Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By James Croxton-Cayzer,

26 March 2025

|

Walton Priory Middle School’s James Croxton-Cayzer shares his top tips for ensuring practical science lessons get students thinking as well as doing.

"Sir, are we doing a practical today?"

If you teach science, you probably hear this question at least once a lesson. Pupils love practical work, but how often do we stop and ask ourselves: are they really learning from it? Are practicals just a fun way to prove a theory, or can they be something deeper – something that engages students intellectually as well as physically?

I was recently asked to speak at a NACE member meetup about how we at Walton Priory Middle School ensure that practicals are not just hands-on, but minds-on as well. Here’s how we approach it.

1. Don’t just do a practical: know why

Before anything else, ask yourself: What do I want my pupils to learn? Every practical should have a clear learning goal, whether that’s substantive knowledge (e.g. learning about the planets) or disciplinary knowledge (e.g. “How are we going to find out the RPM of a propeller?”).

I used to assume that if pupils were engaged, they were learning. But engagement isn’t the same as deep thinking. By clearly defining why we are doing a practical and keeping cognitive overload in check, pupils can focus on the right aspects of the lesson.

2. Give them a puzzle to solve

Rather than handing over all the information at once, I break lessons into two parts:

- Knowledge I am going to give them

- Knowledge I want them to discover for themselves

Children love discovery. Instead of telling them everything, create opportunities for them to piece it together themselves. If you’re like I was, you might worry about withholding information in case they never figure it out. But I’ve found that knowledge earned is usually better retained and understood than knowledge simply given.

For example, when teaching voltage in Year 6, I might tell them that increasing voltage will increase the speed of a motor (since there’s little mystery there). But I won’t tell them how to measure the speed of the motor. Instead, I challenge them: “What methods could we use to measure the speed of a fan?” This immediately shifts their thinking from passive reception to active problem-solving.

3. Hook them with a story

While linking science to real-world applications is common practice, storytelling as a teaching tool is often overlooked. A compelling story can make abstract scientific concepts feel personal and meaningful.

For example, in our Year 5 Solar System topic, I frame the lessons as a journey where alien explorers (who conveniently share my students' names – weird that…) must learn all they can about our planet and surroundings. In our Properties of Materials topic, I create audiologs for each lesson of a ship’s journey – except there’s a saboteur on board! Each lesson, the rogue does something that requires students to investigate different properties to solve the problem. Will they ever find out who did it? Who knows! But they are certainly engaged and thinking about the science.

4. Use partial information to encourage scientific thinking

One of the most powerful ways to keep students engaged is to avoid giving them everything upfront. Instead, drip-feed key information and let them work out the missing pieces.

For example, instead of just listing the planets, I provide partial information – snippets of data they must organise themselves to determine planetary order. This encourages effortful retrieval and intellectual engagement, rather than passive memorisation.

Returning to our Year 6 voltage lesson, I ask: “How can we prove that?” Some students count propeller rotations manually. Others try using a strobe light or a slow-motion camera. One of my class recently attached a lollipop stick to the fan and tried to count the clicks on a piece of paper – a great idea, but the clicks were too fast! So I turned it back on them: “How do we solve this?”

- Record the sound? Great!

- Slow it down? Super!

- Put the sound file in Audacity and count the visualised sound wave for two seconds, then multiply by thirty? Amazing!

The key is that they think like scientists – testing, adapting, and refining their approach.

5. Keep everyone engaged

Minds-on practicals require careful structuring. Not all students will approach a task in the same way, so scaffolding and adaptive teaching are key:

- Structured worksheets help those who struggle with open-ended tasks.

- Flexible questioning allows you to stretch more able learners without overwhelming others.

- Pre-discussion before practicals ensures students understand the why as well as the how.

All students, including those with additional needs, should feel part of the investigation. Clear step-by-step instructions, visual aids, and breaking down the task into smaller chunks make a big difference.

Even with the best planning, some students will struggle. Here’s what I do:

- Encourage peer teaching. Can a more confident pupil explain the method?

- Break it down even further. Can we isolate just one variable to focus on?

- Provide alternative ways to engage. If a pupil is overwhelmed, can they observe and record data instead? Once they feel comfortable, they may ask to take on a more active role.

- Reframe the challenge. Instead of “You’re wrong,” or “That won’t work,” ask, “What made you think that?” This builds resilience and scientific thinking.

Key takeaways

- Make sure every practical has a clear learning goal.

- Give pupils a reason to investigate, not just instructions to follow.

- Use partial information to make them think like scientists.

- Ensure adaptive teaching so all pupils can access the learning.

- If pupils struggle, break it down further or reframe the challenge.

Final thought: hands-on, minds-on science

Science should be a subject of curiosity, not compliance. When we shift practicals from tick-box activities to genuine investigations, students become scientists – not just science learners.

By ensuring every practical is intellectually engaging as well as physically interactive, we help pupils develop not just knowledge, but scientific thinking. And that’s the ultimate goal: to create independent, curious learners who don’t just ask, “Are we doing a practical?”, but “Can we investigate this further?”

Related reading and resources:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

KS2

pedagogy

science

sciencepedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Charlotte Newman,

03 February 2025

|

Charlotte Newman shares five approaches to challenge learners in secondary school religious education (RE).

I want to start off by sharing my context with you as I believe this is important in what I have found works well in my school. I am a Head of Religious Education in a secondary school in Cambridgeshire. We are the largest school in the county and as a result we are truly comprehensive with a wide range of student abilities and backgrounds. At KS3, our classes are mixed ability and therefore, it can sometimes be difficult to stretch and challenge the most able when there may be other students in the group that need more support. At KS4, we set by ability with English, taking into account students’ target grades and KS3 data.

1. Teach to the top (and beyond!)

At KS3, we always aim to teach to the top and scaffold for those students who require more support. This ensures that every student in the class is challenged. Regular opportunities are built into the lessons to extend students’ thinking. This does not simply mean additional tasks, as this is something our students often get frustrated with – that ‘challenge’ equals ‘do more’. Instead, we will ask them to research something from the key stage above. For example, when teaching about the Four Noble Truths in Buddhism I might ask more able students to research the idea of dependent arising to better understand the Buddhist philosophy. At KS4, when teaching about Jesus’ resurrection to sets 1 and 2, I will bring in the views of Rudolf Bultmann and N.T. Wright on the idea of a metaphorical versus historical resurrection from KS5.

To ensure all teachers across the department are doing this effectively, we have spent CPD time mapping our KS3 against our GCSE specification to highlight the links we can make. We have done the same between our GCSE and A Level specifications. This has been particularly useful for those teachers who do not teach KS5, to increase their subject knowledge in order to stretch high ability students.

2. Encourage deep analytical thinking

In our school, we have employed PiXL ‘Thinking Harder’ strategies. These ensure students are showing their understanding of our topic by having to analyse the knowledge they have learnt. For example: which of a set of factors (Paul’s missionary journeys, martyrs, the Nicene Creed, Constantine) contributed most to the development of the early Church? They may order these and have to justify their choices.

We can also do this through questioning during philosophical debates to get students articulating their thoughts in a sophisticated argument. Examples include: “Why might that be the case?”; “Why is that significant?”; “What evidence do you have to support that view?”; “Can you add to what X just said?”

Additionally, it is important to ensure that students have the opportunity to engage with primary religious texts such as the Qur’an, as well as those from different scholars, such as Descartes’ Meditations. This enables them to develop their hermeneutical skills to really understand the text and its context, compare interpretations/perspectives of it and critically analyse it.

3. Allow opportunities for multidisciplinary connections

Religious education is a multidisciplinary subject. The Ofsted RE Review (2021) promotes “ways of knowing”, that students should understand how they know, through the disciplines of Theology, Philosophy and Social Sciences. You could arguably add others too: Psychology, History, Anthropology, etc.

When developing an enquiry question for a scheme of work, you may have in mind a particular discipline you wish the students to approach it from, for example exploring “What does it mean to be chosen by God?” using a theological method/tools to study the question from the perspective of Judaism. However, in order to stretch the most able students it would be fantastic if you gave them opportunities to think about this from a different ‘lens’. How might a Christian/Muslim approach this question? What would a philosophical/social scientist approach to this question look like?

4. Facilitate independent research projects

I currently run the NATRE Cambridgeshire RE Network Hub and so I regularly have the opportunity to meet up with other teachers/schools in my region. I was recently involved in a curriculum audit with other secondary teachers and I loved a scheme of work employed by one of my colleagues. Prior to starting the GCSE course, students are given the chance to choose a topic of interest to them within RE to conduct independent research and eventually present their findings. They are given a framework and some suggested ideas/resources to guide them as well as different ways in which they could present their research. This is a fantastic idea to stretch the most able as there is so much scope with this student-led project.

In my colleague’s school, all students have access to a handheld device, therefore IT is easily accessible to support this work. Teachers can easily share documents and links to students this way too. Unfortunately, this is not the case in my context and so wouldn’t be feasible, but I am in the process of thinking about how we could do something similar that works for us.

5. Promote independent learning outside of the classroom

In RE, we have the privilege of being able to teach about many real-world issues and ethical debates that students find fascinating. As a result, they often want to explore these further in their own time. Therefore, in my school we have compiled ‘Independent Study’ materials for each unit of both the GCSE and A Level courses.

At GCSE, we have compiled booklets where we suggest something to read, something to watch something to listen to, and something to research. These have enabled us to introduce A Level thinkers into the course and engage students with high-level thinking through The RE Podcast or Panspycast, for example. This is key as it piques students’ curiosity and promotes a real love of the subject.

At A Level, we provide students with university lectures (the University of Chester is great for this for RE) and debates between scholars on YouTube (e.g. Richard Dawkins and Alister McGrath on the relationship between religion and science). We then expect to see evidence of this further reading/research in their exam answers and their contributions to lessons.

About the author: Charlotte Newman is a Trust Lead for Religious Studies for Archway Learning Trust. She is on the Steering Group for the National Association for Teachers of RE (NATRE) and the Oak Academy Expert Group for RE. She is also a member of Cambridgeshire SACRE and has until recently led an RE local group. She has delivered much CPD on RE nationally.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

KS3

KS4

philosophy

project-based learning

questioning

religious education

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

30 January 2025

|

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, outlines the use of “thinking booklets” to embed challenge into the early years setting.

At Alfreton Nursery School, staff believe that children need an intrinsic level of challenge to enhance learning. This challenge is not always based around adding symbols to a maths problem or introducing scientific language to the magnet explorations. An early years environment has countless opportunities for challenge and this challenge can be provided in creative ways.

Thinking booklets: invitations to think and talk

Within the nursery environment, Alfreton has created curriculum zones. These zones lend themselves to curriculum progression, whilst also providing a creative thread of enquiry which runs through all areas. Booklets can be found in each space and these booklets ask abstract questions and offer provocations for debate. Drawing on the pedagogical approach Philosophy for Children (p4c), we use these booklets to ensure classroom spaces are filled with invitations to think and talk.

Literacy booklets

Booklets within the literacy area help children to reflect on the concepts of reading and writing, whilst promoting communication, breadth of vocabulary and the skills to present and justify an opinion.

For example, within the “Big Question: Writing” booklet, staff and children can find the following questions:

- What is writing?

- If nobody could read, would we still need to write?

Alongside these and other questions, there are images of different types of writing. Musical notation, cave drawings, computer text and graffiti to name but a few. Children are empowered to discuss what their understanding of writing actually is and whether others think the same. Staff are careful not to direct conversations or present their own views. Alongside these and other questions, there are images of different types of writing. Musical notation, cave drawings, computer text and graffiti to name but a few. Children are empowered to discuss what their understanding of writing actually is and whether others think the same. Staff are careful not to direct conversations or present their own views.

Maths booklets

Maths booklets are based around all aspects of the subject: shape, size, number. . .

- If a shape doesn’t have a name, is it still a shape?

- What is time?

- If you could be a circle or a triangle, which would you choose and why?

Questions do not need to be based around developing subject knowledge, and the more abstract and creative the question, the more open to all learners the booklets become.

Children explore the questions and share views. On revisiting these questions another day, often opinions will change or become further embellished. Children become aware that listening to different points of view can influence thinking.

Creative questions

Developing the skills of abstract thought and creative thinking is a powerful gift and children enjoy presenting their theories, whilst sometimes struggling to understand that there is no right or wrong answer. For the more analytical thinkers, being asked to consider whether feelings are alive – leading to an exploration of the concept “alive” – can be highly challenging. Many children would prefer to answer, “What is two and one more?”

Alfreton Nursery School’s culture of embracing enquiry, open mindset and respect for all supports children’s levels of tolerance, whilst providing cognitive challenge and opportunities for aspirational discourse. The use of simple strategies to support challenge in the classroom ensures that challenge for all is authentically embedded into our early years practice.

Read more from Alfreton Nursery School:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

early years foundation stage

enquiry

oracy

pedagogy

philosophy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Rachel Macfarlane,

09 January 2025

|

Do academically strong pupils at your school who are on the Pupil Premium register progress as quickly and attain as highly as academically strong pupils who are not?

Do these students sometimes grasp new concepts quickly and securely in the classroom and show flair and promise in lessons, only to perform less well in exams than their more advantaged peers?

If so, what can be done to close the attainment gap?

In this series of three blog posts, Rachel Macfarlane, Lead Adviser for Underserved Learners at HFL Education, explores the reasons for the attainment gap and offers practical strategies to help close it – focusing in Part 1 on diagnosing the challenges and barriers, and in Part 2 on eliminating economic exclusion. This third instalment explores the importance of a sense of belonging and status.

Our yearning to belong is one of the most fundamental feelings we experience as humans. In psychologist Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the need to experience a sense of connection and belonging sits immediately above the need for basic necessities – food, water, warmth and personal safety.

When we experience belonging, we feel calm and safe. We become more empathetic and our mood improves. In short, as Owen Eastwood explains, belonging is “a necessary condition for human performance” (Belonging, 2021:26).

Learners from less economically advantaged backgrounds than their peers often feel that they don’t fit in and have a low sense of self-worth, regardless of their academic strength. Painfully aware of what they lack compared to others, they can disappear into the shadows, consciously or subconsciously making themselves invisible. They may not volunteer to read or answer questions in class. Or audition for a part in the school play or choir. Or sign up for leadership opportunities.

They may lack the respect, rank and position that is afforded by fitting comfortably into the ‘in group’: identifying with and operating within the dominant culture, possessing the latest designer gear, phone and other material goods, being at the centre of social media groups and activity and connecting effortlessly, through lived experiences and lifestyle, with peers who hold social power and are seen as leaders and role models.

Pupils who are academically strong but who lack status are likely to be fragile and nervous learners, finding it harder to work in teams, to trust others and to accept feedback. Their energy and focus can be sapped by the trauma of navigating social situations, they are prone to feel the weight of external scrutiny and judgement, and all of that will detract from their ability to perform at their best.

The good news is that, as educators, we have amazing powers to convey a sense of belonging and status.

Ten top tips to build learners’ sense of belonging and status

The following simple behaviours convey the message that the educator cares about, is invested in, notices and respects the learner; that they have belief in their potential and want to give their discretionary effort to them.

- Welcome them to the class, ensuring that you make eye contact, address them by name and give them a smile – establishing your positive relationship and helping them feel noticed, valued and safe in the learning environment.

- Go out of your way to find opportunities to give them responsibilities or assign a role to them, making it clear to them the skills and/or knowledge they possess that make(s) them perfect for the job.

- Reserve a place for them at clubs and ensure they are well inducted into enrichment opportunities.

- Arrange groupings for activities to ensure they have supportive peers to work with.

- Invite them to contribute to discussions, to read and to give their opinions. Don’t allow confident learners to dominate the discussion (learners with high status talk more!) and don’t ask for volunteers to read (students with low status are unlikely to volunteer).

- Show respect for their opinions and defer to them for advice. e.g. “So, I’m wondering what might be the best way to go about this. Martha, what do you think?” “That’s a good point, Nitin. I hadn’t thought of that. Thank you!”

- Make a point of telling them you think they should put themselves forward for opportunities (e.g. to go to a football trial, audition for the show, apply to be a prefect) and provide support (e.g. with writing an application or practising a speech).

- Connect them with a champion or mentor (adult or older peer) from a similar background who has achieved success to build their self-belief.

- Secure high-status work experience placements or internships for them.

- Invite inspiring role models with similar lived experience into school or build the stories of such role models into schemes of learning and assemblies.

Finally, it is worth remembering that classism (judging a person negatively based on factors such as their home, income, occupation, speech, dialect or accent, lifestyle, dress sense, leisure activities or name) is rife in many schools, as it is in society. In schools where economically disadvantaged learners thrive and achieve impressive outcomes, classism is treated as seriously as the ‘official’ protected characteristics. In these schools, the taught curriculum and staff unconscious bias, EDI (equality, diversity and inclusion) and language training address classism directly and leaders take impactful action to eliminate any manifestations of it.

More from this series:

Plus: this year's NACE Conference will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

CEIAG

confidence

disadvantage

enrichment

higher education

mentoring

mindset

motivation

resilience

transition

underachievement

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Rachel Macfarlane,

09 January 2025

|

Do academically strong pupils at your school who are on the Pupil Premium register progress as quickly and attain as highly as academically strong pupils who are not?

Do these students sometimes grasp new concepts quickly and securely in the classroom and show flair and promise in lessons, only to perform less well in exams than their more advantaged peers?

If so, what can be done to close the attainment gap?

In this series of three blog posts, Rachel Macfarlane, Lead Adviser for Underserved Learners at HFL Education, explores the reasons for the attainment gap and offers practical strategies for supporting economically disadvantaged learners who have the potential to access high grades and assessment outcomes to excel in tests and exams.

It is estimated that almost one in three children in Britain are living in relative poverty – 700,000 more than in 2010. A significant number of these pupils will be learners who show academic flair and the capacity to acquire knowledge and skills with ease, but whose progress and outcomes are impacted by the real costs of the curriculum and the school day.

In Part 1, I reflected that learners from economically disadvantaged backgrounds often lack the abundance of social and cultural capital that their more advantaged peers have amassed, which can disadvantage them in tests and exams. Most schools work hard to build the social and cultural capital of their underserved learners, through the provision of trips and visits, speakers and visitors, extracurricular clubs and other enriching experiences. Yet such activities often have associated (sometimes hidden) costs that exclude certain students.

At HFL Education, we have been carrying out Eliminating Economic Exclusion (EEE) reviews for the past three years, examining the impact of the cost of the school day. These involve surveying pupils, parents, staff and governors, meeting with Pupil Premium (PP) eligible learners, examining key data and training staff. Reviews conducted in well over 100 primary and secondary schools have revealed that learners eligible for PP are less likely to attend extracurricular clubs and to go on curriculum visits and residentials, resulting in them missing vital learning that can impact on their exam and test performance.

Often PP eligible learners:

- Will not inform their parents of activities that have a cost, regardless of whether the school might subsidise or fund the activity;

- Will feign disinterest in opportunities that they know are unaffordable to their families;

- Will not take up fully funded enrichment opportunities due to other associated costs such as travel to a funded summer school, or the costs of camping equipment and/or specific clothing required for field work or an outward-bound activity;

- Will not stay on after school for activities because they are hungry and lack the resources to purchase a snack.

Ten top tips to help eliminate economic exclusion:

- Ensure that all staff have undertaken training to heighten their awareness of poverty and the financial pressures faced by many families in relation to the costs of the school day.

- Track sign-ups and attendance by PP eligibility at enrichment activities. Take action where you see underrepresentation.

- Contact parents directly to stress how valuable it would be for their child to attend and to explain the financial support that can be provided.

- Set up payment plans and give maximum notice to allow families to spread the costs.

- Book activity centres out of season when costs are lower.

- Use public transport rather than private coaches or plan visits to sites that are within a walkable distance.

- Ban visits to shops and food outlets to eradicate the need for spending money on trips.

- Set up virtual gallery tours and film screenings of plays and arrange for visiting theatre companies, bands and artists to come to school rather than taking the students to concert halls, theatres and galleries.

- Build up a stock of loanable equipment (wellies, coats, tents, waterproof clothing, musical instruments, sporting equipment, craft materials etc.)

- Provide free snacks for learners staying for after-school clubs.

Finally, various studies have found that pupils from economically disadvantaged backgrounds are also underrepresented in cohorts studying certain subjects, where there are significant costs of materials/tuition/coaching, notably music, PE, art and drama at KS4 and KS5.

The Education Policy Institute’s 2020 report showed that economically disadvantaged learners are 38% less likely to study music at GCSE than their more affluent classmates and that at the end of KS4 they are 20 months behind their peers. This is perhaps not surprising given the estimated cost of instrumental tuition (£8,000-15,000) involved in reaching grade 8 standard on an instrument (required to access a top A-level grade).

So pupils who are high performers in certain curriculum subjects at age 14 may not opt to continue with their studies at GCSE and beyond, unless the school is able to ensure access to all the resources they need to thrive and attain at top levels.

Three key questions to consider:

- Do you track which learners opt for each course at KS4 and KS5, ask questions and act accordingly where you see underrepresentation of PP eligible learners?

- Do you prioritise PP eligible learners for 1:1 options and advice at KS3>4, KS4>5 and KS5>higher education, to ensure that they are aiming high, pursuing their passions and aware of all the financial support available (e.g. use of bursary funding, reassurance around logistics of university student loans)?

- Do you determine, and strive to meet, the precise resource needs of each PP eligible learner?

More from this series:

Plus: this year's NACE Conference will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

disadvantage

enrichment

parents and carers

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Rachel Macfarlane,

09 January 2025

|

Do academically strong pupils at your school who are on the Pupil Premium register progress as quickly and attain as highly as academically strong pupils who are not?

Do these students sometimes grasp new concepts quickly and securely in the classroom and show flair and promise in lessons, only to perform less well in exams than their more advantaged peers?

If so, what can be done to close the attainment gap?

In this series of three blog posts, Rachel Macfarlane, Lead Adviser for Underserved Learners at HFL Education, explores the reasons for the attainment gap and offers practical strategies for supporting economically disadvantaged learners who have the potential to access high grades and assessment outcomes to excel in tests and exams.

This first post examines the challenges and barriers often faced by economically disadvantage learners and offers advice about precise diagnosis and smart identification of needs. Part 2 explores strategies for eliminating economic exclusion, while Part 3 looks at ways to build a sense of belonging and status for these learners to enhance their performance.

The problem with exams

The first point to make is that high stakes terminal tests and exams tend not to favour learners from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. These learners often lack the abundance of social and cultural capital that their more advantaged peers have amassed. This can result in a failure to recognise and connect with the cultural references frequently found in SATs and exam questions.

Students on the Pupil Premium (PP) register have a lower average attendance rate than those from more affluent backgrounds. Those living in multiple occupancy and/or crowded housing are more exposed to germs and viruses, and families in rented or local authority housing move accommodation more frequently, resulting in lost learning days. With packed, content-heavy exam syllabuses, missed lessons lead to less developed schema, less secure knowledge and less honed skills.

The families of economically disadvantaged learners are less likely to have the financial means to provide the personal tutoring, cramming and exam practice that their more advantaged peers benefit from. And if they have reduced levels of self-belief and confidence, as many students from underserved groups do, they are more likely to crumble under exam pressure and perform poorly in timed conditions.

But given the fact that terminal tests, in the form of SATs, GCSEs and A-levels, seem here to stay as the main means of assessing learners, what can school teachers and leaders do to ensure that economically disadvantaged learners who have the potential to access high grades and assessment outcomes excel academically?

Precise diagnosis of challenges and barriers

The first step is to get to the root of the problem. Schools which have closed the attainment gap tend to be skilled at diagnosing the precise challenge or barrier standing in the way of each underserved learner. Rather than treating all PP eligible learners as a homogeneous group, they are determined to understand the lived experience of each.

So, for example, rather than talking in general or vague terms about pupils on the PP register doing less well because their attendance rate is lower, they drill down to identify the precise reason for the absences of each learner whose attendance is below par. For one it might be that they are working at a paid job in the evenings and too tired to get up in time for school, for a second it might be that they don’t come to school on days when their one set of uniform is dirty or worn, for a third that they sometimes cannot afford the transport costs to get to school and for a fourth that they are being marginalised or bullied and therefore avoiding school.

Effective ways to diagnose challenges and barriers faced by economically disadvantaged learners include:

- Home visits, or meetings on site, to get to know parents/carers and to better understand any challenges they face;

- Employing a parent liaison officer to build up relationships based on trust and mutual respect with parents;

- Allocating a staff champion to each underserved learner to talk with and listen to them in order to better understand their lived experience;

- Administering a survey with well-chosen questions to elicit barriers faced;

- Completion of a barriers audit, guiding educators to drill down to identify the specific challenges faced by each learner.

Moving from barriers to solutions

Once specific barriers have been identified, it is important to ask the question: “What does this learner need in order to excel academically?” This ensures that the focus moves from the ‘disadvantage’ to the ‘solution’ and avoids any unintentional lowering of expectations of high-performance outcomes. The danger of getting stuck on describing ‘barriers’ or ‘challenges’ is that it can excuse, or lead to acceptance of, attainment gaps.

Encouraging staff to complete a simple table like the one below can assist in identifying needs and consequent actions. In this case, an audit of barriers has identified that the learner, a Year 7 pupil, has weak digital literacy as she had very limited access to a computer in the past.

| Barrier/challenge |

Details of the issue and identification of the learner’s or learners’ need(s) |

Strategies to be adopted to meet the need |

| Weak digital literacy |

Student needs to be allocated a laptop and to receive support with understanding all the relevant functions, in order to ensure she gets maximum benefit from it for class work and home learning and can confidently use it in a wide range of learning situations. |

1:1 sessions with a sixth former to familiarise the student with the range of functions. Weekly check-ins with tutor. Calls home to monitor that she is able to confidently use the laptop for all home learning tasks. |

You can read more about strategies to close the attainment gap in Rachel’s books Obstetrics For Schools (2021) and The A-Z of Diversity and Inclusion (2024), with additional support available through HFL Education.

More from this series:

Plus: this year's NACE Conference will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

disadvantage

diversity

underachievement

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By NACE,

05 December 2024

Updated: 05 December 2024

|

“Our world is at a unique juncture in history, characterised by increasingly uncertain and complex trajectories shifting at an unprecedented speed. These sociological, ecological and technological trends are changing education systems, which need to adapt. Yet education has the most transformational potential to shape just and sustainable futures.” (UNESCO, Futures of Education)

NACE welcomed the opportunity to respond to the Curriculum and Assessment Review (which closed for submissions on 22 November), based on our work with thousands of schools across all phases and sectors over the last 40 years.

Our response first emphasised the importance of an overarching, strategic vision for curriculum reform based on:

- Evidence and beliefs about the purposes of education and schooling at this point in the century;

- Knowledge of human capacities and capabilities and how they are best nurtured and realised;

- Addressing the needs of the present generation while building the skills of future generations;

- An approach that is sustainable and driven and coordinated by national policy;

- Appropriate selection of knowledge/content and teaching methodologies that are fit for purpose and flexibility in curriculum planning and implementation;

- Recognition of system and structural changes in and outside schools to support curriculum reform;

- Acknowledgement of the professional expertise and agency of educators and the importance of school-level autonomy;

- The perspectives and experiences of groups experiencing barriers to learning and opportunity (equity and inclusion).

Core foundations

NACE supports the importance of a curriculum built on core foundations which include:

- “Language capital” (wide-ranging forms of literacy and oracy) – viz evidence supporting the importance of reading, comprehension and vocabulary acquisition in successful learning and their place at the heart of the curriculum

- Numeracy and mathematical fluency

- Critical thinking and problem solving

- Emotional and physical well-being

- Metacognitive and cognitive skills

- Physical and practical skills

- An introduction to disciplinary domains (with a focus not just on content but on initiation into key concepts and processes)

The design of the curriculum needs to allow for the space and time to develop these skills as key threads throughout.

Whilst the current National Curriculum stresses the importance of developing basic literacy and numeracy skills at Key Stage 1, to open the doors to all future learning, schools continue to be pressured by the expectations of the wider curriculum/foundation subjects. This needs to be revisited to ensure that literacy, numeracy and wider skills can be securely embedded before schools expose children to a broader curriculum.

Content: knowledge and competencies

In secondary education an increasingly concept-/process-based approach to delivery of disciplinary fields should be envisaged alongside ‘knowledge-rich’ curriculum models already pervasive in many schools. Core foundation competencies and skills should continue to be developed, ensuring that learners acquire so-called ‘transformative competencies’ such as planning, reflection and evaluation. The curriculum must enshrine the ‘learning capital’ (e.g. language, cultural, social and disciplinary capital) which will enable young people to adapt to, thrive in and ultimately shape whatever the future holds.

Knowledge, skills, attitudes and values are developed interdependently. The concept of competency implies more than just the acquisition of knowledge and skills; it involves the mobilisation of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values in a range of specific contexts to meet complex demands. In practice, it is difficult to separate knowledge and skills; they develop together. Researchers have recognised how knowledge and skills are interconnected. For example, the National Research Council's report on 21st century competencies (2012) notes that “developing content knowledge provides the foundation for acquiring skills, while the skills in turn are necessary to truly learn and use the content. In other words, the skills and content knowledge are not only intertwined but also reinforce each other.”

Consideration needs to be given to breadth versus balance versus depth in curriculum design, alongside the production of guidance which articulates key and ‘threshold’ concepts and processes in subject areas. NACE training and development stresses the importance of teachers and learners understanding the concept of ‘desirable difficulty’ as this is essential in developing resilience and, therefore, supporting wellbeing. It is difficult to provide learners with appropriate levels of challenge/difficulty and time to work through these if curriculum content is over-heavy. In the later stages of schooling a greater emphasis could be placed on interdisciplinary links and advanced critical thinking competencies.

At all stages of education evidence-based approaches to pedagogy and assessment to maximise student learning should be incorporated into curriculum design. Such practices should also incorporate adaptations and recognition of different learning needs and address issues of equity and removing barriers to learning.

Summary

In schools achieving high-quality provision of challenge for all, the design of the curriculum includes planned progression and continuity for all groups of learners through key stages. Where school leaders understand the steps needed to develop deep learning, knowledge and understanding, rich content and secure skills are developed.

The Curriculum Review presents a much-needed opportunity to interrogate the purposes of curriculum and 21st century schooling, the fitness of the current National Curriculum and potential reforms needed. The review must be holistic, vision- and evidence-led, as well as recognising that a ‘national curriculum’ is only one part of the overall learning experience of children. Revised curriculum proposals and their implementation may also rely on reviewing and transforming existing school structures and systems as well as national resourcing issues to ensure more equitable access to high-quality education no matter where young people live and attend school. The proposals must also take account of ongoing teacher supply and quality issues and possible reforms to teacher education and professional development to match the aspirations of an English education system which is equitable, inclusive and one of the best in the world.

Most importantly, the new curriculum proposals must go much further than previously in trying to ensure that all young people leave school equipped to realise their ambitions for their personal and working lives, and to contribute to shaping their own and others’ destinies in a more equitable and caring society, along with the courage to face the unknown challenges which lie ahead.

Tags:

assessment

curriculum

policy

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Andy Griffith,

04 December 2024

|

Schools are tasked by Ofsted to “boost cultural capital” and to “close the disadvantage gap”. In this blog post, Andy Griffith, co-author of The Working Classroom, makes some practical suggestions for schools to adopt.

1. Explore the language around “cultural capital” and “disadvantage”

As educators we know that language is very important, so before we try to boost or close something we should think deeply about terms that are commonly referred to. What are the origins of these terms? What assumptions lie behind them? Ofsted describes cultural capital as “the best that has been thought and said”, but who decides what constitutes the “best”? Notions of best are, by definition, subjective value choices.

The phrase “best that has been thought and said”, originally coined by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, is worthy of study in itself (see below for reference). Bourdieu described embodied cultural capital as a person’s education (knowledge and intellectual skills) which provides advantage in achieving a higher social status. For Bourdieu the “game” is rigged. The game Bourdieu refers to is, of course, the game of life, of which education is a significant element.

When it comes to the term “disadvantaged”, Lee Elliott Major, Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter Professor, suggests that instead we refer to low-income families as “under-resourced”. Schools should be careful not to treat the working class as somehow inferior or as something that needs to be fixed.

Action: Ensure that staff fully understand the term “cultural capital”. Alongside this, explore “social capital” and “disadvantage”. This is best done through discussion and debate. Newspaper articles and even blogs like this one can act as a good stimulus.

2. Create a well-designed cultural curriculum

Does your school have a plan for taking students on a cultural journey? How many trips will your students go on before they leave your school? Could these experiences be incorporated into a passport of sorts?

The cultural experiences you offer will be determined by factors such as your school’s location and budget. A lot of cultural experiences can be delivered in-house in the form of external speakers, films and documentaries, or virtual reality. Others will require excursions. In either case, creating a Cultural Passport helps staff to plan experiences that complement and supplement previous experiences.

Schools should strike a balance between celebrating each community’s history and going beyond the existing community to broaden students’ horizons. Again, language is important. Does your school’s cultural curriculum explore the differences between so-called “high” and “low” culture?

No class is an island. Students of all social backgrounds should experience live theatre, visiting museums, going to art exhibitions, visiting the countryside and encountering people from cultures other than their own. Equally, every school’s cultural curriculum should celebrate working class culture. The working classes have a vibrant history of creating art, music, theatre, literature and so on, which needs to be reflected in the core curriculum.

By looking through the lens of race and gender, most schools have a more diverse offering of writers compared with when I went to school. It is right that more Black voices and more female voices are represented in the school curriculum. This opens new insights for readers, as well as providing Black and female students with more role models.

Similarly, there should be a strong emphasis on the work of working-class artists and autodidacts, no matter the social demographic of the school. Studying working-class writers such as Jimmy McGovern, Kayleigh Lewellyn, and musicians such as Terry Hall and even Dolly Parton can be inspiring. Similarly, learning about autodidacts such as Charles Dickens, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Vincent Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo can teach students that where there is a strong desire to learn, people can find a way.

Action: Ensure your school is “teaching backwards” from rich cultural experiences. Outline the experiences that will be stamped in their Cultural Passport before they leave your school.

3. Explore social capital barriers for students

One of the greatest things we can do as educators is to remove a barrier that is holding a student back. One barrier that is faced by many working-class students is lack of social capital – i.e. the limited range of occupations of their social acquaintances or network.

In 2016 I created the first of a number of Scholars Programmes in Kirkby, Merseyside. I’m proud that as well as making a positive impact on academic results at GCSE, it has raised aspirations. The programme is deliberately designed to build social capital. Over the duration of the programme (from Year 7 to 11), students have opportunities to meet and interview adults who are in careers that they aspire to. As well as work experience, the school organises Zoom interviews for students with people working in the industry that they are interested in joining. Not only do these interviews invigorate students, they create a contact that is there to be emailed for information and advice. Over time, the school has created a database of contacts who are able to offer work placements or are happy to take part in either face-to-face or virtual interviews with students. These people are friends and family members of the staff, and even friends of friends.

It is much, much harder for working class students to enter elite professions such as medicine, law and the media. The arts and the creative industries are also harder to break into. Contacts who are able to help a student to build specific industry knowledge and experience can give them a better chance of future success.

Action: Creatively utilise a database of school contacts to provide information and advice for students. Match students with professionals who can offer career advice and insights.

Reference: P. Bourdieu, Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In J. Karabel and A. H. Halsey (eds), Power and Ideology in Education (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), pp. 487–51.

The ideas and strategies in this article are contained within The Working Classroom by Matt Bromley and Andy Griffith (Crown House Publishing). More information about the book and training around its contents can be found here.

NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website. View our member offers page for details.

Plus... The NACE Conference 2025 will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

CEIAG

disadvantage

diversity

enrichment

mentoring

myths and misconceptions

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Oliver Barnes,

04 December 2024

|

Ollie Barnes is lead teacher of history and politics at Toot Hill School in Nottingham, one of the first schools to attain NACE Challenge Ambassador status. Here he shares key ingredients in the successful addition of a module on Hong Kong to the school’s history curriculum. You can read more in this article published in the Historical Association’s Teaching History journal.

When the National Security Law came into effect in Hong Kong, it had a profound and unexpected impact 6000 miles away, in Nottinghamshire’s schools. Important historical changes were in process and pupils needed to understand them. As a history department in a school with a growing cohort of Hong Kongers, it became essential to us that students came to appreciate the intimate historical links between Hong Kong and Britain and this history was largely hidden, or at least almost entirely absent, in the history curriculum.

But exploring Hong Kong gave us an opportunity to tell our students a different story, explore complex concepts and challenge them in new ways. Here I will outline the opportunities that Hong Kong can offer as part of a broad and diverse curriculum.

Image source: Unsplash

1. Tell a different story

In our school in Nottinghamshire, the student population is changing. Since 2020, the British National Overseas Visa has allowed hundreds of families the chance to start a new life in the UK. Migration from Hong Kong has rapidly increased. Our school now has a large Cantonese-speaking cohort, approximately 15% of the school population. The challenge this presented us with was how to create a curriculum which is reflective of our students.

Hong Kong offered us a chance to explore a new narrative of the British Empire. In textbooks, Hong Kong barely gets a mention, aside from throwaway statements like ‘Hong Kong prospered under British rule until 1997’. We wanted to challenge our students to look deeper.

We designed a learning cycle which explored the story of Hong Kong, from the Opium Wars in 1839 to the National Security Law in 2020. This challenged our students to consider their preconceptions about Hong Kong, Britain’s impact and migration.

2. Use everyday objects

To bring the story to life, we focused on everyday objects, which are commonly used by our students and could help to tell the story.

First, we considered a cup of tea. We asked why a drink might lead to war? We had already explored the Boston Tea Party, as well as British India, so students already knew part of this story, but a fresh perspective led to rich discussions about war, capitalism, intoxicants and the illegal opium trade.

Our second object was a book, specifically Mao’s Little Red Book. We used it to explore the impact of communism on China, showing how Hong Kong was able to develop separately, with a unique culture and identity.

Lastly, an umbrella. We asked: how might this get you into trouble with the police? Students came up with a range of uses that may get them arrested, before we revealed that possessing one in Hong Kong today could be seen as a criminal act. This allowed us to explore the protest movement post-handover.

At each stage of our enquiry, objects were used to drive the story, ensuring all students felt connected to the people we discussed.

Umbrella Revolution Harcourt Road View 2014 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

3. Keep it complex

In order to challenge our students, we kept it complex. They were asked to draw connections and similarities between Hong Kong and other former British colonies. We also wanted them to encounter capitalism and communism, growth and inequality. Hong Kong gave us a chance to do this in a new and fresh way.

Part of this complexity was to challenge students’ preconceptions of communism, and their assumptions about China. By exploring the Kowloon walled city, which was demolished in 1994, students could discuss the problems caused by inequality in a globalised capitalist city.

Image source: Unsplash

What next?

Our Year 9 students responded overwhelmingly positively. The student survey we conducted showed that they enjoyed learning the story and it helped them understand complex concepts.

Hong Kong offers curricula opportunities beyond the history classroom. In English, students can explore the voices of a silenced population, forced to flee or face extradition. In geography, Hong Kong offers a chance to explore urbanisation, the built environment and global trade.

Additional reading and resources

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

enquiry

history

KS3

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

11 November 2024

|

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, explores the power of metacognition in empowering young people to overcome potential barriers to achievement.

Disadvantage presents itself in different ways and has varying levels of impact on learners. It is important to remember that disadvantage is wider than children who are in receipt of pupil premium or children who have a special educational need. Disadvantage can be based around family circumstances, for example bereavement, divorce, mental health… Disadvantages can be long-term or short-term and the fluidity of disadvantage needs to be acknowledged in order for educators to remain effective and vigilant for all children, including more able learners. If we accept that disadvantage can impact any child at any time, then it is essential that we provide all children with the tools they need to navigate challenge.

More able learners are as vulnerable to the impact of disadvantage as other learners and indeed research would suggest that outcomes for more able learners are more dramatically impacted by disadvantage than outcomes for other children. A cognitive toolbox that is familiar, understood and accessible at all times, can be a highly effective support for learners when there are barriers to progress. By ensuring that all learners are taught metacognition from the beginning of their educational journey and year on year new metacognition skills are integrated, a child is empowered to maintain a trajectory for success.

How can metacognition reduce barriers to learning?

Metacognition supports children to consciously access and manipulate thinking strategies, thus enabling them to solve problems. It can allow them to remain cognitively engaged for longer, becoming emotionally dysregulated less frequently. A common language around metacognition enables learners to share strategies and access a clear point of reference, in times of vulnerability. Some more able learners can find it hard to manage emotions related to underachievement. Metacognition can help children to address both these emotional and cognitive demands.

In order for children to impact their long-term memory and fully embed metacognitive strategies, educators need to teach in many different ways. Metacognition needs to be visually reflected in the learner’s environment, supporting teachers to teach and learners to learn.

How do we do this at Alfreton Nursery School?

At Alfreton Nursery School we ensure that discourse is littered with practical examples of how conscious thinking can result in deeper understanding. Spontaneous conversations are supported by visual aids around the classroom, enabling teachers and learners to plan and reflect on thinking strategies. Children are empowered to integrate the language of metacognition as they explain their learning and strive for greater understanding.

Adults in school use metacognitive terms when talking freely to each other, exposing children to their natural use. Missed opportunities are openly shared within the teaching team, supporting future developments.

Within enrichment groups, metacognition is a transparent process of learning. Children are given metacognitive strategies at the beginning of enhancement opportunities and encouraged to reflect and evaluate at the end. Whether working indoors or outdoors, with manipulatives or abstract concepts and individually or in a group, metacognition is a vehicle through which all learners can access lesson content.

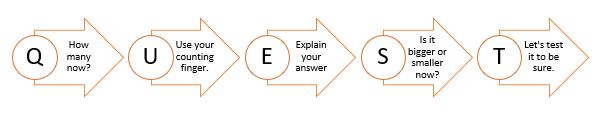

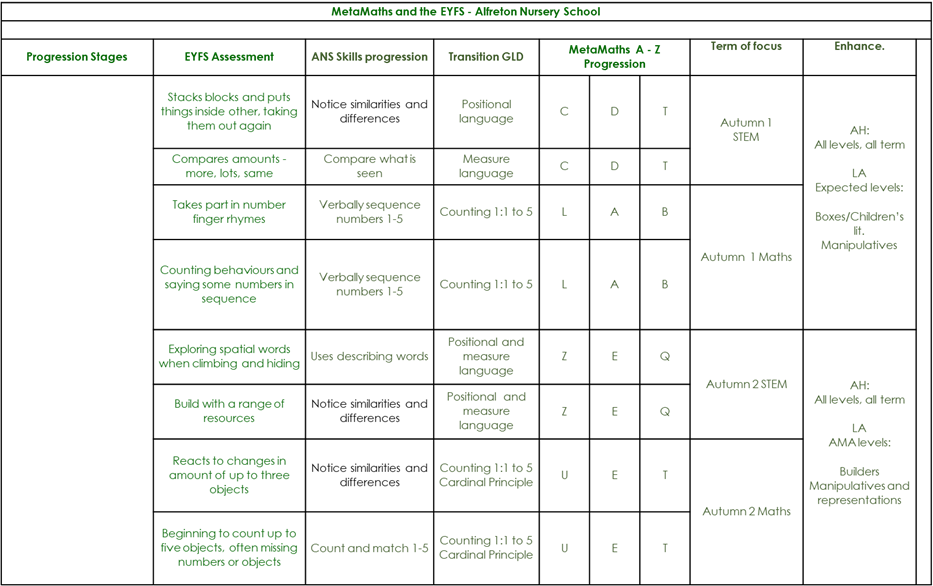

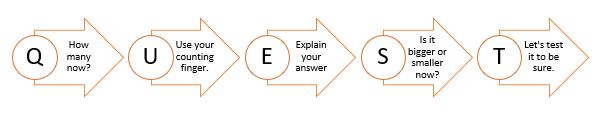

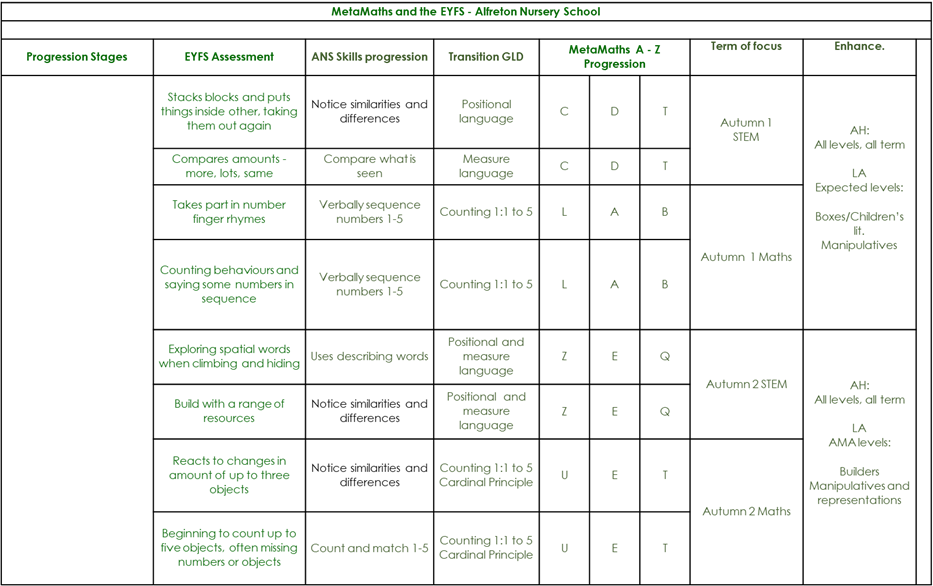

We use the ‘Thinking Moves’ metacognition framework (you can read more about this here). Creative application of this framework supports the combination of metacognition words, to make strings of thinking strategies. For example, a puppet called FRED helps children to Formulate, Respond, Explain and Divide their learning experiences. A QUEST model helps children to follow a process of Questioning, Using, Explaining, Sizing and Testing.

Metacognition supports children of all abilities, ages and backgrounds, to overcome barriers to learning. Disadvantage is thus reduced.

Moving from intent to implementation

Systems and procedures at Alfreton Nursery School serve to scaffold day to day practice and provide a backdrop of expectations and standards. In order to best serve more able children who are experiencing disadvantage, these frameworks need to be explicit in their inclusivity and flexibility. Just as every policy, plan, assessment, etc will address the needs of all learners – including those who are more able – so all these documents explicitly address how metacognition will support all learners. To ensure that visions move beyond ‘intent’ and are fully implemented, systems need to guide provision through a metacognitive lens.

Metacognition is woven into all curriculum documents. A systematic and dynamic monitoring system, which tracks the progress and attainment of all learners, ensures that children have equal focus on cognition and emotion, breaking down barriers with conscious intent.

At Alfreton Nursery School, those children who are more able and experiencing disadvantage receive a carefully constructed meta-curriculum which scaffolds their journey towards success, in whatever context that may manifest itself. Children learn within an environment where teachers can articulate, demonstrate and inculcate the power of metacognition, enabling children to be the best that they can be.

How is your school empowering and supporting young people to break down potential barriers to learning and achievement? Read more about NACE’s research focus for this academic year, and contact us to share your experiences.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

disadvantage

early years foundation stage

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

resilience

underachievement

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|