Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

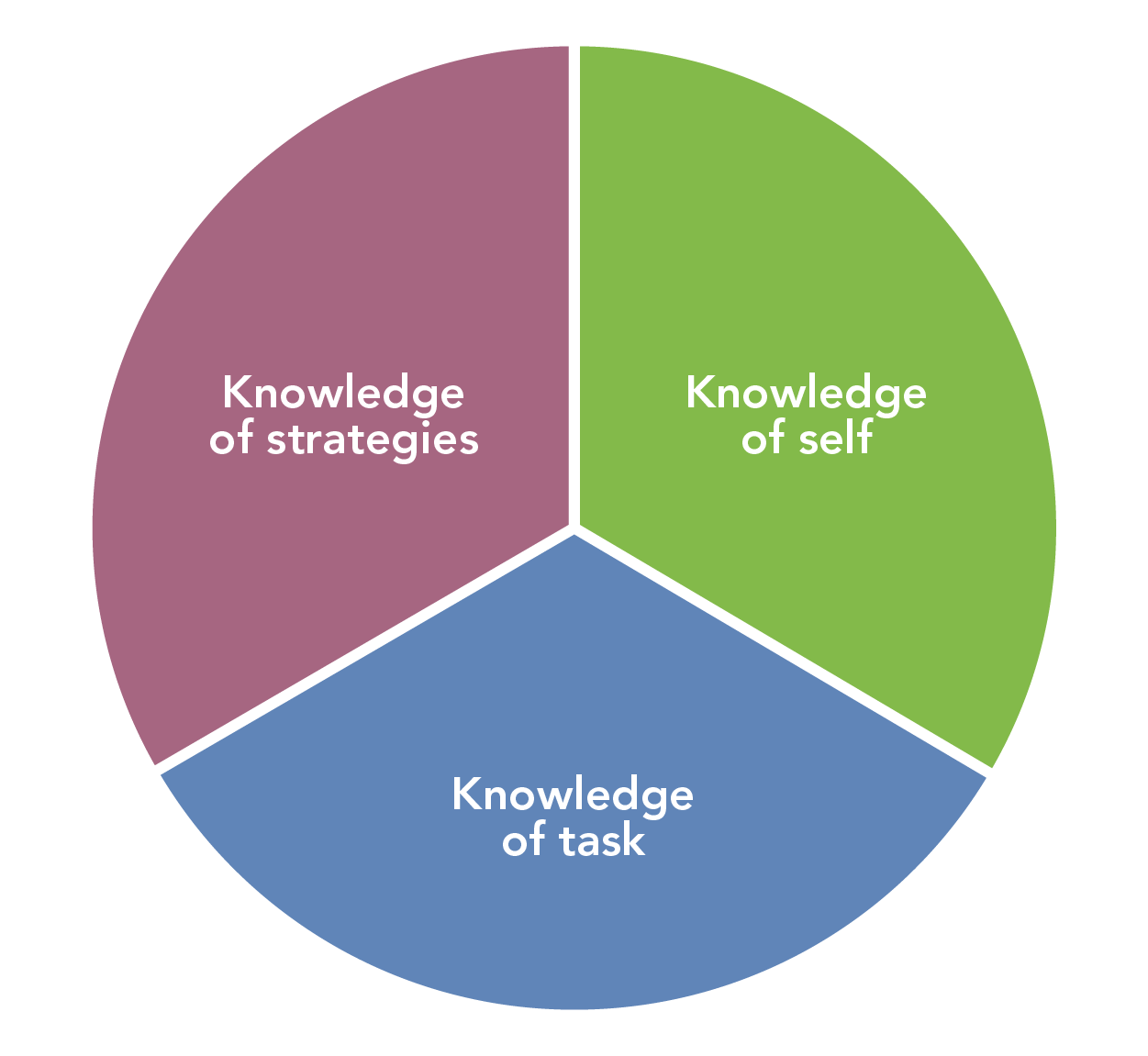

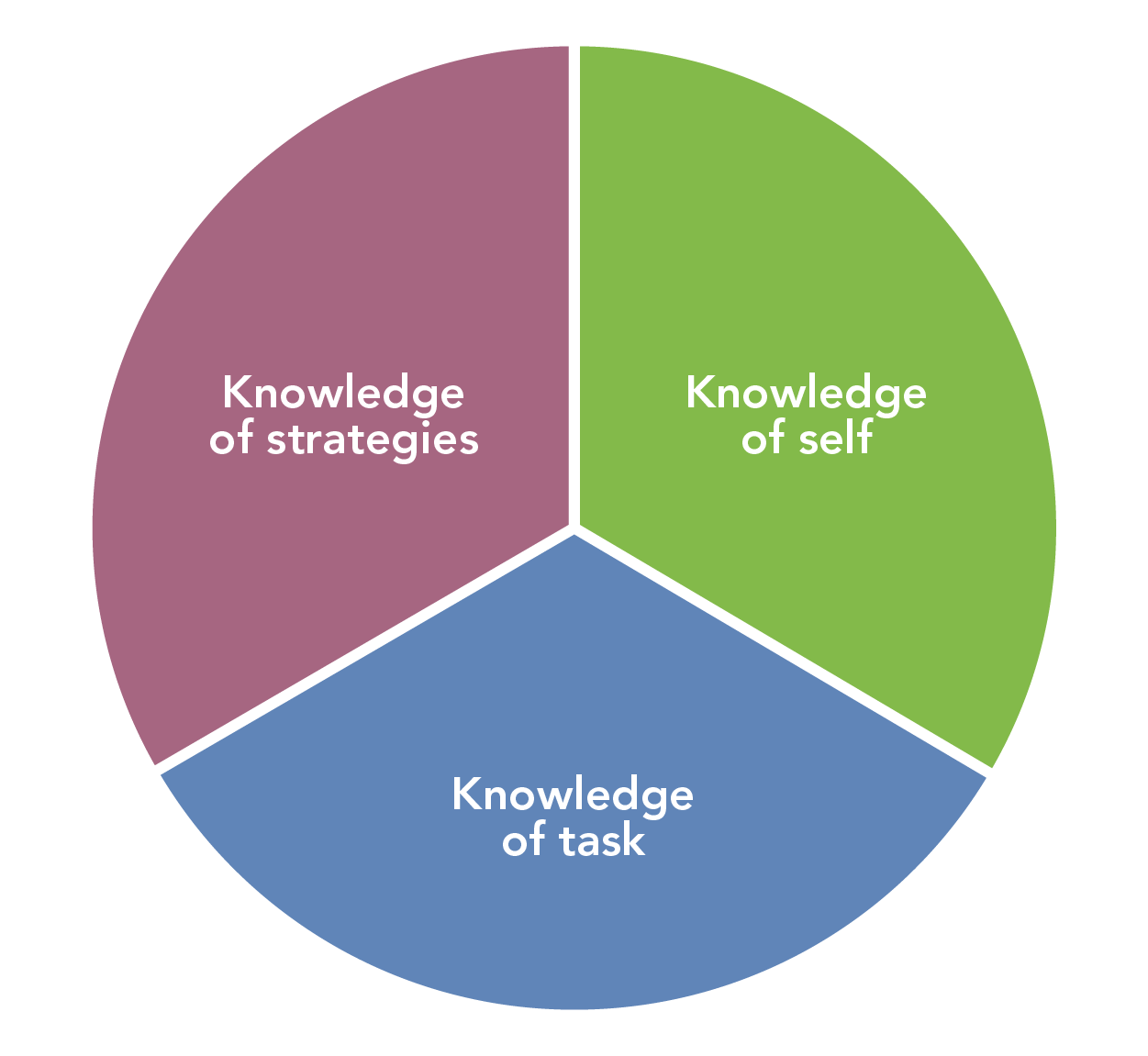

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

22 March 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Curriculum Development Director

What I Talk About When I Talk About Running by Haruki Murakami is one of my favourite books… even if reading it did not make me run faster. The title did, however, lead me to ask students: “What do you think about when you think about learning?” This is not an easy question to answer. We increasingly recognise the importance of developing metacognition in learning and the need to challenge pupils cognitively, but this is not always easy in the mixed ability classroom.

In the NACE report Making space for able learners – Cognitive challenge: principles into practice (2020), cognitive challenge is defined as “ how learners become able to understand and form complex and abstract ideas and solve problems”. We want students to achieve these high ambitions in their learning, but how is this achieved in a mixed ability class with increasing demands on the teacher, including higher academic expectations? The NACE report provides case studies showing where this has been achieved and highlights the common features across schools that are achieving this – and these key themes are worth reflecting upon. What do we mean by “challenge for all”?

“Challenge for all” is the mantra often recited, but is it a reality? At times it can appear that “challenge” is just another word for the next task. Or, perhaps, just a name for the last task. Working with teachers recently I asked: why do the more able learners need to work through all the preceding the tasks to get to the “challenge”? Are you asking them to do other work that is not challenging? Or coast until it gets harder? A month later the same teachers talked about how they now move those learners swiftly on to the more challenging tasks, noting that their work had improved significantly, they were more motivated and the learning was deeper. This approach also led to learners being fully engaged, meaning the teacher could vary the support needed across the class to ensure all pupils were challenged at the appropriate level.

“Teaching to the top” is another phrase widely used now and it is a good aspiration, although at times it is unclear what the “top” is. Is it grade 7 at GCSE or perhaps greater depth in Year 6? It is important to have these high expectations and to expose all learners to higher learning, but we need to remember that some of our learners can go even higher but also be challenged in ways that do not relate to exams. For instance, at Copthorne Primary School, the NACE report notes that “pupils are regularly set complex, demanding tasks with high-level discourse. Teachers pitch lessons at a high standard”. Note the reference to discourse – a key feature of challenge is the language heard in the classroom, whether from adults or learners. The “top” is not merely a grade; it is where language is rich and learning is meaningful, including in early years, where we often see the best examples.

Are your questions big enough?

The use of “low threshold, high ceiling” tasks are helpful in a mixed ability class, with all pupils able to access the learning and some able to take it further. In maths, a question as simple as “How many legs in the school?” can lead to good outcomes for all (including those who realise the question doesn’t specify human legs). But there is often a danger that task design can be quite narrow. The minutiae of the curriculum can push teachers to bitesize learning, which can be limiting – especially when a key aim has to be linking the learning through building schema. Asking “Big Questions” can extend learning and challenge all learners. The University of Oxford’s Oxplore initiative offers a selection of Big Questions and associated resources for learners to explore, such as “Should footballers earn more than nurses?” and “Can money buy happiness?”. There is a link to philosophy for children here, and in cognitively challenging classrooms we see deep thinking for all pupils. Can your learners build more complex schema?

All pupils need to build links in their learning to develop understanding, and more able learners can often build more detailed schema. To give a history example, understanding the break from Rome at the time of Henry VIII could be learned as a series of separate pieces of knowledge: marriage to Catherine of Aragon, the need for a male heir, wanting a divorce in order to marry Anne Boleyn, the religious backdrop, etc. Knowing these items is one thing, but learners need to make links between them and create a schema of understanding. The more able the pupil, the more links can be made, again deepening understanding. That is why in cognitively challenging classrooms skilled teachers ask questions such as:

- What does that link to?

- What does that remind you of?

- When have you seen this before?

- What is this similar to? Why?

These questions are especially useful in a busy mixed ability classroom. Prompt questions like these can be used in a range of situations, rather than always requiring another task for the more able pupil who has “finished”. (As if we have ever really finished)

Are you allowing time for “chunky” problems?

So, what else provides challenge? The NACE report notes: “At Portswood Primary School pupils are given ill-structured problems, chunky problems, and compelling contexts for learning”. Reflecting upon the old literacy hour, I used to joke: “Right Year 5, you have 20 minutes to write like Charles Dickens. Go!” How could there be depth of response and high-level work in such short time scales? What was needed were extended tasks that took time, effort, mistakes, re-writes and finally resolution. The task often needed to be chunky. Some in the class will need smaller steps and perhaps more modelling from the teacher, but for the more able learners their greater independence allows them to tackle problems over time.

This all needs organising with thought. It does not happen by accident. With this comes a sense of achievement and a resolution. Pupils are challenged cognitively but need time for this because they become absorbed in solving problems. This also works well when there are multiple solution paths. In a mixed ability class asking the more able to find two ways to solve a problem and then decide which was the most efficient or most effective can extend thinking. It also calls upon higher-order thinking because they are forced to evaluate. Which method would be worth using next time? Why? Justify. This also emphasises the need to place responsibility with the learner. “At Southend High School for Boys, teachers are pushed to become more sophisticated with their pedagogy and boost pupils’ cognitive contribution to lessons rather that the teacher doing all the work”. In a mixed ability class this is vital. How hard are your pupils working and, more importantly, thinking?

I wrote in a previous blog post about how essential the use of cutaway is in mixed ability classes. Retrieval practice, modelling and explanation are vital parts of a lesson, but the question is: do all of the students in your class always need to be part of that? A similar argument is made here. More able learners are sometimes not cognitively challenged as much in whole-class teaching and therefore, on occasion, it is preferable for these pupils to begin tasks independently or from a different starting point.

As well as being nurturing, safe and joyful, we all want our classrooms to be cognitively challenging. This is a certainly not easy in a mixed ability class but it can be achieved. High expectations, careful task design and an eye on big questions all play a part, alongside the organisation of the learning. In this way our teaching can be improved significantly – far more than my running ever will be…

Related blog posts

Additional reading and support

Tags:

cognitive challenge

grouping

metacognition

problem-solving

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Robin Bevan,

08 March 2021

|

Dr Robin Bevan, Headteacher, Southend High School for Boys (SHSB)

One of the underlying tests of whether a student has fully mastered a new area of learning is whether they have the capacity to “self-regulate the production of quality responses” in that domain. At its simplest level, this would be knowing whether an answer is right or not, without reference to any third party or expert source. This develops and extends into whether the student can readily assess the validity of the reasoning deployed in replying to a more complex question. And, at its highest level, the student would be able to articulate why one response to a higher-order question is of superior quality than another.

Framed in another way, we teach to ensure that our pupils know how to answer questions correctly, know what makes their responses sound and, ultimately, understand the distinguishing features of the best quality thinking relevant to the context (and, by this I mean far more than just the components of a GCSE mark scheme).

This hierarchy of desired learning outcomes not only provides an implicit structure for differentiating task outcomes, but also gives a strong steer regarding our approaches to feedback for the most able learners. Our intention for our most able learners is that they can reach the highest level of critical understanding with each topic. This is so much more than just getting the answers right and hints at why traditional tick/cross approaches to marking have often proved so ineffective (Ronayne: 1999).

These comments may be couched in different language, but there is a deep resonance between my observations and the clarion call – over two decades ago – for increased formative assessment that was published as Inside the Black Box (Black and Wiliam, 1998):

Many of the successful innovations have developed self- and peer-assessment by pupils as a way of enhancing formative assessment, and such work has achieved some success with pupils from age five upwards. This link of formative assessment to self-assessment is not an accident – it is indeed inevitable.

To explain this, it should first be noted that the main problem that those developing self-assessment encounter is not the problem of reliability and trustworthiness: it is found that pupils are generally honest and reliable in assessing both themselves and one another, and can be too hard on themselves as often as they are too kind. The main problem is different – it is that pupils can only assess themselves when they have a sufficiently clear picture of the targets that their learning is meant to attain. Surprisingly, and sadly, many pupils do not have such a picture, and appear to have become accustomed to receiving classroom teaching as an arbitrary sequence of exercises with no overarching rationale. It requires hard and sustained work to overcome this pattern of passive reception. When pupils do acquire such an overview, they then become more committed and more effective as learners: their own assessments become an object for discussion with their teachers and with one another, and this promotes even further that reflection on one's own ideas that is essential to good learning.

What this amounts to is that self-assessment by pupils, far from being a luxury, is in fact an essential component of formative assessment. Where anyone is trying to learn, feedback about their efforts has three elements – the desired goal, the evidence about their present position, and some understanding of a way to close the gap between the two (Sadler: 1989). All three must to a degree be understood before they can take action to improve their learning. (Black & Wiliam, 1998)

Understanding the needs of the more able: a tragic parody

Sometimes an idea can become clearer when we examine its opposite: when, that is, we illuminate how the more able learner can be starved of effective feedback. To illustrate this as powerfully as possible, I am going to employ a parody. It is a tragic parody, in that the disheartening description of teaching and learning that it includes is both frustratingly common and yet so easily amenable to fixing. Imagine the following cycle of teacher and pupil activity.

- The teacher identifies an appropriate new topic from the scheme of work. She delivers an authoritative explanation of the key ideas and new understanding. It is an accomplished exposition and the class is attentive.

- A set of response tasks are set for the class. These are graduated in difficulty. Every pupil is required to work in silence, unaided – after all, it has just been explained to them all! Each pupil starts with the first question and continues through the exercise. The work is completed for homework.

- The teacher collects in the homework, marks the work for accuracy of answers with a score out of 10.

- In the next lesson, the class is given oral feedback by the teacher on the most common errors. The class proceeds to the next topic. The cycle then repeats.

This is probably not far removed from the way in which many of us were taught, when we were at school. Let us examine this parody from the perspective of the more able.

- It is highly likely that the more able pupil already knows something, or a great deal, about this topic. Nonetheless, complicit in this well-rehearsed didactic model, the most able pupil sits through the teacher’s presentation, patiently. A good proportion of this time is essentially wasted.

- Silent working prohibits the development of understanding that comes through vocal articulation and discussion. The initially easy exercise prevents, by its very design, the most able from exploring the implications and higher consequences of the topic. The requirement to complete all the questions, even the most simple, fills the time – unproductively. Then, the whole class faces the challenge of completing the harder questions, unsupported, away from the teacher’s expert assistance. For the most able, these harder questions are probably the richest source of potential new learning. But it is no surprise that for the class as a whole the success rate on the harder questions is limited.

- The most able pupil gains 8 or 9 out of 10; possibly even an ego-boosting 10. The pupil feels good and is inclined to see the task as a success. Meanwhile, all the items that are discussed by the teacher were questions that everyone else got wrong, not the learning that is needed to extend or develop the more able pupil.

- A new topic is started. The teacher has worked hard. The class has been well-behaved. The able pupil has filled their time with active work. And yet, so little has been learned.

Unravelling the parody

This article is intended to focus on the most effective forms of feedback for the more able learner; but it is clear from the parody that we are unlikely to create the circumstances for such high-quality feedback without considering, alongside this, elements such as: the diagnostic assessment of prior learning, structured lesson design, optimal task selection, and effective homework strategies. Each of these, of course, warrants an article of its own.

However, we cannot escape the role of task design altogether in effective feedback. A variety of routine approaches, often suited for homework, allow students to become accustomed to the process of determining the quality of what might be expected of their assignments. For example:

a. Rather than providing marked exemplars, pupils are required to apply the mark scheme to sample finished work. Their marking is then compared (moderated), before the actual standards are established. This ideally suits extended written accounts and practical projects.

b. Instead of following a standard task, pupils are instructed to produce a mark scheme for that task. Contrasting views and key features of the responses are developed; leading to a definitive mark scheme. (It may then be appropriate to attempt the task, or the desired learning may well have already been secured.) This ideally suits essays and fieldwork.

c. These approaches may be adapted by supplying student work to be examined by their peers: “What advice would you give to the student who produced this?” “What misunderstanding is present?” “How would you explain to the author the reasons for their grade?” This ideally suits more complex conceptual work, and lines of reasoning.

d. As a group activity, parallel assignments may be issued: each group being required to prepare a mark scheme for just one allocated task, and to complete the others. Ensuring that the mark schemes have been scrutinised first, the completed tasks are submitted for assessment to the relevant group. This ideally suits examination preparation.

Although these are whole-class activities, they are particularly suited to the more able learner as they give access to higher-order reflective thinking and the tasks are oriented around the issue of “what quality looks like”.

Marking work or just marking time?

Teachers spend extended hours marking pupils’ work. It is a common frustration amongst colleagues that these protracted endeavours do not always seem to bear fruit. There are lots of reasons why we mark, including: to ensure that work has been completed; to determine the quality of what has been done; and to identify individual and common errors for immediate redress.

The list could be extended, but should be reviewed in the light of one pre-eminent question: to what extent does this marking enhance pupils’ learning? The honest answer is that there are probably a fair number of occasions when greater benefit could be extracted from this assessment process.

The observations of Ronayne (1999) illustrate this concern and have clear implications for our professional practice with all learners, but perhaps the most able in particular. In his study, Ronayne found that when teachers marked pupils’ work in the conventional way in exercise books, an hour later, pupils recalled only about one third of the written comments accurately – although they recalled proportionately more of the “constructive” feedback and more of the feedback related to the learning objectives.

Ronayne also observed that a large proportion of written comments related to aspects other than the stated learning objectives of the task. Moreover, the proportion of feedback that was constructive and related to the objectives was greater in oral feedback than written; but as more lengthy oral feedback was given, fewer of the earlier comments were retained by the class. In contrast, individual verbal feedback, as opposed to whole-class feedback, improved the recollection of advice given.

So what then should we do?

It is usually assumed that assessment tasks will be designed and set by the teacher. However, if students understand the criteria for assessment in a particular area, they are likely to benefit from the opportunity to design their own tasks. Thinking through what kinds of activity meet the criteria does, itself, contribute to learning.

Examples can be found in most disciplines: pupils designing and answering questions in mathematics is easily incorporated into a sequence of lessons; so is the process of identifying a natural phenomenon that demands a scientific explanation; or selecting a portion of foreign language text and drafting possible comprehension questions.

For multiple reasons the development of these approaches remains restricted. There is no doubt that teachers would benefit from practical training in this area, and a lack of confidence can impede. However, it is often the case that teachers are simply not convinced of the potency of promoting self-regulated quality expertise.

A study in Portugal, reported by Fontana and Fernandes in 1994, involved 25 mathematics teachers taking an INSET course to study methods for teaching their pupils to assess themselves. During the 20-week part-time course, the teachers put the ideas into practice with a total of 354 students aged 8-14. These students were given mathematics tests at the beginning and end of the course so that their gains could be measured. The same tests were taken by a control group of students whose mathematics teachers were also taking a 20-week part-time INSET course but this course was not focused on self-assessment methods. Both groups spent the same time in class on mathematics and covered similar topics. Both groups showed significant gains over the period, but the self-assessment group's average gain was about twice that of the control group. In the self-assessment group, the focus was on regular self-assessment, often on a daily basis. This involved teaching students to understand both the learning objectives and the assessment criteria, giving them an opportunity to choose learning tasks, and using tasks that gave scope for students to assess their own learning outcomes.

Other studies (James: 1998) report similar achievement gains for students who have an understanding of, and involvement in, the assessment process.

One of the distinctive features of these approaches is that the feedback to the student (whether from their own review, from a peer or from the teacher) focuses on the next steps in seeking to improve the work. It may be that a skill requires practice, it may be that a concept has been misunderstood, that explanations lack depth, or that there is a limitation in the student's prior knowledge.

Whatever form the feedback takes, it loses value (and renders the assessment process null) unless the student is provided with the opportunity to act on the advice. The feedback and the action are individual and set at the level of the learner, not the class.

In a similar vein, approaches to “going through” mock examinations and other tests require careful preparation. Teacher commentary alone, whilst resolving short-term confusion, is unlikely to lead to long-term gains in achievement. Alternatives are available:

i. Pupils can be asked to design and solve equivalent questions to those that caused difficulty;

ii. Pupils can, for homework, construct mark schemes for questions requiring a prose response, especially those which the teacher has identified as having been badly answered;

iii. Groups of pupils (or individuals) can declare themselves “experts” for particular questions, to whom others report for help and to have their exam answers scrutinised.

Again, in each of these practical approaches the most able are positioned close to the optimal point of learning as they articulate and demonstrate their own understanding for themselves or for others. In doing so, they can confidently approach the self-regulated production of quality answers.

Further reading

- Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. School of Education, King’s College, London.

- Fontana, D. and Fernandes, M. (1994). ‘Improvements in mathematics performance as a consequence of self-assessment in Portuguese primary school children’. British Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol. 64 pp407-17.

- James, M. (1998) Using Assessment for School Improvement. Heinemann, Oxford.

- Ronayne, M. (1999). Marking and Feedback. Improving Schools. Vol. 2 No. 2 pp42–43.

- Sadler, R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science. Vol. 18 pp119-144.

From the NACE blog:

Additional support

NACE Curriculum Develop Director Dr Keith Watson is presenting a webinar on feedback on Friday 19 March 2021, as part of our Lunch & Learn series. Join the session live (with opportunity for Q&A) or purchase the recording to view in your own time and to support school/department CPD on feedback. Live and on-demand participants will also receive an accompanying information sheet, providing an overview of the research on effective feedback, frequently asked questions, and guidance on applications for more able learners. Find out more.

Tags:

assessment

feedback

independent learning

metacognition

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

08 March 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Curriculum Development Director and former CEO of Portswood Primary Academy Trust

“I once estimated that, if you price teachers’ time appropriately, in England we spend about two and a half billion pounds a year on feedback and it has almost no effect on student achievement.”

– Dylan Wiliam

So why do we do it? Primarily because the EEF toolkit identified feedback as one of the key elements of teaching that has the greatest impact. With this came the unintended consequence of an Ofsted handbook and inspection reports that criticised a lack of written feedback and response to pupils’ responses to marking which led to what became an unending dialogue with dangerous workload issues. At some point triple-marking seemed more about showing a senior leader or external inspector that the dialogue had happened. More recently, the 2016 report of the Independent Teacher Workload Review Group noted that written marking had become unnecessarily burdensome for teachers and recommended that all marking should be driven by professional judgement and be “meaningful, manageable and motivating”.

So what is “meaningful, manageable and motivating” in terms of marking and feedback for more able learners? Is it about techniques or perhaps more a question of style? At Portswood Primary Academy Trust our feedback has always been as close to the point of teaching as possible. It centres on real-time feedback for pupils to respond to within the lesson. Paul Black was kind enough to describe it as “marvellous” when he visited, so not surprisingly this is what we have stuck with. Teachers work hard in lessons to give this real-time feedback to shape learning in the lesson. The importance of this approach is that feedback is instant, feedback is relevant, and feedback allows pupils to make learning choices (EEF marking review 2016). But is there more to it for more able learners?

Getting the balance right

In giving feedback to more able learners the quality of questioning is crucial. This should aim to develop the higher-order skills of Bloom’s Taxonomy (analysing, evaluating and creating). A more facilitative approach should develop thinking. The questions should stimulate thought, be open, and may lead in unexpected directions.

A challenge for all teachers is how to balance feeding back to the range of attainment in a class. The recent Ofsted emphasis on pupils progressing through the programmes at the same rate is not always the reality for teachers. Curriculum demands are higher in core subjects, meaning teachers are under pressure to ensure most pupils achieve age-related expectations (ARE). The focus therefore tends to be more on pupils below ARE, with more time and effort focused there. The demands related to SEND pupils can also mean less teacher time devoted to more able pupils who have already met the standards.

Given that teachers may have less time for more able learners it is vital the time is used efficiently. For the more able it is less about the pupils getting the right answer, and more about getting them to ask the right questions. Detailed feedback in every lesson is unlikely so teachers should:

- Look at the week/unit as a whole to see when more detailed focus is timely;

- Use pre-teaching (such as in assembly times) to set up more extended tasks;

- Develop pupils’ independence and resilience to ensure there is not an over-reliance on the teacher;

- Identify times in lessons to provide constructive feedback to the more able group that would have the most impact.

Another tension for teachers is the relationship between assessment frameworks and creativity. For instance, at KS1 and KS2, the assessment criteria at greater depth in writing is often focused on technical aspects of writing. But is this stifling creativity? Is the reduction in students taking A-level English because of the greater emphasis on the technical at GCSE? As one able Year 10 writer commented, “Why do I have to focus on semicolons so much? Writing comes from the heart.” Of course the precise use of semicolons can aid writing effectively from the heart, but if the passion is dampened by narrow technical feedback will the more able child be inspired to write, paint or create? Teachers need to reflect on what they want to achieve with their most able learners.

Three guiding principles

So what should the guiding principles for feedback to more able learners be? Three guiding principles for teachers to think about are:

1. Ownership with responsibility

More able learners need to take more ownership of their work; with this comes responsibility for the quality of their work. Self-marking of procedural work and work that has a definitive answer (the self-secretary idea) allows for children to:

- Check – “Have I got it?”

- Error identify – “I haven’t got it; here's why”

- Self-select to extend – “What will I choose to do next?”

Only the last of these provides challenge. The first two require responsibility from learners for the fundamentals. The third leads to more ownership for pupils to take their learning further. The teacher could aid this self-selection or only provide feedback once a course of action is taken. Here the teacher is nudging and guiding but not dictating with their feedback.

2. Developing peer assessment

There is a danger that peer assessment can be at a low level so the goal is developing a more advanced level of dialogue about the effectiveness of outcomes and how taking different approaches may lead to better outcomes or more efficient practice. For instance, peer feedback allows for emotional responses in art/design/computing work – “Your work made me feel...”; “This piece is more effective because...”. For some more able pupils not all feedback is welcome, whether from peers or teachers. The idea that I can reject your feedback here is important: “Can you imagine saying to Dali that his landscapes are good but he needs to work on how he draws his clocks?”

3. Being selective with feedback

The highly skilled teacher will, at times, decide not to give feedback, at least not straight away. They are selective in their feedback. If you jump in too quickly, it can stop thinking and creativity. It can eliminate the time to process and discover. It can also be extremely annoying for the learner!

In practical terms this means letting them write in English and giving feedback later, not while they are in the flow. In a mathematical/scientific/humanities investigative setting, let them have a go and ask the pertinent question later, perhaps when they encounter difficulty. This question will be open and may nudge rather than direct the pupils. It might not be towards your intended outcome but should allow for them to take their learning forward, perhaps in unexpected directions.

In summary, this gets to the heart of the difference in feedback for more able learners compared to other pupils. While the feedback will inevitably have higher-level subject content, it should also:

- Emphasise greater responsivity for the pupil in their learning

- Involve suggestion, what ifs and hints rather than direction, and…

- Seek to excite and inspire to occasionally achieve the fantastic outcome that a more rigid approach to feedback never would. They may even write from the heart.

What does this look like in practice?

Jeavon Leonard, Vice Principal at Portswood Primary School, outlines a personal approach for more able learners he has used: “Think about when we see a puzzle in a paper/magazine – if we get stuck (as adults) we tend to flip to the answer section, not to gain the answer alone but to see how the answer was reached or fits into the clues that were given. This in turn leads to a new frame of skills to apply when you see the next problem. If this is our adult approach, why would it not be an effective approach for pupils? The feedback is in the answer. Some of the theory for this is highlighted in Why Don't Students Like School? by Daniel Willingham.”

Mel Butt, NRICH ambassador and Year 6 teacher at Tanners Brook Primary, models the writing process for her more able learners including her own second (and third) drafts which include her ‘Think Pink’ improvement and corrections. While this could be used for all pupils, Mel adds the specific requirements into the improved models for more able learners based on the assessment requirement framework for greater depth writing at the end of Key Stage 2. She comments: “I would also add something extra that is specific to the cohort of children based on the needs of their writing. We do talk about the criteria and the process encourages independence too. It's also good for them to see that even their teachers as writers need to make improvements.” The feedback therefore comes in the form of what the pupils need to see based on what they initially wrote.

Further reading

From the NACE blog:

Additional support

Dr Keith Watson is presenting a webinar on feedback on Friday 19 March 2021, as part of our Lunch & Learn series. Join the session live (with opportunity for Q&A) or purchase the recording to view in your own time and to support school/department CPD on feedback. Live and on-demand participants will also receive an accompanying information sheet, providing an overview of the research on effective feedback, frequently asked questions, and guidance on applications for more able learners. Find out more.

Tags:

assessment

differentiation

feedback

metacognition

pedagogy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ems Lord,

13 January 2021

|

NACE is proud to NACE is proud to partner with Cambridge University’s NRICH initiative, which is dedicated to creating free maths resources and activities to promote enriching, challenging maths experiences for all. In this blog post, NRICH Director Dr Ems Lord shares details of the latest free maths resources from the team, and an exclusive opportunity for NACE members…

In this blog post, I’m delighted to introduce NRICH’s new child-friendly reflection tool for nurturing successful mathematicians – part of our suite of free maths resources and activities to promote enriching, challenging mathematical experiences for all. We very much hope that you enjoy exploring it with your classes to support them to realise their potential. Such innovations are developed in partnerships with schools and teachers, and we’ll also be inviting you to work directly with our team to help design a future classroom resource intended to challenge able mathematicians (see below or click here for details of our upcoming online event for NACE members).

At NRICH, we believe that learning mathematics is about much more than simply learning topics and routines. Successful mathematicians understand the curriculum content and are fluent in mathematical skills and procedures, but they can also solve unfamiliar problems, explain their thinking and have a positive attitude about themselves as learners of mathematics. Inspired by the 'rope model' proposed by Kilpatrick et al. (2001), which draws attention to the importance of a balanced curriculum developing all five strands of mathematical proficiency equally rather than promoting some strands at the expense of others, we have developed this new model and image which uses child-friendly language so that teachers and parents can share with learners five key ingredients that characterise successful mathematicians:

- Understanding: Maths is a network of linked ideas. I can connect new mathematical thinking to what I already know and understand.

- Tools: I have a toolkit that I can choose tools from to help me solve problems. Practising using these tools helps me become a better mathematician.

- Problem solving: Problem solving is an important part of maths. I can use my understanding, skills and reasoning to help me work towards solutions.

- Reasoning: Maths is logical. I can convince myself that my thinking is correct and I can explain my reasoning to others.

- Attitude: Maths makes sense and is worth spending time on. I can enjoy maths and become better at it by persevering.

Using the tool during remote learning and beyond

This reflection tool helps learners to recognise where their mathematical strengths and weaknesses lie. Each of the maths activities in our accompanying primary and secondary features is designed to offer learners opportunities to develop their mathematical capabilities in multiple strands. We hope learners will have a go at some of the activities and then take time to reflect on their own mathematical capabilities, so that when full-time schooling returns for all they are ready to share their excitement about what they have achieved, and are eager to continue on their mathematical journeys.

At NRICH, we believe that following the current period of remote learning, success in settling back into schools will be aided by recognising and acknowledging the mathematical learning that has been achieved at home, and encouraging learners to reflect on how they see themselves as mathematicians. It may be that some learners will not recognise the value of what they have achieved while they have been out of the classroom, because what they have been doing at home may be quite different from what they usually do in school. We want learners to appreciate that there are many ways to demonstrate their mathematical capabilities, and to recognise the ways in which they behave mathematically. By inviting children and students to assess their mathematical progress on a broad range of measures, we hope to change the narrative to recognise what learners have achieved, rather than focusing on what they have missed.

Get involved….

As the current period of remote learning continues, we’re continuing to develop new free maths resources, and we always value input from teachers. On 3 February 2021, the NRICH team is hosting an online meetup for NACE members during which we’ll share an exciting new classroom resource, currently under development, intended to challenge able mathematicians. The session will involve an opportunity to explore this new resource and share your insights to help inform its future development. We look forward to working with you. Details and booking.

Very best wishes for 2021 – the NRICH team.

Ref: Kilpatrick, J., Swafford, J. and Findell, F. (eds) (2001) Adding It Up: Helping Children Learn Mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee: National Research Council.

Tags:

confidence

free resources

lockdown

maths

metacognition

mindset

motivation

remote learning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

17 November 2020

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Associate and co-author of NACE’s new publication “Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”.

When you’re planning a lesson, are your first thoughts about content, resources and activities, or do you begin by thinking about learning and cognitive challenge? How often do you consider lessons from the viewpoint of your more able pupils? Highly able pupils often seek out cognitively challenging work and can become distressed or disengaged if they are set tasks which are constantly too easy.

NACE’s new research publication, “ Cognitive challenge: principles into practice”, marks the first phase in our “Making Space for Able Learners” project. Developed in partnership with NACE Challenge Award-accredited schools, the research examines the impact of cognitive challenge in current school practice against a backdrop of relevant research. What do we mean by ‘cognitive challenge’?

Cognitive challenge can be summarised as an approach to curriculum and pedagogy which focuses on optimising the engagement, learning and achievement of highly able children. The term is used by NACE to describe how learners become able to understand and form complex and abstract ideas and solve problems. Cognitive challenge prompts and stimulates extended and strategic thinking, as well as analytical and evaluative processes.

To provide highly able pupils with the degree of challenge that will allow them to flourish, we need to build our planning and practice on a solid foundation.

This involves understanding both the nature of our pupils as learners and the learning opportunities we’re providing. When we use “challenge” as a routine, learning will be extended at specific times on specific topics – which has useful but limited benefit. However, by strategically building cognitive challenge into your teaching, pupils’ learning expertise, their appetite for learning and their wellbeing will all improve.

What does this look like in practice?

The research identified three core areas:

1. Design and management of cognitively challenging learning opportunities

In the most successful “cognitive challenge” schools, leaders have a clear vision and ambition for pupils, which explicitly reflects an understanding of teaching more able pupils in different contexts and the wider benefits of this for all pupils. This vision is implemented consistently across the school. All teachers engage with the culture and promote it in their own classrooms, involving pupils in their own learning. When you walk into any classroom in the school, pupils are working to the same model and expectation, with a shared understanding of what they need to do.

Pupils are able to take control of their learning and become more self-regulatory in their behaviours and increasingly autonomous in their learning. Through intentional and well-planned management of teaching and learning, children move from being recipients in the learning environment to effective learners who can call on the resources and challenges presented. They understand more about their own learning and develop their curiosity and creativity by extending and deepening their understanding and knowledge.

2. Rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse to support cognitive challenge

The importance of questions and questioning in effective learning is well understood, but the importance of depth and complexity of questioning is perhaps less so. When you plan purposeful, stimulating and probing questions, it gives pupils the freedom to develop their thought processes and challenge, engage and deepen their understanding. Initially the teacher may ask questions, but through modelling high-order questioning techniques, pupils in turn can ask questions which expose new ways of thinking.

This so-called “dialogic teaching” frames teaching and learning within the perspective of pupils and enhances learning by encouraging children to develop their thinking and use their understanding to support their learning. Initially, pupils might use the knowledge the teacher has given them, but when they’re shown how to use classroom discourse effectively, they’ll start to work alone, with others or with the teacher to extend their repertoire.

By using an enquiry-orientated approach, you can more actively engage children in the production of meaning and acquisition of new knowledge and your classroom will become a more interactive and language-rich learning domain where children can increase their fluency, retrieval and application of knowledge.

3. Curriculum organisation and design

How can you ensure your curriculum is organised to allow cognitive challenge for more able pupils? You need to consider:

- What is planned for the students

- What is delivered to the students

- What the students experience

Schools with a high-quality curriculum for cognitive challenge use agreed teaching approaches and a whole-school model for teaching and learning. Teachers expertly and consistently utilise key features relating to learning preferences, knowledge acquisition and memory.

Planning a curriculum for more able pupils means providing a clear direction for their learning journey. It’s necessary to think beyond individual subjects, assessment systems, pedagogy and extracurricular opportunities, and to look more deeply at the ways in which these link together for the benefit of your pupils. If teachers can understand and deliver this curriculum using their subject knowledge and pedagogical skills, and if your school can successfully make learning visible to pupils, you’ll be able to move from well-practised routines to highly successful and challenging learning experiences.

Taking it further…

If we’re going to move beyond the traditional monologic and didactic models of teaching, we need to recast the role of teacher as a facilitator of learning within a supportive learning environment. For more able pupils this can be taken a step further. If you can build cognitive challenge into your curriculum and the way you manage learning, and support this with a language-rich classroom, the entire nature of teaching and learning can change. Your highly able pupils will become increasingly autonomous and more self-reliant. They’ll become masters of their learning as they gain a deeper understanding of the subject matter. You can then extend your role even further, from learning facilitator to “learner activator”.

This blog post is based on an article originally written for and published by Teach Primary magazine – read the full version here.

Additional reading and support:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

independent learning

metacognition

mindset

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

questioning

research

student voice

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

07 September 2020

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Associate

This article was originally published in our “beyond recovery” resource pack. View the original version here.

Whilst primary schools share some of the general issues faced by all phases following the pandemic, there are specific aspects that need to considered for more able primary pupils. Research on the impact of the pandemic is still in its infancy and inevitably still speculative; while other catastrophic events such as the earthquake in Christchurch, New Zealand, are referred to, the pandemic is on a far greater scale and the full impact will take time to emerge.

What, at this stage, should primary school leaders and practitioners focus on to ensure more able learners’ needs are met?

1. Do: focus on rebuilding relationships

When pupils return to school the sense of community will need to be re-established and relationships will be central to this process. Pupils will need to feel safe and secure in school and the return to routines and robust systems will help with this. Not all more able pupils will have had the same experience both in terms of learning and home life. As always, creating a supportive learning environment will be vital.

2. Do: provide opportunities for reflection and rediscovery

All pupils need the opportunity to tell their lockdown stories and more able pupils should be encouraged to do so using their talents – whether written, artistically, through dance or other means. How best can they express their feelings over what has happened? This will allow them to come to terms with their experiences through reflection but also allow thoughts to turn positively to the future. In this sense they will be able to rediscover themselves and focus on their hopes for the future.

3. Do: use positive language

A key question (as they sing in Hamilton) is “What did I miss?” What are the gaps in learning and what is the school plan for transitioning back into learning generally and then with specific groups? We need to be careful of negative language; even terms like “catch up” and “recovery” risk suggesting we will never make up for lost time. Despite the challenge, we need to show our pupils and parents how positive we are as teachers about their future.

4. Do: find out where your pupils are

Each school will want some form of baseline assessment early in the year, whether using tests or more informal methods. Be ready to reassure more able pupils who perhaps do not achieve their normal very high scores on any testing. For more able pupils a mature dialogue should happen using pupil self-assessment alongside any data collected. Of course, each child is different and it is crucial that teachers know the individual needs of the pupils.

5. Don’t: overlook the more able

There is a danger here of the unintended consequence. The priority is likely to be given to pupils who have fallen even further below national expectation and this could lead to teachers having to divert even more time, energy and focus to these pupils at the expense of giving attention to more able pupils who may be deemed not to be a priority. More able pupils must not be neglected in this way due to assumptions that they are “fine” in terms of emotions and learning. They need to be engaged in purposeful learning and challenged as always.

6. Don’t: narrow your curriculum

Mary Myatt has previously talked of the “disciplined pursuit of doing less” and the pandemic is leading to consideration of the essential curriculum content that needs to be learned now. It may force schools to be even clearer on key learning, but we need to be careful of even greater narrowing of the curriculum, especially to test criteria. The spectre of “measurement-driven instruction” is always with us, particularly for Year 6.

7. Do: focus on building learners’ confidence

Pupils need to be settled and ready for learning, but this is often achieved through purposeful tasks. Providing more able pupils with the chance to work successfully on their favourite subjects as soon as possible can build confidence. It may be that pupils who are able across the curriculum have subjects where they fear having fallen behind more than in others. Perhaps they are very strong in both English and maths but worry about not excelling in the latter, and therefore feel concerned that they have fallen behind. It is important to gauge their feelings across the curriculum, perhaps through them RAG rating their confidence; this could then lead to individual dialogue between teacher and pupil regarding how to rebuild confidence or revisit areas where they perceive the learning is weaker. Learning is never linear; this needs to be acknowledged and pupils reassured.

8. Do: review your writing plan for the year

Teachers will be mindful of the challenges of achieving the criteria for greater depth, particularly in relation to the writing. It will be important to review the normal writing plan for the year to see that the key tasks are still appropriate and timed correctly. What does the writing journey look like throughout the year to achieve greater depth and will the normal milestones be compromised? The opportunity to experiment with their writing is essential for more able pupils, so when will this happen? Teachers in all year groups must not panic about the demanding standards needed, but instead remember they have the year to help their pupils achieve those standards, even if current attainment has dipped.

9. Do: review and adapt teaching and learning methods

The methods of teaching more able pupils will also have to be considered in the changed learning environment. Collaborative group work may be more challenging with pupils often sitting in rows and also having less close proximity to their teacher. A group of more able pupils crouched around sugar paper designing the best science experiment since the days of Newton may not currently be possible. But dialogue remains vital and time still needs to be made for it despite restrictions on classroom operations.

10. Do: remain optimistic and ambitious

We must remain optimistic for our more able pupils. We must not shy away from the opportunities to go beyond the curriculum to encourage and develop talents. More able pupils need to have the space to show themselves at their best. The primary curriculum provides so many opportunities for more able pupils to push the boundaries in the learning beyond the narrow confines of subject areas. This can be energising. The London School of Music and Dramatic Arts (LAMDA) proudly declares its students to be:

- Creators

- Innovators

- Collaborators

- Storytellers

- Engineers

- Artists

- Actors

We can also add athletes and many more to this list. More able pupils need to develop their metacognition and seeing themselves in some of these roles can inspire and motivate them. Remember though, creativity can’t be taught in a vacuum. It needs content so that the creativity can be encouraged.

Given that the “recovery curriculum” may spend a lot of time re-establishing a mental health equilibrium and helping those with large gaps in knowledge to “catch up”, it may be that those more able pupils who are ready for it can be given license by teachers to experiment more with the curriculum, have more independence and get to apply their learning more widely.

Not merely recovering, but rebounding and reigniting with energy, vigour and a celebration of talents.

Join the conversation: NACE member meetup, 15 September 2020

Join primary leaders and practitioners from across the country on 15 September for an online NACE member meetup exploring approaches to the recovery curriculum and beyond. The session will open with a presentation from NACE Associate Dr Keith Watson, followed by a chance to share approaches and ideas with peers, reflecting on some of the challenges and opportunities outlined above. Find out more and book your place.

Not yet a NACE member? Starting at just £95 +VAT and covering all staff in your school, NACE membership offers year-round access to exclusive resources and expert guidance, flexible CPD and networking opportunities. Membership also available for SCITTs, TSAs, trusts and clusters. Learn more and join today.

Tags:

assessment

confidence

curriculum

feedback

KS1

KS2

leadership

lockdown

metacognition

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Christabel Shepherd,

11 June 2020

|

Christabel Shepherd, NACE Associate and Trustee, and Executive Headteacher of Bradford’s Copthorne and Holybrook Primary Schools

Over the past few months, I have learnt a great deal about myself and, more importantly, about the conditions which are central to the effective education of the children in our schools.

In the two primary schools that I lead, home-learning during this crisis has taken two forms: printed packs of differentiated work for the core and wider curriculum (a mixture of practise, retrieval and application, as well as some new learning); and remote learning via the various sites and activities to which we have directed children (these include Mathletics, Times Tables Rockstars, White Rose Maths Hub, Accelerated Reader etc.). All of this has been supported with regular telephone check-ins with pupils and their parents/carers. The results in terms of pupil engagement have been mixed and, in turn, the impact on pupil progress is difficult to measure.

All good teachers know their children. They can spot immediately when a child has “zoned out”; one whose stress levels are increasing because they clearly don’t understand; the more able learner who is afraid to put pen to paper for fear of the work being incorrect or imperfect; or the student who is frustrated or bored due to insufficient challenge.

When children are at home, we are not there to pick up on these signals and support them appropriately, and it is not easy to spot these signs on a computer screen. Without this, it is more difficult to identify misconceptions and address them effectively and before they become ingrained; it is nigh on impossible to remind children to think back to the strategies they have been taught in order to choose the most effective one or to think about which “learning muscles” they will need to use for a task; it is much harder to encourage children to attempt a challenge and face possible failure without the culture of supported risk that we have so skilfully developed in our classrooms. Never has the need for that human interaction between teachers and pupils been so stark.

So, what can we do now to mitigate this and contingency plan for the future?

Metacognition and self-regulation

For months prior to the COVID-19 crisis, metacognition and self-regulation strategies had started to become a key focus for many schools. Much of what many excellent teachers already do by default has been given a name and its importance highlighted by the findings of evidence-based research. This has been widely shared through, for example, the work of the EEF, with more and more teachers beginning to see and understand the benefits of building these strategies into their everyday work.

Had this been going on for longer and such learning behaviours been entrenched in our children, I feel that the negative effects of lockdown would have been lessened. As it is, I feel that much more work needs to be done in this area. Many of our learners – especially in primary schools – are only at the start of their “learning how to learn” journey, so do not yet understand or have embedded the key metacognitive or self-regulation skills, nor in turn the levels of intrinsic motivation to enable them deal effectively with home learning. Whereas at school, we would have been praising children for thinking about and then using appropriate strategies, there is concern that – in many homes – children will be being praised purely for task completion rather than the way it was approached and their metacognitive strategies.

This has strengthened my view that the need for children to be taught metacognitive and self-regulation strategies should be made an even higher priority. By the way, I’m not talking about special “learning how to learn” slots in the timetable; I’m talking about those strategies being central to our pedagogy in every lesson. Although many teachers do this naturally, I believe that we must all make a conscious decision to do this, directly teaching and modelling those learning behaviours through our own practice and daily interactions.