at the same time the social world in which we live defines our language. The structure of language and the variation we find within it depend both on the social world as well as the ways in which we create an identity for ourselves and the ways in which we build relations with others. Understanding how language both constrains our thoughts and actions and how we use language to overcome those constraints are important lessons for all educators.” (Silver & Lewin, 2013)

We are sometimes so busy talking in classrooms that we forget about the centrality of language for learning. It is for this reason that this blog post focuses on what is arguably a neglected area in the training of teachers: an understanding of the primacy of language in the learning process, of the link between language and higher-level cognition and high achievement, and the critical role of teachers in developing high-level language skills at all stages of schooling.

The development of language and literacy has long been a tenet of the National Curriculum as well as a significant area of research. Research such as that from Oxford Children’s Language (Oxford, 2018; 2020) has continued to emphasise the importance of linguistic wealth, and the link between paucity of language and academic failure and diminished life chances.

The notion of ‘oracy’ has been less visible in policy developments but has received more recent attention through, for example, the survey undertaken by the Centre for Education and Youth and Oxford University (2021) and the Oracy APPG Speak for Change Inquiry report (April, 2021). The APPG inquiry found that the development of spoken language skills requires purposeful and intentional teaching and learning throughout children’s schooling. It also found that there is a concerning variation in the time and attention afforded to oracy across schools, meaning that for many children the opportunity to develop these skills is left to chance. The inquiry concluded that there is an indisputable case for oracy as an integral aspect of education. The conclusions also emphasised the primordial place of oracy for young people and the critical role of employers, teachers and Ofsted in trying to ensure that these skills are developed to a high level.

In the first phase of NACE’s research initiative Making Space for Able Learners, which focuses on cognitive challenging learning, we were delighted to find examples of effective practices in language development and use, which led us to a renewed interest in the significance of language and discourse in high achievement. The schools in the project which demonstrated consistently excellent practice and high achievement for their most able learners had a systematic and systemic approach to the development and use of high-level language skills alongside wider literacy and oracy development (see below for examples). Some background: language, thinking and learning

The interaction between thought and language has long been the subject of research and academic debate. The thesis that natural language is involved in human thinking is universally well supported, although research into language and cognition often makes reference to ‘strong and weak theories’ of this thesis. Research suggests that higher-level language processes hold a pivotal role in higher-order executive and cognitive activities such as inference and comprehension, and indeed wider expressive communication skills.

Vygotsky (1978) writes that "[…] children solve practical tasks with the help of their speech, as well as their eyes and hands" (p. 26). In Vygotsky's view, speech is an extension of intelligence and thought, a way to interact with one's environment beyond physical limitations: “[…] the most significant moment in the course of intellectual development, which gives birth to the purely human forms of practical and abstract intelligence, occurs when speech and practical activity, two previously completely independent lines of development, converge.” (p. 24).

This higher level of development enables children to transcend the immediate, to test abstract actions before they are employed. This permits them to consider the consequences of actions before performing them. But most of all, language serves as a means of social interaction between people, allowing "the basis of a new and superior form of activity in children, distinguishing them from animals" (p. 28f). Vygotsky wrote, "human learning presupposes a specific social nature and a process by which children grow into the intellectual life of those around them" (p. 88). Language acts both as a vehicle for educational development and as an indispensable tool for understanding and knowledge acquisition.

In the classroom, therefore, we need to attend to the development of higher-level language processes as explicitly as we do to substantive subject skills and knowledge.

The functions of language in education

The various functions of language most pertinent in the classroom include:

- Expression: ability to formulate ideas orally and in writing in a meaningful and grammatically correct manner.

- Comprehension: ability to understand the meaning of words and ideas.

- Vocabulary: lexical knowledge.

- Naming: ability to name objects, people or events.

- Fluency: ability to produce fast and effective linguistic content.

- Discrimination: ability to recognize, distinguish and interpret language-related content.

- Repetition: ability to produce the same sounds one hears.

- Writing: ability to transform ideas into symbols, characters and images.

- Reading: ability to interpret symbols, characters and images and transform them into speech.

(Lecours, 1998).

All of these functions are key components in the teaching and learning process. Teachers and students use spoken and written language to communicate with each other formally and informally. Students use language to comprehend, to question and interrogate, to present tasks and learning acquired – to display knowledge and skills. Teachers use language to explain, illustrate and model, to assess and evaluate learning. Both use language to develop relationships, knowledge of others and of self. But language is not just a medium for communication – it is intricately bound up with the nature of knowledge and thought itself.

What does this mean for cognitively challenging learning?

For the development of high levels of cognition and to achieve highly, pupils need to develop the language associated with higher-order thinking skills in all areas of the curriculum, such as hypothesising, evaluating, inferring, generalising, predicting or classifying (Gibbons, 1991).

In an educational context it is through iterations of linguistic interactions between teacher and student – and peer to peer – that the process of advancing in learning and knowledge occurs. As Hodge (1993) notes, with limited time in the classroom, teachers often spend much of the available time conveying information rather than ensuring comprehension. This reduces the opportunities for a range of linguistic interactions and for learners to acquire and practise the higher-level language skills associated with high achievement. Planning and organising teaching and learning therefore needs to allow for an increase in opportunities for rich language environments and interactions alongside a cognitively challenging curriculum.

In the NACE research project school visits, we witnessed numerous incidences of highly effective and consistent practices in classroom discourse which clearly contributed to the achievement of highly able learners. These included:

- Teachers modelling advanced language and skilled explanation and questioning;

- Pupils being taught the language of skills such as reasoning, synthesis, evaluation;

- Frequent use of ‘dialogic’ frameworks and enquiry-based learning;

- The use of disciplinary discourse and higher tiers of language;

- Instructional models which include and prioritise the above.

Examples of effective, language-rich learning environments from the project include:

- Portswood Primary School: focus on the early development of vocabulary, language and talk. Teachers use sophisticated language to communicate expectations and learning.

- Alfreton Nursery School: teaching develops skills of concentration, as pupils focus on a central stimulus/object and formulate “big questions”. There is also an explicit focus on team working with reference to reasons “why we can agree to disagree” and the importance of listening. The teacher follows these pupil-led ideas in later sessions.

- Glyncoed Primary School: a challenging curriculum is achieved through planning and delivery of problem solving-based activities, extended and cognitively demanding tasks, and pupil choice. Teacher talk and high-level and qualitatively differentiated questioning, rich dialogue and cognitive talk is in evidence. Excellent modelling and explanations are also pervasive.

- Greenbank High School: pupils are stimulated by differentiated questions prompting them to test hypotheses, make predictions and transfer their knowledge to new contexts. As a result, pupils are working at a strong, sustained pace.

You can read more about the project and order copies of the report here.

Improving the quality and nature of linguistic interaction and discourse within the classroom can better equip learners to engage in cognitive challenge. Learners thus equipped can also move more effectively from guided practice to independence and self-regulation. Teachers working with more able pupils must have a clear pedagogical strategy in mind, with discourse and well-planned questioning an integral part of that strategy. By using a highly interactive pedagogical model, which is language-dependent, teachers get rapid feedback about how well knowledge schemas are forming and how fluent pupils have become in retrieving and using what they have learnt. Working with the most able learners, the quality of questioning and questioning routines must provide the teacher with diagnostic information and the pupils with increased challenge.

Creating language-rich schools and classrooms: implications for teacher development

The development of language is too important to be left to be ‘caught’ alongside the rest of the taught curriculum. We need to give it explicit attention across the curriculum, alongside subject knowledge and skills. To do this expertly teachers should have access to professional development opportunities which give them insights into substantive areas of language acquisition and development – including what that means at different ages and stages and for learners of different abilities and language experience.

NACE’s future CPD and resources will therefore focus on issues in and strategies for language development for high achievement, including:

- Case studies of NACE evidence schools with excellent practice in language for high achievement;

- The language needs and characteristics of different learners, including the most able;

- Creating language-rich school environments;

- Approaches to teaching and learning for language development;

- EAL learners;

- Developing a whole-school language policy.

Schools accredited with the NACE Challenge Award are invited to join our free termly Challenge Award Schools Network Group events (online) to share effective practice in this and other areas. View upcoming events here, or contact communications@nace.co.uk to learn more about NACE’s work in this field and/or to share your school’s experience.

References

- Oracy All-Party Parliamentary Group, Speak for Change, oracy.inparliament.uk, 2021

- Centre for Education and Youth with Oxford University Press, Oracy after the Pandemic, cfey.org, 2021

- Gibbons, P., Learning to Learn in a Second Language, Primary English Teaching Association, 1991

- Hillman, D. C. A., https://www.quahog.org/thesis/role.html, 1997

- Hodge, B., Teaching as Communication, Routledge, 1993

- Hodge, G. I. V. and Kress, G. R., Language as Ideology, Routledge, 1999

- Lecours, A. R. et al, Literacy and The Brain in The Alphabet and The Brain, Springer-Verlag, 1988

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A., Making Space for Able Learners, NACE, 2020

- Oxford Language Report, Why Closing the Language Gap Matters, OUP, 2018

- Oxford Language Report, Bridging the Word Gap at Transition, OUP, 2020

- Silver, R. E. and Lewin, S. M., Language in Education: Social Implications, Bloomsbury, 2013

- Vygotsky, L. S., Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes, London: Harvard University Press, 1978

Tags:

cognitive challenge

CPD

language

oracy

research

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 October 2021

|

NACE Research & Development Director Dr Ann McCarthy shares key principles for effective assessment planning and practice, within cognitively challenging learning environments.

Following two academic years of uncertainty and alternative arrangements for teaching and assessment, the conversation regarding testing and assessment has become increasingly important. Upon return to the routines of day-to-day classroom teaching, schools have had to find ways to assess knowledge, progress and understanding achieved through distance learning or redesigned classroom practices. For older pupils there has been a need to provide evidence to examination boards to secure grades and guarantee appropriate progression routes. This inherent need to provide checks and balances before pupils’ achievement is recognised can become a distraction from the art of teaching. In fact, Rimfield et al (2019) found a very high agreement between teacher assessments and exam grades in English, maths, and science.

- Could we examine less often and use classroom-based assessment more often?

- Should we rethink testing and assessment and their position in the learning process?

Testing vs assessment

The terms test and assessment are often used interchangeably, but in the context of education we need to recognise the difference. A test is a product which is not open to interpretation; it uses learning objectives and measures success achieved against these. Teachers use tests to measure what someone knows or has learned. These may be high-stakes or low-stakes events. High-stakes tests may lead to a qualification, grading or grouping, whereas low-stakes tests can support cognition and learning. Testing takes time away from the process of learning and as such testing should be used sparingly, when necessary and when it contributes significantly to the next steps in teaching or learning.

Assessment, by contrast, is a systematic procedure which draws on a range of activities or evidence sources which can then be interpreted. Regardless of the position teachers hold regarding the use of testing and examinations, meaningful assessment remains an essential part of teaching and learning. Assessment sits within curriculum and pedagogy, beginning with diagnostic assessment to plan learning which best reflects the needs of the learner. A range of formative assessment activities enable the teacher and pupils to understand progress, improve learning and adapt the learning to reflect current needs. Endpoint activities can be used as summative assessments to appreciate the degree to which knowledge has been acquired, alongside varied and complex ways in which that knowledge can be used.

Assessment might be viewed in three different ways: assessment of learning; assessment for learning; and assessment as learning. The choice of assessment practice will then impact on its use and purpose. Regardless of the process chosen and the procedures used, the teacher must remember that the value of the assessment is in the impact it has on pedagogy and practice and the resulting success for the pupils, rather than as an evidence base for the organisation.

NACE research has shown that cognitively challenging experiences – approaches to curriculum and pedagogy that optimise the engagement, learning and achievement of very able young people – will have a significant and positive impact on learning and development. But how can we see this working, and what role does assessment play? When planning for cognitively challenging learning, assessment planning should reflect the priorities for all other aspects of learning.

A strategic approach to assessment which supports cognitively challenging learning environments

When considering the place of assessment in education, teachers must be clear about:

- What they are trying to assess;

- How they plan to assess;

- Who the assessment is for;

- What evidence will become available;

- How the evidence can be interpreted;

- How the information can then be used by the teacher and the pupil;

- The impact the information has on the planned teaching and learning;

- The contribution assessment makes to cognition, learning and development.

Effective assessment is integral to the provision of cognitively challenging learning experiences. With careful and intentional planning, we can assess cognitive challenge and its impact, not only for the more able pupils, but for all pupils. Assessments are used to measure the starting point, the learning progression, and the impact of provision. When working with more able pupils, in cognitively challenging learning environments, the aim is to extend assessment practices to include assessment of higher-order, complex and abstract thinking.

When used well, assessment provides the teacher with a detailed understanding of the pupils’ starting points, what they know, what they need to know and what they have the potential to do with their learning. The teacher can then plan an engaging and exciting learning journey which provides more able pupils with the cognitive challenge they need, without creating cognitive overload.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has joined with others to recognise the importance of cognitive science to inform interventions and classroom practice. Spaced learning, interleaving, retrieval practice, strategies to manage cognitive load and dual coding all support cognitive development – but are dependent on effective assessment practices which guide the teaching and learning. The best assessment methods are those that integrate fully within curriculum teaching and learning.

Assessment and classroom management

It is important to place the learner at the centre of any curriculum plan, classroom organisation and pedagogical practice. Initially the teacher must understand the pupils’ strengths and weaknesses, together with the skills and knowledge they possess, before engaging in new learning. This understanding facilitates curriculum planning and classroom management, which have been recognised as essential elements of cognitively challenging learning. Often, learning time is lost through additional testing and data collection, but when working in cognitively challenging environments, planned learning should be structured to include assessment points within the learning rather than devising separate assessment exercises.

When assessing cognitively challenging learning, pupils need opportunities to demonstrate their abilities using analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. They must also show how they use their existing knowledge in new, creative, or complex ways, so questions might include opportunities to distinguish between fact and opinion, to compare, or describe differences. The problems may have multiple solutions or alternative methodologies. Alternatively, pupils may have to extend learning by combining information shared with the class and then adding new perspectives to develop ideas.