Guidance, ideas and examples to support schools in developing their curriculum, pedagogy, enrichment and support for more able learners, within a whole-school context of cognitively challenging learning for all. Includes ideas to support curriculum development, and practical examples, resources and ideas to try in the classroom. Popular topics include: curriculum development, enrichment, independent learning, questioning, oracy, resilience, aspirations, assessment, feedback, metacognition, and critical thinking.

Top tags:

pedagogy

questioning

enrichment

research

independent learning

oracy

curriculum

aspirations

free resources

KS3

cognitive challenge

KS4

assessment

language

literacy

critical thinking

feedback

metacognition

resilience

collaboration

English

maths

confidence

creativity

wellbeing

lockdown

vocabulary

access

mindset

problem-solving

|

Posted By Lol Conway,

06 May 2025

|

Lol Conway, Curriculum Consultant and Trainer for the Design and Technology Association

Throughout my teaching, inclusivity has always been at the forefront of my mind – ensuring that all students can access learning, feel included, and thrive. Like many of my fellow teachers, at the start of my teaching career my focus was often directed towards supporting SEND or disadvantaged students, for example. I have come to realise, to my dismay, that more able students were not high up in my consideration. I thought about them, but often as an afterthought – wondering what I could add to challenge them. Of course, it should always be the case that all students are considered equally in the planning of lessons and curriculum progression and this should not be dictated by changes in school data or results. Inclusivity should be exactly that – for everyone.

True inclusivity for more able students isn’t about simply adding extra elements or extensions to lessons, much in the same way that inclusivity for students with learning difficulties isn’t about simplifying concepts. Instead, it’s about structuring lessons from the outset in a way that ensures all students can access learning at an appropriate level.

I realised that my approach to lesson planning needed to change to ensure I set high expectations and included objectives that promoted deep thinking. This ensured that more able students were consistently challenged whilst still providing structures that supported all learners. It is imperative that teachers have the confidence and courage to relentlessly challenge at the top end and are supported with this by their schools.

As a Design and Technology (D&T) teacher, I am fortunate that our subject naturally fosters higher-order thinking, with analysis and evaluation deeply embedded in the design process. More able students can benefit from opportunities to tackle complex, real-world problems, encouraging problem-solving and interdisciplinary connections. By integrating these elements into lessons, we can create an environment where every student, including the most able, is stretched and engaged. However, more often than not, these kinds of skills are not always nurtured at KS3.

Maximizing the KS3 curriculum

The KS3 curriculum is often overshadowed by the annual pressures of NEA and examinations at GCSE and A-Level, often resulting in the inability to review KS3 delivery due to the lack of time. However, KS3 holds immense potential. A well-structured KS3 curriculum can inspire and motivate students to pursue D&T while also equipping them with vital skills such as empathy, critical thinking, innovation, creativity, and intellectual curiosity.

To enhance the KS3 delivery of D&T, the Design and Technology Association has developed the Inspired by Industry resource collection – industry-led contexts which provide students with meaningful learning experiences that go beyond theoretical knowledge. We are making these free to all schools this year, to help teachers deliver enhanced learning experiences that will equip students with the skills needed for success in design and technology careers.

By connecting classroom projects to real-world industries, students gain insight into the practical applications of their learning, fostering a sense of purpose and motivation. The focus shifts from achieving a set outcome to exploring the design process and industry relevance. This has the potential to ‘lift the lid’ on learning, helping more able learners to develop higher-order skills and self-directed enquiry.

These contexts offer a diverse range of themes, allowing students to apply their knowledge and skills in real-world scenarios while developing a deeper understanding of the subject and industry processes. Examples include:

- Creating solutions that address community issues such as poverty, education, or homelessness using design thinking principles to drive positive change;

- Developing user-friendly, inclusive and accessible designs for public spaces, products, or digital interfaces that accommodate people with disabilities;

- Designing eco-friendly packaging solutions that consider materials, manufacturing processes, and end-of-life disposal.

These industry-led contexts foster independent discovery and limitless learning opportunities, particularly benefiting more able students. By embedding real-world challenges into the curriculum, we can push the boundaries of what students can achieve, ensuring they are not just included but fully engaged and empowered in their learning journey.

Find out more…

NACE is partnering with the Design & Technology Association on a free live webinar on Wednesday 4 June 2025, exploring approaches to challenge all learners in KS3 Design & Technology. Register here.

Tags:

access

cognitive challenge

creativity

design

enquiry

free resources

KS3

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

problem-solving

project-based learning

technology

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Andy Griffith,

04 December 2024

|

Schools are tasked by Ofsted to “boost cultural capital” and to “close the disadvantage gap”. In this blog post, Andy Griffith, co-author of The Working Classroom, makes some practical suggestions for schools to adopt.

1. Explore the language around “cultural capital” and “disadvantage”

As educators we know that language is very important, so before we try to boost or close something we should think deeply about terms that are commonly referred to. What are the origins of these terms? What assumptions lie behind them? Ofsted describes cultural capital as “the best that has been thought and said”, but who decides what constitutes the “best”? Notions of best are, by definition, subjective value choices.

The phrase “best that has been thought and said”, originally coined by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, is worthy of study in itself (see below for reference). Bourdieu described embodied cultural capital as a person’s education (knowledge and intellectual skills) which provides advantage in achieving a higher social status. For Bourdieu the “game” is rigged. The game Bourdieu refers to is, of course, the game of life, of which education is a significant element.

When it comes to the term “disadvantaged”, Lee Elliott Major, Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter Professor, suggests that instead we refer to low-income families as “under-resourced”. Schools should be careful not to treat the working class as somehow inferior or as something that needs to be fixed.

Action: Ensure that staff fully understand the term “cultural capital”. Alongside this, explore “social capital” and “disadvantage”. This is best done through discussion and debate. Newspaper articles and even blogs like this one can act as a good stimulus.

2. Create a well-designed cultural curriculum

Does your school have a plan for taking students on a cultural journey? How many trips will your students go on before they leave your school? Could these experiences be incorporated into a passport of sorts?

The cultural experiences you offer will be determined by factors such as your school’s location and budget. A lot of cultural experiences can be delivered in-house in the form of external speakers, films and documentaries, or virtual reality. Others will require excursions. In either case, creating a Cultural Passport helps staff to plan experiences that complement and supplement previous experiences.

Schools should strike a balance between celebrating each community’s history and going beyond the existing community to broaden students’ horizons. Again, language is important. Does your school’s cultural curriculum explore the differences between so-called “high” and “low” culture?

No class is an island. Students of all social backgrounds should experience live theatre, visiting museums, going to art exhibitions, visiting the countryside and encountering people from cultures other than their own. Equally, every school’s cultural curriculum should celebrate working class culture. The working classes have a vibrant history of creating art, music, theatre, literature and so on, which needs to be reflected in the core curriculum.

By looking through the lens of race and gender, most schools have a more diverse offering of writers compared with when I went to school. It is right that more Black voices and more female voices are represented in the school curriculum. This opens new insights for readers, as well as providing Black and female students with more role models.

Similarly, there should be a strong emphasis on the work of working-class artists and autodidacts, no matter the social demographic of the school. Studying working-class writers such as Jimmy McGovern, Kayleigh Lewellyn, and musicians such as Terry Hall and even Dolly Parton can be inspiring. Similarly, learning about autodidacts such as Charles Dickens, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Vincent Van Gogh and Frida Kahlo can teach students that where there is a strong desire to learn, people can find a way.

Action: Ensure your school is “teaching backwards” from rich cultural experiences. Outline the experiences that will be stamped in their Cultural Passport before they leave your school.

3. Explore social capital barriers for students

One of the greatest things we can do as educators is to remove a barrier that is holding a student back. One barrier that is faced by many working-class students is lack of social capital – i.e. the limited range of occupations of their social acquaintances or network.

In 2016 I created the first of a number of Scholars Programmes in Kirkby, Merseyside. I’m proud that as well as making a positive impact on academic results at GCSE, it has raised aspirations. The programme is deliberately designed to build social capital. Over the duration of the programme (from Year 7 to 11), students have opportunities to meet and interview adults who are in careers that they aspire to. As well as work experience, the school organises Zoom interviews for students with people working in the industry that they are interested in joining. Not only do these interviews invigorate students, they create a contact that is there to be emailed for information and advice. Over time, the school has created a database of contacts who are able to offer work placements or are happy to take part in either face-to-face or virtual interviews with students. These people are friends and family members of the staff, and even friends of friends.

It is much, much harder for working class students to enter elite professions such as medicine, law and the media. The arts and the creative industries are also harder to break into. Contacts who are able to help a student to build specific industry knowledge and experience can give them a better chance of future success.

Action: Creatively utilise a database of school contacts to provide information and advice for students. Match students with professionals who can offer career advice and insights.

Reference: P. Bourdieu, Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction. In J. Karabel and A. H. Halsey (eds), Power and Ideology in Education (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977), pp. 487–51.

The ideas and strategies in this article are contained within The Working Classroom by Matt Bromley and Andy Griffith (Crown House Publishing). More information about the book and training around its contents can be found here.

NACE members can benefit from a 20% discount on all purchases from the Crown House Publishing website. View our member offers page for details.

Plus... The NACE Conference 2025 will draw on the latest research (including our own current research programme) and case studies to explore how schools can remove barriers to learning and create opportunities for all young people to flourish. Read more and book your place.

Tags:

access

aspirations

CEIAG

disadvantage

diversity

enrichment

mentoring

myths and misconceptions

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Claire Gadsby,

16 January 2023

|

Claire Gadsby, educational trainer, author and founder of Radical Revision, shares five practical approaches to make your students’ revision more effective.

Did you know that 88% of pupils who revise effectively exceed their target grade? Interestingly, most pupils do not know this and fail to realise exactly how much of a gamechanger revision really is. Sitting behind this simple-looking statement, though, lies the key question: what is effective revision?

In my revision work with thousands of pupils around the world, I have not met many who are initially overjoyed at the thought of revision, often perceiving it as an onerous chore to be endured on their own before facing the trial of the exams. It does not have to be this way and I am passionate about taking the pain out of the process.

Revision can – and should – be fun. Yes, you read that right. The following strategies may be helpful for you in motivating and supporting your pupils on their revision journey.

1. Timer challenge

Reassure your pupils that not everything needs revising: lots is actually still alive and well in their working memory. Put a timer on the clock and challenge pupils to see how much they can recall about a particular topic off the top of their head in just five minutes. The good news is that this is ‘banked’: now what pupils need to do is to focus their revision on the areas they did not write down. It is only at this point that they need to start scanning through notes to identify things they had missed.

2. Bursts and breaks

It is quite common for young people to feel overwhelmed by the sheer amount of revision. Be confident when you reassure them that ‘little and often’ really is the best way to tackle it. Indeed, research suggests that a short burst of 25 minutes revision followed by a five-minute break is the ideal. Make the most of any ‘dead time’ slots in the school day to include these short revision bursts.

3. Better together

Show pupils the power of collaborative revision. Working with at least one other person is energising and gets the job done quicker. Activities such as ‘match the pairs’ or categorising tasks have the added advantage of also promoting higher-order thinking and discussion.

4. Take the scaffolds away

It is not effective to simply keep reading the same words during revision. Instead, ‘generation’ is one of the key strategies proven to support long-term learning. Tell pupils not to write out whole words in their revision notes. Instead, they should write just the first letter of key words and then leave a blank space. When they look back at their notes, their brain will be challenged to work harder to recall the rest of the missing word which, in turn, makes it more likely to be retained for longer.

5. Playful but powerful

We know that low-stakes quizzing is ideal, and my ‘lucky dip’ approach is helpful here. Keep revision information, such as key terms and concepts, ‘in play’ by placing them in a gift bag or similar. Mix these up and pull one out at random to check for understanding. Quick, out of context, checks like this are a type of inter-leaving which is proven to strengthen recall.

Following feedback from pupils and their parents that they would benefit from more sustained support and structure in the lead up to their exams, in 2021 I launched Radical Revision – an online revision programme for schools with short video tutorials (ideal for use in tutor time) to introduce students to our cutting-edge revision techniques. The online portal also contains a plethora of downloadable resources and CPD for teachers, as well as resources and webinars for parents. For more information please visit the Radical Revision website, where you can sign up to access a free trial version. We’re also offering NACE members a 15% discount on the cost of an annual subscription for your school – log in to the NACE member offers page for details.

Sources: National strategies GCSE Booster materials, DfES publications 2003.

For even more great practical ideas from Claire, join us the NACE annual conference on 20 June 2023 – details coming soon!

Tags:

assessment

collaboration

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

retrieval

revision

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

14 February 2022

|

Dr Ann McCarthy, NACE Research and Development Director

It may seem strange to find an article with both metacognition and assessment in the title. Many people still view assessment as an activity which is separate from the art of teaching and is simply a list of checks and balances required by the education system to set targets, track learning, report to stakeholders and finally to issues qualifications. However, for those who are using assessment routinely, and at all points within the act of teaching and learning, they know the power of assessment which is both explicit and implicit within the process. The drive to focus on metacognition, for all ages of pupils, has opened opportunities for assessment practices to be developed within the classroom both by the teacher and by the pupils themselves.

Contents:

The story so far: summative and formative assessment

Historically, assessment processes were strongly linked to the curriculum and planned content because they responded to an education system which prepared pupils for endpoint examinations. This approach is still evident within the many summative assessments, tests of memory or vocabulary and algorithmic routines seen in classrooms today. One can understand the reliance on these practices as they lead to the maintenance of a school’s grade profile and with good teaching and leadership can promote improvements in external measures. It feels safe!

The strength of this type of assessment is that it can provide baseline markers or diagnostic information. Here the assessment focus is always linked to the curriculum, the content and the examination. Good teaching can then move pupils closer to the end goal. When pupils respond well to this style, they can gain the required results – but too often pupils do not respond well and do not necessarily develop beyond the limits of the examination style question. Here the agenda is owned by the teacher, with pupils expected to respond to the demands of the model.

The weakness of this style of assessment is that there is little space for variation to reflect the personalities and learning styles of pupils or to allow more able pupils to learn beyond the examination. Here pupils are trained to meet the end goal without necessarily seeing the potential of the learning beyond the final grade. How often do we hear people say “I can’t do this” or “I don’t know this” although it may be a subject studied in school?

The development of formative assessment in different teaching contexts has increased teachers’ understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies alongside subject-specific skills and content. However, teachers can still be drawn into summative assessment practices in the guise of formative assessment. These are often recall or memory activities or small-scale versions of summative assessments aligned to endpoint assessment.

Good formative assessment is embedded in the planning for teaching and classroom practice. An understanding of the assessment measures and effective feedback will enable pupils to take some ownership of their learning. However, in a cognitively challenging learning environment we seek to empower pupils to own their learning and to become resilient, independent learners. So how then can we think differently about assessment practice?

Limitations to traditional formative and summative assessment practices

With traditional summative and formative assessment methods pupils are responsive to the demands and expectations of the teacher. They are expected to act in response to assessment outcomes and teacher feedback, using the methods and strategies modelled or directed by the teacher. The teacher plans the content, makes a judgement and creates opportunities to gain experience within the planned model. The teacher then assesses within this model and offers advice to the pupils about what they must do next and the actions which the teacher believes will lead to better learning and outcomes.

This can be successful in achieving the endpoint grades or examination standards. It does not necessarily develop pupils’ ability to do this for themselves, both within and beyond the education system.

Developing cognition and cognitive strategies

At the heart of good teaching and learning there is a focus on mental processes (cognition) and skills (cognitive strategies). The most effective classroom assessment makes use of cognition and the cognitive strategies beneficial to the specialist subject, which are most appropriate for the pupils.

The teacher of more able pupils aims to create cognitively challenging learning experiences, which must not be adversely affected by the assessments. This requires carefully selected strategies which hone the cognitive processes at the same time as developing subject expertise. Teaching builds from what pupils already know and understand, what they need to learn and what they have the potential to achieve. It develops the skills needed to apply knowledge, understanding and learning in a variety of contexts.

To maximise the impact of planned teaching on learning, effective assessment practices are essential. An important factor when planning for assessment, which goes beyond the confines of endpoint limitations, is that it places the pupil, rather than the content, at the centre of the process. Assessment activities should not simply measure current performance against a list of content-driven minimum standards, but also lead to a greater depth of knowledge and improved cognition. These assessments are not positioned separately from the learning but are at the heart of the learning and the development of cognitive strategies.

Assessments planned as part of – and not separate from – teaching and learning might include:

- High-quality classroom dialogic discourse;

- Big Questions;

- Teacher-pupil, pupil-teacher and pupil-pupil questioning;

- Collaborative pursuits aimed to generate new ideas;

- Adopting learning roles to enhance and extend current skills;

- Problem solving;

- Prioritisation tasks;

- Research;

- Investigations;

- Explaining and justifying responses;

- Analytical tasks;

- Examining misconceptions;

- Recall for facts in novel contexts;

- Organisation of knowledge to develop new ideas.

By examining learning in the moment, with pupils working independently or together on pre-planned tasks, with clear and measurable success criteria, the teacher can assess more accurately. Using the planned teaching and learning repertoire as the assessment, the teacher makes learning visible. The teacher will gain a greater understanding of the teaching models which lead to greater improvements in cognition. The teacher is then also able to establish which cognitive strategies are used most effectively and which need to be developed.

By maintaining the learning while assessing the teacher acts as a resource and a learning activator. Timely questions, redirecting actions or thoughts and providing feedback are among the variety of actions which can take place in the instant. This does not prevent an analysis of the level of knowledge or understanding of the subject. By working in this way, the teacher can provide more precise input to either the individual or the class; in the moment, it will have the greatest benefit.

In classrooms where the teacher combines their subject knowledge with their understanding of cognition, they will inevitably understand the nature and power of appropriate assessment. Teaching and assessment which is rooted in an understanding of cognition has the potential to prepare pupils for learning both within and beyond the classroom.

When the nature of the learning, the tasks and the assessments are shared with the pupils, they can begin to take ownership of their learning and develop their skills under the guidance of the teacher. Assessing through an understanding of cognition and cognitive strategies allows the teacher to share more fully the process of learning both in terms of academic outcomes but also in relation to thought and cognitive strategies. The pupils can now more fully impact on their own learning, but there is still a dependency on the teacher’s feedback and planning.

Once we appreciate the power of cognitively aware teaching, learning and assessment then we realise that pupils can take action to improve their thinking and learning if they know more. Metacognition means that pupils have a critical awareness of their own thinking and learning. They can visualise themselves as thinkers and learners. If the assessment, teaching and learning model moves the learner towards owning the learning, understanding their own cognition and cognitive strategies, then greater short-term and long-term gains can be made. Developing metacognitively focused classrooms will lead to a better quality of assessment which pupils will understand and can interrogate to refine their own learning.

When teachers look to develop metacognition as a whole-school strategy and within individual subject teaching there can be greater gains. The pupils will learn about the process of learning and come to understand ways in which they can best improve their own learning. Metacognition is about the ways learners monitor and purposefully direct their learning. If pupils develop metacognitive strategies, they can use these to monitor or control cognition, checking their effectiveness and choosing the most appropriate strategy to solve problems.

When planning teaching which makes use of metacognitive processes the teacher must first help pupils to develop specific areas of knowledge.

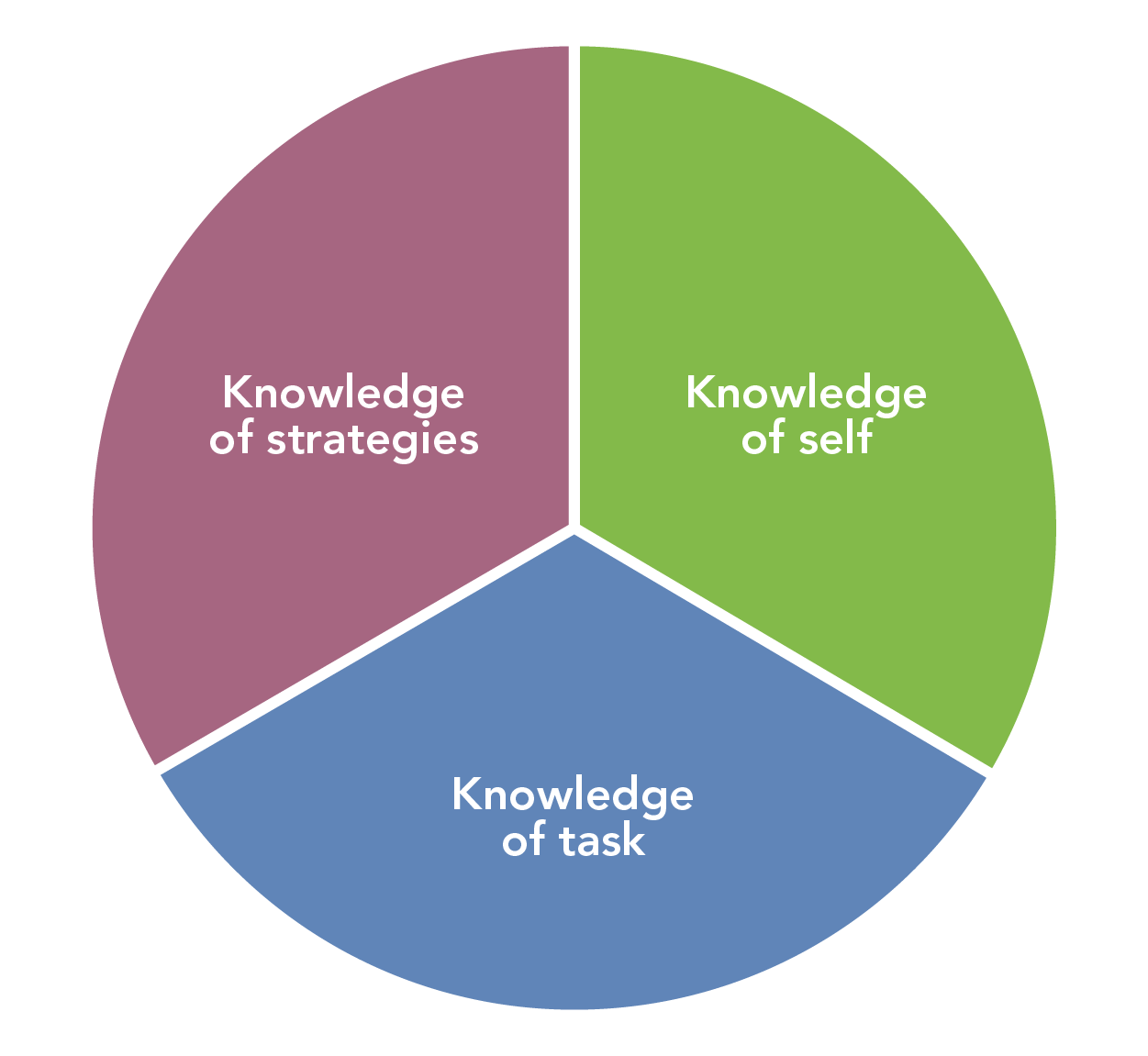

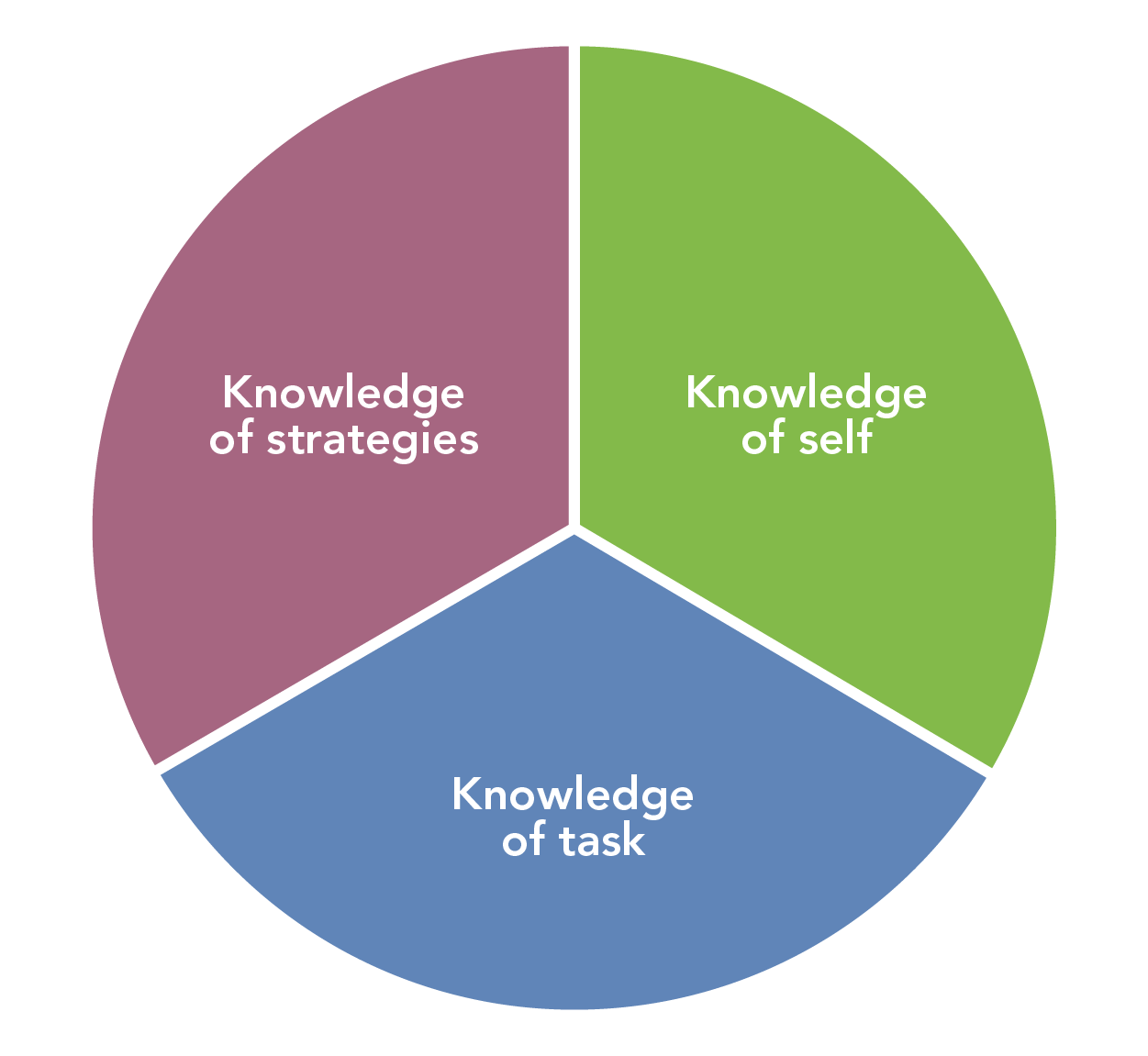

Metacognitive knowledge refers to what learners know about learning. They must have a knowledge of:

- Themselves and their own cognitive abilities (e.g. I find it difficult to remember technical terms)

- Tasks, which may be subject-specific or more general (e.g. I am going to have to compare information from these two sources)

- The range of different strategies available, and an ability to choose the most appropriate one for the task (e.g. If I begin by estimating then I will have a sense of the magnitude of the solution).

Metacognitive knowledge must be explicitly taught within subjects. Where the assessment process works effectively within this the pupils can measure and understand their own learning. This is particularly important for more able learners who are then able to take greater responsibility for their learning, moving this beyond the constraints of the examined curriculum.

The Fisher-Frey Model shows how responsibility for learning moves from teacher to pupils through carefully planned teaching strategies. This model is also relevant to the development of metacognitive teaching strategies as they are developed within schools. The Education Endowment Foundation has shown how the teacher can learn about and teach metacognitive strategies, gradually passing the learning to the pupils.

Diagram based on work of Fisher-Frey and EEF

At each stage some form of assessment takes place to ensure the required or expected outcomes have been achieved. The teacher wants to know the impact of the teaching and the pupils want to know the effectiveness of their learning. The teacher must also assess the pupils’ ability to use metacognitive strategies. Are they simply accepting the situation as it is? Are they attempting to engage in the process but do not know which strategy is best? Are they able to use their learning strategically or have they moved on to become reflective and independent learners? The teacher uses the assessment information with the pupil to help them to become increasingly self-aware and more adept at using the strategies available to them, but also to recognise their own strengths.

Strategies used in metacognitively focused classrooms which can be developed with the teacher’s support, undertaken by pupils and assessed might include:

- Prioritising tasks

- Creating visual models such as bubble maps and flow diagrams

- Questioning

- Clarifying details of the task

- Making predictions

- Summarising information

- Making connections

- Problem solving

- Creating schema

- Organising knowledge

- Rehearsing information to improve memory

- Encoding

- Retrieving

- Using learning and revision strategies

- Using recall strategies

If pupils and teachers work together to assess and plan the process of learning about the things they need to know and about themselves as learners, then metacognitive self-regulation becomes possible. Metacognitive regulation refers to what learners do about learning. It describes how learners monitor and control their cognitive processes. Pupils can then learn through a cyclic process in which they learn how to plan, monitor and evaluate both what they learn and how they learn.

Based on diagram in Getting Started with Metacognition, Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team

Pupils need to know how to work through these crucial stages to be successful in their academic work and in support of their metacognitive processes. For example, a learner might realise that a particular strategy is not achieving the results they want, so they decide to try a different strategy. Assessment information will help them to refine the strategies they use to learn. They will use this to evaluate their subject knowledge, metacognitive knowledge and metacognitive regulation. They will become more motivated to engage in learning and can develop their own strategies and tactics to enhance their learning.

Conclusion: the potential of metacognition to enhance assessment, teaching and learning

If teaching is focused on subject content and only subject content is assessed, then teachers will be able to plan, track, set targets and work towards examination grades.

When a teacher is knowledgeable about cognition and cognitive strategies, teaching and learning becomes more interesting. The teacher begins to share the objectives and success criteria with the pupils. Planning for teaching and the learning activities develop cognition and move beyond simple recall and application of facts. Pupils become more able to use and organise information. They are more able to retain knowledge and use it in a variety of complex or original contexts. The teacher remains in control of the planning, teaching and assessment but pupils have some degree of understanding of this. They are now more able to respond to advice about their learning. They begin to try alternative methods for learning. They know what they are doing well, what they still need to do, how they need to do this and why it is important. They utilise the assessment criteria and feedback to enhance their learning.

Teachers who teach pupils about metacognition and help them to develop metacognitive awareness know the importance of giving control to the pupil. They collaborate with the pupils to assess their development in becoming more strategic or reflective in the use of strategies. Pupils learn better because they begin to assess their own learning strategies and their subject knowledge with a plan, monitor and evaluate model. Their motivation improves and the conversations between teachers and their pupils about learning are more insightful.

Call for contributions: share your school’s experience

In this article I highlight the importance of metacognition for learning and for the learner. I also explain the importance of assessing what is happening in the classroom. Assessment will give the teacher a clear indication of the impact of teaching and the effectiveness of learning. Assessment will help the self-regulated learner to reflect on their learning and develop the strategies needed to be a successful learner throughout life.

We are seeking NACE member schools to contribute to our work in this area by sharing information about effective assessment approaches in their contexts. Where has assessment practice been implicit within your teaching? How was it planned? How did if fit within the teaching? How was the process shared with the pupils? How did you and the pupils measure levels of achievement? How did this change the way they learned or the way you taught?

If you can share examples of the way you have built up assessment processes within the classroom and across the school, we would love to hear from you.

Please contact communications@nace.co.uk for more information, or complete this short online form to register your interest.

Read more: Planning effective assessment to support cognitively challenging learning

Connect and share: join fellow NACE members at our upcoming member meetup on the theme "rethinking assessment" – 23 March 2022 at New College, Oxford – to share ideas and examples of effective assessment practices. Details and booking

References and additional reading

- Anderson, Neil J. (2002). The Role of Metacognition in Second Language Teaching and Learning. ERIC Digest.

- Cahill, H. et al (2014). Building Resilience in Children and Young People: A Literature Review for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. DEECD.

- Cambridge International Education Teaching and Learning Team. Getting Started with Metacognition.

- Chick, N. (2013). Metacognition. Centre for Teaching, Vanderbilt University.

- Education Endowment Foundation (2018). Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: Seven recommendations for teaching self-regulated learning & metacognition

- EEF. Evidence Summaries: Metacognition and Self-Regulation

- EEF. Four Levels of Metacognitive Learners (Perkins, 1992)

- EEF. Metacognition and Self-Regulated Learning: School Audit Tool

- EEF (Muijs D., Bokhove C., 2020). Metacognition and Self-Regulation Review

- EEF (Quigley, A., Muijs, D., & Stringer, E., 2020). Metacognition & Self-Regulated Learning Guidance Report

- Fisher, D. & Frey, N. (2008). Better Learning Through Structured Teaching: A framework for the gradual release of responsibility. ASCD.

- Lowe, H. and McCarthy, A. (2020). Making Space for Able Learners – Cognitive Challenge: Principles into Practice. NACE.

- Webb, J. (2021). Extract from The Metacognition Handbook. John Catt Educational.

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

metacognition

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ems Lord,

11 February 2022

|

Dr Ems Lord, Director of the University of Cambridge’s NRICH initiative, shares three activities to try in your classroom, to help learners improve their use of mathematical vocabulary.

Like many academic subjects, mathematics has developed its own language. Sometimes this can lead to humorous clashes when mathematicians meet the real world. After all, when we’re calculating the “mean”, we’re not usually referring to a measurement of perceived nastiness (unless it’s the person who devised the problem we’re trying to solve!).

Precision in our use of language within mathematics does matter, even among school-aged learners. In my experience, issues frequently arise in geometry sessions when working with pyramids and prisms, squares and rectangles, and cones and cylinders. You probably have your own examples too, both within geometry and the wider curriculum.

In this blog post, I’ll explore three tried-and-tested ways to improve the use of mathematical vocabulary in the classroom.

1. Introduce your class to Whisper Maths

“Prisms are for naughty people, and pyramids are for dead people.” Even though I’ve heard that playground “definition” of prisms and pyramids many times before, it never fails to make me smile. It’s clear that the meanings of both terms cause considerable confusion in KS2 and KS3 classrooms. Don’t forget, learners often encounter both prisms and pyramids at around the same time in their schooling, and the two words do look very similar.

One useful strategy I’ve found is using an approach I like to refer to as Whisper Maths; it’s an approach which allows individuals time to think about a problem before discussing it in pairs, and then with the wider group. For Whisper Maths sessions focusing on definitions, I tend to initially restrict learner access to resources, apart from a large sheet of shared paper on their desks; this allows them to sketch their ideas and their drawings can support their discussions with others.

This approach helps me to better understand their current thinking about “prismness” and “pyramidness” before moving on to address any misconceptions. Often, I’ve found that learners tend to base their arguments on their knowledge of square-based pyramids which they’ve encountered elsewhere in history lessons and on TV. A visit to a well-stocked 3D shapes cupboard will enable them to explore a wider range of examples of pyramids and support them to refine their initial definition.

I do enjoy it when they become more curious about pyramids, and begin to wonder how many sides a pyramid might have, because this conversation can then segue nicely into the wonderful world of cones!

2. Explore some family trees

Let’s move on to think about the “Is a square a rectangle?” debate. I’ve come across this question many times, and similarly worded ones too.

As someone who comes from a family which talks about “oblongs”, I only came across the “Is a square a rectangle?” debate when I became a teacher trainer. For me, using the term oblong meant that my understanding of what it means to be a square or an oblong was clear; at primary school I thought about oblongs as “stretched” squares. This early understanding made it fairly easy for me to see both squares and oblongs (or non-squares!) as both falling within the wider family of rectangles. Clearly this is not the case for everyone, so having a strategy to handle the confusion can be helpful.

Although getting out the 2D shape box can help here, I prefer to sketch the “family tree” of rectangles, squares and oblongs. As with all family trees, it can lead to some interesting questions when learners begin to populate it with other members of the family, such the relationship between rectangles and parallelograms.

3. Challenge the dictionary!

When my classes have arrived at a definition, it’s time to pull out the dictionaries and play “Class V dictionary”. To win points, class members need to match their key vocabulary to the wording in the dictionary. For the “squares and rectangles” debate, I might ask them to complete the sentence “A rectangle has...”. Suppose they write “four sides and four right angles”, we would remove any non-mathematical words, so it now reads “four sides, four right angles.” Then we compare their definition with the mathematics dictionary.

They win 10 points for each identical word or phrase, so “four right angles, four sides” would earn them 20 points. It’s great fun, and well worth trying out if you feel your classes might be using their mathematical language a little less imprecisely than you would like.

More free maths activities and resources from NRICH…

A collaborative initiative run by the Faculties of Mathematics and Education at the University of Cambridge, NRICH provides thousands of free online mathematics resources for ages 3 to 18, covering early years, primary, secondary and post-16 education – completely free and available to all.

The NRICH team regularly challenges learners to submit solutions to “live” problems, choosing a selection of submissions for publication. Get started with the current live problems for primary students, live problems for secondary students, and live problems for post-16 students.

Tags:

free resources

language

maths

myths and misconceptions

pedagogy

problem-solving

vocabulary

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Ann McCarthy,

06 October 2021

|

NACE Research & Development Director Dr Ann McCarthy shares key principles for effective assessment planning and practice, within cognitively challenging learning environments.

Following two academic years of uncertainty and alternative arrangements for teaching and assessment, the conversation regarding testing and assessment has become increasingly important. Upon return to the routines of day-to-day classroom teaching, schools have had to find ways to assess knowledge, progress and understanding achieved through distance learning or redesigned classroom practices. For older pupils there has been a need to provide evidence to examination boards to secure grades and guarantee appropriate progression routes. This inherent need to provide checks and balances before pupils’ achievement is recognised can become a distraction from the art of teaching. In fact, Rimfield et al (2019) found a very high agreement between teacher assessments and exam grades in English, maths, and science.

- Could we examine less often and use classroom-based assessment more often?

- Should we rethink testing and assessment and their position in the learning process?

Testing vs assessment

The terms test and assessment are often used interchangeably, but in the context of education we need to recognise the difference. A test is a product which is not open to interpretation; it uses learning objectives and measures success achieved against these. Teachers use tests to measure what someone knows or has learned. These may be high-stakes or low-stakes events. High-stakes tests may lead to a qualification, grading or grouping, whereas low-stakes tests can support cognition and learning. Testing takes time away from the process of learning and as such testing should be used sparingly, when necessary and when it contributes significantly to the next steps in teaching or learning.

Assessment, by contrast, is a systematic procedure which draws on a range of activities or evidence sources which can then be interpreted. Regardless of the position teachers hold regarding the use of testing and examinations, meaningful assessment remains an essential part of teaching and learning. Assessment sits within curriculum and pedagogy, beginning with diagnostic assessment to plan learning which best reflects the needs of the learner. A range of formative assessment activities enable the teacher and pupils to understand progress, improve learning and adapt the learning to reflect current needs. Endpoint activities can be used as summative assessments to appreciate the degree to which knowledge has been acquired, alongside varied and complex ways in which that knowledge can be used.

Assessment might be viewed in three different ways: assessment of learning; assessment for learning; and assessment as learning. The choice of assessment practice will then impact on its use and purpose. Regardless of the process chosen and the procedures used, the teacher must remember that the value of the assessment is in the impact it has on pedagogy and practice and the resulting success for the pupils, rather than as an evidence base for the organisation.

NACE research has shown that cognitively challenging experiences – approaches to curriculum and pedagogy that optimise the engagement, learning and achievement of very able young people – will have a significant and positive impact on learning and development. But how can we see this working, and what role does assessment play? When planning for cognitively challenging learning, assessment planning should reflect the priorities for all other aspects of learning.

A strategic approach to assessment which supports cognitively challenging learning environments

When considering the place of assessment in education, teachers must be clear about:

- What they are trying to assess;

- How they plan to assess;

- Who the assessment is for;

- What evidence will become available;

- How the evidence can be interpreted;

- How the information can then be used by the teacher and the pupil;

- The impact the information has on the planned teaching and learning;

- The contribution assessment makes to cognition, learning and development.

Effective assessment is integral to the provision of cognitively challenging learning experiences. With careful and intentional planning, we can assess cognitive challenge and its impact, not only for the more able pupils, but for all pupils. Assessments are used to measure the starting point, the learning progression, and the impact of provision. When working with more able pupils, in cognitively challenging learning environments, the aim is to extend assessment practices to include assessment of higher-order, complex and abstract thinking.

When used well, assessment provides the teacher with a detailed understanding of the pupils’ starting points, what they know, what they need to know and what they have the potential to do with their learning. The teacher can then plan an engaging and exciting learning journey which provides more able pupils with the cognitive challenge they need, without creating cognitive overload.

The Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) has joined with others to recognise the importance of cognitive science to inform interventions and classroom practice. Spaced learning, interleaving, retrieval practice, strategies to manage cognitive load and dual coding all support cognitive development – but are dependent on effective assessment practices which guide the teaching and learning. The best assessment methods are those that integrate fully within curriculum teaching and learning.

Assessment and classroom management

It is important to place the learner at the centre of any curriculum plan, classroom organisation and pedagogical practice. Initially the teacher must understand the pupils’ strengths and weaknesses, together with the skills and knowledge they possess, before engaging in new learning. This understanding facilitates curriculum planning and classroom management, which have been recognised as essential elements of cognitively challenging learning. Often, learning time is lost through additional testing and data collection, but when working in cognitively challenging environments, planned learning should be structured to include assessment points within the learning rather than devising separate assessment exercises.

When assessing cognitively challenging learning, pupils need opportunities to demonstrate their abilities using analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. They must also show how they use their existing knowledge in new, creative, or complex ways, so questions might include opportunities to distinguish between fact and opinion, to compare, or describe differences. The problems may have multiple solutions or alternative methodologies. Alternatively, pupils may have to extend learning by combining information shared with the class and then adding new perspectives to develop ideas.

Assessing cognitively challenging learning will also include measures of pupils’ abilities to think strategically and extend their thinking. Strategic thinking requires pupils to reason, plan, and sequence as they make decisions about the steps needed to solve problems, and assessment should measure this ability to make decisions, explain solutions, justify their methods, and obtain meaningful answers. Assessments which demonstrate extended thinking will include investigations, research, problem solving, and applications to the real world. Pupils’ abilities to extend their thinking can be observed through problems with multiple conditions, a range of sources, or those drawn from a variety of learning areas. These problems will take pupils beyond classroom routines and previously observed problems. Assessment at this level does not depend on a separate assessment task, but teaching and learning can be reviewed and evaluated within the learning process itself.

Assessment in language-rich learning environments

Language-rich learning environments support cognitive challenge, high-order thinking and deep learning for more able pupils. It is therefore inevitable that language, questioning and dialogic discourse are key elements of formative assessment. They allow the teacher to assess learning in the moment and adjust the course of learning to adapt to the needs of the pupils.

Assessment in the moment, utilising effective questions and dialogic discourse, does not happen by accident, but is planned into the learning. When planning a lesson, the big ideas and essential questions which will expose, extend and deepen the learning are central to the planning and assessment. When posing the planned questions or creating opportunities for discourse, pupils need time to formulate their ideas and think before discussing the responses and extending learning with their own questions and ideas.

Within the language-rich classroom where an understanding of assessment is shared with pupils, the ownership of learning can be passed to them. The teacher will introduce the theory, necessary linguistic skills, and technical language, using these to model good questions and questioning techniques. More able pupils will develop their own oracy, language and questioning techniques, and then develop them together. Through regular practice and good classroom routines, pupils gain the confidence and skills to ask ‘big questions’ themselves and engage in dialogue. At this point, discussion and questioning becomes an effective mode of ongoing assessment. As pupils explain their thinking, misconceptions or gaps in knowledge will be exposed, allowing the teacher to assess, support learning, and encourage deeper thinking.

Priorities for effective assessment

Within the classroom, the teacher needs to use assessment:

- To understand what the pupils know already;

- To promote and sustain cognitive challenge and progression:

- To measure the impact of both the teaching and the learning;

- To adapt practice in a timely manner;

- To support, extend and enhance learning;

- To examine how effectively the knowledge is used in new, varied and complex contexts.

Assessment has the potential to support pupils as learners as they will:

- Understand the nature and purpose of activities so that they can benefit from them;

- Appreciate the demands of learning;

- Engage in the learning journey;

- Develop their own cognitive skills and learning attributes;

- Take action to improve themselves;

- Take ownership of learning;

- Become increasingly autonomous and self-regulating.

Assessment is not a separate part of teaching and learning, but should be planned within the teaching. Assessment should not distract pupils from learning, and learning should not be framed to meet assessment criteria. Assessment is not about data gathering and organisational checks, but it should lead to enriched learning and refined practice with teachers and pupils working together to achieve an exciting learning environment.

What next?

This year, NACE is focusing on exploring effective assessment practices within Challenge Award-accredited schools. We hope that many schools will participate in this project, to provide evidence and share examples of effective assessment: what works, how, and why? By sharing our expertise with others we can move the conversation about assessment forwards and provide exciting and engaging learning for our pupils. To find out more or to express your school’s interest in contributing to this initiative, please contact communications@nace.co.uk

References

- Education Endowment Foundation (2021), Cognitive science approaches in the classroom (a review of the evidence)

- Rimfield. K, et.al. (2019), Teacher assessment during compulsory education are as reliable, stable, and heritable as standardized test scores. The Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 60(12) (1278-1288)

Read more:

Tags:

assessment

cognitive challenge

feedback

myths and misconceptions

oracy

progression

questioning

research

Permalink

| Comments (2)

|

|

Posted By Chris Yapp,

08 September 2020

|

Dr Chris Yapp, NACE Patron

This past month has been marked for me by the death of two major influencers on my thinking and life over 30 years. Lord Harry Renwick died from COVID-related complications and Sir Ken Robinson from cancer.

Harry was a past Chairman of the British Dyslexia Association, a lifelong passion, and an early supporter of the societal and economic good that computing could bring. He was generous to me with his time and opened many doors in parliament, but also outside. Importantly, he led me to the work of Thomas G West. I still have a signed copy of “In the Mind’s Eye” (first edition) on my shelf. I have been delighted to discover that there is a new edition now available.

Tom’s work in the USA on visual giftedness ought to be as influential and well-known as Howard Gardner’s books. His evidence on visual thinking and creativity in science and mathematics made sense of various anecdotes I had collected over the years but could not make coherent.

That is where the link with Sir Ken Robinson comes in. I did not know him well; we met five times over around 15 years, the last time being a decade ago. I would like to add my tribute to him and address a criticism of his thinking that has been raised in many of the otherwise warm obituaries and tributes to a life well-lived.

I followed Ken Robinson speaking at a conference around 1995. My advice to anyone who would listen was, “Do not accept an invitation to speak after Ken Robinson.” At that time the usual reaction was, “Who is he?” I don’t think there is anyone connected with education now – since his famous TED lecture "Do schools kill creativity?" – who would ask that. He was a brilliant communicator, of that there is no doubt, but I want to pay tribute to him outside the podium.

He was as engaging and fun away from the speaker platform as he was on it. He was an avid networker who loved to connect people who he thought would find each other stimulating company. His network of contacts was truly global. An educator I much admire, Richard Gerver, who was mentored by Sir Ken, has written a very personal tribute here. It is well worth a read.

1999 was the 40th anniversary of a famous speech by C P Snow, “The Two Cultures”. I gave a talk at a conference on the “Renaissance of Learning”. After leaving the platform Ken came up to me. He wanted to talk about one slide. I had argued that there was a false dichotomy in education policy in the UK but also internationally, that the arts were creative, and engineering was a discipline. Drawing on C P Snow’s ideas I suggested that you could not be a great engineer if you were not creative or a good artist without discipline. I had given examples of “seeing” the mathematics as an aesthetic experience. Ken wanted the reference, which was to Tom West’s work. His advice to me was simple: “Keep saying it, one day they’ll listen.”

Over the years I have been contacted by people around the world on email or social media, where the opening line has been: “I met Sir Ken at a conference and he suggested I look you up. He said you’d been thinking about this for years.”

None of the exchanges that followed have ever been with timewasters. I think the last was around five years ago, five years after we last spoke. He used his global celebrity status to bring like minds together. He was far humbler and more cautious than the public speaker image may project.

The criticism I want to address is this: that he did not appreciate creativity in science and maths. In my opinion, for what it’s worth, he avoided the celebrity status trap of pontificating on things that he had little mastery of. I think he was right to do so.

Of course, he was a passionate about the arts, but he had a genuine interest in creativity in all its forms. The people he pointed in my direction were engaging with his ideas in physics, chemistry, mathematics and many more disciplines.

He will be much missed as an inspiration, but he has left a legacy of a life lived well.

If you are passionate about creativity in education, I can pay no finer tribute to Sir Ken than his own words to me: “Keep saying it, one day they’ll listen.”

About the author

NACE patron Dr Chris Yapp is an independent consultant specialising in innovation and future thinking. He has 30 years’ experience in the ICT industry, with a specialisation in the strategic impact of ICT on the public sector, creative industries, digital inclusion and social enterprises. With a longstanding interest in the future of education, he has written and lectured extensively on the challenges of personalised learning, lifelong learning, educational transformation and the knowledge economy.

Join Chris at this year’s NACE Leadership Conference (16-20 November) for a session exploring the use of learning technologies to extend and enrich learning.

View the conference programme.

Tags:

arts

collaboration

creativity

critical thinking

curriculum

math

myths and misconceptions

science

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Neil Jones,

22 January 2020

|

Neil Jones, Lead Practitioner for More Able Students at Impington Village College, shares key findings from the school’s focus on understanding the gender gap and moving beyond common stereotypes to develop more effective forms of support.

In common with many schools in England, our school identifies a gap in attainment between boys and girls at GCSE. In my role as Lead Practitioner for More Able Students, I had also noted an even larger gap, between boys and girls identified by teachers as having particularly high academic ability or talent in foundation subjects. It seemed there might have been a perception that girls (as a group) simply outperform boys (as a group). As a result, one of our strategic priorities for 2018-19 was that “all students make accelerated progress, with a particular focus on disadvantaged students and boys”.

We established a working group to investigate the causes of the attainment gap, whether anything was happening (or not happening) in classrooms to cause or sustain this gap, and what we could realistically do to address this. Our investigation aimed to build on previous work and existing practice, drawing on the insight and support of the middle leaders who make up our professional learning group, while fully engaging all teachers.

Phase 1: developing our thinking

The working group developed an online questionnaire to gather colleagues’ perceptions on the gender attainment and engagement gap. This included the 15 “barriers to boys’ learning” outlined in Gary Wilson’s influential book Breaking Through Barriers to Boys’ Achievement: Developing a Caring Masculinity (2013). It also contained a ‘pre-mortem’ question: “Imagine we innovated a whole range of things to improve boys' engagement and progress... and it was a spectacular failure. Write down examples of what we got wrong, and the impacts.” This open approach led to heated and productive debate, with a high response rate and a wide range of opinions and concerns expressed.

With suggestions from teachers across the school, we compiled a reading list around the gender gap (see below for examples), aiming to identify core themes and patterns. The key findings from our reading were that:

- In the UK, there has been a 9% gap in achievement between girls and boys since at least 2005; prior to that a gap was in evidence at O-Level and the 11+ exam.

- This gap is the same in many developed countries, but the narrative is different. In France, for example, the gap causes less consternation.

- Historically, almost all cultures have bemoaned adolescent boys’ “idleness” and their “ideal of effortless achievement”.

- The gap narrows in late adolescence and, internationally, by the age of 30 males have outstripped females in terms of their level of education and training, and earnings.

- Gender is an unstable indicator of individual student’s attainment and engagement: not all boys are underachieving, and not all girls are achieving.

- Gender-based approaches to teaching and learning are too often gimmicky, distracting and have no discernible effect on achievement. Learning has always been difficult; engagement comes from excellent subject knowledge of the teacher, supportive monitoring of understanding and confidence between teacher and learner.

Members of the working group visited several other schools, including one investigating boys who were following or bucking the trend of underachievement, and two using one-to-one mentoring to support underachieving students.

Phase 2: interventions

We asked the Director of Progress to share lists of students whose reports showed they were making both less progress and less effort than required. While this selection was gender-blind, the lists were, unsurprisingly, dominated by boys.

We then ran two six-week trials concurrently: a series of one-to-one 20-minute mentoring sessions with Year 8 students and a series of small-group, hour-long mentoring discussions with Year 10 students. The working group consulted during this process and fed back on what we judged was effective or otherwise, from our perspective and the students’.

Phase 3: lessons learned

We learned, crucially, that we mustn’t and can’t reduce our response to identity politics; what we can do is focus on teaching effectively and caring well.

Impact on teaching

The first impact on effective teaching is that our already tailored CPD will continue to focus on quality-first teaching. Members of the working group led well-received sessions scotching myths about the need for “boy-friendly” approaches such as competitions, kinaesthetic tasks, novelty/technology, befriending the “alpha” male, banter/humour, peer-to-peer teaching, negotiation, single-sex classes or male teachers.

What is proven to work instead, since time immemorial, is excellent teacher subject knowledge, firm but fair behaviour management and high-quality feedback – all of which are in place through our school’s existing assessment, accountability and quality management systems.

Impact on pastoral support

The second impact, on pastoral care, is that we understood that our underachieving students are, overwhelmingly but not exclusively, male; lack confidence; are therefore risk-averse academically; do not feel listened to; do not talk enough in order to explore their goals; cannot therefore link their learning meaningfully to their lives; feel lonely.

While Year 8 students responded quite well to one-to-one interventions, they were not yet mature enough to reflect very usefully on their experience. The two small groups of Year 10 students, however, were eager to talk, reflect and offer solidarity in encouraging ways. Insights from participants included:

- “We work hard for the teachers who like us.”

- “Extended day is pointless.”

- “If we’re put in intervention, no one explains why.’”

- “Interventions make me feel sh*t.”

- “You need confidence to be motivated.”

- “Some of our targets are genuinely too high.”

- “It feels like the school is just after the grades.”

- “If you share how you really feel with your mates it will all crumble.”

Phase 4: ongoing provision and evaluation

As of September 2019, we are running fortnightly after-school mentoring sessions for small groups of Year 11 students identified as being below target in progress and effort (chosen gender blind – 75% male, 25% female). These mentoring sessions run as an option for students, alongside two compulsory interventions for a much larger cohort of Year 11s. The first of these is an extended day, where students can revise together in the school library and focus on their own defined areas of study. The second is a series of extra lessons delivered at the end of the school day.

Keeping mentoring as an option for students (and their parents) seems to give them more sense of agency and responsibility. Numbers participating can fluctuate from week to week, but those participating are very positive. Many of the conversations involve making priorities and keeping things in perspective, and we encourage students to come up with their own solutions.

While it may be impossible to quantify the precise impact of this intervention with more able students, several students did better in their mocks than predicted, and more in line with their aspirational targets. Several parents, too, have been in touch to say that they find it makes a difference to their child’s attitude to learning. Goals post-16 are more defined. My overall hope for the programme is rather like Dr Johnson’s hope for literature: to help these young people find ways “better to enjoy life or, at least, endure it.” We will continue to monitor the programme’s popularity with students and its effectiveness.

Our approach frames underachievement as an issue requiring a further level of pastoral intervention, aimed at developing good habits of mind, a sense of purpose and the confidence these things bring. We hope these sessions will build solidarity between mentors and mentees, mentees and class teachers, and between the young people themselves. This will be vital if underachieving students are to reframe study and school life as opportunities to become excited about their aspirations and aims in life. Importantly, this intervention does not create gimmicky, evidence-free busywork for the teaching body, neither does it discriminate unfairly against girls.

Key takeaways:

- The attainment gap between boys and girls of this age is perennial. The work we do in schools can only go some of the way to address it, so concentrate on what is in your control: teaching well and caring well.

- Excellent teaching is what it always has been: that which allows students, male and female, to think. Learning is what it always has been: necessary, sometimes exciting, sometimes hard and distasteful. That goes for all of us, male and female.

- That said, all children need to develop positive habits of mind to stay motivated and happy enough that their actions have meaning. There will be challenges to this, different between time and time and community and community. To work out what these challenges are, and how to address them intelligently, use a wide range of data to ask meaningful questions.

- Loneliness and a lack of discussion about aims and habits are main drivers of underachievement and can quickly erode wellbeing. Boys as a group appear to feel these deficits more keenly than girls as a group (but not exclusively). We are in loco parentis and need to prioritise time and space for students who don’t do so at home to explore and examine how to develop successfully, in ways that are personal to them.

- Use your colleagues’ professional expertise and nous and encourage them to engage in contextual reading. It is alarming at the present time – perhaps encouraged by the instantaneity of the Twittersphere – how much change can be reactive and ignore lessons from the history of education policy. Before initiating any major or contentious change, aim to run it by as many colleagues as possible and get a pre-mortem. In our experience, colleagues’ insights, suggestions and misgivings all played a crucial role in preventing us making major mistakes.

Recommended reading:

- UNESCO 2019 Gender Review: https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/2019genderreport

- Gender and Education Association: www.genderandeducation.com

- Gender issues in schools: what works to improve achievement for boys and girls – DCSF 2009

- Gary Wilson, Breaking Through Barriers to Boys’ Achievement: Developing a Caring Masculinity (2013)

- Matt Pinkett and Mark Roberts, Boys Don’t Try? Rethinking Masculinity in Schools (2019) - review

Before you buy… For discounts of up to 30% from a range of education publishers, view the list of current NACE member offers (login required).

Share a review… Have you read a good book lately with relevance to provision for more able learners? Share it with the NACE community by submitting a review.

This blog post is based on a case study originally published in the SSAT journal Leading Change: The Leading Edge Network Magazine, Innovation Grants Special Edition 2018-2019, LC22 (Autumn 2019)

Tags:

gender

mentoring

myths and misconceptions

research

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Hilary Lowe,

11 December 2019

Updated: 03 December 2019

|

NACE Education Adviser Hilary Lowe goes in search of the perfectly pitched challenge...

Building on NACE’s professional development and research activities, we continue to explore and refine the concept of ‘challenge’ in teaching and learning for high achievement – the central tenet of much of our work and the heart of provision for very able learners.

What do we mean by challenge?

The notion of challenge is multi-faceted and goes further than designing individual learning and assessment tasks. It merits a subheading which makes it clear what we mean. As a provisional and necessarily evolving definition:

“Challenge leads to deep and wide learning at an optimal level of understanding and capability. It encompasses appropriate learning activities but is more than that. Its other facets include, for example: the learning environment, the language of classroom interactions, and learning resources, together with the skills and attributes which the learner needs to engage with challenging learning encounters. These encounters may take place both within and beyond the classroom.”

Some of these building blocks coincide with pedagogical approaches and theoretical perspectives which enable challenging learning for a wide group of learners. It is important therefore that we also interrogate these perspectives and adapt related classroom practices to ensure relevance and application for the most able learners.

Our work on challenge in teaching and learning is part of a wider campaign that will also explore and promote the importance of a curriculum model which offers sufficient opportunity and challenge for more able learners.

Below, we focus on the design and delivery of challenging tasks and activities in the classroom which are likely to enable more able learners to achieve highly and to engage in healthy struggle.

Pitching it right: keep the challenge one step ahead

If teaching for challenge is providing difficult work that causes learners to think deeply and engage in healthy struggle, then when learners struggle just outside their comfort zone they will be likely to learn most. Low challenge with positive attitudes to learning and high-level skills and knowledge can generate boredom within a lesson, just as high challenge with poor learning attitudes and a low base of knowledge and skills can create anxiety. Getting the flow right, ensuring the level of challenge is constantly just beyond the learners’ level of skills and knowledge and their ability to engage will then create deeper learning and mastery.

By scaffolding work too much and for too long, and stealing the struggle from learners, we can undermine expectations and restrict the ranges of response that our learners could potentially develop unaided.

Implications for planning and teaching

What then are the implications for planning and for using every opportunity inside and outside the classroom to “raise the game”? Challenge should involve planned opportunities to move a learner to a higher level of achievement. This might therefore include planning for and finding opportunities in classroom interactions for:

- Tasks which encourage deeper and broader learning

- Use of higher-order and critical thinking processes

- Demanding concepts and content

- Abstract ideas

- Patterns, connections, synthesis

- Challenging texts

- Modelling and expecting precise technical and disciplinary language

- Taking account of faster rates of learning

- Questioning which promotes and elicits higher-order responses

When considering the level of challenge in your classroom, ask:

- Do you set high expectations which allow for the potential more able learners to show themselves?

- Have you reflected on prior learning and cognitive ability to inform your plans?

- Is your classroom organised to promote differentiation?

- Do you plan for a range of questions that will scaffold, support and challenge the full range of ability in your class?

- Can you recognise when learners are under- or over-challenged and adapt accordingly?

- Are you using examples of excellence to model?

- Will learners be challenged from the minute they enter?

Share with your learners your expert knowledge, your passion, your curiosity, your love of the subject and of learning. Have high expectations – and resist the urge to steal their struggle!

Challenge in the classroom: upcoming NACE CPD

New for 2020, NACE is running a series of one-day courses focusing on approaches to challenge and support more able learners in key curriculum areas. Led by subject experts, each course will explore research-informed approaches to create a learning environment of high challenge and aspiration, with practical strategies for challenge in each subject and key stage.

Details and booking:

An earlier version of this article was published in NACE Insight, the termly magazine for NACE members. Past editions are available here (login required).

Tags:

CPD

critical thinking

differentiation

feedback

mastery

myths and misconceptions

questioning

Permalink

| Comments (0)

|

|

Posted By Southend High School for Boys,

10 December 2019

|

Laura March, Hub Lead of the NACE R&D Hub at Southend High School for Boys, shares eight key issues discussed at the Hub’s inaugural meeting earlier this term.

Our inaugural NACE R&D Hub meeting was attended by colleagues from 12 schools, spanning a range of phases and subject areas. Ensuring the Hub meetings are focused on evidence and research allows us to respond to the masses of misinformation presented to us. A collaborative approach to understanding the needs of more able and talented (MAT) learners, and how to support them, enables colleagues to become more open and reflective in their discussions.

We started the meeting by sharing our own experience at Southend High School for Boys (SHSB), exploring our work towards gaining and maintaining the NACE Challenge Award over the last 15 years, and what strategies have had the biggest impact.

In the following discussion, it was interesting to explore what ‘differentiation’ means to different colleagues and key issues raised about what constitutes ‘good’ practice. It was also useful for colleagues from different fields – science, MFL, primary, physics, English and RE – to share approaches to developing writing skills, such as using ‘structure strips’, visualisers to model work, or tiered approaches to subject vocabulary. Finally, some questions were raised about communicating more able needs with parents; what should be included in the school’s more able policy; and how to monitor the impact of strategies on more able learners.

Here are eight key areas discussed during the meeting:

1. Strengthening monitoring and evaluation

This had been identified as an area for development at SHSB. MAT Coordinators and Subject Leaders are responsible for completing an audit to review their previous targets for more able learners and to outline opportunities, trips, competitions, resources and targets for the new academic year. This enables the MAT Lead to identify areas for pedagogical development so that targeted support can be put in place, as well as any budget requirements to purchase new resources.

2. Engaging with parents and carers

We shared the example of our parent support sheet. Not only are we bridging the gap between academic research and classroom practice, we aim to encourage a positive dialogue with parents by sharing the latest research on memory and strategies of how to stretch and challenge their sons and daughters at home. This has been very positive during parents’ evenings, with departments recommending extended reading; apps for effective revision such as Quizlet and Seneca; and You Tube videos for specific topics.

3. The zone of proximal development