Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Matthew Williams,

21 May 2020

|

Dr Matthew Williams, Access Fellow at Jesus College, Oxford, shares his belief in the importance of “confident creativity” as the key to developing sustained effort and a lasting love of learning.

I am a fellow and tutor in politics at Jesus College, Oxford, and I’d like to share some thoughts on how students can be energised to “work harder”. Specifically how do we encourage sustained effort, leading to improved attainment? What follows are reflections on a decade of teaching and schools outreach work at Oxford and Reading Universities. There is a mixture of theory here, but readers should be warned there will also be big dollops of unscientifically personal recall.

As an undergraduate student of politics at the University of Bristol, the most significant learning experience came during seminars on the British Labour Party. At first, I was fairly indifferent on the subject, but the seminars entailed a mixture of traditional essay-based research and more flashy simulation-based learning. On the latter, we had a Cabinet meeting in our seminar with each of us playing real characters. I was Jim Callaghan, and I had to prepare Cabinet papers, work out strategy and tactics in order to win a fight with, in particular, Tony Benn!

The experience brought everything to life. The theoretical and practical came together, and I have to this day never forgotten the specifics of that fight in late 1976. On reflection, the primary effect of the simulation was the transformation of the subject matter from work into study. Studying is not work in the sense of being performed for someone or something else’s benefit. Instead, studying is intrinsically pleasurable. Whilst many students are motivated by long-term payoff (career prospects, reputation, power etc) many, like me, see more immediate feedback. This particular teaching style transformed the 9am walk to lectures from a reluctant trudge to an enthusiastic commute. It was revelatory.

Demystifying the means of achieving distinction

Ever since those seminars I have aspired in my personal and professional life to transform work into study. The key ingredient used by the seminar tutor was positive motivation. He made clear his interest was in us and our ideas, rather than our performance in the exam and the reputation of the university. As such, he did not want us to regurgitate the literature, rather he wanted us to know the literature so we could analyse it critically whilst presenting our own original contributions.

This was liberating. All of sudden the most complex elements of social democratic ideology and post-industrial economics were not prohibitively intimidating; they were required reading for anyone wishing to have their voice heard. In this process, we had to acknowledge we could contribute to a debate despite our relative academic inexperience. The tutor was clear: good ideas are not the monopoly of tenured professors. If we wanted to, we were perfectly capable of contributing original theoretical insights and empirical discoveries. To achieve the distinction of a first class degree our work had to be creative and, crucially, the tutor made clear we were all capable of distinction if we wanted it.

This teaching style resonated with me because it demystified the means of achieving distinction. Previously, I had assumed distinction was a matter of talent, intelligence and luck – none of which I felt much graced with. Subsequently, I realised distinction meant creativity, and creativity needed energy and self-confidence.

Understanding the importance of “confident creativity”

“Confident creativity” is not my first teaching philosophy. For a job application in 2012 I proposed a similar philosophy focused on positive motivation and confident application of skills. Whilst this is seemingly the same philosophy, the older version was predicated on teaching as the transmission of knowledge, where now I see teaching more as developing and nurturing key skills. The transmission model prioritised interesting learning materials as the fundamental variable; whilst I still consider the materials to be important, they are secondary to the students’ nurtured development of complex skills. When students internalise the skills of processing complex information, they will find interest in practically all relevant materials, without the need for unrepresentatively “sexy” content. Even a 1970s Cabinet meeting can become enthralling!

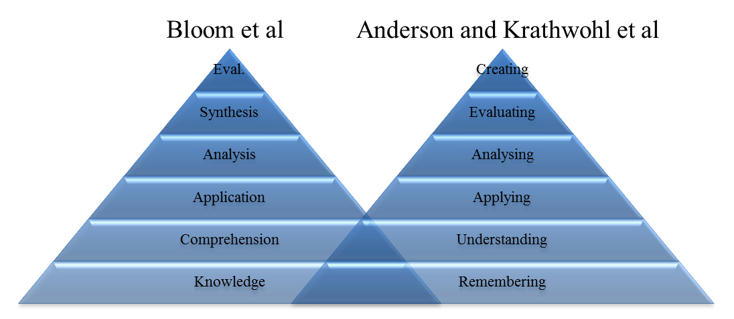

The key change in my teaching philosophy has been the realisation that motivating students should encourage a sense of independent intellectual development. This change in emphasis can be represented as a synthesis of two learning outcome hierarchies, proposed by Bloom et al (left pyramid) and Anderson & Krathwohl et al (right pyramid).

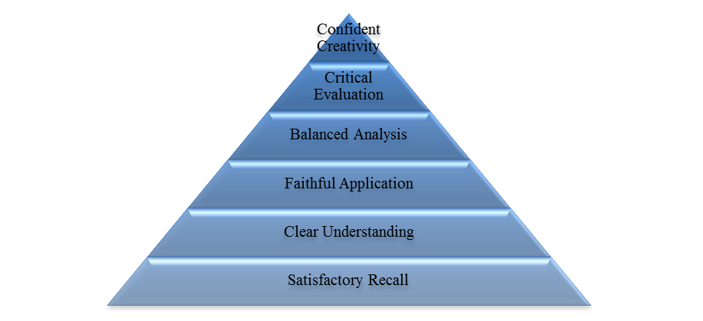

I propose a synthesis of these taxonomies, fleshed out with qualifying adjectives:

Including qualifying adjectives in Anderson & Krathwohl et al’s hierarchy allows us to assess the learning objectives in greater detail, with clearer observable implications. Adding an extra level of nuance to the concepts enriches their meaning, without losing the parsimony and clarity which are such key strengths of the original taxonomy. The addition of adjectives could be criticised as creating needless tautologies – if, for instance, we assume confidence is a necessary condition of creativity. However, creativity can be achieved without confidence if it is accidental and the student is unaware of the merits of their creativity. We need to aim for confident creativity because it is significantly more sustainable and transferable for a student to create in confidence than to be creative by accident or with heavy-handed guidance.

Transferring this approach to different contexts

Critical reflexivity is a very personal journey, and the results of my personal reflections may not be transferable. Even the phrase “teaching philosophy” connotes a sense of philosophy as retroactive rationalisation of one’s own perspective, as opposed to the analytic use of the term as a clear, open and rigorous system of thought. As Nancy Chism states, somewhat ironically, “One of the hallmarks of a philosophy of teaching statement is its individuality.” Whilst a teaching philosophy is developed through self-reflection, it requires self-awareness before it can be applied to others. Notably, teachers are somewhat unusual in their relationship with knowledge. They relish the acquisition of knowledge as an intrinsic good, where motivation to learn is rarely absent and the desire to contribute is second nature.

But what is good for the goose is not necessarily good for the gander. For many students school and college is first and foremost about acquiring qualifications, and therefore simply an instrument for career advancement. As such, not all students want to achieve distinction, nor see the value in risking creative contributions when a less resistant path exists. For such students there is a risk that emphasis on creativity will alienate them from the subject and the teacher. Furthermore, the development of my teaching philosophy has primarily taken place at an elite university, where boundary-pushing and intellectual confidence is far less risk-laden than in other contexts. The unflinchingly liberal environment at Oxford ascribes considerable value to intellectual creativity, perhaps at the expense of consolidation. Yet there is little utility in a teaching philosophy that is contingent on where and for whom it applies.

Nevertheless, these concerns are surmountable. Yes, academics perhaps have a gilded view of knowledge, but only because they have internalised the skills of contributing knowledge to the point where it has become (for the most part) a pleasure. It is incumbent on academics to encourage students towards a similar relationship with the world. Whilst not all students will want or feel able to contribute genuine insights, “confident creativity” is the apex of the pyramid and there are other levels of learning available to differentiate between learners. The ambition should be to encourage confident creativity, but “critical evaluation” or “balanced analysis” will be satisfactory outcomes for many students. Learners should not be forced to fit a teaching style that alienates them and a degree of differentiation between students will be required with the proviso that “confident creativity” is unambiguously the preferred goal and should be encouraged as far as possible.

Ultimately, the point of education is to equip individuals with the skills to speak for themselves. This is best achieved when we mix up teaching styles, and jolt work into study.

References

- Anderson, L.W., Krathwohl, D.R., Airasian, P.W., Cruikshank, K.A., Mayer, R.E., Pintrich, P.R., Raths, J., & Wittrock, M.C. (eds) (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing. (New York: Addison Wesley Longman Inc).

- Bloom, B.S., Engelhart, M.D., Furst, E.J., Hill, W.H., & Krathwohl, D.R. (eds) (1956) Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals – Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain. (London, WI: Longmans, Green & Co Ltd).

- Chism, N. V. N. (1998) “Developing a Philosophy of Teaching Statement.” in Essays on Teaching Excellence 9(3) (Athens GA: Professional and Organizational Development Network in Higher Education).

- Pratt, D.D., & Collins, J.B. (2000) ‘The teaching perspectives inventory: Developing and testing an instrument to assess teaching perspectives’ Proceeding of the 41st Adult Education Research Conference.

About the author

Dr Matthew Williams is Access Fellow at Jesus College, University of Oxford, where he teaches and conducts research in the field of political studies. Known as “the Welsh College”, Jesus College has a long history of working with schools in Wales and has recently taken on responsibility for delivering the university’s outreach and access programmes across all regions of Wales. Read more.

Live webinar: “Developing sustained effort in able learners”

On 2 July Dr Williams is leading a free webinar for NACE members in Wales, exploring approaches to developing confident creativity and motivating learners to be ambitious for themselves. This is part of our current series supporting curriculum development in Wales. Find out more and book your place.

Tags:

aspirations

confidence

CPD

creativity

independent learning

Oxbridge

Oxford

pedagogy

Wales

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Catherine Metcalf,

09 October 2019

|

Cathy Metcalf, Year 5 teacher and expressive arts lead at St Mary's RC Primary School, shares four approaches to help learners move beyond the search for a single right answer.

For many of our more able learners, much of their education is spent seeking (and usually finding) answers. Correct answers. They are the children in our class who ‘know’ they have the answer we are looking for, and frequently the learners who struggle when they get an answer wrong. But how do these learners cope when there is no ‘right’ answer? When everyone’s ideas and opinions are valued and acceptable, and right and wrong are no longer the outcomes or intentions of the lesson?

Element 3c of the NACE Challenge Framework reminds us of our responsibility to consider “social and emotional support” as well as academic provision for the more able. Similarly, the updated education inspection framework (EIF) calls for schools to develop “pupils’ character… so that they reflect wisely, learn eagerly, behave with integrity and cooperate consistently well” and “pupils’ confidence, resilience and knowledge so that they can keep themselves mentally healthy”. In Wales too, wellbeing has a significantly raised profile in the context of ongoing curriculum reform.

Learners who are not used to the feeling of struggle and failure are likely to crumble when faced with a task or approach that does not entail a straightforward correct answer. As practitioners, we have a responsibility to ensure that our more able learners are regularly exposed to a high-enough level of challenge to experience the feeling of struggle, in an environment where they feel part of a supportive learning community.

In my ‘other life’ (beyond teaching) I have worked as a musical director in theatre for nearly 15 years, and I feel that the expressive arts provide so many opportunities for this kind of development. I am always looking for ways to explore and use the arts in my pedagogical approach, and have found the following approaches to be particularly successful for more able learners:

1. Draw on creative role models to develop growth mindset

Carol Dweck’s theory of growth mindset is important to helping learners understand the benefits of ‘staying with’ a task or problem, even when it feels beyond their ability – and here, there is much to be learned from the world of expressive arts.

Many artists and musicians spend weeks, months, even years perfecting a work. Even the process of rehearsing for a performance (be it a school concert, instrumental examination or West End production) requires dedication and resilience, calling for repetition after repetition to ensure consistency.

For learners it can be powerful to take inspiration from an artist or other celebrity and to understand how they approach their craft. The NACE Essentials guide to learning mindset suggests encouraging learners to “research individuals they admire who have achieved something great and explore what these people have in common.”

In my school, figures such as Walt Disney and J. K. Rowling are year-group models, and pupils learn about how they have created their masterpieces through teamwork, setbacks and extensive editing. Developing a growth mindset permeates our whole school culture and reinforces the idea that “the most certain way to succeed is always to try just one more time” (Thomas Edison).

2. Set creative open-ended tasks

The guidance for more able learners from the regional consortia within which I work suggests “setting creative open-ended tasks” within our everyday practice. I recently used a task which involved playing short excerpts of music and asking children (and staff) to choose the colour they felt the music was describing.

Of course, with this type of task there is no ‘right’ answer, yet the lesson serves many purposes: to encourage reasoning and justification for any answer, to develop child talk in a low-stake environment, and as an introduction to the technical vocabulary required for describing music.

It was particularly interesting to note how many of my more able learners were fixated upon ‘Yes, but who is right Miss?’ and I am already planning further activities using paintings, sculpture and digital art to try and change this mindset.

3. Provide regular mental workouts

In its recent thematic review of provision for more able learners, Estyn recognises a problem in many schools of simply setting more work in terms of quantity, rather than extensions which require deeper thinking.

I try to provide my class with opportunities to think deeply about their academic work, but also to think deeply in an altogether more abstract, creative way. The use of ‘thunk’ questions and ‘cognitive wobble’ are particularly strong ways of encouraging learners to question their own perceptions of the world, and even to challenge information that is presented to them by teachers and parents.

Some of my favourite ‘thunks’ are excellent warm-ups for art, drama and literacy lessons… e.g. If I drop a bucket of paint on a canvas, is it art? What if I drop the bucket deliberately? What colour is Tuesday? If I compose a piece of music, but it is never played, is it still music?

Character studies during drama or literacy lessons also provide opportunities for ‘cognitive wobble’ – the result of conflicting information clashing when we need to form an opinion about something. e.g. We know thieves are villains, and yet Robin Hood is a hero...

My class last year also took part in a project with a visiting neurologist, who taught the pupils about the brain, and how it works in the same way as any other well-exercised muscle. They learnt about different parts of the brain and how it functions, and many were able to make links with the ongoing work we had done on mindset.

4. Challenge parents to change their perspectives

Finally, I am reminded of a conversation with a parent who had been flicking through a maths book before a parent-teacher consultation. The parent commented on the number of mistakes in the book and expressed concern over their child’s lack of mathematical understanding. The child in question was, in fact, a strong mathematician who really thrived when challenged and was learning to articulate her mistakes and what she had learnt from them.

If we want to reframe the concept of success for our learners, we also need to challenge the perception of ‘right’ answers held by parents – which in many cases is passed on to their children. Ensuring that parents are well informed of the learning culture in a school, particularly that of mindset and deep learning/challenge is crucial in supporting this change.

We have recently introduced Individualised Achievement Plans for our most able learners, which involve a target-/project-setting meeting between learner, teacher and parent, and already we are seeing the benefits of parents’ support when more open-ended tasks are introduced and continued at home.

I was particularly struck by a comment in the NACE Essentials guide to learning mindset: “the risk with more able learners can be that teachers do not sufficiently reward effort, due to success being perceived as a ‘given’ [… A]ll learners need ‘process praise’ to build or reinforce that all-important growth mindset.” This is of course true, and not just of learners at school age. We all need to feel as though our efforts, whether at work or elsewhere, are appreciated, and we are all likely to perform better when praised.

For our young learners, receiving support, praise and encouragement not only at school but also at home can have a huge impact. Engaging with parents to ensure a consistent approach is key.

I recently read an NCETM article titled “The answer is only the beginning”. It seems to me that the more we are able to instil this mindset in our more able learners, the better we equip them for whatever challenges they may face, both academically and throughout their lives.

References and further reading

· Healthy and happy – school impact on pupils’ health and wellbeing (Estyn, 2019)

· How best to challenge and nurture more able and talented pupils: Key stages 2 to 4 (Estyn, 2018)

· Regional Strategy and Guidance for More Able Learners (Education Achievement Services for South Wales, 2018)

· NACE Essentials: Using mindset theory to drive success (NACE, 2018; login required)

· The Learning Challenge (James Nottingham, 2017)

· The Little Book of Thunks (Ian Gilbert, 2007)

NACE member offers: for details of current discounts available from our partner organisations, including education publishers such as Crown House, Hodder, SAGE, Rising Stars and Routledge, log in to our members’ site.

Tags:

creativity

Estyn

mindset

neuroscience

Ofsted

parents and carers

resilience

Wales

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Bill Lucas,

10 July 2019

|

Professor Bill Lucas, Director of the Centre for Real-World Learning at the University of Winchester, shares five key steps for schools and practitioners seeking to embed creativity in teaching and learning.

It’s 20 years since the landmark National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education report All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education was published. The report offered a simple definition of creativity: “Imaginative activity fashioned so as to produce outcomes that are both original and of value.” Two decades on and we are much clearer about the cultural and pedagogical changes necessary for creativity to be embedded in schools, so much so that PISA has made creative thinking the subject of a new test in 2021.

Closer to home, Wales is launching a new curriculum that gives a central place to creativity and the new Ofsted framework comes into force this year. Not traditionally associated with creativity, Ofsted’s encouragement to schools to think more widely about curriculum and to document their intent, implementation and impact is an opportunity to rethink the role of creativity in schools.

In this context, here are five key steps to consider:

1. Understand what creativity is

You might like to start by familiarising yourself with our model of creativity and its five habits:

Bill Lucas, Guy Claxton and Ellen Spencer, ( OECD, 2013) 2. Review your classroom culture

Look at these 10 statements and ask yourself how much your classroom encourages these:

- Learning is almost always framed by engaging questions which have no one right answer.

- There is space for activities that are curious, authentic, extended in length, sometimes beyond school, collaborative and reflective.

- There is opportunity for play and experimentation.

- There is opportunity for generative thought, where ideas are greeted openly.

- There is opportunity for critical reflection in a supportive environment.

- There is respect for difference and the creativity of others.

- Creative processes are visible and valued.

- Students are actively engaged, as co-designers.

- A range of assessment practices are integrated within teaching.

- Space is left for the unexpected.

10 of 10? Go to the top of the class! 5 out of 10? Encouraging. Just 2 or 3 out of 10? You’re out of the starting blocks but have a way to go yet…

3. Use signature pedagogies to embed creativity

A signature pedagogy is a teaching method which is explicitly connected to the desired outcome of any lesson. So if you want curious students you might choose problem-based learning. If you want pupils to be critically reflective, then philosophy for children might be a helpful approach. Or if persistence was your goal, then any number of growth mindset type approaches such as changing learner talk from “can’t” to “can’t yet” might work. Other useful methods include the use of case studies, deep questioning, authentic tasks, a focus on the design process, enquiry-led teaching and deliberate practice.

4. Use split screen teaching to embed creativity in every subject

Split screen teaching, pioneered by my colleague Guy Claxton, invites teachers to describe two worlds, the disciplinary subject matter of their lesson and the aspect of creativity on which they are also focusing. Let’s say you were introducing a science activity to understand the properties of acids and bases and then pupils were to prepare a short demonstration for other pupils, who would in turn offer feedback to their peers on the effectiveness of their explanations. Or in a history lesson, students might be looking at the causes of the First World War at the same time as they are exploring aspects of critical thinking such as the use of primary sources of evidence.

In the imaginary split screen of the lesson and its objectives a teacher would take care to explain to the class that both the chemistry (acids and bases) and the creative thinking (giving and receiving feedback) objectives were equally important.

Split screen teaching reminds us of the importance of embedding creative habits in the context of a subject. For example: history + critical reflection; scientific enquiry + appropriate cooperation; writing an argument in English + challenging assumptions.

5. Use thinking routines

The use of visible thinking routines, well-documented by Harvard University’s Project Zero, is an invaluable way of moving from knowledge to creative habits. A routine such as Think-Puzzle-Explore embeds inquisitiveness, while Think-Pair-Share-Think provides routine opportunities for challenging assumptions and giving and receiving feedback.

Later this year the Durham Commission will make recommendations for ways in which school leaders and teachers can be supported in England. Now is the time to get determined and creative about giving all children the chance to develop their creativity at school.

Professor Bill Lucas is director of the Centre for Real-World Learning at the University of Winchester and co-chair of the strategic advisory group for the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA)'s 2021 test of creative thinking. He is the author of many books on creativity and learning including, with Ellen Spencer, Teaching Creative Thinking: Developing learners who generate ideas and can think critically. He tweets at @LucasLearn

Tags:

creativity

curriculum

pedagogy

PISA

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Elizabeth Allen CBE,

10 June 2019

Updated: 05 August 2019

|

Far from being “soft” or “easy” options, the creative arts, design and physical education have an essential part to play in delivering a broad, challenging and opportunity-rich curriculum. NACE trustee Liz Allen CBE explores the current status of these subjects in UK schools, and shares next steps for school leaders…

“In whatever way you construct your list of 21st century skills, you will always come across creativity – creating new value… bringing together the processes of creating, of making, of bringing into being and formulating and looking for outcomes that are fresh and original… This is all about imagination, inquisitiveness, collaboration, self-discipline.” - Andreas Schleicher, Director for Education and Skills and Special Adviser on Education Policy, OECD

Why prioritise creative arts, design and physical education?

If one of the purposes of education is to prepare young people for their working lives, we need to ensure they are equipped with the creative, imaginative, problem-solving skills that will enhance their economic future. The growing opportunities in creative businesses, science, technology and the media offer them a bright future: those who have experienced a rich, creative curriculum will have a head start and their quality of life will be enhanced in many ways.

Social impact

The social value of creative arts and design education is widely evidenced. Schools with a strong academic and enrichment offer in the arts, design technology and physical education create a culture of citizenship, service and tolerance. Young people who engage in creative activities are more likely to feel socially confident, to take on roles of responsibility and to be active members of their community.

Most significantly, there is a growing body of evidence that participation can improve social mobility. The Cultural Learning Alliance (CLA)’s 2018 briefing on arts in schools found that students from low-income backgrounds are three times more likely to get a degree. They benefit most from access to their cultural heritage and the opportunity to develop their creative thinking and the perseverance and self-discipline to succeed.

Cross-curricular benefits

The educational value goes beyond the creative arts, DT and PE curriculum. Studying these subjects improves young people’s cognitive abilities and enhances their performance in English and mathematics, especially for young people from low-income backgrounds. The CLA paper argues that “they are as essential as literacy and numeracy in equipping children with the skills for life and the creativity to contribute to the building of a successful nation.”

Wellbeing and personal development

The personal value of creative arts, design and PE may have been grossly underestimated. It is possible there is a causal link between the decline in the arts, technology and PE curriculum and enrichment provision and the worrying rise in young people’s mental health issues, feelings of low self-esteem and lack of self-regulation.

There is no doubt that participation in the creative arts, design and sport make us happier and healthier. The Time To Listen research articulates the value that both young people and their teachers place on their relationships: “…teachers approached students as ‘artists’… (working) to encourage intellectual and disciplinary skills development… to take risks, to be responsible for deadlines… to engage in critical interpretation of their own and others’ work.”

The high levels of trust and respect between teachers and students allow young people to build both the empathy and resilience to succeed in collaborative and challenging environments. The experience of being part of a team – preparing for a production, performance, competition, exhibition – may not eliminate the pressures young people face but it can give them a strong sense of self-worth and the socio-emotional confidence and skills to overcome them and thrive.

The decline in arts, design and PE provision in our schools

Despite all the well-documented evidence, arts and design provision continues to decline; the CLA paper cites a 2017 ASCL/BBC survey which found 90% of school leaders had reduced arts provision in their schools over the past two years. A number of factors are pushing them further out of reach:

Misguided perceptions

For many years, the prevailing view in the state sector has been that the arts, design and sport are a pleasant diversion from academic rigour for the more able and good choices for students who are less academic and more practically inclined – all far from the truth, as the independent sector has demonstrated.

To excel in music, art, dance, design technology or sport, young people develop high levels of critical analysis and creative thinking, the rigour of listening, sharing expertise and collaborating, the self-discipline to practise and persevere. Far from being “soft” options, they help to build the character and competencies that lead to success in the core and foundation subjects.

School performance measures

Recent national strategies and their accountability systems have had unintended consequences, making it increasingly difficult for subjects to survive if they don’t count in performance measures. I recall the introduction of the EBacc as a concept, even before it became a formal measure: many school leaders rushed to re-configure their GCSE option choices, anxious for students to choose subjects that would count the most.

The introduction of new GCSE specifications prompted a move in many schools to start GCSE courses in Year 9; the opportunity for young people to study creative subjects in depth were drastically reduced and it became increasingly difficult for schools to sustain specialist teaching. Primary schools faced similar challenges from the change in Key Stage 2 performance measures.

Financial pressures

Significant ongoing reductions in school funding make curriculum design and delivery increasingly challenging. The fear is that, once the specialist teaching and resources are lost it will be hard to reinstate them.

Reasons to be optimistic

There are the early signs of positive change that should fuel our optimism.

The Russell Group’s recent decision to remove its list of “facilitating subjects” for A-level choices is a welcome start.

The new Ofsted inspection framework (2019), “will move Ofsted’s focus away from headline data to look at how schools are achieving these results and whether they are offering a curriculum that is broad, rich and deep… Those who are bold and ambitious and run their schools with integrity will be rewarded.” (Amanda Spielman, press release)

And – as we see from our own community of NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools – there are many examples of schools which offer a broad, rich and deep curriculum and which show integrity by putting the life chances of their students first when making curriculum and staffing decisions. As a consequence, their students and staff thrive in a school that is alive with creative energy.

Case study: Greenbank High School

At Greenbank High School, teachers’ deep subject knowledge and expert questioning lead to high levels of discourse: students are articulate, critical, creative thinkers and confident, resilient learners. The broad, rich curriculum runs from Year 7 through to 11, with opportunities for students to specialise (e.g. in languages, the arts) from Year 9.

Strong collaborative working relationships with primary, FE and HE providers and excellent in-house careers advice and guidance create a culture of deep learning and high aspiration. The school buzzes with activity: students enjoy the range of academic, physical and creative challenges and the leadership opportunities they bring; they are socially aware and active in supporting each other, both academically and emotionally and see themselves as global citizens.

Case study: Oaksey C of E Primary School

At Oaksey C of E Primary School pupils experience a rich, deep subject curriculum aimed at developing “lively, enquiring minds with the ability to question and argue rationally. We aim to enable our children to be well motivated both mentally and physically for success in the wider world.” As well as academic rigour, there is a focus on values: “valuing human achievement and aspirations; developing spirituality, creativity and aesthetic awareness; finding pleasure in learning and success.”

IT and computing have a high profile: “to enrich and extend learning; to find, check and share information; to create presentations and analyse data; to use IT in real contexts and appreciate e-safety and global applications.” The school grounds are a rich learning environment, with spaces for performance, meditation and reflection designed and constructed by the pupils, as well as places for horticulture and play. Music provision is strong: a specialist part-time teacher and a richly equipped music room (funded by the children’s fund-raising efforts in the community), give every child the opportunity to learn and perform.

What steps can school leaders take?

Taking courage from the Russell Group’s decision, Ofsted’s messaging and the examples of schools which have succeeded in maintaining a flourishing and broad curriculum, school leaders can consider the following:

- Recognise and celebrate the value of creativity and critical thinking across the curriculum.

- See the creative subjects, PE and design technology as essential to the development of high cognitive performance, self-discipline and collaborative practice, well-deserving of their place in the curriculum.

- Employ specialist teachers and encourage them to engage with professional organisations and the creative industries, so they can continue to see themselves as artists.

- Be adventurous with Pupil Premium funding, to make cultural and creative learning opportunities accessible.

- Manage teachers’ workload so they can focus on rich extracurricular provision. Value and acknowledge the impact enrichment makes on young people’s life chances.

- Engage with national champions in the arts and creative industries. Artsmark, Youth Sports Trust, DATA, the RSC, Get Creative (BBC Arts), the Cultural Learning Alliance and local organisations are among many who can give advice and guidance.

“We owe it to future generations to ensure they experience an education that offers them the whole of life and culture: head, heart and soul.” – Cultural Learning Alliance

Which of the steps above has your school already taken? What would you add to this list? Share your views: communications@nace.co.uk

References:

- Cultural Learning Alliance, Briefing Paper No. 4 2018: “The Arts in Schools”

- Royal Shakespeare Company, Tate, University of Nottingham 2018: “Time to Listen”

- PTI, Children and The Arts 2018: “The Creative, Arts and Design Technology Subjects in Schools”

- Ofsted and HMCI commentary September 2018: “Curriculum and the New Inspection Framework”

- House of Commons, Digital, Culture, Media and Sport Committee 2019: “Changing Lives: The Social Impact of Participation in Culture and Sport”

Tags:

arts

creativity

curriculum

design

enrichment

personal development

physical education

sports

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Matthew Williams,

15 April 2019

Updated: 07 August 2019

|

What are Oxbridge admissions tutors really trying to assess during the famously gruelling interview process? Dr Matt Williams, Access Fellow at Jesus College Oxford, shares “four Cs” used to gauge candidates’ suitability for a much sought-after place.

Oxbridge interviews have taken on near-mythic status as painful reckonings. The way they are sometimes described, a trial by ordeal sounds more appealing.

I used to think as much, before I became an interviewer at Oxford. I’ve worked on politics admissions for several colleges for years now. And “work” truly is the verb here. Admissions tutors and officers at Oxford and Cambridge work very hard over months to ensure they choose the best applicants, and do so fairly. It’s honestly heartening to see how committed tutors are.

It is not even remotely in our interests to put candidates under emotional strain. So a mythic sense of interviews as tests of psychological resilience is nonsense. At Oxford and Cambridge we invite prospective students to come and stay in our colleges, eat in our dining halls and chat with our students and staff. As you’d hope from any professional job interview, the process is friendly, transparent and focused on encouraging the best performances from candidates. Below I’ve outlined a few concrete ideas as to what we are looking for, and how students can prepare.

In the interviews we tend to scribble down notes as the candidate is talking. But what exactly are we recording? What makes for good, mediocre and bad performances at interview? I record lots of data during interviews, which can be collated under four Cs. These help us gauge, accurately, a candidate’s academic ability and potential. This ultimately, is all we are testing at interview…

1. Communication

Candidates do not need to be self-confident and comfortable in expressing their ideas. Our successful candidates are mostly just normal people, with the sort of self-effacing humility you’d expect from a randomly selected stranger. As such, candidates should not be put off by cock-of-the-walk types who seem instantly at ease in our ancient surroundings.

We are not judging candidates by their ease of manner, but we do judge candidates by their ability to communicate. Meaning that candidates need to be able and willing to share their thinking as clearly as possible. Even if a candidate nervously glances at the floor and speaks softly, provided they answer our questions and help us understand their views they will be performing well.

More specifically, we are seeking answers to the questions we pose. There may not be a single answer, but it is not terribly helpful if students try to wriggle out of responding to us. As an example, the following question doesn’t have one correct (or even any correct) response:

“Can animals be said to have rights?”

Candidates need to avoid the temptation of saying either that the question is unanswerable, or sitting on the fence. Such responses are, to be blunt, intellectually lazy. We commonly have candidates “challenging the terms of the question” and thereby not answering the question at all. That is easy. Anyone can do that. Far harder is sticking your neck out and offering a solution, however tentative, to a very complex puzzle.

That said, we’re not expecting candidates to alight on their preferred solution immediately. So candidates should “show their working” and talk through their ideas as they coalesce into a solution. They can challenge aspects of the question and enquire about the wording. It may take the whole interview to come up with an answer, but at least an answer of sorts is being proposed.

2. Critical thinking

The question as to whether animals have rights is contestable. We will challenge any answer a candidate offers to see how they can defend their position. We are not expecting the candidate to drop their resolve and agree with us, but nor should they cohere rigidly to their position if it is clearly flawed. The important point is that candidates are open-minded to the possibility of other, perhaps better, solutions to the puzzle at hand, and a willingness to critique their own thinking.

Often candidates feel that they have done badly when they face critical questioning. Far from it. This is normal and reflects the fact that they have answered the question and given us (the interviewers) something to explore further.

3 and 4. Coherence and Creativity in argumentation

When posing critical questions we may encourage the candidate to identify incoherences in their case. Let’s say they argue that dogs have rights, but racing hounds do not. This could be a category error and we might ask whether they meant to say that all dogs except racing hounds have rights, or if they have made a critical misstep in the case.

Again, having a point of incoherence identified is not a bad sign. What matters is how the candidate responds. If they fail to recognise or resolve a true incoherence, that could suggest an inability to self-critically evaluate an argument.

Creativity, meanwhile, is something of an X-factor. We’re not expecting utterly original thinking in response to our intractable intellectual puzzles. But we do appreciate a willingness not to simply parrot ideas from A-level, or from the press. We appreciate a nascent (but not fully formed) capacity in a candidate to stand on their own intellectual feet.

This is where candidates can (but don’t have to) draw on wider reading or other academic experiences they have had. A lot of candidates are keen to show off what they know, but we’re testing how they think. So, we don’t want long quotes from highfalutin sources, per se; we want the candidates to come up with their own ideas, even if those ideas are half-formed and tentatively expressed.

The bottom line is that we are not looking for perfection, or else there would be little point in seeking to educate the candidates. We’re looking for potential, and it is often raw potential. Therefore willingness, motivation and enthusiasm all play a big part in the four Cs as well.

Tags:

access

aspirations

CEIAG

creativity

critical thinking

higher education

myths and misconceptions

Oxbridge

Oxford

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Alison Pateman,

10 October 2018

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

Earlier this year, NACE member and Challenge Award holder The Broxbourne School was named one of nine schools selected to lead regional language hubs across England, supporting the new Centre of Excellence for Modern Languages. In this blog post, MFL teacher Alison Pateman shares some of the school’s keys to success in promoting the study of and high attainment in modern languages.

1. Make pupils secure… but keep them on their toes!

At The Broxbourne School we achieve this by combining routine with new elements. Our learners know their teacher will begin a new unit by teaching them the necessary vocabulary and grammar and allowing them to write it down in their books. But exactly how the new language will be presented, practised and consolidated is very varied, so they don’t know what to expect next. All our MFL teachers use a mixture of their own techniques and games, in-house-made SMART Notebook files, PowerPoints and worksheets, alongside engaging materials we have on subscription. Songs are fun and a great way to make words stick, while puzzle-making programmes like Tarsia challenge learners think that bit harder, again aiding memory.

2. Encourage learners to be creative

There are endless ways to present, practise and explore languages. Our Year 7 learners produced some wonderful pipe cleaner bugs to practise present tense verb forms. Old kitchen roll cardboard interiors are another good prop – challenge learners to move rings of paper independently of each ring to manipulate language into sentences. The origami paper finger game lends itself to all sorts of language activities. Equally, learners enjoy being creative with scenarios – for example, the Year 8 pupil who wrote her German homework as a series of social media posts, or those who wrote about the weather as a cartoon strip. Meanwhile Year 8 French pupils enjoyed playing a “blame game” to practise all forms of the perfect tense.

3. Celebrate languages outside the classroom

Last year saw our first ever MFL House Quiz, in which learners faced rounds testing their linguistic and cultural knowledge of the countries where our offered languages are spoken. We always celebrate the European Day of Languages (EDL), when all form tutors promote the importance of language learning – for example by taking the register with responses in a foreign language and wearing badges to show which languages they speak. Last year learners looked around the school for EDL posters with greetings in 10 different languages, competing for a prize if they could work out which was which.

4. Grab a slice of the action on PSHE days

Languages are a part of the autumn term Year 8 PSHE day when all learners spend 30 minutes learning an entirely new language, mostly offered by teachers who normally teach other subjects. Last year beginners’ sessions were offered in Russian, Afrikaans, Portuguese, Spanish or Greek. In the summer, we have an entire day dedicated to French. Learners visit a recreation of a French café (complete with French food, drink and music), complete quizzes, make posters of Francophone countries and prepare for an afternoon performance of “Les Trois Mousquetaires”.

5. Make life-long memories abroad

All our learners who study German have the opportunity to participate in an exchange to Schopfheim in southwest Germany, and to host their German partner on the return visit. Towards the end of the summer term Years 7 and 10 go on a cultural and study trip to France. The Italian students are offered study trips in the summer and autumn terms to Urbania, where they stay with local families, attend language lessons and do cultural activities.

Alison Pateman is a member of the MFL department at The Broxbourne School, a NACE member and Challenge Award-accredited secondary school and sixth form in Hertfordshire. She has been an MFL teacher for 25 years. She teaches French and German and has a particular interest in teacher and pupil creativity in language learning.

Tags:

creativity

enrichment

KS3

KS4

languages

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Chloe Maddocks,

29 January 2018

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

London’s renowned Saatchi Gallery is known for championing the work of previously unheard-of artists, offering a springboard to fame. Living up to this reputation, in March this year the gallery will feature work by some of the UK’s youngest and least-publicised artists – displaying creations from a cross-disciplinary project completed by Year 4 learners at NACE member and Challenge Award-accredited Pencoed Primary School.

Titled “Creating our Welsh identity”, the project started with a focus on learners identified as at risk of underachieving, including the more able – but its success led to elements being rolled out across the entire year group, and the school.

Class teacher Chloe Maddocks, who coordinated the project, explains more…

The context:

Promoting creativity and creative thinking is part of our school vision, and we recognise these as key life skills. However, this was an area we felt we could develop further.

We developed the “Creating our Welsh identity” project with the aim of raising academic attainment, improving learners’ self-esteem and confidence, and developing their creative skills – combined with a focus on numeracy and links to the year group topic. We also wanted to explore learner and staff perceptions of what it means to be creative, and to develop this thinking and awareness of broader creativity.

Having scoped out the project, we successfully applied through the Arts Council of Wales for a grant of £10,000, to be split between Year 1 (2016-17) and Year 2 (2017-18).

The project:

Running for the duration of the spring term, the project was linked to the Year 4 theme, The Stuarts. Initially, we selected 18 learners, targeting those at risk of underachieving. Due to the project’s success, we subsequently adopted some of the broader approaches across the rest of the year group and throughout the school.

At the start, learners did some research around the history of the Union Jack. Exploring symmetry, measuring and shapes, they then created their own version of the flag using fabric and donated materials, incorporating aspects of their own identity. Members of the community volunteered to teach learners to use a sewing machine, so they could stitch on their initials. The group also created personal identity drawings, based on research into the history of their family, incorporating words and symbols that represented them inside an outline of their body.

Numeracy was embedded from the start, right through to the end. We incorporated this in planning so all 60 learners within the year group were also taking part in the numeracy tasks. We looked at which National Literacy and Numeracy Framework (LNF) strands we could include, as well as planning our maths, language and topic lessons around the project. Focusing on real-life problems and tasks that reinforced specific numeracy strands – pricing activities, comparing costs from different supermarkets, profits and budgeting – allowed learners to relate to the importance of numeracy in everyday life.

More able and talented (MAT) learners were selected to act as leaders of certain parts of the project and were given the task of planning and coordinating the celebration event. All activities were differentiated to provide appropriate levels of challenge, and weekly evaluations allowed staff to tailor sessions to meet learners’ needs.

Learner engagement:

During the project we worked alongside Haf Weighton, a textile artist from Penarth. Haf brought some lovely ideas and had a wonderful working relationship with both the adults and children involved. She was selected by the learners themselves through an interview process, inspiring them with her style of art and her passion and love for her work.

Throughout, the learners were a key influence in determining the project’s direction, and were particularly active in devising the final outcome – the afternoon tea party. I had weekly conversations with them, in which they were able to evaluate their own work and the work of Haf, as well as discussing ways for the project to develop.

Celebration and exhibition:

To celebrate their work, learners hosted an afternoon tea party for parents and carers, sharing the project outcomes and showing off what they had learned throughout the topic. Around this event, learners had the opportunity to:

- Work alongside a candle maker

- Work alongside members of the community to create cushions and print

- Research what types of foods would have been served at a Stuart tea party

- Research the history of afternoon tea

- Take a trip into Pencoed village to purchase food

- Work out pricing, budget and profit

- Be filmed and interviewed by Heno, S4C

On the day of the party, parents and carers had the opportunity to sit in on either a literacy or numeracy lesson, tailored to the theme of the Stuarts.

Through Haf’s connections, we’ve also been able to reach a much wider audience. The artwork created was displayed in our very own exhibition in the HeARTh Gallery at the Llandough Hospital. Haf also shared details of the project at the Knit and Stitch Show in London, and – after the success of the project was shared online through our school website and Twitter – the prestigious Saatchi Gallery was very interested to work alongside Haf and to share the learners’ work.

Impact:

The impact for learners was far greater than we initially anticipated. All made progress with their weekly Big Maths scores and overall numeracy skills. They were also able to see the benefits of numeracy in everyday tasks, benefitting from the cross-curricular approach.

As well as developing a multitude of literacy, numeracy and creative skills, there was also an improvement in learners’ general confidence, wellbeing and self-esteem. For MAT learners, independent thinking and problem solving improved, and all learners felt a strong sense of pride and achievement in their work. Opportunities to see their work displayed, and to share their learning with parents and carers, provided inspiration to broaden their horizons and aspirations for the future.

There’s also been a wider impact, as we’ve shared the excellent practice across the school. In addition, the project has raised awareness about the importance of creativity among learners, staff and parents, showcasing how much can be achieved.

Next steps:

We are now in our second year of this project, and intend to continue running projects in this way. We’ve also been involved in school-to-school collaboration and shared our experiences in networking events across the Central South Consortium to promote this project to other schools. And of course we’re also planning to take the learners to the Saatchi Gallery in March, so they can experience the exhibition first-hand!

Chloe Maddocks has been a full-time teacher at Pencoed Primary School for four years, teaching Years 3 and 4. As coordinator of the “Creating our Welsh identity” project, she’s enjoyed opportunities to develop her leadership and project management skills, learner engagement, and share expertise with peers at other schools. She’s passionate about showing how creative skills can be incorporated into cross-curricular learning.

Pencoed Primary School has been a NACE member since 2014 and achieved the NACE Challenge Award in July 2015. With approximately 600 learners enrolled, the school is dedicated to developing networks of good practice and continually reviewing and improving its provision for all learners within an ethos of challenge for all.

Do you have an inspiring project to share with the NACE community? Contact us to share a case study.

Tags:

arts

creativity

enrichment

KS2

Wales

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Christine Chen and Lindsay Pickton ,

18 January 2018

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

NACE associates Christine Chen and Lindsay Pickton are experienced primary English advisors, with a specialisation in supporting more able learners. In this blog post, they explain how grammar games can help to foster creativity, engagement with the composition process, and a lasting love of language.

If you’re not already using grammar games in your classroom, here are five reasons to start now…

1. They set a high bar for all learners

The great thing about grammar games is that they enable a “low threshold, high ceiling” approach to learning, enabling all learners to experience the possibilities of language manipulation. While some games offer potential forms of differentiation, the key – as with any learning – is having high expectations of all.

2. They’re fun!

There’s a common misconception that grammar is intrinsically boring and dry. Grammar games help to break this down, providing opportunities for teachers and learners alike to have fun with grammar, through activities including dice games, physical manipulation of sentence structures and simple drama strategies.

3. They put grammar in context

Grammar teaching and learning is commonly approached through isolated exercises, which may help some children with test preparation, but do little to support composition. Grammar games can be used to explore grammar in the wider context of language usage, making it more likely that learners will apply new learning and continue to experiment.

4. They encourage risk-taking

Collaborative grammar play transforms what could be a purely internal process into an enjoyable shared learning experience. When children experiment with application in writing following these collaborative games, they are more likely to take risks and to feel in control, in a joyful way.

5. They nurture a love of language

Playing with language fosters a love of it. This is important for all learners, including more able writers and communicators. Even if they don’t know the terminology, these learners are able to adapt sentence structures and vocabulary choices to achieve a desired impact on their readership. Grammar games further encourage them to take pleasure in exploring and developing their skills as young writers.

One to try: “Every word counts”

This is a dice game for manipulating meaning and exploring nuance through vocabulary choices. It’s one of the most popular and adaptable games we’ve invented; as children play, they experience tangibly the descriptive power of every word in a sentence.

Create a six-word sentence, in which no word class is repeated, and list the word classes in order.

e.g. They played in their tiny garden.

- Pronoun

- Verb

- Preposition

- Determiner

- Adjective

- Noun

Throw a dice. With each throw, children must change the corresponding word in the sentence, and discuss (as a group or whole class) what has changed about the scene or story.

e.g. Throw a 4 – change the determiner:

- They played in their tiny garden.

- They played in her tiny garden.

- They played in the tiny garden.

- They played in this tiny garden.

Learners discuss how changes made affect the meaning. With each change, how does the word choice affect the story?

Tags:

creativity

English

language

oracy

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Sarah Carpenter,

16 January 2018

Updated: 03 November 2020

|

Getting to grips with mastery doesn’t have to be hard work – far from it. In this blog post (originally published on schoolsimprovement.net), NACE associate Sarah Carpenter outlines a simple but effective use of mastery to improve primary English provision for all learners, including the more able…

While teachers and schools are at different points in the maths mastery journey, it’s now fairly clear what that looks like and what’s expected. When it comes to English, however, there’s relatively little guidance on how to use mastery effectively.

Inspired by Michael Tidd’s advocacy of longer literacy units, covering fewer texts and focusing on writing for a social purpose, over the past three years I’ve worked with schools to develop a mastery approach for primary English. This is certainly not the only approach to mastery in English, but it is an approach that I and the schools involved have found effective.

The concept is simple: each half term the teacher selects a central “driver text”. This is paired with a range of supplementary texts, including fiction, poetry, non-fiction, multimodal texts, and cross-curricular links. The unit is planned around the driver text, building in curriculum requirements and a broad range of writing opportunities.

This approach gives all learners the opportunity to develop a secure understanding of the driver text, subject matter and key skills – as well as the scope to work in greater depth and to explore and showcase their creativity and writing abilities.

Here are six reasons to try this mastery approach in your primary English provision:

1. It works for learners of all abilities

First and foremost, mastery is about providing support and opportunities for learners of all abilities to develop at their own pace. This approach allows time for all learners to become familiar with the central text and subject matter, and to practise specific skills such as predicting, comparing, making connections and synthesising.

For learners working below age-related expectations, you’re not moving on too quickly, and there are opportunities to consolidate skills through repetition. At the other end of the spectrum, more able learners have opportunities to broaden their knowledge and understanding of the writing purpose, bring together multiple texts, and deepen their subject knowledge.

The inclusion of poetry in each unit helps to expand learners’ vocabulary and get them thinking creatively about the choices they’re making. The use of non-fiction and cross-curricular texts provides opportunities for the more able to make clever use of sources, and to play with their writing styles, taking the audience and purpose into account. They have a bigger toolbox to draw on, allowing them to really show off their finesse as writers.

2. It engages even reluctant writers

When choosing a driver text, I try to choose one that will capture the interest of everyone in the class, particularly keeping boys in mind. Then I plan the unit to incorporate a wide variety of writing opportunities – short, medium and long – so even reluctant writers face something manageable and interesting, that breaks the mould in terms of what they’re usually asked to write.

3. It develops deep subject knowledge

Bringing in supporting texts with a shared theme allows learners to develop a deep sense of subject knowledge, so they can write as experts in the field. Just as a published author wouldn’t start writing without doing their background research first, we’re setting the same expectation for our pupils. This approach resonates very much with highly able learners in English.

4. It makes more effective use of time

This approach takes up no more or less time than would already be used for literacy sessions, but makes more effective use of that time. Covering fewer texts in a more focused way means more time to get deeply into the full range of curriculum requirements – in terms of reading, writing, drama and spoken language. You can even use the driver text or an accompanying text for guided reading sessions, so everything is working together.

In terms of planning, you do need to allocate more time at the beginning, because you’re essentially planning out the full half term in skeletal form. You can adapt as you go along, but you need to plan ahead to ensure you extract everything you can from the driver text and stop at the right points, building up that sense of mystery and anticipation, and allowing for reading and writing opportunities along the way.

Once you’ve chosen the driver text, you’re looking for those opportunities to bring in non-fiction, and searching for appropriate poetry connections. Once you’ve done this groundwork, you should find you spend less time on weekly planning, because you’ve got the framework in place.

5. It works for all types of text…

…even (or especially) picture books! I often choose picture-based story books or graphic novels, such as David Wiesner’s Flotsam or Shaun Tan’s The Arrival – which can be interesting when you tell people the unit is going to improve children’s vocabulary and grammar! Other driver texts I’ve used include Robert Swindells’ The Ice Palace, Rob Biddulph’s Blown Away, Helen Cooper’s Pumpkin Soup and Alexis Deacon’s I am Henry Finch.

Essentially, you’re looking for a text where you see lots of potential to go off at all sorts of different angles, and bring in cross-curricular links. For example, with I am Henry Finch, there are lots of links to be made with PSHE.

6. It’s fun!

Last but certainly not least, this mastery approach is fun. I’ve developed units for KS1, lower KS2 and upper KS2, with positive feedback from all. Not only have schools got some fantastic writing and reading responses from learners, but the children have really enjoyed it. They appreciate the opportunity to get deeply into one particular text – but not to the extent where they get bored, because they’ve got the addition of other texts of different types, and the scope to show off just what they can do.

Tags:

creativity

English

KS1

KS2

literacy

mastery

reading

writing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Lesley Hill,

06 November 2017

Updated: 22 December 2020

|

Lesley Hill, headteacher of NACE member Lavender Primary School in North London, shares her school’s approach to ensuring the curriculum remains broad, engaging and meaningful – alongside a successful focus on good outcomes for all learners.

“Lavender” School conjures images of a delightful school in a leafy suburb. It is a delightful school, but we have our challenges. The number of children with English as an additional language, and of those eligible for FSM, are both above national averages. We also have a high number of children with need. However, challenges are not just about closing gaps, and when it comes to curriculum one particular challenge is to hold on to what is important.

In the late 80s, I was an advocate of themes, of helping children see links in learning and maximising creativity. Although I understood the need for a national curriculum (to avoid children potentially repeating the same topic year after year!), I had serious concerns about a rigid, dictated and narrow curriculum that would merely feed standardised tests.

A few decades (and curriculum reviews) on, and I don’t believe that prescription has to stifle creativity, or that children have to learn within a narrow framework to get results.

Empowering learners to make choices… and mistakes

For some years, most of our subject teaching has been done through cross-curricular topics and we insist on at least one pupil choice topic per year. Classes or year groups vote on different themes and teachers ensure that the statutory knowledge and skills are covered within the topic. In KS2, we aim to include children in the planning process by asking them to consider how the required topic content could be taught.

Our use of pupil voice helps to engage and motivate our learners, but we also want them to have ownership over their learning. The introduction of growth mindset five years ago made a marked difference in terms of attitude, and was particularly empowering for those higher-achieving learners who find it so hard to “get something wrong”.

Developing skills for self-evaluation and reflection

Learning to learn strategies were also embedded and this culture enabled us to introduce fast, effective feedback a year ago. Teachers do not write in any books, but mark verbally during lessons, through 1:1 or group conferencing. Children peer- and self-assess and write reflections on their learning against success criteria. The self-evaluative process needs higher-order thinking, and allows learners at all levels to develop those skills.

Meta-cognition is promoted through peer work and is particularly successful for higher achievers when working with lower achieving or younger children (such as through our Reading Buddy scheme). Talk partners are therefore picked randomly to allow a range of peer-work experience. Group and paired feedback has been successful across the curriculum. I opened a sketch book recently and read, “I spoke with my partner and we thought that I should put more shading and detail on the petals.” Our “drafting and crafting” approach is used across the curriculum, enabling children to reflect on all learning, not just the core subjects.

Encouraging creativity at home

The fact that we value all subjects is visible in our homework policy. Learners have the usual spellings and number facts to learn, but also work on given topic themes. Because the titles are quite open (such as “Enfield Town”), children can access them and deepen their learning according to their own starting points. On home-learning day, you might see children carefully manoeuvring a model volcano, clutching a home-made booklet about local history or a USB stick with a slideshow about chocolate. They might just have a sheet of notes that have been prepared for a “lecture”. They share these projects at school, paying special attention to their presentation skills, which are then peer- and self-evaluated.

Extracurricular experiences and engagement

Visits and outings are built into our curriculum. We develop enterprise and aspiration through trips to businesses and institutions, such as Cambridge University, and by inviting in key people. We value working with others, getting involved with school cluster creative projects wherever possible. Last year, we were able to buy in a British Sign Language (BSL) teacher from a partner school to teach sign language to every class from nursery to Y6. We also encourage entries to events such as the annual Chess Tournament and Mayor’s Award for Writing, and are in the process of organising a spelling bee across our partner schools.

Home-school partnerships are important to us. Family days, where parents come in and work alongside their children, as well as exhibitions and information fairs, help us to share our wider curriculum. One event saw parents being led on a tour through the WWI trenches and, last year, families came in to learn the school song (written by the children themselves). We also work to build wider community links through events such as bulb planting with the local park group, or charity choir performances. Our School Council representatives are confident and vocal when considering local and wider issues and how we can support others.

What does it all mean?

Lavender's results are very pleasing across all key stages. Our GLD, phonics, KS1 and KS2 combined outcomes remain above national figures, with progress data of our higher-achieving children being better than national in all subjects.

OK, so Year 6 do have to do practice tests and more homework than most, but you'll still catch them sneaking into my office during a unit on mystery texts, going through my bin, and desperately trying to work out if I'm actually a spy. Despite budget pressures, I will continue to find the money for Herbie's insurance (our school dog's work with the most vulnerable children is priceless) and I’ll always value our subject leaders for the passion and drive they bring to our curriculum.

Data will always be top of my agenda, but it's there alongside breadth, depth and enrichment. A broad and balanced curriculum doesn't have to be at the expense of good outcomes for our children.

Lesley Hill is headteacher of Lavender Primary School, a popular two-form entry school in North London, part of the Ivy Learning Trust and a member of NACE. She has taught across the primary age range and has also worked in adult basic education and on teacher training programmes. Her current role includes the design and delivery of leadership training at middle and senior leader level, and she also provides workshops on a range of subjects, such as growth mindset and marking. Her book, Once Upon a Green Pen, which explores creating the right school culture, is due to be released early next year.

Tags:

creativity

curriculum

enrichment

metacognition

mindset

parents and carers

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|