Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Helen Morgan,

01 December 2025

Updated: 01 December 2025

|

Helen Morgan, Subject Leader for Reading, English Lead Practitioner, More Able Champion & DDSL at St Michael Catholic Primary School & Nursery in Ashford, Surrey

With the ‘Year of Reading’ fast approaching, it’s a good time to re-assess the provisions in place for our children. As an English lead, questions I ask myself often revolve around the following…

- What are our children reading?

- Why do they make the choices that they do?

- In what ways can I support them?

This is especially important when it comes to children sharing what they have read, as I believe there are many effective ways to do this other than merely completing a reading record book. After I have read a great book (or a terrible one for that matter) there’s nothing I love more than discussing it with others. It was for this reason that I joined a ‘Teachers’ Reading Group’, facilitated by The Open University’s Reading for Pleasure volunteers.

The project I undertook at the end of the year involved setting up a staff book club where we read and discussed children’s books. It was very successful, in more ways than I realised it would be:

- We really enjoyed reading and discussing the texts.

- It broadened our knowledge of children’s literature.

- As staff finished reading the books, they were placed in class libraries.

- We noticed that groups of children were taking the books and reading them together, forming their own small book groups.

As the NACE lead at my school, I considered how I could use my findings to benefit more groups of children, so I started running a book club for our more able children. I adopted the Reading Gladiators programme curated by Nikki Gamble and the team at Just Imagine, which focuses on high-level discussion and eliciting creative responses to quality texts. Over the years these book clubs have been extremely popular, so we now run additional book clubs for less engaged readers and a picture book club with a focus on visual literacy.

Here are five reasons why I believe book clubs are a valuable way to foster reading for pleasure for all children, through informal, dialogic group discussion.

1) They develop critical and reflective thinking.

- Through guided discussion, children learn to justify opinions with evidence and challenge assumptions elicited from both the text and from each other.

- The discussions foster metacognition and allow children to deepen their thinking. Research has shown that this links to higher achievement.

2) They nurture social and emotional intelligence.

- Children build their skills in empathy through exploring different perspectives, including that of their peers.

- It allows children time to reflect on and enjoy what they are reading without the pressure of having to answer formal questions.

3) They foster independence and help children to make meaningful connections.

- Book clubs expose children to a wide range of texts that they might not choose independently.

- They enable leaders to read with rather than to children.

- Reading for pleasure thrives when children can relate what they read to themselves, other texts and the world, thus deepening their ideas.

4) They encourage dialogic interaction.

- Book clubs encourage children to verbalise their interpretations and listen to others’ viewpoints.

- Discussion helps them move from literal understanding to analysis and evaluation — exploring themes, author choices, and symbolism.

- Informal book talk enables children to build empathy whilst exploring different perspectives.

- Collaborative reading builds confidence, listening skills, and the ability to challenge each other’s thinking, which are key aspects of social learning.

5) They promote agency, create a community of readers and foster a love of reading.

- When children play an integral part in discussion direction, they feel ownership and autonomy.

- Book clubs shift reading from a solitary task to a social practice.

- This helps to build a community of engaged readers who are invested, curious and motivated.

References

Tags:

critical thinking

independent learning

reading

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Trellech Primary School,

17 April 2023

Updated: 17 April 2023

|

Kate Peacock, Acting Headteacher at Trellech Primary School, explains how “SMILE books” have been introduced to develop pupil voice and independent learning, while also improving staff planning.

Our vision, here at Trellech Primary, is to ensure the four purposes of the Curriculum for Wales are at the heart of our children’s learning – particularly ensuring that they are “ambitious capable learners” who:

- Set themselves high standards and seek and enjoy challenge;

- Are building up a body of knowledge and have the skills to connect and apply that knowledge in different contexts;

- Are questioning and enjoy solving problems.

What is a “SMILE Curriculum”?

We have always been very proud of the children at Trellech Primary, where we see year on year pupils making good progress in all areas of the curriculum. Following the publication of Successful Futures and curriculum reform in Wales, the school wanted to embrace the changes and be forward-thinking in recognising and nurturing children as learners who are responsible for planning and developing their own learning. As a Pioneer School, we made a commitment to:

- Give high priority to pupil voice in developing their own learning journey.

- Develop pupil voice throughout each year group, key stage and the whole school.

- Embrace the curriculum reform and develop children’s understanding.

- Allow all learners to excel and reach their full potential.

- Ensure each child is given the opportunity to make good progress.

These goals have been developed alongside the introduction of SMILE books, based on our SMILE five-a-day culture:

- Standards

- Modelled behaviour

- Inspiration

- Listening

- Ethical

What is a “SMILE book”?

Based on these key values of the SMILE curriculum, the SMILE books are A3-sized, blank-paged workbooks which learners can use to present their work however they choose. They are used to present the children’s personal learning journey. In contrast to the use of books for subject areas, SMILE books show the development of skills from across the Areas of Learning and Experience (AoLEs) in their own preferred style.

This format enables pupil voice to be at the fore of their journey, while clearly promoting each pupil’s independent learning and supporting individual learning styles. Within a class, each SMILE book will look different, despite the same themes being part of the teaching and learning. Some may be presented purely through illustration with relevant vocabulary, while others develop and present their learning through greater use of text.

Launching the SMILE books

As a Pioneer School we collaborated with colleagues who were at the same point of their curriculum journey as us. Following this collaboration, we agreed to trial the introduction of our SMILE books in Y2 and Y6 with staff who were members of SLT and involved in curriculum reform.

In these early stages, expectations were shared and pupils were given a variety of resources to enable them to present their work in their preferred format within the books – enabling all individuals to lead, manage and present their knowledge, skills and learning independently.

Pupil and parent feedback at Parent Sharing Sessions highlighted positive feedback and demonstrated pupils’ pride in the books. Consequently, SMILE books were introduced throughout the school at the start of the following academic year. For reception pupils scaffolding is provided, but as pupils move through the progression steps less scaffolding is needed; pupil independence increases and is clearly evident in the way work across the AoLEs is presented.

Staff SMILE planning

Following the success of the implementation of pupil SMILE books and to ensure clarity in understanding of the Curriculum for Wales, I decided to trial the SMILE book format myself, to record my planning. This helped me to develop greater depth of knowledge and understanding of the Four Purposes, Cross-Curricular Links, Pedagogical Principles and the What Matters Statements for each of the AoLEs.

During this early trial I wrote each of the planning pages by hand, which enabled me to internalise the curriculum with an increased understanding. Also included were the ideas page for each theme and pupil contributions through the pupil voice page.

This format was shared with the whole staff and has evolved over time. Some staff continue to write and present planning in a creative form, while others use QR codes to link planners to electronic planning sheets and class tracking documentation. The inclusion of the I Can Statements has enabled staff to delve deeper and focus on less but better.

Each SMILE medium-term planning book moves with the cohort of learners, exemplifying their learning journey through the school. The investment of time in medium-term planning enables staff to focus on skills development in short-term planning time. This is evident in the classroom, where lessons focus on skills development and teachers are seen as facilitators of learning.

Impact on teaching and learning

Following our NACE Challenge Award reaccreditation in July 2021, it was recognised that the use of SMILE books had a positive impact on pupil voice and the promotion of independent learning for all. Our assessor reported:

SMILE books, which the school considers to be at the heart of all learning, are used by all year groups. Children complete activities independently in their books showing their own way of learning and presenting their work in a range of styles and formats. As a result, even from the youngest of ages, pupils have become more independent learners who are engaged in their learning because they have been involved in the decision-making process for the topics being taught.

The SMILE approach to learning has strengthened pupil voice and given children the confidence to take risks in their own learning by choosing how they like to learn.

The SMILE approach to learning has created a climate of trust where learners are confident to take risks without the fear of failure and are valued for their efforts. Pupils appreciate that valuable learning often results from making mistakes.

SMILE promotes problem solving and enquiry-based activities to help nurture independent learning.

Using SMILE books, independent learning is promoted and encouraged from the youngest of ages. The SMILE approach encourages MAT learners to lead their own learning by equipping them with the skills and knowledge to know how they best learn. As a result, more able pupils are critical thinkers and have high expectations and aspirations for themselves.

Our SMILE approach continues to develop here at Trellech, ensuring the continual development of our learners and independent learners with a valued voice.

Explore NACE’s key resources for schools in Wales

Tags:

Challenge Award

creativity

curriculum

independent learning

professional development

student voice

Wales

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By The Mulberry House School,

06 July 2022

|

Naomi Parkhill is Deputy Headteacher for Pastoral Care at The Mulberry House School, which recently attained the NACE Challenge Award for the third time. In this blog post, she shares some of the ways in which the school ensures challenge is embedded throughout all aspects of the school’s provision, for all learners.

At The Mulberry House School we are firm believers that challenge is not something that should be saved solely for the most able pupils, but should be readily available for all. With our school ethos being “We reach high to be the people we want to be, respect ourselves and others and enjoy each new challenge”, it is of utmost importance to us that challenge permeates the very centre of who we are as a school. We have a broad curriculum and value each subject equally. All of our children are encouraged to find their own strength and adopt a growth mindset across both curricular and extracurricular activities.

Here are our top five tips for putting challenge at the heart of your school.

1. Know what excellence looks like

To challenge pupils to produce the very best work they are capable of, the teacher needs to ensure that they have got a firm understanding of what this looks like, both for the subject/area they are delivering and for the age of the children. This needs to incorporate both knowledge and skills. We have spent a lot of time as a school collaboratively deciding on the standards that we are aiming for; it is important that all staff agree on this in order to provide consistent challenge for all pupils.

2. Share this vision explicitly with learners

Once a decision has been made about what excellence looks like, it is important that we share this with our pupils. It is important to note that this is not limited to sharing examples of excellent work; the children need to know what it is that makes that piece of work excellent. This can be achieved through effective modelling, in which the teacher explains the thought process of an ‘expert’ in the subject as they work, helping to raise the standards of work for all. Another way to empower the children to strive for excellence is through carefully constructed success criteria, which act as a set of instructions to achieve the learning objective, again supporting challenge for all.

3. Empower learners to embrace new challenges

As a growth mindset school we wholeheartedly believe that anyone can improve if they try. A central part of our Mulberry House Way is “Try your best to be your best”. Through instilling this learning attitude in our children from a young age, they are prepared to accept challenges and give everything their maximum effort. Scaffolding plays a key role in supporting our children to achieve excellence. This allows us to provide each child or class with what they need to ensure that they produce the highest quality of work that they can. Allow the children to practise getting things right, then over time remove this support; this will lead to them creating a high standard of work independently.

4. Provide challenging extension and enrichment opportunities

Our recent case study exploring “Enrichment vs Extension” as a means of providing challenge for all – submitted as part of our recent NACE Challenge Award reaccreditation – has been successful in supporting the “challenge for all” aims of the NACE Challenge Development Programme. The outcomes of this case study have enriched the quality-first teaching that we endeavour to deliver. This has, in turn, impacted favourably on our children’s outcomes. We have spent time researching the difference between extension and enrichment opportunities and gaining an understanding of the value of each. We plan and deliver lessons that are centred on enrichment opportunities, with extension activities supporting individual learners to either close gaps or take the next step in their learning.

5. Encourage children to share their opinions

Central to the development of each child across the curriculum is their confidence to share their opinions and thought processes. From an early age we believe it is important to enable our children to explain how they have reached an answer and so the focus is on this rather than simply just providing the “correct” answer. In essence, we have started to embed metacognition, thinking about one’s thinking, in our Key Stage 1 learning. The impact that this has had on both children’s attitudes towards learning and academic outcomes has been significant. We look forward to rolling this out through our EYFS classes and seeing the impact this has.

How does your school provide challenge for all? Contact us to share your experience.

Tags:

confidence

early years foundation stage

enrichment

independent learning

KS1

leadership

metacognition

mindset

pedagogy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Howell's School, Llandaff,

20 June 2022

|

Sue Jenkins, Head of Years 10 and 11, and Hannah Wilcox, Deputy Head of Years 10 and 11, share five reasons they’ve found The Day an invaluable resource for tutor time activities.

Howell’s School, Llandaff, is an independent school in Cardiff which educates girls aged 3-18 and boys aged 16-18. It is part of the Girls’ Day School Trust (GDST).

The Day publishes daily news articles and resources with the aim of help teachers inspire students to become critical thinkers and better citizens by engaging their natural curiosity in real-world problems. We first came across it as a library resource and recognised its potential for pastoral activities when the length of our tutor time sessions was extended to allow more discussion time and flexibility in their use.

Post-Covid, it has never been more important to promote peer collaboration, discussion and debate in schools. There is an ever-increasing need for students to select, question and apply their knowledge when researching; it has never been more important for students to have well-developed thinking and analytical skills. We find The Day invaluable in helping us to prompt students to discuss and understand current affairs, and to enable those who are already aware to extend and debate their understanding.

Here are five key pastoral reasons why we would recommend subscribing to The Day:

1. Timely, relevant topics throughout the year

You will always find a timely discussion topic on The Day website. The most recent topics feature prominently on the homepage, and a Weekly Features section allows you to narrow down the most relevant discussion topic for the session you are planning. Assembly themes, such as Ocean Day in June, are mapped across the academic year for ease of forward planning. We particularly enjoyed discussing the breakaway success of Emma Raducanu in the context of risk-taking, and have researched new developments in science, such as NASA’s James Webb telescope, in the week they have been launched.

2. Supporting resources to engage and challenge students

The need to involve and interest students, make sessions straightforward for busy form tutors, and cover tricky topics, combine to make it daunting to plan tutor time sessions – but resources linked to The Day’s articles make it manageable. Regular features such as The Daily Poster allow teachers to appeal to all abilities and learning styles with accessible and interesting infographics. These can also be printed and downloaded for displays, making life much easier for academic departments too. One of the best features we’ve found for languages is the ability to read and translate articles in target languages such as French and Spanish. Reading levels can be set on the website for literacy differentiation, and key words are defined for students to aid their understanding of each article.

3. Quick PSHE links for busy teachers

Asked to cover a class at the last minute? We’ve all been there! With The Day, you are sure to find a relevant subject story to discuss within seconds, and, best of all, be certain that the resources are appropriate for your students. With our Year 10 and 11 students, we have covered topics such as body image with the help of The Day by prompting discussion of Kate Winslet’s rejection of screen airbrushing. Using articles is particularly useful with potentially difficult or emotive issues where students may be more able to discuss the benefits and drawbacks of certain attitudes by looking at news events, detaching themselves from but also gaining insight about the personal situations they may be experiencing. The PSHE programme is vast; it is great to use The Day to plan tutor time sessions and gives us the opportunity to touch on a wide range of issues relatively easily.

4. Motivational themes brought to life through real stories

We have also found The Day’s articles useful for providing examples of motivational themes for our year groups. The Themes Calendar is particularly useful here; for example, tutor groups discussed the themes of resilience and diversity using the article on Preet Chandi’s trek to the South Pole. If you’re looking for assembly inspiration, The Day is a great starting point.

5. Develop oracy, thinking and research skills through meaningful debate

Each article has suggested tasks and discussion questions which we have found very useful for planning tutor time activities which develop students’ oracy, thinking and research skills. The Day promotes high-level debates about environmental, societal and political issues which students are keen to explore. One recent example is the discussion of privacy laws and press freedom prompted by the article about Rebel Wilson’s forced outing by an Australian newspaper. Activities can be easily adapted or combined to promote effective discussion. ‘Connections’ articles contain links to similar areas of study, helping teachers to plan and students to see the relevance of current affairs.

Find out more…

NACE is partnering with The Day on a free live webinar on Thursday 30 June, providing an opportunity to explore this resource, and its role within cognitively challenging learning, in more detail. You can sign up here, or catch up with the recording afterwards in our webinars library (member login required).

Plus: NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on annual subscriptions to The Day. For details of this and all current member offers, take a look at our member offers page (login required).

Tags:

critical thinking

enrichment

independent learning

KS3

KS4

KS5

language

libraries

motivation

oracy

personal development

questioning

research

resilience

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ilona Bushell,

28 March 2022

Updated: 22 March 2022

|

Ilona Bushell, Assistant Editor at The Day

Telling the truth about the world we share has become one of the heroic endeavours of the age amidst an ever-changing digital tsunami of information. Effectively embedding journalism in your school is vital to equip young citizens with the skills needed to develop a healthy worldview, engage in a democratic society and tackle the world’s biggest challenges, leading the way to a brighter future.

There is no doubt that news literacy helps develop skills that are valuable right across the curriculum – and prepares children for their adult life. As these young people become voters, tax-payers and earners, they will have the basic tools to navigate the noise, confusion and fog of reality.

Here at the online newspaper for schools, The Day, we call the regular consumption of news a “real-world curriculum”. In February 2022 we launched The Global Young Journalist Awards (GYJA), a free competition open to all under 18s around the world. We aim to inspire young people to build a better world through storytelling, and the ambition is for GYJA to become the leading award for youth journalism. What, why, and why now?

Written entries are welcome, but the awards are open to work in any medium – including video, photo, audio, graphic or podcast – opening up the floor to different student abilities and areas of interest. The aim is to showcase a variety of voices and encourage young people to report on what truly matters to them.

American actor and comedian Tina Fey, who will be among the panel of GYJA judges, said, “There has never been a more important time to get young people involved in truth-seeking. It is vital for our future that journalists investigate without fear or favour, and this competition is an excellent way of inspiring children to get involved.”

The judging panel also includes TV broadcaster Ayo Akinwolere, the BBC’s gender and identity correspondent Megha Mohan, the FT’s top data journalism developer Ændra Rininsland, and Guardian columnist Afua Hirsch.

Indian computer scientist and educational theorist Sugata Mitra sees the awards as an opportunity to see glimpses of unexplored minds: “I have found children to be good at making up things. They can assemble all sorts of information into stories that are, at worst, fascinating and, at best, brutally honest. A journalist that can think like a nine-year-old will be astonishing… Can nine-year-olds think like a journalist?”

How are the awards aligned to school curricula?

There is an explosion of great reporting today on topics relevant to every area of the school curriculum. The award categories listed below are designed to fit within students’ areas of study and contribute to a rich real-world curriculum. Through their storytelling, entrants can build on important skills including communication, research, fact-checking, confidence, literacy, oracy, individuality and empathy.

GYJA categories:

1. Campaigning journalist of the year

2. Interviewer of the year

3. International journalist of the year

4. Political journalist of the year

5. Mental health journalist of the year

6. Environment journalist of the year

7. Science & technology journalist of the year

8. Race & gender journalist of the year

9. Sports journalist of the year

10. Climate journalist of the year (primary only)

How can schools get involved?

Teachers can download the Awards entry pack at www.theday.co.uk/gyja2022. The entry pack and website include a host of free resources for students. There are top tips from sponsors and judges, prompt ideas, best practice examples and guidance on the six journalistic formats they can use. What’s in store for the winners?

Winners will be announced at a live virtual ceremony in June. Award winners will have their words, video, photo, graphic or podcast published on The Day’s website and be given the chance to connect with role models from the world of media and current affairs.

Winners will be invited to join The Day’s Student Advisory Board for a year, while winners and runners-up will be offered a day’s work experience in a national newsroom and receive trophies.

Competition sponsors include The Fairtrade Foundation, The Edge Foundation, Oddizzi, Brainwaves, National Literacy Trust and Hello World.

About The Day

The Day is a digital newspaper for use in schools and colleges. It has a daily average circulation of 378,000 students, the largest readership among those aged 18 and under of any news title. Over 1,300 schools are subscribers. NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on subscriptions to The Day; for details of this and all NACE member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

Tags:

competitions

critical thinking

English

enquiry

free resources

independent learning

literacy

research

student voice

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By School Library Association,

28 March 2022

Updated: 24 March 2022

|

Dawn Woods, Member Development Librarian, and Hannah Groves, Marketing and Communications Officer, School Library Association

If there is one subject a librarian can help teaching colleagues with, it is definitely history. From providing engaging reads for primary pupils to assisting with A-Level research for the curriculum or supporting EPQ projects, the school library is home to a wealth of resources.

For primary pupils, a history topic may start with a novel set during the period to be studied. Historical novels take the reader back to explore how life was during that time and can help explain the historical context. Library staff will be able to suggest a range of suitable titles to help with this, whatever the period.

GCSE-level students will be expected to read around the subject to complete their homework, and so the librarian will introduce pupils to the library catalogue to help them locate the resources available to them. As well as hardcopy books, e-books and online journals will be catalogued under subject headings, so students searching for their history topic are alerted to what the library holds on that subject, whatever the media format. By the time students are on their A-Level course, they will be using these to research curriculum topics and, in the case of the EPQ, on topics of their own choice.

Here are three key ways your school library can support the teaching of history:

1. Use the library catalogue as a research tool

School library staff will teach students that the library catalogue is a gateway to resources in many formats, all grouped under keyword headings, preparing our young people for independent learning. Once students go on to university they will require this very skill, so they will be well prepared for further study.

2. Share curated content and resources

Some libraries may present students with resources as a reading list, some may have Padlets or other online presentations. The value of these online presentations is that they take pupils directly to the sites librarians have already earmarked as useful for the topic. As Padlets contain all types of content – whether that be text, documents, images, videos or weblinks – librarians can bring together a wide range of material for a particular class or year group and subject. For example, this Padlet on ‘history for all ages’ contains reading lists as well as weblinks to safe sites for primary and secondary students. This means that young people are not wasting time finding unsuitable resources, which may lead them to the wrong conclusions.

3. Subscribe to online journals

If your school offers the EPQ, where older secondary students choose their own topic, students must research this themselves. The library is integral to this and subscriptions to online journals can help enormously here. The topic students are researching may be very specific and not generally covered in published books which, by the very nature of going through the publishing process, take a long time to be available. Research written up in journals is current and academically verified, so with a subscription to a resource such as JSTOR students have access to “peer-reviewed scholarly journals, respected literary journals, academic monographs, research reports, and primary sources from libraries’ special collections and archives.” [Another example is Hodder’s Review magazines, which NACE members recently trialled.]

The school library and library staff are your friends when teaching history to learners of any age, so do make sure you use their resources to save time for all.

About the School Library Association

The School Library Association (SLA) is a charity that works towards all schools in the UK having their own (or shared) staffed library. Our vision is for all school staff and children to have access to a wide and varied range of resources and have the support of an expert guide in reading, research, media and information literacy. To find out more about what the SLA could do for you, visit our website, follow us on Twitter, or get in touch.

Read more:

Tags:

enrichment

history

historyfree resources

independent learning

literacy

reading

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By NACE team,

10 February 2022

|

Hodder Education’s Review magazines provide subject-specific expertise aimed at GCSE and A-level students, featuring the latest research, thought-provoking articles, exam-style questions and discussion points to deepen learners’ subject knowledge and develop independent learning skills.

Earlier this academic year, we partnered with Hodder on a live webinar for NACE members, followed by an opportunity to undertake a free trial subscription to the Review magazines, and then reconvening for an online focus group to share experiences, ideas and feedback.

Below are 15 ways NACE members suggested this resource could be used:

- Wider reading – encouraging learners to read more widely in their subjects, developing deeper and broader subject knowledge

- Flipped learning – tasking students with reading an article (or articles) on a topic ahead of a lesson, so they are prepared to discuss during class time (members noted that this approach benefits from practising reading comprehension during lesson time first)

- Developing cultural capital – exposure to content, contexts, vocabulary, and text formats which learners might not otherwise encounter

- Independent research and project work – to support independent research and projects such as EPQs, for example by using the digital archives to search on a particular theme

- Developing literacy and vocabulary – exposure to subject-specific and advanced vocabulary; this was highlighted by some schools as a particular concern post-pandemic

- Shared text during lessons – used to support lessons on a particular topic, and/or to develop comprehension skills

- Developing exam skills – using the magazines’ links to specific exam skills/modules, and practice exam questions at the end of articles

- Examples of academic/exam skills in practice – providing examples of how a text or topic could be approached and analysed, and ways of structuring an essay/response

- Library resource – signposted to students and teachers by school librarian to ensure a diverse, challenging reading menu is available to all

- Linking learning to real-world contexts – providing examples of how curriculum content is being applied in current contexts around the world, helping to bring learning to life

- Broadening career horizons – examples of different careers in each subject area, giving learners exposure to a range of potential future pathways

- Extracurricular provision – used as a resource to support subject-specific clubs, or general research/debate clubs

- Developing critical thinking and oracy skills – to support strategies such as the Harkness method, as part of a wider focus on developing critical thinking and oracy skills

- Exposure to academic research – preparing students for further education and career opportunities

- Fresh perspectives on curriculum content – new angles and insights on well-established modules and topics – for teachers, as well as students!

Find out more:

Discount offer for NACE members

NACE members can benefit from a 25% discount on Hodder's digital and print resources, including the Review magazines (excluding student £15 subscriptions). To access this, and our full range of member offers, log in and visit our member offers page.

Does your school use the Review magazines or a similar resource? To share your experience and ideas, contact communications@nace.co.uk

Tags:

aspirations

enrichment

independent learning

KS4

KS5

literacy

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Kyriacos Papasavva,

26 August 2021

|

Kyriacos Papasavva, Head of Religious Studies at St Mary’s and St John’s (SMSJ) CE School, shares three ways in which the school seeks to nurture a love of learning – for students and staff alike.

Education becomes alive when educators and students love what they do. This is, I think, the whole point of teaching: to inspire a love of learning among those we teach. Love, however, is not something that can be forced. Instead, it is ‘caught’.

For such a desire to develop in our pupils, there must be a real freedom in the learning journey. From the teacher’s perspective, this can be a scary prospect, but we must remember that a teacher is a guide only; you cannot force children to learn, but it is genuinely possible to inspire among pupils a love of learning. To enable this, we should ask ourselves: to what extent do we as teaching practitioners allow the lesson to go beyond the bulwark we impose upon any limited, pre-judged ‘acceptable range’? How do we allow students to explore the syllabus in a way that is free and meaningful to the individual? If we can find a way to do this, then learning really becomes magical.

While there is the usual stretch and challenge, meta-questions, challenge reading, and more, the main thrust of our more able provision in the religious studies (RS) department at SMSJ is one which encourages independent research and exploration. Here are several of the more unique ways that we have encouraged and challenged our more able students in RS and across the school, with the aim of developing transferable skills across the curriculum and inspiring a love of learning amongst both students and staff.

1. Papasavitch (our very own made-up language)

We had used activities based on Jangli and Yelrib, made-up languages used at Eton College, to stretch our pupils and give them exciting and unique learning opportunities. These activities were so well received by our pupils; they wanted more. So we developed ‘Papasavitch’, our very own made-up language.

This is partly what I was referring to earlier: if you find something students enjoy doing, give them a space to explore that love; actively create it. To see if your pupils can crack the language, or have a go yourself, try out this sample Papasavitch activity sheet. 2. The RS SMSJ Essay Writing Competition (open to all schools)

In 2018, SMSJ reached out to a number of academics at various universities to lay the foundations of what has become a national competition. We would like to thank Professor R. Price, Dr E. Burns, Dr G. Simmonds, Dr H. Costigane, Dr S. Ryan and Dr S. Law for their support.

Biannually, we invite students from around the UK (and beyond) to enter the competition, which challenges them to write an essay of up to 1,000 words on any area within RS, to be judged by prestigious academics within the field of philosophy, theology and ethics. While we make this compulsory for our RS A-level pupils, we receive copious entries from students in Years 7-11 at SMSJ, and beyond, owing to the range of possible topics and broad interest from students. Hundreds of students have entered to date, including those from top independent and grammar schools around the UK. (Note: submissions should be in English, and only the top five from each school should be submitted.)

You can learn more about the competition – including past and future judges, essay themes, examples of past entries, and details of how to enter – on the SMSJ website. 3. Collaboration and exploration – across and beyond the school

The role of a Head of Department (HoD), as I see it, is to actively seek opportunities for collaboration and exploration – within the school family and beyond into the wider subject community, as well as among the members of the department. At SMSJ, this ethos is shared by HoDs and other staff alike and expressed in a number of ways.

Regular HoD meetings to discuss and seek opportunities for implementing cross-curricular links are a must, and have proven fruitful in identifying and utilising overlap in the curriculum. Alongside this, we run a Teacher Swaps programme where teachers can study each other’s subjects in a tutorial fashion, naturally creating an awareness and understanding of other subjects.

The Humanities Faculty offers a ‘Read Watch Do’ supplementary learning programme for each year group, which runs alongside regular home learning tasks. The former also supports other departments through improved literacy, building cultural capital and exploration via the independent learning tasks.

Looking beyond the school, our partnerships with the K+ and Oxford Horizons programmes help our sixth-formers prepare for university, while mentoring with Career Ready and the Civil Service supports our students to gain new skills from external providers. Our recent launch of The Spotlight, a newspaper run by students at SMSJ, has heralded a collaboration with a BBC Press Team. Again, this shows other opportunities for cross-curricular overlap, as students are directed to report on different departments’ extracurricular enrichment activities. The possibilities are endless, and limited only by our imagination.

To learn more about any of the initiatives mentioned in this blog post, and/or to share what’s working in your own department/school, please contact communications@nace.co.uk.

Tags:

aspirations

CEIAG

collaboration

creativity

enrichment

free resources

independent learning

KS3

KS4

motivation

philosophy

writing

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Robin Bevan,

08 March 2021

|

Dr Robin Bevan, Headteacher, Southend High School for Boys (SHSB)

One of the underlying tests of whether a student has fully mastered a new area of learning is whether they have the capacity to “self-regulate the production of quality responses” in that domain. At its simplest level, this would be knowing whether an answer is right or not, without reference to any third party or expert source. This develops and extends into whether the student can readily assess the validity of the reasoning deployed in replying to a more complex question. And, at its highest level, the student would be able to articulate why one response to a higher-order question is of superior quality than another.

Framed in another way, we teach to ensure that our pupils know how to answer questions correctly, know what makes their responses sound and, ultimately, understand the distinguishing features of the best quality thinking relevant to the context (and, by this I mean far more than just the components of a GCSE mark scheme).

This hierarchy of desired learning outcomes not only provides an implicit structure for differentiating task outcomes, but also gives a strong steer regarding our approaches to feedback for the most able learners. Our intention for our most able learners is that they can reach the highest level of critical understanding with each topic. This is so much more than just getting the answers right and hints at why traditional tick/cross approaches to marking have often proved so ineffective (Ronayne: 1999).

These comments may be couched in different language, but there is a deep resonance between my observations and the clarion call – over two decades ago – for increased formative assessment that was published as Inside the Black Box (Black and Wiliam, 1998):

Many of the successful innovations have developed self- and peer-assessment by pupils as a way of enhancing formative assessment, and such work has achieved some success with pupils from age five upwards. This link of formative assessment to self-assessment is not an accident – it is indeed inevitable.

To explain this, it should first be noted that the main problem that those developing self-assessment encounter is not the problem of reliability and trustworthiness: it is found that pupils are generally honest and reliable in assessing both themselves and one another, and can be too hard on themselves as often as they are too kind. The main problem is different – it is that pupils can only assess themselves when they have a sufficiently clear picture of the targets that their learning is meant to attain. Surprisingly, and sadly, many pupils do not have such a picture, and appear to have become accustomed to receiving classroom teaching as an arbitrary sequence of exercises with no overarching rationale. It requires hard and sustained work to overcome this pattern of passive reception. When pupils do acquire such an overview, they then become more committed and more effective as learners: their own assessments become an object for discussion with their teachers and with one another, and this promotes even further that reflection on one's own ideas that is essential to good learning.

What this amounts to is that self-assessment by pupils, far from being a luxury, is in fact an essential component of formative assessment. Where anyone is trying to learn, feedback about their efforts has three elements – the desired goal, the evidence about their present position, and some understanding of a way to close the gap between the two (Sadler: 1989). All three must to a degree be understood before they can take action to improve their learning. (Black & Wiliam, 1998)

Understanding the needs of the more able: a tragic parody

Sometimes an idea can become clearer when we examine its opposite: when, that is, we illuminate how the more able learner can be starved of effective feedback. To illustrate this as powerfully as possible, I am going to employ a parody. It is a tragic parody, in that the disheartening description of teaching and learning that it includes is both frustratingly common and yet so easily amenable to fixing. Imagine the following cycle of teacher and pupil activity.

- The teacher identifies an appropriate new topic from the scheme of work. She delivers an authoritative explanation of the key ideas and new understanding. It is an accomplished exposition and the class is attentive.

- A set of response tasks are set for the class. These are graduated in difficulty. Every pupil is required to work in silence, unaided – after all, it has just been explained to them all! Each pupil starts with the first question and continues through the exercise. The work is completed for homework.

- The teacher collects in the homework, marks the work for accuracy of answers with a score out of 10.

- In the next lesson, the class is given oral feedback by the teacher on the most common errors. The class proceeds to the next topic. The cycle then repeats.

This is probably not far removed from the way in which many of us were taught, when we were at school. Let us examine this parody from the perspective of the more able.

- It is highly likely that the more able pupil already knows something, or a great deal, about this topic. Nonetheless, complicit in this well-rehearsed didactic model, the most able pupil sits through the teacher’s presentation, patiently. A good proportion of this time is essentially wasted.

- Silent working prohibits the development of understanding that comes through vocal articulation and discussion. The initially easy exercise prevents, by its very design, the most able from exploring the implications and higher consequences of the topic. The requirement to complete all the questions, even the most simple, fills the time – unproductively. Then, the whole class faces the challenge of completing the harder questions, unsupported, away from the teacher’s expert assistance. For the most able, these harder questions are probably the richest source of potential new learning. But it is no surprise that for the class as a whole the success rate on the harder questions is limited.

- The most able pupil gains 8 or 9 out of 10; possibly even an ego-boosting 10. The pupil feels good and is inclined to see the task as a success. Meanwhile, all the items that are discussed by the teacher were questions that everyone else got wrong, not the learning that is needed to extend or develop the more able pupil.

- A new topic is started. The teacher has worked hard. The class has been well-behaved. The able pupil has filled their time with active work. And yet, so little has been learned.

Unravelling the parody

This article is intended to focus on the most effective forms of feedback for the more able learner; but it is clear from the parody that we are unlikely to create the circumstances for such high-quality feedback without considering, alongside this, elements such as: the diagnostic assessment of prior learning, structured lesson design, optimal task selection, and effective homework strategies. Each of these, of course, warrants an article of its own.

However, we cannot escape the role of task design altogether in effective feedback. A variety of routine approaches, often suited for homework, allow students to become accustomed to the process of determining the quality of what might be expected of their assignments. For example:

a. Rather than providing marked exemplars, pupils are required to apply the mark scheme to sample finished work. Their marking is then compared (moderated), before the actual standards are established. This ideally suits extended written accounts and practical projects.

b. Instead of following a standard task, pupils are instructed to produce a mark scheme for that task. Contrasting views and key features of the responses are developed; leading to a definitive mark scheme. (It may then be appropriate to attempt the task, or the desired learning may well have already been secured.) This ideally suits essays and fieldwork.

c. These approaches may be adapted by supplying student work to be examined by their peers: “What advice would you give to the student who produced this?” “What misunderstanding is present?” “How would you explain to the author the reasons for their grade?” This ideally suits more complex conceptual work, and lines of reasoning.

d. As a group activity, parallel assignments may be issued: each group being required to prepare a mark scheme for just one allocated task, and to complete the others. Ensuring that the mark schemes have been scrutinised first, the completed tasks are submitted for assessment to the relevant group. This ideally suits examination preparation.

Although these are whole-class activities, they are particularly suited to the more able learner as they give access to higher-order reflective thinking and the tasks are oriented around the issue of “what quality looks like”.

Marking work or just marking time?

Teachers spend extended hours marking pupils’ work. It is a common frustration amongst colleagues that these protracted endeavours do not always seem to bear fruit. There are lots of reasons why we mark, including: to ensure that work has been completed; to determine the quality of what has been done; and to identify individual and common errors for immediate redress.

The list could be extended, but should be reviewed in the light of one pre-eminent question: to what extent does this marking enhance pupils’ learning? The honest answer is that there are probably a fair number of occasions when greater benefit could be extracted from this assessment process.

The observations of Ronayne (1999) illustrate this concern and have clear implications for our professional practice with all learners, but perhaps the most able in particular. In his study, Ronayne found that when teachers marked pupils’ work in the conventional way in exercise books, an hour later, pupils recalled only about one third of the written comments accurately – although they recalled proportionately more of the “constructive” feedback and more of the feedback related to the learning objectives.

Ronayne also observed that a large proportion of written comments related to aspects other than the stated learning objectives of the task. Moreover, the proportion of feedback that was constructive and related to the objectives was greater in oral feedback than written; but as more lengthy oral feedback was given, fewer of the earlier comments were retained by the class. In contrast, individual verbal feedback, as opposed to whole-class feedback, improved the recollection of advice given.

So what then should we do?

It is usually assumed that assessment tasks will be designed and set by the teacher. However, if students understand the criteria for assessment in a particular area, they are likely to benefit from the opportunity to design their own tasks. Thinking through what kinds of activity meet the criteria does, itself, contribute to learning.

Examples can be found in most disciplines: pupils designing and answering questions in mathematics is easily incorporated into a sequence of lessons; so is the process of identifying a natural phenomenon that demands a scientific explanation; or selecting a portion of foreign language text and drafting possible comprehension questions.

For multiple reasons the development of these approaches remains restricted. There is no doubt that teachers would benefit from practical training in this area, and a lack of confidence can impede. However, it is often the case that teachers are simply not convinced of the potency of promoting self-regulated quality expertise.

A study in Portugal, reported by Fontana and Fernandes in 1994, involved 25 mathematics teachers taking an INSET course to study methods for teaching their pupils to assess themselves. During the 20-week part-time course, the teachers put the ideas into practice with a total of 354 students aged 8-14. These students were given mathematics tests at the beginning and end of the course so that their gains could be measured. The same tests were taken by a control group of students whose mathematics teachers were also taking a 20-week part-time INSET course but this course was not focused on self-assessment methods. Both groups spent the same time in class on mathematics and covered similar topics. Both groups showed significant gains over the period, but the self-assessment group's average gain was about twice that of the control group. In the self-assessment group, the focus was on regular self-assessment, often on a daily basis. This involved teaching students to understand both the learning objectives and the assessment criteria, giving them an opportunity to choose learning tasks, and using tasks that gave scope for students to assess their own learning outcomes.

Other studies (James: 1998) report similar achievement gains for students who have an understanding of, and involvement in, the assessment process.

One of the distinctive features of these approaches is that the feedback to the student (whether from their own review, from a peer or from the teacher) focuses on the next steps in seeking to improve the work. It may be that a skill requires practice, it may be that a concept has been misunderstood, that explanations lack depth, or that there is a limitation in the student's prior knowledge.

Whatever form the feedback takes, it loses value (and renders the assessment process null) unless the student is provided with the opportunity to act on the advice. The feedback and the action are individual and set at the level of the learner, not the class.

In a similar vein, approaches to “going through” mock examinations and other tests require careful preparation. Teacher commentary alone, whilst resolving short-term confusion, is unlikely to lead to long-term gains in achievement. Alternatives are available:

i. Pupils can be asked to design and solve equivalent questions to those that caused difficulty;

ii. Pupils can, for homework, construct mark schemes for questions requiring a prose response, especially those which the teacher has identified as having been badly answered;

iii. Groups of pupils (or individuals) can declare themselves “experts” for particular questions, to whom others report for help and to have their exam answers scrutinised.

Again, in each of these practical approaches the most able are positioned close to the optimal point of learning as they articulate and demonstrate their own understanding for themselves or for others. In doing so, they can confidently approach the self-regulated production of quality answers.

Further reading

- Black, P. & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising standards through classroom assessment. School of Education, King’s College, London.

- Fontana, D. and Fernandes, M. (1994). ‘Improvements in mathematics performance as a consequence of self-assessment in Portuguese primary school children’. British Journal of Educational Psychology. Vol. 64 pp407-17.

- James, M. (1998) Using Assessment for School Improvement. Heinemann, Oxford.

- Ronayne, M. (1999). Marking and Feedback. Improving Schools. Vol. 2 No. 2 pp42–43.

- Sadler, R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science. Vol. 18 pp119-144.

From the NACE blog:

Additional support

NACE Curriculum Develop Director Dr Keith Watson is presenting a webinar on feedback on Friday 19 March 2021, as part of our Lunch & Learn series. Join the session live (with opportunity for Q&A) or purchase the recording to view in your own time and to support school/department CPD on feedback. Live and on-demand participants will also receive an accompanying information sheet, providing an overview of the research on effective feedback, frequently asked questions, and guidance on applications for more able learners. Find out more.

Tags:

assessment

feedback

independent learning

metacognition

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Keith Watson FCCT,

27 January 2021

|

Dr Keith Watson, NACE Associate

In recent years many new developments in teaching have been most welcome and have helped the shift towards a more research-informed profession. NACE’s recent report Making space for able learners – Cognitive challenge: principles into practice provides examples of strategies used for the design and management of cognitively challenging learning opportunities, including reference to Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction (2010) which outline many of these strategies.

These principles of instruction are particularly influential in current teaching, which is pleasing to the many good teachers who have been used them for years, although they may not have attached that exact language to what they were doing. These principles are especially helpful for early career teachers, but like all principles they need to be constantly reflected upon. I was always taken by Professor Deborah Eyre’s reference to “structured tinkering” (2002): not wholesale change but building upon key principles and existing practice.

This is where “cutaway” comes in – another of the strategies identified in the NACE report, and one which I would like to encourage you to “tinker” with in your approach to ability grouping and ensuring appropriately challenging learning for all.

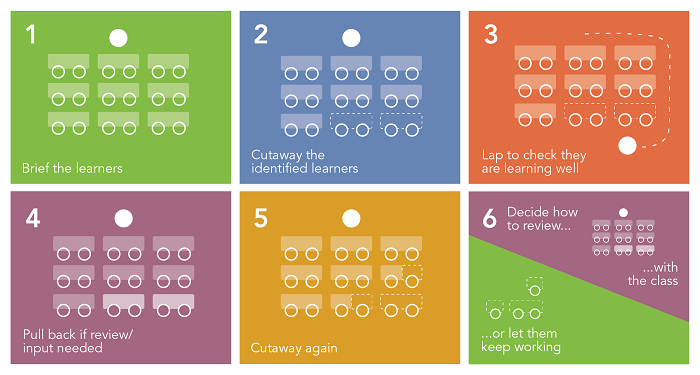

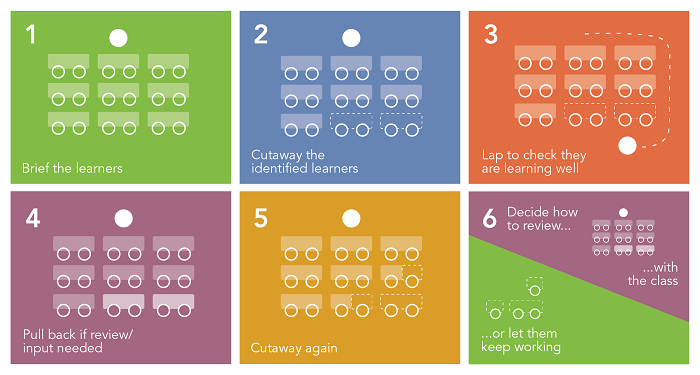

What is “cutaway” and why use it?

The “cutaway” approach involves setting high-attaining students off to start their independent work earlier than the vast majority of the class, while the teacher continues to provide direct instruction/ modelling to the main group. In this way the high attainers can begin their independent work more quickly and can avoid being bored by the whole class instruction which they can find too easy, even when the teacher is trying to “teach to the top”. Once the rest of the class has begun their independent work, the teacher can then focus on the higher attaining group to consolidate the independent work and extend them further.

There are more nuances which I will explain later, but you may wonder, how did this way of working come about?

An often-quoted figure from the National Academy of Gifted and Talented Youth (NAGTY) was that gifted students may already have acquired knowledge of 40-50% of their lessons before they are taught. If I am honest, this was 100% in some of my old lessons! With whole class teaching, retrieval practice tasks and modelling (all essential elements in a lesson), there are clear dangers of pupils being asked to work on things they already know well. There is the issue of what Freeman, (quoted in Ofsted, 2005:3), called the “three-time problem” where: “Pupils who absorb the information the first time develop a technique of mentally switching off for the second and the third, then switching on again for the next new point, involving considerable mental skill.” Why waste this time?

The idea of “cutaway” was consolidated when I carried out a research project involving the use of learning logs to improve teaching provision for more able learners (Watson, 2005). In this project teachers adapted their teaching based on pupil feedback. The teachers realised that, in a primary classroom, keeping the pupils too long “on the carpet” was inappropriate and the length of time available to work at a high level was being minimised. One of the teachers reflected: “Sometimes during shared work on the carpet, when revising work from previous lessons to check the understanding of other pupils, I feel aware of the more able children wanting to move on straight away and find it difficult to balance the needs of all the children within the Year 5 class.”

It therefore became common in lessons (though not all lessons) to cutaway pupils when they were ready to begin independent work. By using “cutaway” the pupils use time more effectively, develop greater independence, can move through work more quickly and carry out more extended and more challenging tasks. The method was commented upon favourably during a HMI inspection that my school received and has ever since been a mainstay of teaching at the school.

Who, when and how to cutaway

So how does a teacher decide when and who to cutaway? The method is not needed in all lessons, the cutaway group should vary based upon AfL, and at its best it involves pupils deciding whether they feel they need more modelling/explanation from the teacher or are ready to be cutaway. In a recent NACE blogpost on ability grouping, Dr Ann McCarthy emphasises that in using cutaway “the teacher constantly assesses pupils’ learning and needs and directs their learning to maximise opportunities, growth and development” and pupils “leave and join the shared learning community”. This underlines the importance of the AfL nature of the strategy and the importance of developing learners’ metacognition, which was another key finding in the NACE report.

Sometimes the cutaway approach is decided on before a lesson by the teacher based upon previous work. In GCSE history, a basic retrieval task on the Norman invasion could be time wasted for a more able pupil who has secure knowledge, whereas being cutaway to do an independent task centred on the role of the Pope in supporting William would be more challenging and worthwhile. It comes down to one key question a teacher needs to ask themselves when speaking to the whole class: “Who do I need here now?” Who needs to retrieve this knowledge? Who needs to hear this explanation? Who needs to see this model or complete this example? If a small group of higher attainers do not need this, then why slow the pace of their learning? Why not start them either on the same work independently or more challenging work to accelerate learning?

Why not play around with this idea? Explain your thinking to the pupils and see how they respond. Sometimes, at the end of one lesson, a task for the next lesson can be explained and the pupils could start the next lesson by working on that task straight away. The 2015 Ofsted handbook said, “The vast majority of pupils will progress through the programmes of study at the same rate”, and ideally, they will. However, a few pupils will progress at a faster rate and therefore need adapted provision. The NACE research and accompanying CPD programme suggests the use of “cutaway” can achieve this and it is well worth all teachers doing some “structured tinkering” with this strategy.

References

Additional reading and support

Share your views

How do you use ability grouping, and why? Share your experiences by commenting on this blog post or by contacting communications@nace.co.uk

Tags:

cognitive challenge

differentiation

grouping

independent learning

pedagogy

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|