Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

maths

confidence

English

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Neil Jones,

07 September 2020

|

Neil Jones, NACE Associate

This article was originally published in our “beyond recovery” resource pack. View the original version here.

In the context of “recovering” teaching and learning at secondary level, I want to suggest that the principles of working with the most able learners remain the same. The crisis – as crises do – has provoked polarised responses: Tiggerish optimism about opportunities to change the way education works on the one hand; Eeyorish despair on the other, doubting whether anything can be recovered during or after this hiatus.

There is no doubt that this crisis has brought disasters with it for young people and their secondary education. But crises reveal, in a sharp and heightened way, what is already the case. It remains the case that schools need:

- To include the most able students explicitly in their thinking, for those students’ benefit and the benefit of all;

- To use current technology (the word “new” gives away how slow we can be), intelligently and responsively, to enable excellent work from the most able students, independently and collaboratively;

- To remember that teaching and learning, with the most able and with all students, is fundamentally a human relationship, not a consumer transaction.

Below are some suggestions that you may already be considering as you gear up to get back into the secondary classroom.

1. Take “accelerated learning” seriously – but don’t use it as “cramming”.

Tony Breslin, in the draft preface of his forthcoming book Lessons from Lockdown: the educational legacy of COVID-19 (Routledge, to be published end of 2020 / beginning of 2021), writes: "from a societal and educational standpoint, post-virus rehabilitation is not about how quickly we can get back to where we were. Nor is it about reconstituting our schools in the image of ‘crammer’ colleges, obsessed by catch-up and curriculum recovery, as if all the last few months have left us with is a shortcoming in knowledge and a loss of coverage." [Emphasis mine]

This is an important point, worth serious reflection. Teachers and most parents will understandably be anxious to make up for lost time and lost learning, particularly those whose children and students are at the pinch points of transition between key stages. Breslin continues: "Rather, it is about how far we can travel in light of our shared experience, and the different educational and training needs that will surely manifest themselves in the years ahead. It is also about acknowledging those longstanding shortcomings at the heart of our schooling and education systems, around persistent inequalities of outcome, around the need to build inclusion and attainment alongside each other rather than posing them as different and sometimes conflicting opposites, and around attending to the wellbeing of children, their families and all who support their learning – as if we could build a sustainable education system without doing this." [Emphases mine]

Most teachers would agree, surely, with the wisdom here. “Cramming” or force-feeding our students course content as if we were fattening geese, would be horribly stressful, and pedagogically ineffective in the long term. Yet there is an opportunity for us, instead of “cramming”, to take accelerated learning very seriously indeed.

In his article exploring current priorities and opportunities for primary schools, NACE Associate Dr Keith Watson highlights Mary Myatt’s insistence on professionals paring back course content to the essentials. He is, of course, right to point out the dangers of narrowing the curriculum even further. As an English teacher, I understand why the GCSE exam boards have elected to remove poetry from the exams, but it chills my blood to think of the lost potential for thought, feeling and understanding that this represents – particularly for our more able students.

I do wonder, though, whether we now have an opportunity to introduce just a little more urgency – but not panic – into teaching and learning. Accelerated learning strategies aim to achieve both inclusion and attainment in learning, in the ways that NACE has advocated for so many years: help your most able students to go as far and fast as they can; teach to the top, support from the bottom, and so on. This approach should still be used; we will just have to use it on less material. Don’t over-rehearse, i.e. don’t plan to teach new Year 10 students six months of missed Year 9 course content first. Do over-learn, with regular, no-stakes tests to embed knowledge and build confidence and mastery. Crucially, teach what needs to be taught now and scaffold knowledge and skills “just in time.”

A document that has garnered interest, originating from the US, is the Learning Acceleration Guide published by TNTP. Like anything, you’ll not want to swallow it wholesale, but it does give a range of sensible suggestions, including those set out above. The main thrust is that we should not panic about teaching new material, as if the students will never be ready for it. Instead, teaching new and necessary material, if scaffolded, can prompt memory of previous learning and help students “catch up” by stealth, rather than by “remedial action” that brings their learning up to speed to where they should have been, rather than where they could be now. This is clearly a leading attribute of the challenging classroom at any time in history, pre- or post-COVID. 2. Be bold with remote learning – “homework” could be transformed.

You may have found yourself cursing Zoom, Loom, Vidyard, Microsoft Teams or Google Classroom at several stages over lockdown; or you may have been excited to learn how to use them, because you had to. Most likely, like me, you felt both. But I can’t complain any longer that I don’t have time to learn about “flipped learning”. For those students with access to a laptop, we should continue to experiment with how far we can enable students to work independently and with each other. Again, this is an opportunity for us to make a virtue of necessity.

At our school, and I’m sure at yours, our departments have put in place planning and resources that can be both taught in the classroom and remotely. A lot of labour has been put into producing packs of work. For the more able students, however, we mustn’t stop offering exciting invitations to push their interest further.

For the last two years, I’ve been able to group the most able students by subject and year cohort and set them up to research and write up their own projects, guided by their interest. I have been impressed and inspired by how well I could trust students to be “entrepreneurial” in their independent work, supported pretty minimally by caring subject specialists, but a lot by each other. We use Microsoft Teams to enable this, and I would point you to Amy Clark’s blog post on this topic for further possibilities in using Teams. See too, the recorded NACE webinar on using technological platforms to develop independence (member login required).

Our students, in these times and in all times, should be putting in at least as much creative labour as their teachers. A remarkable result of more enforced student independence is how much more we can trust them to adapt, re-combine and invent new responses to the information and tasks we give them. Many students, at all key stages, are adept at using technology in a way that most of their teachers haven’t been.

Consider, too, how you can use technology to gather student voice so that you know how your most able students are faring; and even better, garner suggestions from them of how they would like to extend the curriculum, so that they feel they have a say in the direction of educational travel. As always, these students’ insights into their experiences of teaching and learning bring us priceless information on what’s going well and what’s not. Online platforms make this process so much easier now.

3. “Humanity first” – but that doesn’t necessarily mean “teaching second”.

Barry Carpenter’s work on the very notion of a “recovery curriculum” has received widespread coverage among school leaders and teachers. At one stage in his talk for the Chartered College of Teaching, Carpenter urged teachers to “walk in with your humanity first, and your teaching skills second.” In the context of the therapeutic, wellbeing-centred vision for recovery from the shocks and anxieties of the last year, this clearly makes sense. With more able students in mind, however, and especially the exceptionally able students we teach, we must remember that study is an intrinsic part of their humanity: they are one and the same thing.

Again, then, crisis reveals what is already present. Our more able students will still need to know, in their relationships with their teachers and with supportive peers, that it is cool to be clever, interesting to be interested, exciting to be excited by the discoveries involved in learning. They do not need to be glum, or despair that they have stopped learning, because we can be confident that we are always learning if we have a mind to, and seek – as Dr Matthew Williams advocates – to turn work into study.

Those interesting questions that we pose; that palpable delight in our own subject interest; those personalised phrases of praise; the hints and foretastes of exciting future study and work – all those confident connection-points with our more able students are always vital, and continue to be so as we all move forward into an uncertain “first term back”. I found at the end of the summer term, teaching small bubble-groups of sixth formers, that they were desperate to talk and explore what was going on. So was I! This is clearly no surprise. The teaching skill required here will be to move between the personal and the abstract, as it always is in pedagogy worth the name.

Our most able students often think and feel things at a greater intensity. Managing this intensity with the general intensity of the overall experience of socially distanced schooling will take skill and humanity – but we as teachers are not in uncharted waters here: it is what we do under normal circumstances, too.

Join the conversation: NACE member meetup, 10 September 2020

Join secondary leaders and practitioners from across the country on 10 September for an online NACE member meetup exploring approaches to the recovery curriculum and beyond. The session will open with a presentation from NACE Associate Neil Jones, followed by a chance to share approaches and ideas with peers, reflecting on some of the challenges and opportunities outlined above. Find out more and book your place.

Not yet a NACE member? Starting at just £95 +VAT per year, NACE membership is available for schools (covering all staff), SCITT providers, TSAs, trusts and clusters. Bringing together school leaders and practitioners across England, Wales and internationally, our members have access to advice, practical resources and CPD to support the review and improvement of provision for more able learners within a context of challenge and high standards for all. Learn more and join today.

Tags:

collaboration

curriculum

independent learning

KS3

KS4

lockdown

remote learning

technology

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Emma Tibbitts,

07 September 2020

|

Emma Tibbitts, NACE Associate

This article was originally published in our “beyond recovery” resource pack. View the original version here.

There are many challenges for EYFS settings this September. It has not been possible to make the usual extensive preparation that would have been carried out to support transition for children, parents and carers. Assessment sharing has been reduced, and with limited or non-existent opportunities to meet new children and families, practitioners will have very limited knowledge of each child. Added to this, many children will have higher anxiety levels than usual around change and separation from families this year, while the lengthy period of social distancing has heavily compromised opportunities to develop relationships, especially for the youngest children.

Government guidance for school reopening states:

“For children in nursery settings, teachers should focus on the prime areas of learning, including: communication and language, personal, social and emotional development (PSED) and physical development. For pupils in Reception, teachers should also assess and address gaps in language, early reading and mathematics, particularly ensuring children’s acquisition of phonic knowledge and extending their vocabulary.” – Guidance for full opening: schools (updated 7 August 2020)

Due to pressure to prioritise vulnerable and low-ability pupils, it is likely that many settings will have placed little emphasis on preparing to identify and support the more able. This is not new. At NACE, we regularly hear from school leaders and practitioners who are striving to improve provision for highly able young people but who face barriers to doing so, and this September will be no exception!

It remains important to address the myths and misconceptions surrounding this group, and to continue to ensure that even our youngest more able pupils are not overlooked, as they too are entitled to a high-quality education. Without appropriate challenge (too low, or too high or unsupported), a learner’s motivation levels will drop, frustration is increased, and children become in danger of coasting.

- Providing for more able learners is not about labelling, but about creating a curriculum and learning opportunities which allow all children to flourish.

- Ability can be revealed across a range of specific domains or more generally, and not only in traditional academic subjects.

An effective EYFS learning environment which carefully plans for and reflects the seven areas of learning is an excellent foundation for providing children with a variety of rich learning opportunities. However, current hygiene guidance will impact on the range and type of resources practitioners can now safely provide.

Could this be viewed as an opportunity to adopt a fresh creative licence to use and develop your practice in planning for a greater repertoire of open-ended activities? Research within EYFS shows that using the same resources in a variety of ways is effective in challenging pupils to develop their metacognition, similar to the principle of the mastery approach of “finding many different ways”.

The following set of questions could be helpful to think through when planning for or setting up a challenging learning activity:

- Does it reflect the interests and curiosity expressed by children?

- Have you spent time predicting how the children might interact with the resources you provide?

- How will you present the resources in an open and accessible way?

- How could you re-use familiar resources in different ways?

- How many opportunities will this activity give to enable children to make links to other learning or their own ideas?

A strong emphasis is also being placed on opportunities to learn outdoors, supporting requirements to ensure that only small groups of children are present at any one activity at a time. The government guidance reminds practitioners to “Consider how all groups of children can be given equal opportunities for outdoor learning.”

Maximising outdoor learning time presents a perfect opportunity to develop outdoor provision – a brilliant platform for planning in challenge and open-ended activities for more able learners too. Outdoor learning has always been valued and the EYFS curriculum highlights the importance and value of carefully planned, daily outdoor experiences for children’s physical learning and development. Frequent outdoor learning challenges give children the power to change their perspective – a key underpinning that fosters natural curiosity, active learning, playing and exploring, critical thinking, and creative problem solving – all the things children need to learn how to learn, as stated in the EYFS characteristics of effective learning.

In summary, it is right that much effort should continue to be focused on children’s wellbeing, but we must also ensure that all children (including the more able through quick and effective identification) are given the opportunity to meet their full potential on return to school in September.

Although some “normal” practice will need to be reviewed in order to meet COVID-19 guidance, the preparation and delivery of a broad and ambitious curriculum must not be delayed. There could be serious setbacks to children’s progress if too much emphasis is placed on proposed “catch-up curriculums”, particularly within the reception phase as this is the first stage of formal education for these children.

Unlike other year groups, our new school-starters won’t have missed out on any formal teaching prior to September. We know that it is our very youngest children that have the potential to develop at astonishing rates. It is at this stage where neural pathways need to be built which will enable them to make connections in their learning.

Get set to embrace these incredibly thirsty young learners, an opportunity that should not be missed!

Further questions to consider:

- How will you provide for the emotional needs and wellbeing of the children whilst ensuring that learning content is not delayed unnecessarily?

- How do you plan to identify more able learners starting with you this term?

- How will you need to adjust your physical learning environments to ensure compliance to guidance whilst still seeking to maximise learning engagement, including challenge?

- What is the vision for your setting? Where do you hope the children will be by the end of the half-term? How do you plan to achieve this? How will you ensure you have a clear direction, with the flexibility to respond to barriers imposed by the pandemic and the individual needs of all learners, including the more able?

Join the conversation: NACE member meetup, 15 September 2020

Join primary and EYFS leaders and practitioners from across the country on 15 September for an online NACE member meetup exploring approaches to the recovery curriculum and beyond. The session will open with a presentation from NACE Associate Dr Keith Watson, followed by a chance to share approaches and ideas with peers, reflecting on some of the challenges and opportunities outlined above. Find and more and book your place.

Not yet a NACE member? Starting at just £95 +VAT and covering all staff in your school, NACE membership offers year-round access to exclusive resources and expert guidance, flexible CPD and networking opportunities. Membership also available for SCITTs, TSAs, trusts and clusters. Learn more and join today.

Tags:

early years foundation stage

lockdown

physical education

resilience

transition

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

07 September 2020

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Associate

This article was originally published in our “beyond recovery” resource pack. View the original version here.

Whilst primary schools share some of the general issues faced by all phases following the pandemic, there are specific aspects that need to considered for more able primary pupils. Research on the impact of the pandemic is still in its infancy and inevitably still speculative; while other catastrophic events such as the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, are referred to, the pandemic is on a far greater scale and the full impact will take time to emerge.

What, at this stage, should primary school leaders and practitioners focus on to ensure more able learners’ needs are met?

1. Do: focus on rebuilding relationships

When pupils return to school the sense of community will need to be re-established and relationships will be central to this process. Pupils will need to feel safe and secure in school and the return to routines and robust systems will help with this. Not all more able pupils will have had the same experience both in terms of learning and home life. As always, creating a supportive learning environment will be vital.

2. Do: provide opportunities for reflection and rediscovery

All pupils need the opportunity to tell their lockdown stories and more able pupils should be encouraged to do so using their talents – whether written, artistically, through dance or other means. How best can they express their feelings over what has happened? This will allow them to come to terms with their experiences through reflection but also allow thoughts to turn positively to the future. In this sense they will be able to rediscover themselves and focus on their hopes for the future.

3. Do: use positive language

A key question (as they sing in Hamilton) is “What did I miss?” What are the gaps in learning and what is the school plan for transitioning back into learning generally and then with specific groups? We need to be careful of negative language; even terms like “catch up” and “recovery” risk suggesting we will never make up for lost time. Despite the challenge, we need to show our pupils and parents how positive we are as teachers about their future.

4. Do: find out where your pupils are

Each school will want some form of baseline assessment early in the year, whether using tests or more informal methods. Be ready to reassure more able pupils who perhaps do not achieve their normal very high scores on any testing. For more able pupils a mature dialogue should happen using pupil self-assessment alongside any data collected. Of course, each child is different and it is crucial that teachers know the individual needs of the pupils.

5. Don’t: overlook the more able

There is a danger here of the unintended consequence. The priority is likely to be given to pupils who have fallen even further below national expectation and this could lead to teachers having to divert even more time, energy and focus to these pupils at the expense of giving attention to more able pupils who may be deemed not to be a priority. More able pupils must not be neglected in this way due to assumptions that they are “fine” in terms of emotions and learning. They need to be engaged in purposeful learning and challenged as always.

6. Don’t: narrow your curriculum

Mary Myatt has previously talked of the “disciplined pursuit of doing less” and the pandemic is leading to consideration of the essential curriculum content that needs to be learned now. It may force schools to be even clearer on key learning, but we need to be careful of even greater narrowing of the curriculum, especially to test criteria. The spectre of “measurement-driven instruction” is always with us, particularly for Year 6.

7. Do: focus on building learners’ confidence

Pupils need to be settled and ready for learning, but this is often achieved through purposeful tasks. Providing more able pupils with the chance to work successfully on their favourite subjects as soon as possible can build confidence. It may be that pupils who are able across the curriculum have subjects where they fear having fallen behind more than in others. Perhaps they are very strong in both English and maths but worry about not excelling in the latter, and therefore feel concerned that they have fallen behind. It is important to gauge their feelings across the curriculum, perhaps through them RAG rating their confidence; this could then lead to individual dialogue between teacher and pupil regarding how to rebuild confidence or revisit areas where they perceive the learning is weaker. Learning is never linear; this needs to be acknowledged and pupils reassured.

8. Do: review your writing plan for the year

Teachers will be mindful of the challenges of achieving the criteria for greater depth, particularly in relation to the writing. It will be important to review the normal writing plan for the year to see that the key tasks are still appropriate and timed correctly. What does the writing journey look like throughout the year to achieve greater depth and will the normal milestones be compromised? The opportunity to experiment with their writing is essential for more able pupils, so when will this happen? Teachers in all year groups must not panic about the demanding standards needed, but instead remember they have the year to help their pupils achieve those standards, even if current attainment has dipped.

9. Do: review and adapt teaching and learning methods

The methods of teaching more able pupils will also have to be considered in the changed learning environment. Collaborative group work may be more challenging with pupils often sitting in rows and also having less close proximity to their teacher. A group of more able pupils crouched around sugar paper designing the best science experiment since the days of Newton may not currently be possible. But dialogue remains vital and time still needs to be made for it despite restrictions on classroom operations.

10. Do: remain optimistic and ambitious

We must remain optimistic for our more able pupils. We must not shy away from the opportunities to go beyond the curriculum to encourage and develop talents. More able pupils need to have the space to show themselves at their best. The primary curriculum provides so many opportunities for more able pupils to push the boundaries in the learning beyond the narrow confines of subject areas. This can be energising. The London School of Music and Dramatic Arts (LAMDA) proudly declares its students to be:

- Creators

- Innovators

- Collaborators

- Storytellers

- Engineers

- Artists

- Actors

We can also add athletes and many more to this list. More able pupils need to develop their metacognition and seeing themselves in some of these roles can inspire and motivate them. Remember though, creativity can’t be taught in a vacuum. It needs content so that the creativity can be encouraged.

Given that the “recovery curriculum” may spend a lot of time re-establishing a mental health equilibrium and helping those with large gaps in knowledge to “catch up”, it may be that those more able pupils who are ready for it can be given license by teachers to experiment more with the curriculum, have more independence and get to apply their learning more widely.

Not merely recovering, but rebounding and reigniting with energy, vigour and a celebration of talents.

Join the conversation: NACE member meetup, 15 September 2020

Join primary leaders and practitioners from across the country on 15 September for an online NACE member meetup exploring approaches to the recovery curriculum and beyond. The session will open with a presentation from NACE Associate Dr Keith Watson, followed by a chance to share approaches and ideas with peers, reflecting on some of the challenges and opportunities outlined above. Find out more and book your place.

Not yet a NACE member? Starting at just £95 +VAT and covering all staff in your school, NACE membership offers year-round access to exclusive resources and expert guidance, flexible CPD and networking opportunities. Membership also available for SCITTs, TSAs, trusts and clusters. Learn more and join today.

Tags:

assessment

confidence

curriculum

feedback

KS1

KS2

leadership

lockdown

metacognition

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Robert Massey,

01 September 2020

|

Robert Massey, author, teacher and lead for high-attaining students, shares his “three Rs” for the return to school.

The ‘new normal’ is full of contradictions. As teachers and students prepare to return to schools this September, we face a unique set of challenges. Much will be new, but some of what we do will look familiar and reassuring; a lot will be strange as we navigate physical barriers such as one-way systems and Perspex screens and the technological challenges of virtual meetings, but at the heart of what we do will be lessons and learning. Same old, same old.

Some schools have used the work of Barry Carpenter on a ‘recovery curriculum’ as a helpful way of thinking about the new term ahead, and I hope that the points which follow about language, mapping and high expectations are useful as suggestions towards a way of thinking about what the ‘new normal’ might mean.

Recovery: words matter

The language which schools and teachers use in the first term back will be vital in setting the tone for learning. It will be so tempting to resort to good old standby phrases used in the past following, for example, periods of pupil illness or teacher absence.

“We’ve got tons to catch up on!”

“We’ve missed months of learning since March.”

“You’ve had all this lockdown time to get the work I set you done.”

This is unhelpful for many reasons. It will serve to heighten anxiety among students, some of whom will already be worried about what they’ve missed, and more nervous than they may let on about what the future may hold. It will imply that responsibility for the ‘lost learning’ somehow rests with them. It will depersonalise the classroom experience: we’re all in this together, and we’re all ‘behind’.

Heads and senior leadership teams can take a lead here by sanitising such language from the classroom, and by sharing more positive phrases with parents. A recovery curriculum might be framed around metaphors of building:

“I’m just checking that we have strong foundations of learning in biology by revisiting cell structure.”

“Now we’re reinforcing the use of key terms in poetry that we’ve used before.”

“How as a class can we build upon last year’s work on Tudor monarchy as we move on to look at revolution and civil war?”

Reassurance: mapping the learning journey

This is not mere window dressing and pretty words. I’m going to be spending time with Year 9 mapping where they are as learners. If I don’t know where they are now, I can’t set out a learning journey for this term, still less beyond. Each pupil will need individual reassurance that I know where they are and where they can get to. This will take time and will mean less time to deliver content, but that is a sacrifice worth making this term of all terms. Reassurance, reassurance, reassurance is what I’ll be offering to my Year 13s faced with the traditional UCAS term on top of uncertain A-level assessment outcomes. Small steps will be my building blocks, starting from the here and now rather than what might have been, with big topics broken down into smaller and accessible chunks of learning which can be more easily monitored and supported should lockdown return.

A recovery curriculum is a joined-up piece of collective thinking shared across a school. There has never been a greater need for departments to look closely at how they link with others. Pupils and parents will be confounded if, to take a very simple example, the English department puts in effort to focus on the wellbeing of students by revisiting key skills and encouraging the articulation of doubts and fears about the current situation, while in maths the emphasis is immediately on tests just before half term and ‘filling in gaps’ missed in past months.

- How will your department work together to share approaches to recovery and reassurance?

- How will your faculty and school build shared attitudes and actions to support pupils’ return?

Remarkable students

I’m therefore emphasising for September the importance of pupil wellbeing and the reassurance of parents and colleagues. This does not mean a lowering of expectations. As children learn from our modelled attitudes and actions that the ‘new normal’ is more normal than new, they will understand that it is natural for us as teachers to set the bar of learning high, just as we used to do.

We are not revisiting, rebuilding and reinforcing past learning in order to stand still and stagnate, but rather are doing so as a springboard for the skills and content still to come. Think of it as recovery revision ready for new challenges ahead.

If I am teaching to the top with my Year 10s this term, as I hope I am, I will be doing them no favours if I simplify core content or fail to stretch them in discussion. The challenge for me will be to do this alongside the mapping and reassurance they need. So:

- I’m building in more signposting: this is where we are, and the next three weeks will look like this.

- I’m increasing ‘hang back’ time as the lesson ends, so that students can catch me or I can speak to them individually.

- I’m reviving a pre-lockdown good habit of three Friday phone calls home to spread the message of reassurance, praise and high expectations.

Summary

The three aims stated above will need careful balancing and blending. Context is everything, and you know your students better than anyone else, so you can judge and provide the scaffolding and support needed for each class and each pupil. This will be a rollercoaster recovery term, where the language we use to map our learning journeys will matter a lot. Equally, the one-to-one reassurance we offer has never been more important. This recovery curriculum needs to remain ambitious, with teachers teaching to the top – combined with a culture of high expectations continuing from pre-lockdown days. Remarkable teachers will model this curriculum for our remarkable students.

Further reading:

Robert Massey is the author of From Able to Remarkable: Help your students become expert learners (Crown House Publishing, 2019). For a 20% discount when purchasing this or other Crown House publications, log in to view our current member offers.

Tags:

confidence

curriculum

leadership

lockdown

parents and carers

resilience

retrieval

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Chris Yapp,

26 August 2020

|

This blog post is based on an article originally published on LinkedIn on 16 August 2020 – click here to read in full.

The fallout from A-level and GCSE results will be uncomfortable for government and upsetting and challenging for teachers and students alike. Arguments over whether this year’s results are robust and fair miss one key issue.

Put simply: "Has the exam system in England ever been robust and fair for individual pupils?"

For those of us who did well in exams and whose children also did well, it is too easy to be confident. Accepting that our success and others’ failure is a systemic problem, not a result of competence and capability, is not easy.

Let me be clear: I do not have confidence in the exam system in England as a measure either of success or capability.

[…] Try this as a thought experiment. Imagine that I gave an exam paper submission to 100 examiners. Let me assume that it "objectively" is a C grade.

Would all 100 examiners give it a C? If not, what is the spread? Is the spread the same for English literature, physics and geography, as just three examples? If you cannot provide clear evidenced answers to these questions, how can you be confident that the system is objective?

If we look at the examiners, the same challenge appears. Are all examiners equally consistent in their marking, or do some tend to mark up or down? Where is the evidence, reviewed and published to demonstrate robustness?

We also know that the month you are born still has an effect on GCSE grades. What is robust about that?

[…] I have known children who have missed out on grades after divorce, separation and death of parents, siblings and pets. I cannot objectively give a measure of the impact, but then neither can the exam system. I would add that I suspect a classmate of mine missed out because of hayfever. Children with health issues such as leukaemia and asthma whose schooling is disrupted have had their grades affected every year, not just this one.

So, the high stakes exam system is, for me, a winner-takes-all loaded gun embedding inequality and privilege in the outcomes.

Can we do better? Well, if we want to use exams, then each paper needs to be marked by say five independent assessors. If they all agree on a "B" then that is a measure of confidence. This is often a model used for assessing loans, grants and investments in businesses. It does not guarantee success of course, but what it does is reduce reliance on potentially biased individuals. If I was an examiner and woke up today in a foul mood, would I mark a paper the same today as yesterday? I would not bet on it.

The really interesting cases in my experience are where you get 2As, a C and 2Ds, for instance. In my experience, I've seen it more often in "creative subjects", but some non-traditional thinkers in subjects like mathematics (a highly creative discipline, by the way) often don't fit the narrow models of assessment of our exam system. The problem with this example of bringing people together to try get a consensus on a "B" is that it eliminates the value that comes from the diverse views and the richness of the different perceptions.

So, for me, for a system to be robust it has to have more than one measure to allow the individual, parents, universities, FE and employers access to a richer view of an individual. If someone got an ABBCD in English that is as interesting as someone who got straight Bs.

[…] There are already models that command respect in grading skill levels. Parents are quite happy if a child is doing grade 6 piano and grade 2 flute at the same time. They are quite happy for a child to sit when ready and have the chance to resit. Yet in the school setting the pressure is there for a child to be at level 8 say for all subjects. That puts unnecessary pressure on pupils, teachers and schools.

Imagine how society would react if you could only take the driving test once at 17 and barriers were raised to stop you retaking it.

[…] This year’s bizarre algorithmic system is not robust, but then we have never had a robust system as far as I am concerned. Let's open our eyes and build something that we should have more confidence in. Carpe diem.

Join the discussion: share your views in the comments below (member login required).

Tags:

assessment

disadvantage

KS4

KS5

lockdown

policy

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elaine Ricks-Neal,

13 July 2020

|

NACE Challenge Award Adviser Elaine Ricks-Neal shares seven key questions to help schools, teams and departments review their use of digital learning and plan for continued development.

Recent events, through necessity, have catapulted schools into a change of existing practice to meet the challenges of remote learning. An interesting outcome has been the rapid increase in skills and confidence levels of many teachers in the use of digital learning technologies and with it a growing enthusiasm to explore the potential of technology to really transform the way we teach and how pupils learn. Through effective use of digital platforms, tools and apps, many schools have enabled pupils to access the curriculum in rich and engaging ways, signposting pupils to quality online resources they can use independently, encouraging collaborative learning and finding ways to personalise learning and feedback to pupils, often with the added bonus of greater involvement of parents in that process.

With this unprecedented level of teacher, pupil and also parental engagement with technology, is this now the time for schools to revisit their vision for digital learning, providing a structured opportunity for colleagues to reflect on what has worked well and next steps? Below are seven key questions for teachers, phase teams, departments and schools.

Note: Remember to keep the focus on the impact on learning; don’t be side-tracked by looking at digital resources in isolation.

1. What has worked well?

Set aside dedicated time to share the digital resources and approaches you have used, commenting on the quality of the materials and how they supported your learning objectives. What worked well? How do you know? What could be the next steps?

2. How can curriculum and lesson plans be adapted?

Look at curriculum plans and learning objectives and identify where in the planning phases you could use digital learning. Be clear about why and what the learning impact would be. For example, increased cognitive challenge and access to complex material in class and home learning? Developing pupil independence? Are there distinctive opportunities for your most able pupils?

3. How can we involve pupils as partners in digital learning development?

Discuss how you can explore the impact of approaches through consulting pupils about what they see as the benefits, possible pitfalls and opportunities of using technology to help them learn. How can the pupils’ own skills now be further developed? Consider setting up a focus group of able pupils to monitor the impact of new approaches.

4. Are there opportunities to work with parents more effectively?

Make the most of the high levels of recent parental engagement to consider any new opportunities presented by digital learning to help parents engage with and support their children’s learning at home and in school. Workshops on learning platforms and online resources available to support their child’s learning? Seeking their own views on the recent remote learning experience?

5. What are the digital skills that teachers now need to develop?

To build on newly grown/growing confidence levels, identify future skills and CPD needs individually, as a department, and as a school.

6. Do we now want to revisit our vision and policy?

Use the discussions as a basis to revisit your teaching and learning, more able and/or other relevant school policies. Is the vision for the use of technology to impact on teaching and learning fully articulated and agreed by all colleagues? Do you want to add new commentary on aims or provision?

7. How do we plan for continuous improvement?

Plan strategically from your discussions, integrating your action points into school improvement plans, and being clear about how the actions will be implemented, resourced and reviewed for impact.

The review discussion can feed into the broader whole-school vision of the transformative potential of technology to drive innovation and create autonomous learners who have the digital skills which are vital in today’s world.

Coming soon: new guidance on digital learning and the NACE Challenge Framework

Element 3 of the NACE Challenge Framework focuses on curriculum, teaching and support; it includes a requirement for schools to audit how effectively their vision for using technology translates into improved daily practice within and outside the classroom. In the autumn term, a new Digital Learning Review and Forward Planning Tool will be available for schools working with the Challenge Framework to support a review of current policy and provision in the use of digital learning.

Tags:

Challenge Framework

independent learning

parents and carers

policy

remote learning

self-evaluation

technology

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By The Bromfords School & Sixth Form College,

03 July 2020

|

Amy Clark, Assistant Headteacher for Quality of Education, explains how The Bromfords School and Sixth Form College has used Microsoft Teams to support both students and staff – delivering remote learning, pastoral support and peer-led CPD.

Being thrust into the world of remote learning has galvanised us to dig deep as a profession and do what we do best: find ways to make learning enjoyable – even in the toughest of times. At The Bromfords School, a small group of us had already been trialling the use of Microsoft Teams with our sixth form pupils to enhance the provision they were receiving, with the focus on enabling students to participate in a learning-rich environment without having to be in the classroom. Students loved having access to a digital learning space, outside of school, that they could use to have academic debates on key topics, share links to wider reading or resources and generally support each other in a collaborative way.

We also saw Teams as a way for staff to share best practice CPD. We all know what happens when you attend an amazing INSET day or twilight session; you eventually find time to do planning and create some wonderful resources that you share with colleagues, but they get lost amongst the mass of emails, meaning the brilliant work done often gets lost. The plan was to use Microsoft Teams to provide a specific space for professional dialogue about teaching and learning, where teachers could share resources, upskill each other and continue to develop as professionals.

Then along came COVID-19 and thrust our plans forward…

Using Teams for academic, pastoral and peer support

Even though the timeline for rolling out Microsoft Teams across the school was sped up, our staff certainly rose to the challenge. Whilst Teams isn’t the only software we have used to communicate remote learning to students, it is quickly becoming a space that students use for both academic and pastoral purposes.

Tutor group channels were set up on Teams for every year group, where tutors have been able to ‘check in’ each week with pupils. This has ensured that students’ academic needs are met, that students have access to advice should they need it, but most importantly, tutors could keep track of students’ mental wellbeing. Open lines of communication meant that if a child was struggling, we could support them. Students didn’t know how to work remotely, how to organise their time or how to be self-motivated; our use of Teams has provided them with methods for easy communication with an adult they are familiar with on a daily basis.

We hope that by having the lines of communication open to students and having a compulsory check-in each week, the bridge between students working in isolation at home and returning back into the building is eased and that that we are able to lower anxiety for our students.

Our Teams CPD channel has supported staff not only in developing their IT skills to enable the best possible provision for students, but also in accessing a range of ideas they might not have come across before. Our channel has ‘How to…’ videos on topics including the use of narrated PowerPoints, quizzes or forms on Teams, how to use ‘assignments’ within Teams and mark these using a rubric to give feedback on the work completed, to name just a few. Staff have also shared information on how to create drop-down and tick-boxes in Microsoft Word, where to go to get icons for dual coding, methods for increasing student engagement and other concepts that will improve remote learning.

Even staff members who are self-proclaimed ‘technophobes’ have been able to develop their IT skills to ensure the digital learning process for our pupils is as strong as it can be. The channel has enabled everyone to feel like we are all in this process together, all learning together – and nothing is as daunting when you have others by your side.

Five core principles for effective remote learning

As a school, we were keen to ensure we were catering to the needs of all our pupils during this time, with our more able students being a key focus. We wanted to ensure the provision offered to this group remained high quality so they were able to continue to be challenged academically – avoiding the dreaded generic worksheet, a one-size-fits-all approach. We also found that many of our more able were struggling with managing workload, which developed increased levels of anxiety.

A group of leaders and I developed what we felt were the five core principles of remote learning and delivered this to staff through CPD meetings, to ensure our more able students were academically and emotionally supported.

We felt that remote learning should be:

- Concrete: it should have a clear purpose and learning intent that fits with the wider curriculum. There should also be clear timings for tasks so that students do not spend excessive amounts of time on projects.

- Inclusive: consider how you stretch your most able students by providing links to wider reading, podcasts, challenge tasks or breadth of choice such as presentation methods.

- Considerate: taking into consideration students’ learning environments and access to materials they could need. Also planning tactically so that students do not become overwhelmed with the sheer amount of work expected of them.

- Reflective: students should have feedback at key points and self-assessment opportunities through sharing clearly defined success criteria.

- Engaging: staff should incorporate a range of learning activities and software to avoid students becoming demotivated. Also focusing on mechanisms for praise so that students know their hard work is being recognised.

The concepts here are not new. But when staff are also dealing with the pressures and anxiety a COVID-19 teaching world presents, it is a timely reminder that the core principles of teaching must remain so that students can continue to succeed. The five core principles listed above all aim not only to enrich the remote learning a student receives, but also take into consideration students’ mental wellbeing too.

When we return to school, I hope the lessons learnt from using technology during this time do not get lost. Many members of staff have told me how much they have enjoyed using Microsoft Teams to support learning and how they will continue to use it moving forward, particularly to aid collaborative work with peers and to support home learning. Our eyes have been opened to the potential of this technology in supporting and enriching the curriculum for more able students though many of the methods listed above. It has certainly provided both staff and students with a very different learning experience, with the potential to continue to enrich learning beyond the classroom for students and increase enjoyment in developing pedagogy for staff.

Read more:

Tags:

apps

collaboration

CPD

KS5

lockdown

pedagogy

remote learning

technology

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Christabel Shepherd,

11 June 2020

|

Christabel Shepherd, NACE Associate and Trustee, and Executive Headteacher of Bradford’s Copthorne and Holybrook Primary Schools

Over the past few months, I have learnt a great deal about myself and, more importantly, about the conditions which are central to the effective education of the children in our schools.

In the two primary schools that I lead, home-learning during this crisis has taken two forms: printed packs of differentiated work for the core and wider curriculum (a mixture of practise, retrieval and application, as well as some new learning); and remote learning via the various sites and activities to which we have directed children (these include Mathletics, Times Tables Rockstars, White Rose Maths Hub, Accelerated Reader etc.). All of this has been supported with regular telephone check-ins with pupils and their parents/carers. The results in terms of pupil engagement have been mixed and, in turn, the impact on pupil progress is difficult to measure.

All good teachers know their children. They can spot immediately when a child has “zoned out”; one whose stress levels are increasing because they clearly don’t understand; the more able learner who is afraid to put pen to paper for fear of the work being incorrect or imperfect; or the student who is frustrated or bored due to insufficient challenge.

When children are at home, we are not there to pick up on these signals and support them appropriately, and it is not easy to spot these signs on a computer screen. Without this, it is more difficult to identify misconceptions and address them effectively and before they become ingrained; it is nigh on impossible to remind children to think back to the strategies they have been taught in order to choose the most effective one or to think about which “learning muscles” they will need to use for a task; it is much harder to encourage children to attempt a challenge and face possible failure without the culture of supported risk that we have so skilfully developed in our classrooms. Never has the need for that human interaction between teachers and pupils been so stark.

So, what can we do now to mitigate this and contingency plan for the future?

Metacognition and self-regulation

For months prior to the COVID-19 crisis, metacognition and self-regulation strategies had started to become a key focus for many schools. Much of what many excellent teachers already do by default has been given a name and its importance highlighted by the findings of evidence-based research. This has been widely shared through, for example, the work of the EEF, with more and more teachers beginning to see and understand the benefits of building these strategies into their everyday work.

Had this been going on for longer and such learning behaviours been entrenched in our children, I feel that the negative effects of lockdown would have been lessened. As it is, I feel that much more work needs to be done in this area. Many of our learners – especially in primary schools – are only at the start of their “learning how to learn” journey, so do not yet understand or have embedded the key metacognitive or self-regulation skills, nor in turn the levels of intrinsic motivation to enable them deal effectively with home learning. Whereas at school, we would have been praising children for thinking about and then using appropriate strategies, there is concern that – in many homes – children will be being praised purely for task completion rather than the way it was approached and their metacognitive strategies.

This has strengthened my view that the need for children to be taught metacognitive and self-regulation strategies should be made an even higher priority. By the way, I’m not talking about special “learning how to learn” slots in the timetable; I’m talking about those strategies being central to our pedagogy in every lesson. Although many teachers do this naturally, I believe that we must all make a conscious decision to do this, directly teaching and modelling those learning behaviours through our own practice and daily interactions.

At this point, I would like to mention parents. They are a piece of the metacognitive puzzle I feel is currently being overlooked. We engage them in workshops to help them support their child’s subject-specific learning, yet it is rare to hear of a school where work is being done to support parents’ understanding in this area in order to help make them real partners in their child’s learning. If we value metacognition for our pupils, then parents must be made partners in this too.

Remote learning

This has been on my mind a great deal. As we know, many children and their families do not have access to the internet, suitable devices, or both. However, where such provision is in place, I feel we can do better than the scattergun approach currently in place in some schools by considering the inclusion of some key features/approaches:

- Introduce the lesson or theme by speaking directly to all the children in the class via a web-based platform such as Teams, Zoom, Google Classroom etc. During this short meeting, the teacher does a general check-in with everyone and maybe even a quick starter with children holding up their answers on whiteboards. The teacher then sets the learning task – and this has to be very carefully considered.

- As part of this, the children are directed to a short, explanatory video such as those provided by the White Rose Maths Hub, Khan Academy etc. Whatever source is chosen, the key is to find examples where there is simplicity in terms of format and clarity of explanation, where children have the chance to practise what is being introduced, pause, review and then continue with the explanation. The production should not be at the expense of the quality of exposition. Teachers may even wish to make their own explanatory videos; these do not need to be “all singing, all dancing”, but must adhere to the school’s safeguarding policy.

- A specified time is then provided for the children to work on the set task. During this time the teacher is still available online so that pupils can ask for help or guidance.

- At the end of the time, the children return to the screen in – as necessary – smaller groups, to share what they have done and get instant feedback from the teacher. This Assessment for Learning is key as it allows for any misconceptions to be addressed quickly. Once this has been done, the next lesson can be in the form of the opportunity to practice and apply this learning through an online portal such as Mathletics, Learning By Questions, HegartyMaths etc., before the next live lesson is introduced.

There has been some scaremongering about not delivering live lessons remotely as it may leave teachers at risk of malicious allegations. Aren’t teachers just as much at risk of this in the classroom each day? In most instances remote learning allows us to record the session so that there is a clear log of what has taken place. Please do not think from this that I am saying we should deliver live lessons without careful consideration; but I do think that some remote contact between teacher and learners is essential.

Parents and carers

During this crisis, I have been metaphorically slapped in the face by the importance of parents and carers. Don’t get me wrong; I’ve always known they were important and I have always been proactive about ensuring – through the provision of workshops, letters home and open events – that they were able to support their children with homework. However, the notion of whether parents were in a position to “go it alone” when it comes to educating their children has never really been a consideration. This has now changed and it is something that is polarising concerns around the likely widening of the gap caused by social disadvantage.

This has made me realise that our approach towards parental engagement needs to change. This is currently still shaping up in my mind but I think we need to be far more strategic and passionate.

Initially, on a practical level, in a similar way that we do for pupils, we need to either prepare or signpost explanatory clips for parents covering each area of the curriculum so they have a resource available for reference and to help them feel more confident when home-educating. We have done this in the past for areas such as guided reading, but I think we need to go much further.

We will need to look, too, at how clearly and to what degree we share with parents our aspirations for their children. Has this been merely a paper exercise in the past, or part of the school’s mantra, rolled out for assemblies and on special occasions? Or is the heart of the school’s vision and ethos shared with passion, and its core explained? Do staff members have the opportunity to be open and honest about their own life and education journey to this point so that parents and children understand that education opens the doors of opportunity and helps to provide children with the cultural capital they need to succeed? Are we honest and open about the real difference each stage of a child’s education makes to their future, rather than making sweeping generalisations about this to parents? Have we truly explained, for example, why synthetic phonics and reading are so important? How often do we hold small discussion groups for parents, where we can drill down into the importance of education and their role in this?

These questions need to be posed to and explored by the whole school community in order for us to find the best way forward and ensure our reflections and learning from the lockdown period are put to good use.

On a personal level, lockdown has taught me the value of making time for both reflection and my own professional development. I have taken the opportunity to address this and as a result I see what I have been missing.

This article was originally published in the summer 2020 special edition of NACE Insight, as part of our “lessons from lockdown” series. For access to all past issues, log in to our members’ resource library.

Tags:

curriculum

leadership

lockdown

metacognition

parents and carers

remote learning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elizabeth Allen CBE,

11 June 2020

|

Liz Allen CBE, NACE Trustee

Listening in to over 200 school leaders, teachers and young people in online forums and in personal conversations, I am hearing a recurring theme: “Some children have done better without me teaching them.” Some teachers add, “…which is a worry.” Most are keen to explore the reasons why some children are thriving on home learning, when many appear to be struggling. While it is vital that the reasons for this struggle are identified and addressed, there is also much that school leaders and teachers can learn from the “rising stars” – young people who were not identified for a particular ability, skill or expertise in the classroom but who are blossoming at home, surprising their teachers.

Why were they not noticed in school? Why are they thriving at home? What can we learn from them, for our future practice, as we prepare for more students to return to the classroom?

Limiting factors within schools

Although the rising stars appear to come from all phases, types of school and a range of socio-economic contexts, common limiting factors in their schools’ culture and organisation are emerging:

- Less confident schools, that are focused on exam outcomes, attendance targets and rigorous behaviour management structures, where young people are lost in the drive for data;

- Schools with highly structured, frequent testing, where young people have too few opportunities to be inspired, to be creative, or to learn in depth;

- Schools with strict ability grouping and differentiation practices, built on assumptions of ability;

- Prescriptive schemes of work that leave little scope for teachers’ creativity, or for young people’s expertise – there is no time for deep learning in a classroom where quantity matters more than mastery;

- Pedagogies that are teacher-focused and controlled, leaving too little scope for young people to become independent researchers, problem solvers or learning leaders;

- Schools that misconstrue presentations of negative learning character as misbehaviour: the window-gazer, who finds the ideas inside her head more interesting but has no chance to share or explore them; the disruptive, who wants to let the teacher know that he is capable of much more challenging stuff but doesn’t know how to say it; the angry or withdrawn, who doesn’t understand and can’t process the work because her learning needs have not been recognised; the passive, unconfident, who finds the classroom crowded and oppressive;

- Schools that have an extended core curriculum at the expense of the creative/expressive arts, design and PE, where young people have little opportunity to grow into disciplined, collaborative, creative learners and critical thinkers, or to have their creative/expressive/physical abilities and talents acknowledged and celebrated.

Why are some students thriving at home?

Teachers are telling anecdotes about the “rising stars” they are noticing and are asking their pupils why they are more engaged and making more progress.

What is striking is the deepening mutual trust and respect which is clear in their voices:

“I am encouraging students to engage with their world, to discover new resources. They are enjoying daily, short skills practices that they self-assess with the help of a simple quiz. They enjoy gaining mastery, rather than marks.”

“I have discovered hidden stars from having personal learning conversations. I was bogged down in a mountain of marking and concerned that only 30% of my students were submitting any work. So I decided to abandon the prescribed written feedback procedure and give each student a two-minute verbal personal moment each week. I didn’t realise how important it was for students to see me, to be called by their name and to feel they mattered to me. I have been really surprised by how able many of them are.”

“I find that quiet students are benefitting from being at home, without the pressures and noise of school. I didn’t realise how capable they are and am wondering why they are not in the top set.”

“I’m in a school where we are expected to maintain the full curriculum and schemes of work. We soon discovered that it was impossible, so my department re-designed the study programme, built on two principles: students can follow their own interests; they should create something – grow it, design it, build it, then teach your teacher and class what you know. We are on hand with advice and we have created a huge bank of resources for them to use, including examples of the department’s special interests and their own creations. Some great experts are emerging – both students and staff!”

Creative writing is a struggle for many young people, who often have a fixed view “I can’t do it.” One Year 5 pupil was very anxious about having to do creative writing tasks at home. “In school, there’s a plan on the board and I can put my hand up when I’m stuck.” Finding it easy to come up with “lots of ideas”, but getting stuck on how to develop them further, he is enjoying sharing his ideas at home and on FaceTime with his friends. “It’s much nicer than at school and I think I am getting much better.”

One-to-one tutorials are building young people’s confidence and respectful relationships with their teachers, who are able to see their capacity. A Year 12 tutor was struck with how powerful the tutorial can be: “It’s fascinating to listen to him. He has great insight and knows more than I do!” Another Year 12 student is appreciating the value of having a trusting and mutually respectful relationship with her tutors. She had a difficult pathway through the GCSE years, excelling in the subjects where she had private one-to-one tuition but unable to achieve her best outcomes in the rest. Now, through daily contact with her tutors, personal advice whenever she wants it, constant collaborative learning opportunities with her peers and with new-found confidence in her capacity, she is totally engaged with her Year 12 studies. “I miss being in school and I certainly miss my friends, but the work is going well. And I am looking forward to going in after half-term for real, live tutorials.”

“At Key Stage 3, introverted students remain mute for the lesson, reluctant to engage or speak but still submit a high standard of work. In contrast, when speaking to these students on a one-to-one basis, they will be forthcoming with how they are feeling. One ‘live’ call a week from their tutor is making a big difference to their progress and their wellbeing. Key Stage 4 and 5 students have adapted exceptionally well. I should mention that they are used to independent learning: they do a lot of reading around their subjects.”

What can we learn for our future practice?

Good friends from the retired headteachers’ community are entertaining each other with tales from the home front. They are discovering that IT is not a mysterious world inhabited by the young but an exciting avenue into following their interests and exploring new places: playing in a huge online orchestra, singing in Gareth Malone’s choir, visiting the theatres, galleries, faraway lands. And they are clearing the loft! An opportunity to throw out unneeded items that must have been useful once, but you have forgotten why – but also to rediscover lost treasures, hidden gems, that deserve to be brought back into the home, polished and put to good use. Perhaps this period of home schooling is our chance to clear out the curriculum and pedagogy loft, to discard what is not useful and to rediscover and polish up the gems of our principles and practice in the light of what young people are telling us.

NACE’s core principles include the statements:

- Providing for more able learners is not about labelling, but about creating a curriculum and learning opportunities which allow all children to flourish.

- Ability is a fluid concept: it can be developed through challenge, opportunity and self-belief.

In its chapter on Teaching for Learning, The Intelligent School (2004) presents a profile of the Learning and Teaching PACT – what the learner and the teacher bring to learning and teaching and, in turn, what they both need for the PACT to have maximum effect. Features of the PACT are visible in the accounts of rising stars, where both learner and teacher bring:

- A sense of self as learner;

- Mutual respect and high expectations;

- Active participation in the learning process;

- Reflection and feedback on learning;

And where the teacher brings:

- Knowledge, enthusiasm, understanding about what is taught and how;

- The ability to select appropriate curriculum and relevant resources;

- A design for teaching and learning fit for purpose;

- An ability to create a rich learning environment.

“Place more emphasis […] on the microlevel of things […] It encourages a culture that is more open and caring […] It requires genuine connection.” – Leading in a Culture of Change (2004)

Chapter 4 of Michael Fullan’s Leading in a Culture of Change is entitled “Relationships, Relationships, Relationships”. Young people are letting their teachers know that personal conversations are enabling their learning. One group of Key Stage 3 students have asked their teachers to stop using PowerPoint presentations, which they feel unable to understand – “But it all makes sense when we talk about it with you.” Learning conversations may be a rediscovered gem in some schools, worth bringing down from the loft of forgotten treasure.

From the same chapter: “When you set a target and ask for big leaps in achievement scores, you start squeezing capacity in a way that gets into preoccupation with tests […] You cut corners in a way that ends up diminishing learning […] I want steady, steady, ever deepening improvement.”

Motivation comes from caring and respect: “tough empathy” in Fullan’s terms. The rising stars are being noticed in a learning environment free from classroom tests and marking. We may need to take a close look at assessment practices in our loft clearance and rediscover the gems of self-assessment, academic tutorials, vivas and reflective discourse.

Can we improve young people’s chances of stardom by considering some fresh thinking, as we prepare for more of them to return to school?

- What will “homework” mean? Can we build on what we are learning about best practice in home schooling?

- How will we inspire (rather than push) young people to high aspirations and outcomes?

- How can we listen better and build respectful, healthier learning relationships?

- Can we design learning for depth and mastery rather than for assessment/testing and quantity?

- How can we open up the curriculum and learning to creativity?

- How can we exemplify and model best learning in our lessons?

- How can we give young people time, resources and personal space to learn how to learn, to become the best they can be?

References and further reading:

- The Intelligent School (Gilchrist, Myers & Reed, 2004)

- Leading in a Culture of Change (Michael Fullan, 2001)

- Engaging Minds (Davis, Sumara & Luce-Kapler, 2008)

- Knowledge and The Future School (Young, Lambert, Roberts & Roberts, 2014)

- Reassessing Ability Grouping (Francis, Taylor & Tereshenko 2020)

This article was originally published in the summer 2020 special edition of NACE Insight, as part of our “lessons from lockdown” series. For access to all past issues, log in to our members’ resource library.

Tags:

confidence

curriculum

identification

independent learning

leadership

lockdown

remote learning

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Matthew Williams,

21 May 2020

|

Dr Matthew Williams, Access Fellow at Jesus College, Oxford, shares his belief in the importance of “confident creativity” as the key to developing sustained effort and a lasting love of learning.

I am a fellow and tutor in politics at Jesus College, Oxford, and I’d like to share some thoughts on how students can be energised to “work harder”. Specifically how do we encourage sustained effort, leading to improved attainment? What follows are reflections on a decade of teaching and schools outreach work at Oxford and Reading Universities. There is a mixture of theory here, but readers should be warned there will also be big dollops of unscientifically personal recall.

As an undergraduate student of politics at the University of Bristol, the most significant learning experience came during seminars on the British Labour Party. At first, I was fairly indifferent on the subject, but the seminars entailed a mixture of traditional essay-based research and more flashy simulation-based learning. On the latter, we had a Cabinet meeting in our seminar with each of us playing real characters. I was Jim Callaghan, and I had to prepare Cabinet papers, work out strategy and tactics in order to win a fight with, in particular, Tony Benn!

The experience brought everything to life. The theoretical and practical came together, and I have to this day never forgotten the specifics of that fight in late 1976. On reflection, the primary effect of the simulation was the transformation of the subject matter from work into study. Studying is not work in the sense of being performed for someone or something else’s benefit. Instead, studying is intrinsically pleasurable. Whilst many students are motivated by long-term payoff (career prospects, reputation, power etc) many, like me, see more immediate feedback. This particular teaching style transformed the 9am walk to lectures from a reluctant trudge to an enthusiastic commute. It was revelatory.

Demystifying the means of achieving distinction

Ever since those seminars I have aspired in my personal and professional life to transform work into study. The key ingredient used by the seminar tutor was positive motivation. He made clear his interest was in us and our ideas, rather than our performance in the exam and the reputation of the university. As such, he did not want us to regurgitate the literature, rather he wanted us to know the literature so we could analyse it critically whilst presenting our own original contributions.

This was liberating. All of sudden the most complex elements of social democratic ideology and post-industrial economics were not prohibitively intimidating; they were required reading for anyone wishing to have their voice heard. In this process, we had to acknowledge we could contribute to a debate despite our relative academic inexperience. The tutor was clear: good ideas are not the monopoly of tenured professors. If we wanted to, we were perfectly capable of contributing original theoretical insights and empirical discoveries. To achieve the distinction of a first class degree our work had to be creative and, crucially, the tutor made clear we were all capable of distinction if we wanted it.

This teaching style resonated with me because it demystified the means of achieving distinction. Previously, I had assumed distinction was a matter of talent, intelligence and luck – none of which I felt much graced with. Subsequently, I realised distinction meant creativity, and creativity needed energy and self-confidence.

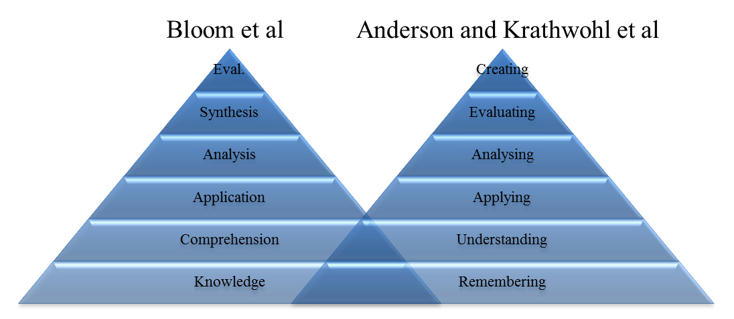

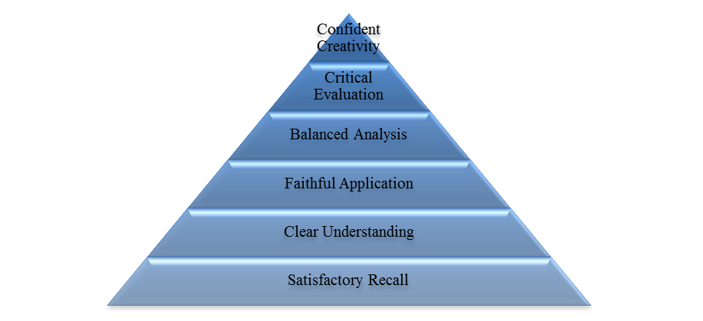

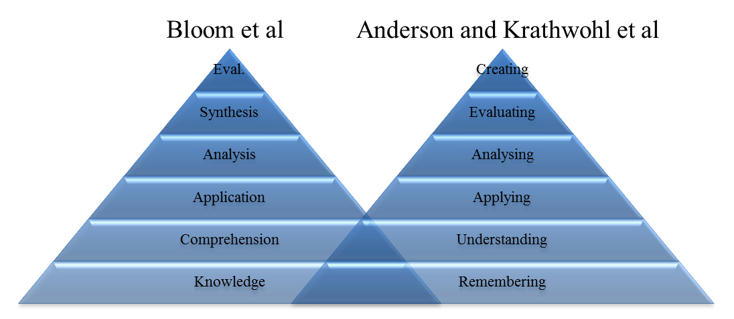

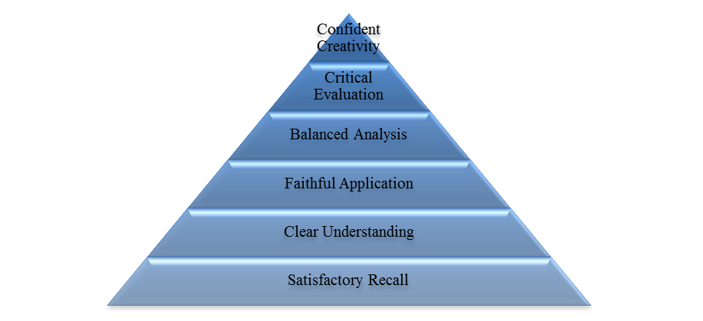

Understanding the importance of “confident creativity”

“Confident creativity” is not my first teaching philosophy. For a job application in 2012 I proposed a similar philosophy focused on positive motivation and confident application of skills. Whilst this is seemingly the same philosophy, the older version was predicated on teaching as the transmission of knowledge, where now I see teaching more as developing and nurturing key skills. The transmission model prioritised interesting learning materials as the fundamental variable; whilst I still consider the materials to be important, they are secondary to the students’ nurtured development of complex skills. When students internalise the skills of processing complex information, they will find interest in practically all relevant materials, without the need for unrepresentatively “sexy” content. Even a 1970s Cabinet meeting can become enthralling!