Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Helen Morgan,

01 December 2025

Updated: 01 December 2025

|

Helen Morgan, Subject Leader for Reading, English Lead Practitioner, More Able Champion & DDSL at St Michael Catholic Primary School & Nursery in Ashford, Surrey

With the ‘Year of Reading’ fast approaching, it’s a good time to re-assess the provisions in place for our children. As an English lead, questions I ask myself often revolve around the following…

- What are our children reading?

- Why do they make the choices that they do?

- In what ways can I support them?

This is especially important when it comes to children sharing what they have read, as I believe there are many effective ways to do this other than merely completing a reading record book. After I have read a great book (or a terrible one for that matter) there’s nothing I love more than discussing it with others. It was for this reason that I joined a ‘Teachers’ Reading Group’, facilitated by The Open University’s Reading for Pleasure volunteers.

The project I undertook at the end of the year involved setting up a staff book club where we read and discussed children’s books. It was very successful, in more ways than I realised it would be:

- We really enjoyed reading and discussing the texts.

- It broadened our knowledge of children’s literature.

- As staff finished reading the books, they were placed in class libraries.

- We noticed that groups of children were taking the books and reading them together, forming their own small book groups.

As the NACE lead at my school, I considered how I could use my findings to benefit more groups of children, so I started running a book club for our more able children. I adopted the Reading Gladiators programme curated by Nikki Gamble and the team at Just Imagine, which focuses on high-level discussion and eliciting creative responses to quality texts. Over the years these book clubs have been extremely popular, so we now run additional book clubs for less engaged readers and a picture book club with a focus on visual literacy.

Here are five reasons why I believe book clubs are a valuable way to foster reading for pleasure for all children, through informal, dialogic group discussion.

1) They develop critical and reflective thinking.

- Through guided discussion, children learn to justify opinions with evidence and challenge assumptions elicited from both the text and from each other.

- The discussions foster metacognition and allow children to deepen their thinking. Research has shown that this links to higher achievement.

2) They nurture social and emotional intelligence.

- Children build their skills in empathy through exploring different perspectives, including that of their peers.

- It allows children time to reflect on and enjoy what they are reading without the pressure of having to answer formal questions.

3) They foster independence and help children to make meaningful connections.

- Book clubs expose children to a wide range of texts that they might not choose independently.

- They enable leaders to read with rather than to children.

- Reading for pleasure thrives when children can relate what they read to themselves, other texts and the world, thus deepening their ideas.

4) They encourage dialogic interaction.

- Book clubs encourage children to verbalise their interpretations and listen to others’ viewpoints.

- Discussion helps them move from literal understanding to analysis and evaluation — exploring themes, author choices, and symbolism.

- Informal book talk enables children to build empathy whilst exploring different perspectives.

- Collaborative reading builds confidence, listening skills, and the ability to challenge each other’s thinking, which are key aspects of social learning.

5) They promote agency, create a community of readers and foster a love of reading.

- When children play an integral part in discussion direction, they feel ownership and autonomy.

- Book clubs shift reading from a solitary task to a social practice.

- This helps to build a community of engaged readers who are invested, curious and motivated.

References

Tags:

critical thinking

independent learning

reading

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Tom Greenwood,

26 March 2025

|

Holme Grange School's Tom Greenwood shares six steps to maximise the impact of your practical science lessons.

Science is more than just memorising facts and following instructions. True scientific thinking requires critical analysis, problem-solving, and creativity. Practical science provides the perfect platform for developing these skills, pushing students beyond basic understanding and into the realm of higher-order thinking.

Why challenge matters in science education

Practical science sits at the peak of Bloom’s revised taxonomy (Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001), requiring students not just to remember and understand but to apply, analyse, evaluate, and create. These skills are essential for developing scientifically literate individuals who can tackle real-world problems with confidence and insight.

Steps to maximizing the impact of practical science

To truly challenge students and develop their higher-order thinking, practical science lessons must be carefully structured. Here’s how:

Step 1: Solve real-world problems

Practical science activities should be grounded in real-world applications. When students see the relevance of their experiments, their engagement increases. For example, testing water purity or designing a simple renewable energy system connects scientific principles to everyday life.

Step 2: Get the groups right

Collaboration is key in scientific exploration. Thoughtful grouping of students – pairing diverse skill levels or encouraging peer mentoring – can enhance problem-solving and communication skills.

Step 3: Maintain a relentless focus on variables

From Year 5 to Year 11, students should develop a keen understanding of variables. This means recognising independent, dependent, and control variables and understanding their importance in experimental design.

Step 4a: Leave out a variable

By removing a key variable from an experiment, students are forced to think critically about the design and purpose of their investigation. They must determine what’s missing and how it affects the outcome.

Step 4b: Omit the plan

Instead of providing a step-by-step method, challenge students to devise their own experimental plans. This pushes them to apply their understanding of scientific concepts and fosters creativity in problem-solving.

Step 5: Analyse data like a pro

Teaching students to collect, visualise, and interpret data is crucial. Using AI tools to display class results can make data analysis more engaging and accessible. By linking their findings back to the research question, students develop deeper analytical skills.

Step 6: When practicals go wrong (or right!)

Failure is an integral part of scientific discovery. Encouraging students to reflect on unexpected results – whether positive or negative – teaches resilience, adaptability, and critical thinking.

Bonus step: Harness the power of a Science Challenge Club

A Science Challenge Club can provide a platform for students to explore scientific questions beyond the curriculum. Such clubs foster independent thinking and offer opportunities for students to work on long-term investigative projects, deepening their understanding and enthusiasm for science.

Final thoughts: why practical science is essential

Engaging students in hands-on science doesn’t just make lessons more interesting – it equips them with crucial skills:

- Critical thinking: encourages deeper questioning and problem-solving.

- Collaboration: strengthens teamwork and communication.

- Real-world problem solving: helps students connect theory to practice.

As educators, we can design activities that challenge high-achieving students, encourage independent experiment design, and foster strong analytical skills. By doing so, we prepare students not only for exams but for real-world scientific challenges.

The future of science lies in the hands of the next generation. Let’s ensure they have the skills to think critically, innovate boldly, and explore fearlessly.

Related reading and resources:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

collaboration

critical thinking

pedagogy

problem-solving

resilience

science

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

30 January 2025

|

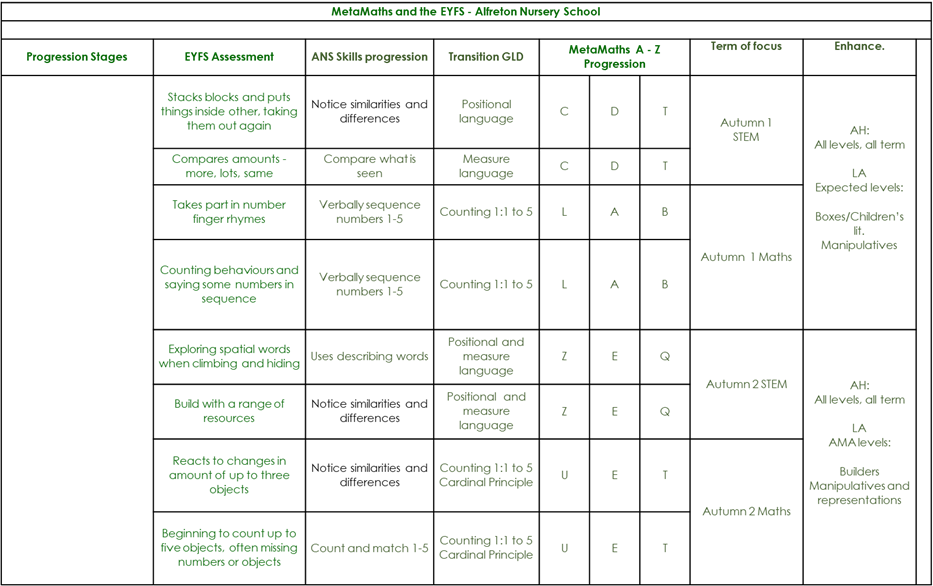

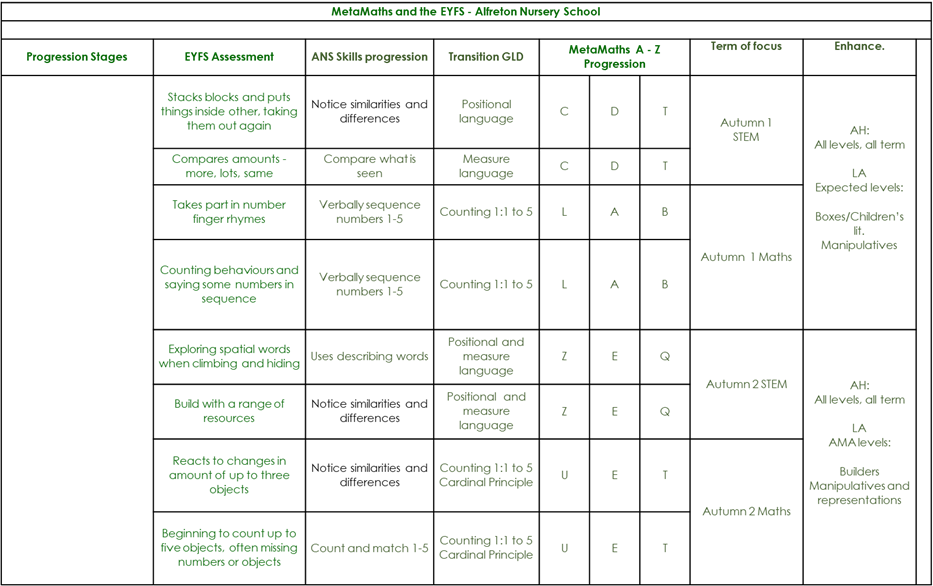

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, outlines the use of “thinking booklets” to embed challenge into the early years setting.

At Alfreton Nursery School, staff believe that children need an intrinsic level of challenge to enhance learning. This challenge is not always based around adding symbols to a maths problem or introducing scientific language to the magnet explorations. An early years environment has countless opportunities for challenge and this challenge can be provided in creative ways.

Thinking booklets: invitations to think and talk

Within the nursery environment, Alfreton has created curriculum zones. These zones lend themselves to curriculum progression, whilst also providing a creative thread of enquiry which runs through all areas. Booklets can be found in each space and these booklets ask abstract questions and offer provocations for debate. Drawing on the pedagogical approach Philosophy for Children (p4c), we use these booklets to ensure classroom spaces are filled with invitations to think and talk.

Literacy booklets

Booklets within the literacy area help children to reflect on the concepts of reading and writing, whilst promoting communication, breadth of vocabulary and the skills to present and justify an opinion.

For example, within the “Big Question: Writing” booklet, staff and children can find the following questions:

- What is writing?

- If nobody could read, would we still need to write?

Alongside these and other questions, there are images of different types of writing. Musical notation, cave drawings, computer text and graffiti to name but a few. Children are empowered to discuss what their understanding of writing actually is and whether others think the same. Staff are careful not to direct conversations or present their own views. Alongside these and other questions, there are images of different types of writing. Musical notation, cave drawings, computer text and graffiti to name but a few. Children are empowered to discuss what their understanding of writing actually is and whether others think the same. Staff are careful not to direct conversations or present their own views.

Maths booklets

Maths booklets are based around all aspects of the subject: shape, size, number. . .

- If a shape doesn’t have a name, is it still a shape?

- What is time?

- If you could be a circle or a triangle, which would you choose and why?

Questions do not need to be based around developing subject knowledge, and the more abstract and creative the question, the more open to all learners the booklets become.

Children explore the questions and share views. On revisiting these questions another day, often opinions will change or become further embellished. Children become aware that listening to different points of view can influence thinking.

Creative questions

Developing the skills of abstract thought and creative thinking is a powerful gift and children enjoy presenting their theories, whilst sometimes struggling to understand that there is no right or wrong answer. For the more analytical thinkers, being asked to consider whether feelings are alive – leading to an exploration of the concept “alive” – can be highly challenging. Many children would prefer to answer, “What is two and one more?”

Alfreton Nursery School’s culture of embracing enquiry, open mindset and respect for all supports children’s levels of tolerance, whilst providing cognitive challenge and opportunities for aspirational discourse. The use of simple strategies to support challenge in the classroom ensures that challenge for all is authentically embedded into our early years practice.

Read more from Alfreton Nursery School:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

early years foundation stage

enquiry

oracy

pedagogy

philosophy

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Oliver Barnes,

04 December 2024

|

Ollie Barnes is lead teacher of history and politics at Toot Hill School in Nottingham, one of the first schools to attain NACE Challenge Ambassador status. Here he shares key ingredients in the successful addition of a module on Hong Kong to the school’s history curriculum. You can read more in this article published in the Historical Association’s Teaching History journal.

When the National Security Law came into effect in Hong Kong, it had a profound and unexpected impact 6000 miles away, in Nottinghamshire’s schools. Important historical changes were in process and pupils needed to understand them. As a history department in a school with a growing cohort of Hong Kongers, it became essential to us that students came to appreciate the intimate historical links between Hong Kong and Britain and this history was largely hidden, or at least almost entirely absent, in the history curriculum.

But exploring Hong Kong gave us an opportunity to tell our students a different story, explore complex concepts and challenge them in new ways. Here I will outline the opportunities that Hong Kong can offer as part of a broad and diverse curriculum.

Image source: Unsplash

1. Tell a different story

In our school in Nottinghamshire, the student population is changing. Since 2020, the British National Overseas Visa has allowed hundreds of families the chance to start a new life in the UK. Migration from Hong Kong has rapidly increased. Our school now has a large Cantonese-speaking cohort, approximately 15% of the school population. The challenge this presented us with was how to create a curriculum which is reflective of our students.

Hong Kong offered us a chance to explore a new narrative of the British Empire. In textbooks, Hong Kong barely gets a mention, aside from throwaway statements like ‘Hong Kong prospered under British rule until 1997’. We wanted to challenge our students to look deeper.

We designed a learning cycle which explored the story of Hong Kong, from the Opium Wars in 1839 to the National Security Law in 2020. This challenged our students to consider their preconceptions about Hong Kong, Britain’s impact and migration.

2. Use everyday objects

To bring the story to life, we focused on everyday objects, which are commonly used by our students and could help to tell the story.

First, we considered a cup of tea. We asked why a drink might lead to war? We had already explored the Boston Tea Party, as well as British India, so students already knew part of this story, but a fresh perspective led to rich discussions about war, capitalism, intoxicants and the illegal opium trade.

Our second object was a book, specifically Mao’s Little Red Book. We used it to explore the impact of communism on China, showing how Hong Kong was able to develop separately, with a unique culture and identity.

Lastly, an umbrella. We asked: how might this get you into trouble with the police? Students came up with a range of uses that may get them arrested, before we revealed that possessing one in Hong Kong today could be seen as a criminal act. This allowed us to explore the protest movement post-handover.

At each stage of our enquiry, objects were used to drive the story, ensuring all students felt connected to the people we discussed.

Umbrella Revolution Harcourt Road View 2014 (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

3. Keep it complex

In order to challenge our students, we kept it complex. They were asked to draw connections and similarities between Hong Kong and other former British colonies. We also wanted them to encounter capitalism and communism, growth and inequality. Hong Kong gave us a chance to do this in a new and fresh way.

Part of this complexity was to challenge students’ preconceptions of communism, and their assumptions about China. By exploring the Kowloon walled city, which was demolished in 1994, students could discuss the problems caused by inequality in a globalised capitalist city.

Image source: Unsplash

What next?

Our Year 9 students responded overwhelmingly positively. The student survey we conducted showed that they enjoyed learning the story and it helped them understand complex concepts.

Hong Kong offers curricula opportunities beyond the history classroom. In English, students can explore the voices of a silenced population, forced to flee or face extradition. In geography, Hong Kong offers a chance to explore urbanisation, the built environment and global trade.

Additional reading and resources

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

curriculum

enquiry

history

KS3

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

11 November 2024

|

Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Alfreton Nursery School, explores the power of metacognition in empowering young people to overcome potential barriers to achievement.

Disadvantage presents itself in different ways and has varying levels of impact on learners. It is important to remember that disadvantage is wider than children who are in receipt of pupil premium or children who have a special educational need. Disadvantage can be based around family circumstances, for example bereavement, divorce, mental health… Disadvantages can be long-term or short-term and the fluidity of disadvantage needs to be acknowledged in order for educators to remain effective and vigilant for all children, including more able learners. If we accept that disadvantage can impact any child at any time, then it is essential that we provide all children with the tools they need to navigate challenge.

More able learners are as vulnerable to the impact of disadvantage as other learners and indeed research would suggest that outcomes for more able learners are more dramatically impacted by disadvantage than outcomes for other children. A cognitive toolbox that is familiar, understood and accessible at all times, can be a highly effective support for learners when there are barriers to progress. By ensuring that all learners are taught metacognition from the beginning of their educational journey and year on year new metacognition skills are integrated, a child is empowered to maintain a trajectory for success.

How can metacognition reduce barriers to learning?

Metacognition supports children to consciously access and manipulate thinking strategies, thus enabling them to solve problems. It can allow them to remain cognitively engaged for longer, becoming emotionally dysregulated less frequently. A common language around metacognition enables learners to share strategies and access a clear point of reference, in times of vulnerability. Some more able learners can find it hard to manage emotions related to underachievement. Metacognition can help children to address both these emotional and cognitive demands.

In order for children to impact their long-term memory and fully embed metacognitive strategies, educators need to teach in many different ways. Metacognition needs to be visually reflected in the learner’s environment, supporting teachers to teach and learners to learn.

How do we do this at Alfreton Nursery School?

At Alfreton Nursery School we ensure that discourse is littered with practical examples of how conscious thinking can result in deeper understanding. Spontaneous conversations are supported by visual aids around the classroom, enabling teachers and learners to plan and reflect on thinking strategies. Children are empowered to integrate the language of metacognition as they explain their learning and strive for greater understanding.

Adults in school use metacognitive terms when talking freely to each other, exposing children to their natural use. Missed opportunities are openly shared within the teaching team, supporting future developments.

Within enrichment groups, metacognition is a transparent process of learning. Children are given metacognitive strategies at the beginning of enhancement opportunities and encouraged to reflect and evaluate at the end. Whether working indoors or outdoors, with manipulatives or abstract concepts and individually or in a group, metacognition is a vehicle through which all learners can access lesson content.

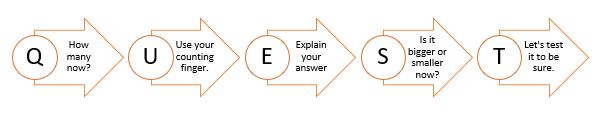

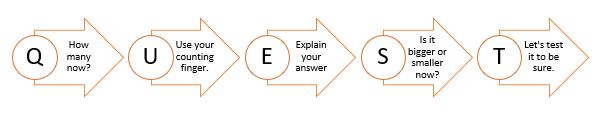

We use the ‘Thinking Moves’ metacognition framework (you can read more about this here). Creative application of this framework supports the combination of metacognition words, to make strings of thinking strategies. For example, a puppet called FRED helps children to Formulate, Respond, Explain and Divide their learning experiences. A QUEST model helps children to follow a process of Questioning, Using, Explaining, Sizing and Testing.

Metacognition supports children of all abilities, ages and backgrounds, to overcome barriers to learning. Disadvantage is thus reduced.

Moving from intent to implementation

Systems and procedures at Alfreton Nursery School serve to scaffold day to day practice and provide a backdrop of expectations and standards. In order to best serve more able children who are experiencing disadvantage, these frameworks need to be explicit in their inclusivity and flexibility. Just as every policy, plan, assessment, etc will address the needs of all learners – including those who are more able – so all these documents explicitly address how metacognition will support all learners. To ensure that visions move beyond ‘intent’ and are fully implemented, systems need to guide provision through a metacognitive lens.

Metacognition is woven into all curriculum documents. A systematic and dynamic monitoring system, which tracks the progress and attainment of all learners, ensures that children have equal focus on cognition and emotion, breaking down barriers with conscious intent.

At Alfreton Nursery School, those children who are more able and experiencing disadvantage receive a carefully constructed meta-curriculum which scaffolds their journey towards success, in whatever context that may manifest itself. Children learn within an environment where teachers can articulate, demonstrate and inculcate the power of metacognition, enabling children to be the best that they can be.

How is your school empowering and supporting young people to break down potential barriers to learning and achievement? Read more about NACE’s research focus for this academic year, and contact us to share your experiences.

Tags:

cognitive challenge

critical thinking

disadvantage

early years foundation stage

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

problem-solving

resilience

underachievement

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

17 April 2023

Updated: 17 April 2023

|

NACE Associate Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Challenge Award-accredited Alfreton Nursery School, explains why and how environmental education has become an integral part of provision in her early years setting.

1. What’s the intent?

The ethics of teaching children of all ages about sustainability is clear. However, teaching such big concepts with such small children needs careful thought. The intention at Alfreton Nursery School is to stimulate an enquiring mind and to nurture children to believe in a solutions-based future.

Exposure to climate change from an adult perspective is dripping into our children’s awareness all the time. At Alfreton Nursery School we believe it is so important to take the current climate and give children a voice and a role within it. The invincibility of the early years mindset has been harnessed, with playful impact.

2. How do I implement environmental education with four-year-olds?

Environment

Just as an effective school environment supports children’s mathematical, creative (etc) development, so our environment at Alfreton is used to educate children on the value of nature. The resources we use are as ethically made and resourced as possible. We use recycled materials and recycled furniture, and lights are on sensors to reduce power consumption.

Like many schools, we have adapted our environment to work with the needs of the planet, and at Alfreton we make our choices explicit for the children. We talk about why the lights don’t stay on all the time, why we have a bicycle parking area in the carpark and why we are sitting on wooden logs, rather than plastic chairs. Our indoor spaces are sprinkled with beautiful large plants, adding to air quality, aesthetics and a sense of nature being a part of us, rather than separate. Incidental conversations about the interdependence of life on our planet feed into daily interactions.

Our biophilic approach to the school environment supports wellbeing and mental health for all, as well as supporting the education of our future generations.

Continuous provision and enhancements

Within continuous provision, resources are carefully selected to enhance understanding of materials and environmental impact. We have not discarded all plastic resources and sent them to landfill. Instead we have integrated them with newer ethical purchasing and take the opportunity to talk and debate with children. Real food is used for baking and food education, not for role play. Taking a balanced approach to the use of food in education feels like the respectful thing to do, as many of our families exist in a climate of poverty.

Larger concepts around deforestation, climate change and pollution are taught in many ways. Our provision for more able learners is one way we expand children’s understanding. In the Aspiration Group children are taught about the world in which they live and supported to understand their responsibilities. We look at ecosystems and explore human impact, whilst finding collaborative solutions to protect animals in their habitats. Through Forest Schools children learn the need to respect the woodlands. Story and reference literature is used to stimulate empathy and enquiry, whilst home-school partnerships further develop the connections we share with community projects to support nature.

We have an outdoor STEM Hive dedicated to environmental education. Within this space we have role play, maths, engineering, small world, science, music… but the thread which runs through this area is impact on the planet. When engaged with train play, we talk about pollution and shared transport solutions. When playing in the outdoor house we discuss where food comes from and carbon footprints. In the Philosophy for Children area we debate concepts like ‘fairness’ – for me, you, others and the planet. And on boards erected in the Hive there are images of how humans have taken the lead from nature. For example, in the engineering area there are images of manmade bridges and dams, along with images of beavers building and ants linking their bodies to bridge rivers.

3. Where will I see the impact?

Our environmental work in school has supported the progression of children across the curriculum, supporting achievements towards the following goals:

Personal, Social and Emotional Development:

- Show resilience and perseverance in the face of challenge

- Express their feelings and consider the feelings of others

Understanding the World:

- Begin to understand the need to respect and care for the natural environment and all living things

- Explore the natural world around them

- Recognise some environments that are different from the one in which they live

(Development Matters, 2021, DfE)

More widely, children are thinking beyond their everyday lived experience and connecting their lives to others globally. Our work is based on high aspirations and a passionate belief in the limitless capacity of young children. Drawing on the synthesis of emotion and cognition ensures learning is lifelong. The critical development of their relational understanding of self to the natural world has seen children’s mental health improve and enabled them to see themselves as powerful contributors, with collective responsibilities, for the world in which they live and grow.

Read more:

Plus:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

early years foundation stage

pedagogy

resilience

wellbeing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Jonathan Doherty,

13 March 2023

Updated: 07 March 2023

|

NACE Associate Dr Jonathan Doherty outlines the focus of this year’s NACE R&D Hub on “oracy for high achievement” – exploring the impetus for this, challenges for schools, and approaches being trialled.

This year one of the NACE Research & Development Hubs is examining the theme of ‘oracy for high achievement’. The Hub is exploring the importance of rich and extended talk and cognitive discourse in the context of shared classroom practice. School leaders and teachers participating in the Hub are seeking to improve the value and effectiveness of speaking and listening. They are developing a body of knowledge about provision and pedagogy for more able learners, sharing ideas and practice and contributing to wider research evidence on oracy through their classroom-based enquiries.

Why focus on oracy?

Oracy is one of the most used and most important skills in schools. To be able to speak eloquently and with confidence, to articulate thinking and express an opinion are all essential for success both at school and beyond. Communication is a vital skill for the 21st century from the early years, through formal education, to employment. It embraces skills for relationship building, resolving conflict, thinking and learning, and social interaction. Oral language is the medium through which children communicate formally and informally in classroom contexts and the cornerstone of thinking and learning. The NACE publication Making Space for Able Learners found that “central to most classroom practice is the quality of communication and the use of talk and language to develop thinking, knowledge and understanding” (NACE, 2020, p.38).

Oracy is very much at the heart of classroom practice: modern classroom environments resound to the sound of students talking: as a whole class, in group discussions and in partner conversations. Teachers explaining, demonstrating, instructing and coaching all involve the skills of oracy. Planned purposeful classroom talk supports learning in and across all subject areas, encouraging students to:

- Analyse and solve problems

- Receive, act and build upon answers

- Think critically

- Speculate and imagine

- Explore and evaluate ideas

Dialogic teaching’ is highly influential in oracy-rich classrooms (Alexander, 2004). It uses the power of classroom talk to challenge and stretch students. Through dialogue, teachers can gauge students’ perspectives, engage with their ideas and help them overcome misunderstandings. Exploratory talk is a powerful context for classroom talk, providing students with opportunities to share opinions and engage with peers (Mercer & Dawes, 2008). It is not just conversational talk, but talk for learning. Given the importance and prevalence of classroom talk, it would be easy to assume that oracy receives high status in the curriculum, but its promotion is not without obstacles to overcome.

Challenges for schools in developing oracy skills

Covid-19 has impacted upon students’ oracy. A report from the children’s communication charity I CAN estimated that more than 1.5 million UK young people risk being left behind in their language development as a result of lost learning in the Covid-19 period (read more here). The Charity reported that the majority of teachers were worried about young people being able to catch up with their speaking and understanding as a result of the pandemic (I CAN, 2021).

With origins going back to the 1960s, the term oracy was introduced as a response to the high priority placed on literacy in the curriculum of the time. Rien ne change, with the current emphasis remaining exactly so. Literacy skills, i.e. reading and writing, continue to dominate the curriculum. Oracy extends vocabulary and directly helps with learning to read. The educationalist James Nimmo Britton famously said that “good literacy floats on a sea of talk” and recognised that oracy is the foundation for literacy.

Teachers do place value on oracy. In a 2016 survey by Millard and Menzies of 900 teachers across the sector, over 50% said they model the sorts of spoken language they expect of their students, they do set expectations high, and they initiate pair or group activities in many lessons. They also highlighted the social and emotional benefits of oracy and suggested it has untapped potential to support pupils’ employability – but reported that provision is often patchy and that CPD was sparse or even non-existent.

Another challenge is that oracy is mentioned infrequently in inspection reports. An analysis of reports of over 3,000 schools on the Ofsted database, undertaken by the Centre for Education and Youth in 2021, found that when taken in the context of all school inspections taking place each year, oracy featured in only 8% of reports.

The issue of how oracy is assessed is a further challenge. Assessment profoundly influences student learning. Changes to assessment requirements now provide schools with new freedoms to ensure their assessment systems support pupils to achieve challenging outcomes. Despite useful frameworks to assess oracy such as the toolkit from the organisation Voice 21, there is no accepted system for the assessment of oracy.

What are NACE R&D Hub participants doing to develop oracy in their schools?

The challenges outlined above make the work of participants in the Hub of real importance. With a focus on ‘oracy for high achievement’, the Hub is supporting teachers and leaders to delve deeper into oracy practices in their classrooms. The Hub supports small-scale projects through which they can evidence the impact of change and evaluate their practice. Activities are trialled over a short period of time so that their true impact can be observed in school and even replicated in other schools.

The participants are now engaged in a variety of enquiry-based projects in their classrooms and schools. These include:

- Use of the Harkness Discussion method to enable more able students to exhibit greater depth of understanding, complexity of response and analytical skills within cognitively challenging learning;

- Explicit teaching of oracy skills to improve independent discussion in science and history lessons;

- Introduction of hot-seating to improve students’ ability to ask valuable questions;

- Choice in oral tasks to improve the quality of students’ analytical skills;

- Oracy structures in collaborative learning to challenge more able students’ deeper learning and analysis;

- Better reasoning using oracy skills in small group discussion activities;

- Interventions in drama to improve the quality of classroom discussion.

Share your experience

We are seeking NACE member schools to share their experiences of effective oracy practices, including new initiatives and well-established practices. You may feel that some of the examples above are similar to practices in your own school, or you may have well-developed models of oracy teaching and learning that would be of interest to others. To share your experience, simply contact us, considering the following questions:

- How can we implement effective oracy strategies without dramatically increasing teacher workload?

- How can we best develop oracy for the most able in mixed ability classrooms?

- What approaches are most effective in promoting oracy in group work so that it is productive and benefits all learners?

- How can we implicitly teach pupils to justify and expand their ideas and make clear opportunities to develop their understanding through talk and deepen their understanding?

- How do we evidence challenge for oracy within lessons?

Teachers should develop students’ spoken language, reading, writing and vocabulary as integral aspects of the teaching of every subject. Every teacher is a teacher of oracy. The report of the All-Party Parliamentary Group inquiry into oracy in schools concluded that there was an indisputable case for oracy as an integral aspect of education. This adds to a growing and now considerable body of evidence to celebrate the place that oracy has in our schools and in our society. Oracy is in a unique place to support the learning and development of more able pupils in schools and the time to give oracy its due is now.

References

- Alexander, R. J. (2004) Towards dialogic teaching: Rethinking classroom talk. York, UK: Dialogos.

- Britton, J. (1970) Language and learning. London: Allen Lane. [2nd ed., 1992, Portsmouth NH: Boynton/Cook, Heinemann].

- I CAN (2021) Speaking Up for the Covid Generation. London: I CAN Charity.

- Lowe, H. & McCarthy, A. (2020) Making Space for Able Learners. Didcot, Oxford: NACE.

- Mercer, N. &. Dawes., L. (2008) The Value of Exploratory Talk. In Exploring Talk in School, edited by N. Mercer and S. Hodgkinson, pp. 55–71. London: Sage.

- Millard, W. & Menzies, L. (2016) The State of Speaking in Our Schools. London: Voice 21/LKMco.

- Millard, W., Menzies, L. & Stewart, G. (2021) Oracy after the pandemic: what Ofsted, teachers and young people think about oracy. Centre for Education & Youth/University of Oxford.

Read more:

Tags:

cognitive challenge

collaboration

confidence

CPD

critical thinking

language

metacognition

oracy

pedagogy

policy

questioning

research

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Amanda Hubball,

20 February 2023

Updated: 20 February 2023

|

NACE Associate Amanda Hubball, Deputy Head and More Able Lead at Challenge Award-accredited Alfreton Nursery School, shares five key approaches to embed metacognition in the early years.

At Alfreton Nursery School metacognition has been systematically embedded across the whole curriculum for the last three years. Through the use of an approach constructed by Roger Sutcliffe (DialogueWorks) called Thinking Moves, we’ve successfully implemented an innovative approach to learning.

When we talk about the progression of mathematical understanding we have a shared language. We all understand what it means to engage in addition and subtraction. Phonics, science . . . all areas of learning have a common linguistic foundation.

However, when it comes to the skills of thinking and learning, there is no common language and the concepts are shrouded in misconception. Do children learn visually, kinaesthetically . . . ? Are there different levels to learning? Based on the belief that we are all thinking and learning all of the time, Thinking Moves has been implemented at Alfreton Nursery School. Thinking Moves provides the language to explain the process of thinking and has thus provided a common framework on which to master learning.

1. Develop and model a shared vocabulary

A shared vocabulary, used by all staff and children, has provided the adults with a tool to explain teaching, and the children with a tool to aid learning. Crucially, the commonality in language means that learning is transparent. For example, when children explain what comes next in a story, they are using the A in the A-Z: thinking Ahead. During the story recall children are using B: thinking Back. The A-Z of Thinking Moves supports children to consciously choose and communicate the thinking strategies they intend to use, are using, or have used to achieve success.

Teaching staff build on the more commonly used Thinking Moves words, whilst subtly introducing less familiar terms. The use of synonyms within conversation, to accompany the language of Thinking Moves, supports both adults and children to use the words in context.

“I’m going to think ahead, cos I need to choose the bricks I need to build my rocket.”

2. Embed metacognitive concepts in the learning environment

The learning environment critically supports the children’s use of metacognition. With each word comes a symbol. These symbols are used to visually illustrate Thinking Moves. Children use these symbols to explain what type of thinking they are engaged in and what they need to do next.

The integration of the symbols into the classroom environment has ensured that there is conscious intent to implement metacognition within all areas of the curriculum. Teachers use the symbols as prompts. Children use the symbols to help them articulate their thinking and as an aid to knowing what strategies will help them further.

Through immersing children in the visual world of metacognition, all children – regardless of age and stage of development – are supported in their learning.

3. Break it down into manageable chunks

The A-Z includes some words which slide easily into conversation. Other words are less easily integrated into everyday speech. In order to ensure that a variation of language is incorporated throughout the curriculum, specific areas of the curriculum have dedicated Thinking Moves words. For example, Expressive Art and Design have embraced the metacognitive moves of Vary, Zoom and Picture. This ‘step by step’ strategy gives teaching staff the confidence to learn and use the A-Z in small chunks.

Over time, as confidence grows, the use of metacognitive language becomes a natural part of daily discourse. Whether in the staffroom over lunch, planning the timetable or sharing a jigsaw, metacognition has become a part of daily life.

4. Use to support targeted teaching across the curriculum

Metacognition is embedded throughout continuous provision and is accessed by all children through personalised interactions. Enhancements are offered across the curriculum and metacognition forms a vehicle on which targeted teaching is delivered. For example, by combining thinking moves together, we have created thinking grooves. By using certain moves together, the flow of thinking is explicit.

Within our maths enhancements we use the maths QUEST approach. A session begins with a Question, e.g. “How many will we have if we add one more to this group?” Children Use their mathematical understanding and Explain what they will need to do to solve the problem. The answer is Sized, “Are there more or less now?”, and then this is Tested to establish the consistency of the answer. Maths QUESTs now underpin our mathematical enhancements, allowing children to consciously use maths and metacognition simultaneously.

5. Embed within progression planning

When looking at the curriculum and skill progression across the school, it has been helpful to consider which Thinking Moves explicitly support advancement. For children to progress in their acquisition of new concepts, they need to know clearly how to access their learning. Within our planning and assessment systems, areas of metacognitive focus have been identified.

For example, within literacy we have raised our focus on the Thinking Move Infer. For children to gather information from a story is a key skill for future progression. Within science we emphasise the need to Test and within music we support children to Respond. Progression planning now has a clear focus on cognitive challenge, as well as subject knowledge.

Embedding metacognition in the early years supports children to master their own cognition and gives them a voice for life.

Further reading:

Plus:

Tags:

critical thinking

early years foundation stage

metacognition

pedagogy

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Howell's School, Llandaff,

20 June 2022

|

Sue Jenkins, Head of Years 10 and 11, and Hannah Wilcox, Deputy Head of Years 10 and 11, share five reasons they’ve found The Day an invaluable resource for tutor time activities.

Howell’s School, Llandaff, is an independent school in Cardiff which educates girls aged 3-18 and boys aged 16-18. It is part of the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST).

The Day publishes daily news articles and resources with the aim of help teachers inspire students to become critical thinkers and better citizens by engaging their natural curiosity in real-world problems. We first came across it as a library resource and recognised its potential for pastoral activities when the length of our tutor time sessions was extended to allow more discussion time and flexibility in their use.

Post-Covid, it has never been more important to promote peer collaboration, discussion and debate in schools. There is an ever-increasing need for students to select, question and apply their knowledge when researching; it has never been more important for students to have well-developed thinking and analytical skills. We find The Day invaluable in helping us to prompt students to discuss and understand current affairs, and to enable those who are already aware to extend and debate their understanding.

Here are five key pastoral reasons why we would recommend subscribing to The Day:

1. Timely, relevant topics throughout the year

You will always find a timely discussion topic on The Day website. The most recent topics feature prominently on the homepage, and a Weekly Features section allows you to narrow down the most relevant discussion topic for the session you are planning. Assembly themes, such as Ocean Day in June, are mapped across the academic year for ease of forward planning. We particularly enjoyed discussing the breakaway success of Emma Raducanu in the context of risk-taking, and have researched new developments in science, such as NASA’s James Webb telescope, in the week they have been launched.

2. Supporting resources to engage and challenge students

The need to involve and interest students, make sessions straightforward for busy form tutors, and cover tricky topics, combine to make it daunting to plan tutor time sessions – but resources linked to The Day’s articles make it manageable. Regular features such as The Daily Poster allow teachers to appeal to all abilities and learning styles with accessible and interesting infographics. These can also be printed and downloaded for displays, making life much easier for academic departments too. One of the best features we’ve found for languages is the ability to read and translate articles in target languages such as French and Spanish. Reading levels can be set on the website for literacy differentiation, and key words are defined for students to aid their understanding of each article.

3. Quick PSHE links for busy teachers

Asked to cover a class at the last minute? We’ve all been there! With The Day, you are sure to find a relevant subject story to discuss within seconds, and, best of all, be certain that the resources are appropriate for your students. With our Year 10 and 11 students, we have covered topics such as body image with the help of The Day by prompting discussion of Kate Winslet’s rejection of screen airbrushing. Using articles is particularly useful with potentially difficult or emotive issues where students may be more able to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of certain attitudes by looking at news events, detaching themselves from but also gaining insight about the personal situations they may be experiencing. The PSHE programme is vast; it is great to use The Day to plan tutor time sessions and gives us the opportunity to touch on a wide range of issues relatively easily.

4. Motivational themes brought to life through real stories

We have also found The Day’s articles useful for providing examples of motivational themes for our year groups. The Themes Calendar is particularly useful here; for example, tutor groups discussed the themes of resilience and diversity using the article on Preet Chandi’s trek to the South Pole. If you’re looking for assembly inspiration, The Day is a great starting point.

5. Develop oracy, thinking and research skills through meaningful debate

Each article has suggested tasks and discussion questions which we have found very useful for planning tutor time activities which develop students’ oracy, thinking and research skills. The Day promotes high-level debates about environmental, societal and political issues which students are keen to explore. One recent example is the discussion of privacy laws and press freedom prompted by the article about Rebel Wilson’s forced outing by an Australian newspaper. Activities can be easily adapted or combined to promote effective discussion. ‘Connections’ articles contain links to similar areas of study, helping teachers to plan and students to see the relevance of current affairs.

Find out more…

NACE is partnering with The Day on a free live webinar on Thursday 30 June, providing an opportunity to explore this resource, and its role within cognitively challenging learning, in more detail. You can sign up here, or catch up with the recording afterwards in our webinars library (member login required).

Plus: NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to The Day. For details of this and all current member offers, take a look at our member offers page (login required).

Tags:

critical thinking

enrichment

independent learning

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

libraries

motivation

oracy

personal development

questioning

research

resilience

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ilona Bushell,

28 March 2022

Updated: 22 March 2022

|

Ilona Bushell, Assistant Editor at The Day

Telling the truth about the world we share has become one of the heroic endeavours of the age amidst an ever-changing digital tsunami of information. Effectively embedding journalism in your school is vital to equip young citizens with the skills needed to develop a healthy worldview, engage in a democratic society and tackle the world’s biggest challenges, leading the way to a brighter future.

There is no doubt that news literacy helps develop skills that are valuable right across the curriculum – and prepares children for their adult life. As these young people become voters, tax-payers and earners, they will have the basic tools to navigate the noise, confusion and fog of reality.

Here at the online newspaper for schools, The Day, we call the regular consumption of news a “real-world curriculum”. In February 2022 we launched The Global Young Journalist Awards (GYJA), a free competition open to all under 18s around the world. We aim to inspire young people to build a better world through storytelling, and the ambition is for GYJA to become the leading award for youth journalism. What, why, and why now?

Written entries are welcome, but the awards are open to work in any medium – including video, photo, audio, graphic or podcast – opening up the floor to different student abilities and areas of interest. The aim is to showcase a variety of voices and encourage young people to report on what truly matters to them.

American actor and comedian Tina Fey, who will be among the panel of GYJA judges, said, “There has never been a more important time to get young people involved in truth-seeking. It is vital for our future that journalists investigate without fear or favour, and this competition is an excellent way of inspiring children to get involved.”

The judging panel also includes TV broadcaster Ayo Akinwolere, the BBC’s gender and identity correspondent Megha Mohan, the FT’s top data journalism developer Ændra Rininsland, and Guardian columnist Afua Hirsch.

Indian computer scientist and educational theorist Sugata Mitra sees the awards as an opportunity to see glimpses of unexplored minds: “I have found children to be good at making up things. They can assemble all sorts of information into stories that are, at worst, fascinating and, at best, brutally honest. A journalist that can think like a nine-year-old will be astonishing… Can nine-year-olds think like a journalist?”

How are the awards aligned to school curricula?

There is an explosion of great reporting today on topics relevant to every area of the school curriculum. The award categories listed below are designed to fit within students’ areas of study and contribute to a rich real-world curriculum. Through their storytelling, entrants can build on important skills including communication, research, fact-checking, confidence, literacy, oracy, individuality and empathy.

GYJA categories:

1. Campaigning journalist of the year

2. Interviewer of the year

3. International journalist of the year

4. Political journalist of the year

5. Mental health journalist of the year

6. Environment journalist of the year

7. Science & technology journalist of the year

8. Race & gender journalist of the year

9. Sports journalist of the year

10. Climate journalist of the year (primary only)

How can schools get involved?

Teachers can download the Awards entry pack at www.theday.co.uk/gyja2022. The entry pack and website include a host of free resources for students. There are top tips from sponsors and judges, prompt ideas, best practice examples and guidance on the six journalistic formats they can use. What’s in store for the winners?

Winners will be announced at a live virtual ceremony in June. Award winners will have their words, video, photo, graphic or podcast published on The Day’s website and be given the chance to connect with role models from the world of media and current affairs.

Winners will be invited to join The Day’s Student Advisory Board for a year, while winners and runners-up will be offered a day’s work experience in a national newsroom and receive trophies.

Competition sponsors include The Fairtrade Foundation, The Edge Foundation, Oddizzi, Brainwaves, National Literacy Trust and Hello World.

About The Day

The Day is a digital newspaper for use in schools and colleges. It has a daily average circulation of 378,000 students, the largest readership among those aged 18 and under of any news title. Over 1,300 schools are subscribers. NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on subscriptions to The Day; for details of this and all NACE member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

Tags:

competitions

critical thinking

English

enquiry

free resources

independent learning

literacy

research

student voice

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|